Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 209 Assignments

Archaic Sculpture

Beaten bronze figures of Apollo, Artemis, and Leto from the temple of Apollo at Dreros on Crete, c. 700 B.C.

Bronze man from Thebes. The dedication by Mantiklos is written on the thighs: "Mantiklos offers me as a tithe to Apollo of the silver bow; do you, Phoibos, give some pleasing favor in return." Early 7th c.

Life-size standing statue of a woman dedicated by one Nikandre to Artemis on Delos, 3rd quarter of the 7th c. B.C.. Inscription: "Nikandre dedicated me to the far-shooter of arrows [Artemis], the excellent daughter of Deinodikes of Naxos, sister of Deinomenes, wife of Praxos...."

Bronze "Kouros" from Delphi, c. 630.

Mentuemhet, prince of Egyptian Thebes, from Karnak, 713-664.

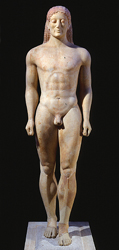

"Metropolitan Kouros", c. 600-575 B.C.

Ranofer, Egyptian, 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, c. 2400 B.C.

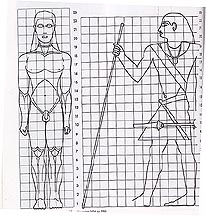

The Metropolitan Kouros and the second Egyptian canon (after c. 680).

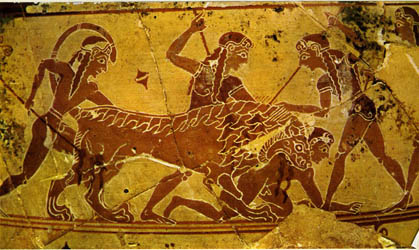

Detail of the Chigi Vase, mid 7th century.

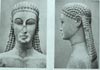

Dipylon Head, c. 600-575.

Sounion Kouros, c. 600-590 B.C. Found at the sanctuary of Poseidon at Sounion

Head of Sounion Kouros.

Kouros from Tenea, c. 550 B.C.

Detail of Head of Tenea Kouros

Kroisos, kouros from Anavysos, c. 540-515. Stood on stepped base with the following inscription: "Stay and mourn at the monument for dead Kroisos whom violent Ares destroyed, fighting in the front rank."

Aristodikos Kouros, from Attica, c. 500 BCE. Gravemarker of Aristodikos.

Texts

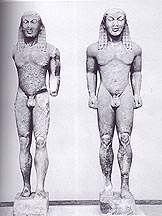

Two kouroi (Kleobis and Biton?) signed by [Poly]medes of Argos, from Delphi, c. 600-575.

Story of Kleobis and Biton: Herodotus I, 31:

[1] When Solon had provoked him by saying that the affairs of Tellus were

so fortunate, Croesus asked who he thought was next, fully expecting to win

second prize. Solon answered, “Cleobis and Biton.

[2] They were of Argive stock, had enough to live on, and on top of this had

great bodily strength. Both had won prizes in the athletic contests, and this

story is told about them: there was a festival of Hera in Argos, and their

mother absolutely had to be conveyed to the temple by a team of oxen. But

their oxen had not come back from the fields in time, so the youths took the

yoke upon their own shoulders under constraint of time. They drew the wagon,

with their mother riding atop it, traveling five miles until they arrived

at the temple.

[3] When they had done this and had been seen by the entire gathering, their

lives came to an excellent end, and in their case the god made clear that

for human beings it is a better thing to die than to live. The Argive men

stood around the youths and congratulated them on their strength; the Argive

women congratulated their mother for having borne such children.

[4] She was overjoyed at the feat and at the praise, so she stood before the

image and prayed that the goddess might grant the best thing for man to her

children Cleobis and Biton, who had given great honor to the goddess.

[5] After this prayer they sacrificed and feasted. The youths then lay down

in the temple and went to sleep and never rose again; death held them there.

The Argives made and dedicated at Delphi statues of them as being the best

of men.”

Diodorus Siculus (late first century B.C.), Library,

I, 98, 5-9:

“Among the old sculptors who are particularly mentioned as having spent

time among them [the Egyptians] are Theodorus and Telekles, the sons of Rhoikos,

who made the statue of Pythian Apollo for the Samians. Of this image it is

related that half of it was made by Telekles in Samos, while, at Ephesus,

the other half was finished by his brother Theodoros, and that when the parts

were fitted together with one another, they corresponded so well that they

appeared to have been made by one person. This type of workmanship is not

practiced at all among the Greeks, but among the Egyptians it is especially

common. For among them the symmetria of statues is not calculated according

to the appearances which are presented by the eyes, as they are among the

Greeks; but rather, when they have laid out the stones, and, after dividing

them up, begin to work on them, at this point they select a module from the

smallest parts which can be applied to the largest. Then dividing up the lay-out

of the body into twenty-one parts, plus an additional one-quarter, they produce

all the proportions of the living figure. Therefore, when the artists agree

with one another about the size of a statue, they separate from each other,

and execute the parts of the work for which the size has been agreed with

such precision that their particular way of working is a cause of astonishment.

The statue of Samos, in accordance with the technique of the Egyptians, is

divided into two parts by a line which runs from the top of the head, through

the middle of the figure to the groin, thus dividing the figure into two equal

parts. They say that his statue is, for the most part, quite like those of

the Egyptians, because it has the hands suspended at its sides, and the legs

parted as if in walking.