The Fall in the Art of Hans Baldung

Excerpts from Joseph Koerner, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art

p. 293: In Baldung's Death and the Woman from about 1518-19, now in Basel, everything seems to open to our gaze. The woman's garments separate to reveal her naked body. Her white flesh stands out against the dark background and brownish cadaver, drawing our eye toward her. We cannot tell whether she actively reveals herself (she holds the ends of the white cloth at either side of her body) or whether, in trying to resist the corpse, she accidentally lets her garment fall. Perhaps she tries to hold them up, to keep herself covered despite the assault. The gesture of her arms, however, exposes her body even more, making her more vulnerable to both the groping hands of Death and the open eyes of the beholder. Baldung captures a particular instant in this cruel drama of exposure: the falling garments form a V whose apex is also the apex of the V of her groin. These diagonals organize the picture. The upper edge of the cloth at the right carries down into the orthogonal on the ground plane at the lower left, while from the left a diagonal passes from the woman's right upper arm, through the edge of her falling garment, and along Death's exposed left shin. These organizing lines are paralleled and strengthened by others, such as the line formed by the bough of the tree or the diagonal formed by the woman's right forearm. Baldung thus focuses his painting matrix of shapes around the pubic triangle, where the cloth is just about to part and reveal the woman's "full" sexuality.

The painting arrests us at the instant just before this revelation, at a visualized "point" of anticipation....In Death and the Woman, the instant of nakedness coincides with another event that we also see arrested before completion. Death's teeth are poised to bite its victim but have not yet grazed her flesh. The sense is that the moment Death closes its teeth, the woman's garment will fall open. The painting thus situates us at the moment when Eros and Thanatos merge: sex, expressed in the woman's concealed/revealed flesh and in the corpse's act (for its bite is also a lipless kiss), becomes identical to death, expressed in the garments funeral shroud and in the bite as putrefaction. And all around, opening up with the woman's clothes, the beholder's eyes, and the jaws of Death, are yawning graves, cemetery versions of the bridal bed.

The woman's striptease, imagined as both willing and unwilling, and arrested at the point where "more" will be revealed, engages and sustains the viewer's open eyes. She becomes an object of a specifically male desire, a bait deployed to trap the phallic gaze; her function is to elicit this gaze and to interpellate it as reprehensible. Her tears, cleverly rendered by the artist as highlights upon white flesh, might register her own status as experiencing subject, yet the overall plot of the picture, the way it addresses the viewer /p. 294 and fashions its controlling allusions, overlooks her plight. Her efforts, as they are staged by Baldung, collapse two moments. At the same time as she turns toward her attacker as if desiring him despite herself, her tears express a suffering consequent on that desire, a suffering born from the contradiction between will and knowing. Her very overdeterminedness --she at once is an object of desire and herself dramatizes desire's essential ambivalence--also informs the curiously irrational shape of the funeral shroud. The white cloth (or rather cloths, for the shroud seems to be made of two separate pieces) could never have dressed the woman but function only to suggest that she is undressed. Thus drawn to the woman's body, the eye can travel along its curved shape to her face, where warmth of life has collected in the pink blush that color her otherwise cadaverously white body. At this point at which the desiring phallic gaze apprehends a touch of life, Death's teeth meet the woman's flesh.

Nothing in this painting is quite as sensual, in the sense of strongly felt, as this meeting of opposites, where the soft, warm, and living flesh of the woman meets the hard, cold teeth of Death. Surely the corpse's gesture is linked to the position of the picture's implied male beholder: where he can only look, the cadaver can touch and taste. This grotesque tableau of almost fulfilled desire links sexuality to repulsion with the experience of the painting. Death is the viewer's doppelgänger within the painted world. Nibbling at the bait, it expresses male erotic desire at the very instant it annihilates that desire and therefore mortifies the flesh through the power of horror inherent in its macabre form....

/p. 295: In Death and the Woman, the corpse rapes the

woman from behind, recalling those surprise attacks in such macabre scenes

as the Three Living and the Three Dead, or Baldung's own Death overtaking

a Knight. More important, however, Baldung positions the corpse in Death

and the Woman so that its form echoes the figure of Adam as a he appears

in certain of the artist's depictionss of the fall of man. In

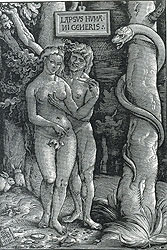

Baldung's 1519 woodcut Fall, a work exactly contemporary with the

Basel panel, Adam approaches Eve from behind, trapping her in a subtle and

erotically charged embrace. Grasping her shoulder with one hand while covering

--or tickling-- her groin with a leaf held in the other, his right foot planted

before hers, Adam does not so much restrain Eve as resist or impede her progress.

Eve, in turn, appears to draw away from Adam; reacting to his touch, she assumes

a posture quite similar to that of the woman in the Basel panel. Even

In

Baldung's 1519 woodcut Fall, a work exactly contemporary with the

Basel panel, Adam approaches Eve from behind, trapping her in a subtle and

erotically charged embrace. Grasping her shoulder with one hand while covering

--or tickling-- her groin with a leaf held in the other, his right foot planted

before hers, Adam does not so much restrain Eve as resist or impede her progress.

Eve, in turn, appears to draw away from Adam; reacting to his touch, she assumes

a posture quite similar to that of the woman in the Basel panel. Even  more suggestive

are the parallels between Death and the Woman and Baldung's later Adam

and Eve from 1531-33, now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Lugano.

Again Adam approaches Eve from behind, this time assuming a stance in many

details identical to that of the corpse in the Basel painting....

more suggestive

are the parallels between Death and the Woman and Baldung's later Adam

and Eve from 1531-33, now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Lugano.

Again Adam approaches Eve from behind, this time assuming a stance in many

details identical to that of the corpse in the Basel painting....

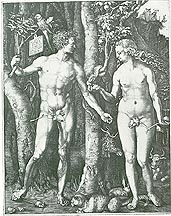

In the Lugano Adam and Eve, a naked woman again stands exposed to our gaze. This appeal to the eye is deliberate: Adam seems to hold or offer Eve up to our sight. He rests his left hand gently on her hip, as if simultaneously to touch and to frame the contours of her body. His right hand, too, is careful not to cover any curve of the breast it cups. Within this painting, touching is secondary to seeing. The transparent veil covering Eve's genitals, held in place by Adam's hand ( which covers Adam's genitals just as the cloth /p.298: covers the corpse's groin in the Basel panel) conceals nothing. Rather, like the shroud in Death and the Woman, the gossamer wrapped about Eve's hips only draws attention to her sexuality. We find ourselves looking through the veil, and like or not, our gaze becomes a trespass. There is, of course, something willfully artificial about Baldung's placement of this transparent shroud within Eden's natural paradise, as if the Fall occasioned not merely the fig leaf, but also the already festishized paraphernalia of sexual concealment. Made of costly imported fabric, such a weave would, at the very least, have suggested an attitude of vanitas. Baldung's contemporary viewers, moreover, would have recognized in the veil an attribute of prostitutes, who in this period were often forced to wear such a garment as a badge of their profession.

By thus outfitting his Eve with the marks of a fallen sexuality,

Baldung invites, or even forces, his male viewers to experience their own voyeuristic

desire, mirroring the worst in them in the lascivious gaze of Adam. The word

"mirror" is, I believe appropriate, for in this painting one has the sense

that Adam not only gazes out of the painted space toward us but appears to

be regarding himself in a mirror, fascinated by the sight of his own flesh

making contact with Eve's body. Thinking about the painting in this way illuminates

Adam's sidelong glance. He wants both to touch Eve and to observe himself touching

her. Thus he leans his face toward her, resting cheek against cheek,  while

at the same time glancing off to the right to watch his gesture mirrored. That

is why he takes care to handle her body so that everything erotic remains exposed

even as it appears to be touched by him. We, of course, stand where this notional

mirror would be. Adam's leering eye interpellates the viewer in its gaze, making

him an accomplice to fallen sexuality. Such

an arrangement is already present in Baldung's earliest depiction of the Fall

of Man,

while

at the same time glancing off to the right to watch his gesture mirrored. That

is why he takes care to handle her body so that everything erotic remains exposed

even as it appears to be touched by him. We, of course, stand where this notional

mirror would be. Adam's leering eye interpellates the viewer in its gaze, making

him an accomplice to fallen sexuality. Such

an arrangement is already present in Baldung's earliest depiction of the Fall

of Man,  the

chiaroscuro woodcut date 1511, in which Adam, gazing with Eve out at the viewer,

plucks a fruit from the forbidden tree with his right hand, while with his

left he cups Eve's breast from below. And it is made even more explicit in

a lost work by Baldung, known from a contour drawing now in Coburg, in which

Eve gazes out at the viewer while Adam reaches down to finger her genitals

between her crossed legs. James Marrow, following E.M. Vetter, has remarked

that Baldung is the first artist to represent the Fall as an overtly erotic

act. In the Eve of the Lugano Adam and Eve, with her see-through veil,

Baldung carries his intentions a step further. The Fall is now explicitly associated

with voyeurism, with fallen sexuality as perverted vision or scopophilia. As

such, any distance between original sin and the beholder's fallenness is annihilated.

Party to Adam's desires (if not to his actions), the male viewer recognizes

his true kinship with Adam. Thus are the sins of the fathers visited upon the

sons....

the

chiaroscuro woodcut date 1511, in which Adam, gazing with Eve out at the viewer,

plucks a fruit from the forbidden tree with his right hand, while with his

left he cups Eve's breast from below. And it is made even more explicit in

a lost work by Baldung, known from a contour drawing now in Coburg, in which

Eve gazes out at the viewer while Adam reaches down to finger her genitals

between her crossed legs. James Marrow, following E.M. Vetter, has remarked

that Baldung is the first artist to represent the Fall as an overtly erotic

act. In the Eve of the Lugano Adam and Eve, with her see-through veil,

Baldung carries his intentions a step further. The Fall is now explicitly associated

with voyeurism, with fallen sexuality as perverted vision or scopophilia. As

such, any distance between original sin and the beholder's fallenness is annihilated.

Party to Adam's desires (if not to his actions), the male viewer recognizes

his true kinship with Adam. Thus are the sins of the fathers visited upon the

sons....

/p. 302:

|

|

|

|

Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1507 (Prado) |

Baldung Grien, Adam and Eve,

1525 (Budapest) |

||

To appreciate the distance Baldung has traveled from his teacher's

representations of the prelapsarian Adam and Eve, we need only compare the

Budapest panels with Dürer's Prado Adam and Eve of

1507. As we recall, Baldung not only knew these twin panels from the period of his Nuremberg apprenticeship, but also produced a  faithful copy of them, elaborated by animals taken from Dürer's engraved Fall. Dürer's Adam and Eve panels provide the essential formal model for a number of /p. 303: secular works by Baldung.... Yet Baldung overturns the whole tone and message of his teacher's art. Dürer, in his Prado panels, labored to create delicate, youthful, and indeed innocent figures, improving on his construction of ideal beauty in the engraved Fall by naturalizing his figures' poses, freeing up their movements, and softening their contours. Baldung, in the Budapest Adam and Eve, contorts his nudes into deliberately artificial poses and thematizes that very "artifice" through the conceit of the now patently corrupt pair.

faithful copy of them, elaborated by animals taken from Dürer's engraved Fall. Dürer's Adam and Eve panels provide the essential formal model for a number of /p. 303: secular works by Baldung.... Yet Baldung overturns the whole tone and message of his teacher's art. Dürer, in his Prado panels, labored to create delicate, youthful, and indeed innocent figures, improving on his construction of ideal beauty in the engraved Fall by naturalizing his figures' poses, freeing up their movements, and softening their contours. Baldung, in the Budapest Adam and Eve, contorts his nudes into deliberately artificial poses and thematizes that very "artifice" through the conceit of the now patently corrupt pair.

Dürer's Prado Eve stands naked and unaware of our gaze, while a leafy branch "happens" to cover her genitals, meanwhile supporting a tablet with the artist's name and monogram. The link between this branch and the Dürer's self-denomination is perfectly fitting, for according to some medieval sources, the aprons that Adam and Eve sewed together from leaves after the Fall were the world's first art objects. In Dürer's, Eve's innocence (or what remains of its before she eats the fruit offered to her by the serpent) is expressed in candor with which she is exposed and concealed. For as contemporary theologians had it, "Blameless nudity...is that which Adam and Eve had before sing..nor were they confounded by that nudity. There was in them no motion of body deserving shame, nought to be hidden, since nothing in what they felt needed restraining." Baldung, on the other hand, reveals and dismantles the false artifice involved in the venerable artistic convention of concealed prelapsarian nakedness-- that is, the illusion, engineered by Dürer and subsumed under a notion of "decorum," that the covering leaves are there just by chance. Baldung demonstrates that human representation cannot pretend to be the purveyor of an unspoiled, prelapsarian innocence of vision. This "message" is instantiated in the way we, as beholders, interpret his images. To say, for example, that Eve's gesture in the Budapest panel is a deliberate, seductive, and erotic concealment of sexuality, or to interpret her as possessing a "knowing" look, is to betray our knowledge of sexuality and deception and therefore to admit our own fallenness. Whereas Dürer places his marks of authorship at precisely the place of recuperated, innocent modesty (the tablet hanging as if "naturally" from the covering branch), Baldung locates self within the domain of fallen self-consciousness, evident both within and before the painted image....

That Adam caused death to come into the world and that men and women became conscious of their nakedness only after the Fall are theological commonplace. What is interesting about Baldung's interpretations of the Fall, though, is not so much their content but the way they communicate this content. On one level, the "meaning" of the  Fall is expressed by images that invite the viewer to reenact, or at least to reflect, his own postlapsarian condition in the shape of his interpretation. Thus in the Lugano Adam and Eve, Adam stands behind Eve, mirroring our own, serves to expose us and /p. 305: reveal the fallenness of our gaze. But the mirror has other reflections on its surface.

Fall is expressed by images that invite the viewer to reenact, or at least to reflect, his own postlapsarian condition in the shape of his interpretation. Thus in the Lugano Adam and Eve, Adam stands behind Eve, mirroring our own, serves to expose us and /p. 305: reveal the fallenness of our gaze. But the mirror has other reflections on its surface.  The figure of Adam has itself been parodied by the animated corpse in another of Baldung's paintings. Although Baldung executed the Lugano panel over ten years after the Basel Death and the Woman, the two compositions realize consecutive moments in a single event. It is as if Adam, after fondling Eve from behind (the Lugano Adam and Eve) , turns to kiss her and, in that instant, becomes the emblem of his fall (the Basel panel). Gazing through Baldung's Adam and Eve to the macabre image of Death and the Woman,we see at once our kinship with Adam and, dimly, the effect of that kinship.

The figure of Adam has itself been parodied by the animated corpse in another of Baldung's paintings. Although Baldung executed the Lugano panel over ten years after the Basel Death and the Woman, the two compositions realize consecutive moments in a single event. It is as if Adam, after fondling Eve from behind (the Lugano Adam and Eve) , turns to kiss her and, in that instant, becomes the emblem of his fall (the Basel panel). Gazing through Baldung's Adam and Eve to the macabre image of Death and the Woman,we see at once our kinship with Adam and, dimly, the effect of that kinship.

Baldung's Images of Witches

Hans Baldung, Witches' Sabbath, 1510, chiaroscuro woodcut.

/p.329: Now the belief that women are more material and carnal than men, and therefore more prone to witchcraft, is hardly unique to Baldung. The Malleus spends a whole chapter on "Why It is That Women Are Chiefly Addicted to Evil Superstitions." And Geiler, in his 1508 Lenten sermons, recalls the truism that "if one burns one man, one probably burns ten women." These numbers are borne out in fact. It has been estimated that about 80 percent of the some 100,000 witches executed in Europe between 1400 and 1700 were women. This proportion was probably higher in the period before 1560; for as Norman Cohn puts it, "Until the great European witch-hunt literally bedevilled everything and everyone, the witch was almost by definition a woman." Baldung visualizes this terrible, seamless equation. He confirms the misogynist double fantasy that all witches are women and all women are potentially witches. And he does this through the spectacle of nude female bodies: bodies rendered in the figural style and linear idiom of Dürer's Apocalypse, but capable of gestures and postures far more energized, unruly, and potentially seductive than anything seen before in northern art. For us whose mental picture of witches is so determined by Baldung's formulation and its heirs, it is hard to imagine the impact the 1510 woodcut must have had on its original viewers. They must have felt their fantasies suddenly made real, and vindicated in their hate, they would have learned exactly what it was they sought to expose and destroy. Yet those familiar with the complex lore of the maleficium would also have noticed the devil missing from the scene. Searching for him, they would have found him too close by. Indeed he is, I shall argue, present as the image's implied beholder.

Depending on its audience, Baldung's chiarscuro woodcut can establish, confirm, and anatomize the male fantasy of the night witch. Although produced in a period and a city not especially prone to witch-hunting, its concrete vision of evil certainly derived from, and could lend support to, the work of the inquisitors and thus can be linked to the great massacres of later decades. My concern is more narrow than Baldung's place within the larger history of the witch-hunt, however. I seek to analyze what his images of witches say about their viewers and about the general character of Baldung's art....

Hans Baldung (shop), New Year's Sheet, 1514.

In a chiaroscuro drawing dated 1514, known from what may well be a workshop copy in the Albertina, Baldung concatenates three nude female bodies to form a triangular shape on the plane surface of the sheet. The women strike wild, energized poses, stretching and twisting their fleshy limbs and torsos in movements akin to an orgiastic dance --or , rather, akin to what polite society imagines an orgiastic dance to be. The exact purposes of their actions is left open, though most of their efforts focus on the somersaulting foreground woman, who, assisted by her companions, peers out at us from between her legs. The nudes thus form the machinery or frame for this inverted gaze. Like the look of Cusanus's omnivoyant icon of God, the tops-turvy woman's eyes follow us wherever we go, interpellating us constantly as the picture's center.

In a chapter entitled "Of the Continuing of the Torture," the Malleus warns inquisitors of the hypnotic power of a witch's gaze: " We know from experience that some witches when detained in prison, have importunately begged their gaolers to grant them this one thing, that they should be allowed to look at the Judge before he looks at them." For by "getting the first sight" of the inquisitor, they can rob him of his judgment. Witches, therefore, "should be led backward into the presence" of the inquisitor. And because they sometimes conceal charms and potions in their clothing, they should also have been "stripped by honest women of good reputation" beforehand. In Baldung we see the foreground woman naked and from behind. Yet peering backward between her legs, she sees us first and, our sovereignty of judgment potentially destroyed, we cannot know whether we observe before us are ordinary women or witches at a sabbath.

Accompanying this evil eye within the picture are symptoms of a nameless, polymorphous power that seems at once to rage across and to emanate from Baldung's three nudes. It blasts the women's hair into surrounding spaces. It fuels the flame that, rhyming visually with the witches' hair bursts from the pot at the upper framing edge and explodes the picture's closure as it seems to pass out of the sheet....

/p. 332: At the hub is this maelstrom of bodies, and near the geometric center of the sheet, Baldung places the groin of the young, flame-bearing witch. This groin is also the point of intersection between the scene's two principal diagonals: the one carried by the flame-bearing witch's left leg, the other indicated by the old witch's right leg and by the leaning torso of her younger companion. It is hard, in a drawing as erotically charged as this, to discern a principle of decorum at work. Yet Baldung has chosen to cover with a hand the witch's sex, which otherwise would be gaping between her widespread legs. How are we to interpret this hand? One might propose that without it the drawing would simply have been beyond the limits of period propriety and that Baldung was therefore compelled to emplot his own or his audience's pudency by letting the witch appear to cover herself. Yet given the foreground witch's lewder posture, and observing the way two fingers of the concealing hand turn inward toward the hidden groin, one is tempted to suggest that, rather than covering herself, the standing witch is actually masturbating. I say /p. 333: "tempted," for there is no way to be certain whether this gesture is modest or wanton. Like the play of concealment in Baldung's images of the Fall, the chiaroscuro drawing demands that its viewers guess what is "really" going on. Eliciting this interpretation of its plot, the image reveals the viewer to be himself innocent or wanton and exposes him to the embarassment of having thought or said what lies beyond decorum.

Everything focuses on the female genitals but eddies back to the implied male viewer. Below and to the left of the concealed groin, the old witch's sex marks the approximate vanishing point of the picture's nominal construction of space. The long edges of the tablet in the foreground and, more clearly, the sheet's date and the artist's monogram inscribed upon it, converge as orthogonals about this groin. More strikingly, the third witch exposes her buttocks and pubes to the viewer as she bends over and looks between her legs. With her upside-down eyes aligned with her groin, she invites us to rotate the sheet so that her head appears at the top of the page and the flaming pot at the base. Thus reoriented, the flame can be read as a self-enflamed and enflaming vagina; the witches' nude bodies and flowing hair become the pubic triangle; and the sheet's reddish brown ground doubles as flesh.

Baldung frequently invokes the flaming or fuming pot to visualize the female body as an unclean chamber out of which pour all evils of the flesh. In the 1510 woodcut Sabbath, the corpulent foreground witch straddles a bulging vessel and lifts its lid to release stream of smoke, frogs, and debris. If the outlines of this stream are  extrapolated backward through the open pot, they converge at the witch's groin. The female sexual orifice as the source of an evil vapor finds far more direct expressions in Baldung's drawings of witches. Intended for a more limited audience, these sheets show openly what the more widely disseminated woodcut cloaks in visual metaphor. In a chiaroscuro drawing in the Louvre, dating from the same year as the Albertina sheet, a seated witch reaches between her legs to light a wand on flaming vapors that explode from between her legs. Above and to the right, the hair of her companions bursts forth with an equal and opposite force; and at the lower right, a cat exhales or vomits similar fumes. Such a drawing exhibits a misogyny and a sexual terror that, while difficult for us to fathom today, are common throughout medieval art and literature. Like the popular images of Frau Welt, it visualizes woman as corrupt and corrupting flesh. In The Plowman of Bohemia, composed about 1400, Death reminds its victim that he was "conceived in sin [and] nourished in the maternal body by an unclean, unnamed monstrosity" and that he in turn is himself "a wholly ugly thing, a shitbag, an unclean food, a stinkhouse, a repulsive washbasin, a rotting carcass, a mildewed box, a bottomless bag... a foul-smelling piss-pot, a foul-tasting pail." The body is born a macabre corpse from a tomb-like womb. From this perspective, Baldung's witches are indeed variations of his images of death. They conflate the sensual lure of the nude female body with the polluted, uncanny interior of the festering cadaver.

extrapolated backward through the open pot, they converge at the witch's groin. The female sexual orifice as the source of an evil vapor finds far more direct expressions in Baldung's drawings of witches. Intended for a more limited audience, these sheets show openly what the more widely disseminated woodcut cloaks in visual metaphor. In a chiaroscuro drawing in the Louvre, dating from the same year as the Albertina sheet, a seated witch reaches between her legs to light a wand on flaming vapors that explode from between her legs. Above and to the right, the hair of her companions bursts forth with an equal and opposite force; and at the lower right, a cat exhales or vomits similar fumes. Such a drawing exhibits a misogyny and a sexual terror that, while difficult for us to fathom today, are common throughout medieval art and literature. Like the popular images of Frau Welt, it visualizes woman as corrupt and corrupting flesh. In The Plowman of Bohemia, composed about 1400, Death reminds its victim that he was "conceived in sin [and] nourished in the maternal body by an unclean, unnamed monstrosity" and that he in turn is himself "a wholly ugly thing, a shitbag, an unclean food, a stinkhouse, a repulsive washbasin, a rotting carcass, a mildewed box, a bottomless bag... a foul-smelling piss-pot, a foul-tasting pail." The body is born a macabre corpse from a tomb-like womb. From this perspective, Baldung's witches are indeed variations of his images of death. They conflate the sensual lure of the nude female body with the polluted, uncanny interior of the festering cadaver.

Sigrid Schade has linked Baldung's Louvre Witches' Sabbath more specfically to two pseudoclassical tales of the power of women that were current in the artist's culture.  The woman as dangerous pot recalls the story of Pandora as it was told in the Renaissance. /p. 335: In an intensely misogynist play of 1514, for example, the Nuremberg preach Leonhard Culman identifies the "beautiful Pandora" with the box that had become her attribute. Both are the containers of "lust and pleasure" and instruments of the devil. And long before that, the church fathers, attempting to corroborate their doctrine of original sin by classical parallel, likened Pandora to Eve and her vessel to the forbidden fruit. The notion of Eva prima Pandora, monumentalized in Jean Cousin's picture of that title in the Louvre, would have appealed to Baldung as a bridge between his witches and his images of the Fall....

The woman as dangerous pot recalls the story of Pandora as it was told in the Renaissance. /p. 335: In an intensely misogynist play of 1514, for example, the Nuremberg preach Leonhard Culman identifies the "beautiful Pandora" with the box that had become her attribute. Both are the containers of "lust and pleasure" and instruments of the devil. And long before that, the church fathers, attempting to corroborate their doctrine of original sin by classical parallel, likened Pandora to Eve and her vessel to the forbidden fruit. The notion of Eva prima Pandora, monumentalized in Jean Cousin's picture of that title in the Louvre, would have appealed to Baldung as a bridge between his witches and his images of the Fall....

Yet in Baldung's Louvre sheet, the women are more than merely "like" unclean boxes, and the wand, pitchfork, and sausages they place between their legs are more than merely "symbols" of the phallus. Baldung pretends to expose the hidden reality behind the legends of women's power. Witches, he wants his viewer to believe, themselves use their bodies as diabolical vessels and create, manipulate, and enchant phallic objects of their own carnal pleasures and malevolent plots. Sausage and wand are therefore not the artist's symbols of the penis, but the witch's. With them she can variously stimulate herself, cause erection and impotence in men, and induce fantasies of castration....

/p. 355: It is hard to judge whether Baldung's art satirizes or merely reflects late medieval technologies of self. The unusually lewd things his pictures show might be intended simply to heighten an admonition against lust; that these pictures themselves become lewd or pornographic would then be an unintended by-product of their didactic purpose. Or alternatively, Baldung might want his pictures to exceed their moral brief so that they can expose as futile any human attempt at righteousness, whether of the viewer or of the artist. The line between complicity and critique, or between unintended and intended effects, is notoriously difficult to draw. Other German artists of the period, it is true, propose markedly different alignments. Lucas Cranach the Elder's mythological paintings always convey some moralizing message, yet their main effect is to please us with their decorative design and to titillate us with their mild eroticism.

The contradiction between what an image means and what it does evinces little pathos: Cranach can simultaneously and unabashedly warn against vice and exploit vice's sensual charms. Measured against such sweet medicine, Baldung's images are certainly more critical of their own more lewd eroticism. The New Year's Sheet, I have argued, focuses this critique. By naming the work's recipient as the sabbath's missing devil, and by including Baldung's monogram within the depicted malevolence, the drawing accuses both its viewer and its maker of being drawn to evil even as they pretend to reject it. The Chor Kappe may judge the nude women to be witches; as potential confessor and inquisitor, and vowed to celibacy, he may even be specifically ordained to make this judgment; yet he will nonetheless desire carnally what he condemns.