|

|

|

|

|

|

| "Culture can be defined as those social practices [or discourses] whose prime aim is signification, i.e. the production of sense or making orders of 'sense' for the world we live in. Culture is the social level in which are produced those images of the world and definitions of reality which can be ideologically mobilized to legitimize the existing order of relations of domination and subordination between classes, races, and sexes." (Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Feminity, Feminisism, and Histories of Art, New York, 1988, p. 20) |

| "To understand the ideological double bindings that legitimize the discipline's operational protocols, it is necessary to attend to the fact that language is never transparent, neutral, or value-free. To employ a disciplinary language (from the jargons of formalism to those of semiology) is to enter into a composed and prefabricated world, a tapestry of ontological patterns. Often, an illusion of greatest freedom and idiolective bricolage masks precisely those sites of declamation that are most controlled. The observer in the disciplinary panopticon, while hidden and separated from the system of objects under observation, is himself in a prefabricated position or locus, captive in a device that delimits and defines what may be seen at all. Both seer and seen are components of this apparatus (Donald Preziosi, Art History: Meditations on a Coy Science, Yale, 1989)." |

A central premise of Post-Modern criticism is that we are constructed in the codes, discourses, and languages of our cultural contexts. These codes do not seem to be artificial to us but "natural", but this naturalness is an effect of the power of culture in defining us and the way we look at the world. Culture makes natural or, to use Pollock, "legitimize[s] the existing order of relations of domination and subordination between classes, races, and sexes." In reading Preziosi's quotation above, substitute "culture" for "discipline." Post-Modern criticism asks us to critically analyze the role of our educational and cultural institutions in constructing us.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth saw the rise of an important new institution in European culture: the public art museum. Museums in England (British Museum and National Gallery of Art), France (Louvre), Germany , Italy, and ultimately the United States played important roles in defining national identity. Carol Duncan in the following quotation from her book Civilizing Rituals strongly argues for the critical role these museums played:

| To control a museum means precisely to control the representation of a community and its highest values and truths. It is also the power to define the relative standing of individuals within that community. Those who are best prepared to perform its ritual --those who are most able to respond to its various cues-- are also those whose identities (social, sexual, racial, etc.) the museum ritual most fully confirms. It is precisely for this reason that museums and museum practices can become objects of fierce struggle and impassioned debate. What we see and do not see in art museums --and on what terms and by whose authority we do or do not see it-- is closely linked to larger questions about who constitutes the community and who defines its identity [pp. 8-9]. |

This is an idea that is echoed in the following statement by Donald Preziosi:

| The museum is one of the most brilliant and powerful genres of modern fiction, sharing with other forms of ideological practice --religion, science, entertainment, the academic disciplines-- a variety of methods for the production and factualization of knowledge and its sociopolitical consequences. Since its invention in late eighteenth-century Europe as one of the premier epistemological technologies of the Enlightenment, the museum has been central to the social, ethical, and political formation of the citizenry of modernizing nation-states. At the same time, museological practices have played a fundamental role in fabricating, maintaining, and disseminating many of the essentialist and historicist fictions which make up the social realities of the modern world ("Collecting / Museums," in Critical Terms for Art History, Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff eds, Chicago, 1996, p. 281). |

As a way of gaining an understanding the role the art museum plays in the forming of ideology I want to consider a late nineteenth century painting by James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot entitled London Visitors (see above). I think implicit in this image are the social and cultural functions of the art museum in late 19th century England. The nineteenth century British critic William Hazlitt articulates the primary objective of the National Gallery of Art in terms that strikingly resonate with Tissot's painting:

| It is a cure (for the time at least) for low-thoughted cares and uneasy passions. We are abstracted to another sphere: we breathe empyrean air; we enter into the minds of Raphael, of Titian, of Poussin, of the Caracci, and look at nature with their eyes; we live in time past, and seem identified with the permanent forms of things. The business of the world at large, and even its pleasures, appear like a vanity and an impertinence. What signify the hubbub, the shifting scenery, the fantoccini figures, the folly, the idle fashions without, when compared with the solitude, the silence, the speaking looks, the unfading forms within? Here is the mind's true home. The contemplation of truth and beauty is the proper object for which we were created, which calls forth the most intense desires of the soul, and of which it never tires [as quoted in Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums, London, 1995, p. 15]. |

Tissot's painting has the semblance of a random and neutral glimpse of the world. Compare the point of view in Tissot's painting to the accompanying image:

|

|

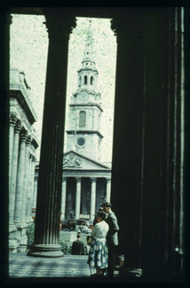

The authenticity of this vision is emphasized by the fact that we can identify the actual spot depicted in the painting. The people are standing in the Greek Revival portico of the National Gallery of Art in London:

Through the columns we can see the church

of St. Martin's in the Fields designed by Christopher Wren in

the early eighteenth century. Both the facades of the church and

the National Gallery are directly tied to the tradition of Classical

architecture inherited from Greek and Roman art. The facade of

the Temple of the Pantheon constructed by the Emperor Hadrian

at the beginning of the 2nd century A.D. exemplifies this traditional

temple facade:

Through the columns we can see the church

of St. Martin's in the Fields designed by Christopher Wren in

the early eighteenth century. Both the facades of the church and

the National Gallery are directly tied to the tradition of Classical

architecture inherited from Greek and Roman art. The facade of

the Temple of the Pantheon constructed by the Emperor Hadrian

at the beginning of the 2nd century A.D. exemplifies this traditional

temple facade:

Think of your own experience of facades like this. Where do you find them? How do they make you feel? What are their purposes?

To the right of the painting would be Trafalgar Square in the center of which is a monument dedicated to Lord Nelson, an Admiral in the British navy who was killed during his victory at the Battle of Trafalgar:

The Nelson Monument is formed by a statue of Lord Nelson atop a Corinthian Column derived from Greek and Roman architecture. The form of this monument is directly tied to a form of Triumphal Monument that can be traced back to Roman art best exemplified by the Column of Trajan constructed in the early 2nd century A.D. in Rome:

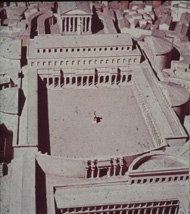

It is important to see a public space like Trafalgar Square within a tradition of comparable spaces in city planning. For example, the Column of Trajan was a part of a larger complex, the Forum of Trajan. It was traditional in Roman city planning to have at the center a large public space within which major formal public buildings would be placed. These fora in the Roman city served to give visual form to the dominant Roman values and the authority of the state. Although no longer extant, the Forum of Trajan can be reconstructed:

|

|

It is worthwhile to identify the different monuments included in the Forum of Trajan. To enter the forum one would go through a Triumphal Arch dedicated to Trajan. You would then be in the large forecourt with an Equestrian statue of Trajan in the center. This forecourt is terminated by a large building called the Basilica Ulpia. The Basilica type was a very defined type of building in Roman architecture. Most Roman cities would have a Basilica. One of its primary functions would be as a law court. Beyond the Basilica, there were two libraries --one Greek and the other Latin. These libraries flank the Column of Trajan. The complex was terminated by the Temple of the Divine Trajan, dedicated by his successor the Emperor Trajan. Note the different institutions included in the Forum and consider their symbolic relationship to authority of the Emperor Trajan and the Roman Empire. Compare this to Trafalgar Square. Also consider other major public spaces in our cities. For example, anyone familiar with Empire Plaza in Albany, compare it to the Forum of Trajan and Trafalgar Square. Also consider the parallels to the Mall in Washington, D.C. Remember that the National Gallery of Art is a part of the Mall. Consider the implications of this type of planning in Western architecture. As a tangent here consider the implications of the idea of "Empire." Remember central to the Roman concept of power is their notion of Empire. Also remember that Tissot painted his painting at the height of the British Empire.

Studies of the painting have shown that the dress of the boys depicted in the painting can be identified as being that of Christ's Hospital School in suburban Hertford. I think closer examination of the painting will reveal that this semblance of a transparent and objective vision is illusory, and that Tissot in constructing this painting is making an assertive statement of British ideologies of the period, their attitude to the world, and their position in history. As a journal entry, I would like you to identify as many of the different institutions that are directly or implicitly depicted in the painting. From your general awareness of the position of Britain and its empire in the world during the nineteenth century, try to articulate how these various institutions are related to define a British ideology.

Obviously one of the institutions present in the painting is the art museum and the role art plays in the social, cultural, and political life in the West. As a way of giving more focus to our discussion respond to the following questions. Relate your experience of seeing this painting to your own experience of going to an art museum. What generalizations can you make about the locations of art museums? What relationships do you understand to be between the art museum and the surrounding buildings and/or spaces? What purposes does a formal entrance like the one shown in the painting play? What do or don't you expect to see in art museum? Be as specific as possible. Anyone who has been to either the National Gallery in London or the National Gallery in Washington list what you saw and didn't see there. I encourage you to make a virtual visit to these museums on-line: National Gallery of Art in London and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. What criteria can you give for the inclusions and exclusions? Try to define the logic or criteria used in organizing an art museum. Describe your feelings in entering an art museum. What does your experience of visiting an art museum remind you of? Generally, art museums are defined in our society as cultural institutions. Identify other types of cultural institutions in our society. How would you define the purposes of cultural institutions in our society?

Addendum:

In the 1990's the National Gallery was expanded by the opening of the Sainsbury Wing. The design of this addition became the focus of much public debate. In the 1980's, the design below was approved by the government:

This design was subsequently withdrawn as a reaction to public criticism particularly aroused by Prince Charles. The final form was designed by Robert Venturi:

The contrast between the two designs can be used to illustrate the shift from Modern to Post-Modern architecture. Rather than drawing a contrast between the traditional Classical facade and the Modern building, Venturi's design attempts to be much more in harmony with the original building. This can also be seen in the interior of the building. Notice how the monumental staircase marking the entrance to the new wing echoes the effect of the facade shown in the Tissot painting:

Consider even the choice of the fifteenth century Florentine painting by Botticini of the Assumption of the Virgin that is hung on the wall at the top of the staircase.