Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 220

Gender and Sexuality in European Art from the Late Nineteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries

|

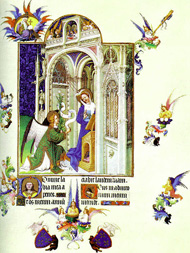

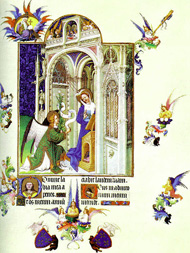

The Eva / Ave dichotomy has been a recurring theme in western art. In Medieval Art, Eve was regularly paired with her anti-type, the Virgin Mary (Ave). The Limbourgs placed an image of the Fall of Man opposite the Annunciation in the Très riches heures. The Virgin Birth with Christ's Incarnation along with his Death and Resurrection were the central events in the Christian plan of history. It allowed for the Redemption of human kind from the Original Sin of Adam and Eve. The story of Eve's role in the Fall was at the foundation of western misogyny and justification for patriarchal authority. Of course, the female as the root of all evil had its parallel in the Greek myth of Pandora. In a remarkable series of images, the German sixteenth century Hans Baldung explores the implications of temptation. Sexuality and death are the two sides of the coin of the Temptation:

The constructed male observer of these paintings as a Son of Adam finds pleasure at admiring the eroticized body of Eve but death is the consummation of this desire. For more on these Baldung paintings see the excerpts from Joseph Koerner's The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art.

The Virgin Mary, the other side of the Eva /Ave dichotomy, presented women with an impossible ideal as a Virgin Mother. But images of the Virgin and Child have played a central role in constructing western ideas of motherhood as the following examples demonstrate:

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self Portrait with her Daughter, c. 1789. |

These themes of maternity, sexuality, and death fascinated artists especially at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. It is important to see the link between the popularity of these archetypal themes in the art of the period and the development of the thought of Sigmund Freud. Gustav Klimt and Freud were a part of the same intellectual circle in fin de siècle Vienna. As a journal assignment, explore these themes in the following gallery of images. Read the following articles which develop these themes. Include in your journal a brief abstract of at least two of these articles.

In thinking about these works, consider the following quotation by Patricia Berman in her Munch and Women: Image and Myth. She makes the following distinction between images of women and images of the archetypal Woman:

| Munch's representations of women are frequently conflated in the critical literature with his representations of "Woman." A turn-of-the-century literary and artistic trope, Woman was the collective invention of a male cultural invention of a male cultural imagination. An essentializing, timeless, and at times malevolent being. Woman was a stereotype that erased the complexity and diversity of women. Deployed by male intellectuals as a way of negating women's claims to increasing social and economic geography, Woman was sexualized and silenced the cultural presence of real women. In Reinhold Heller's words, Woman was shaped by males "subconscious desires, fears and anxieties that became self-perpetuating," rather than by "the experience of real women." Woman was a myth that devitalized and replaced women's lived experiences [p. 11]. |

Notice how in contrast to the male artists included in this gallery, Mary Cassatt, while still referring to archetypal themes, constructs her images to create what we might consider a "reality effect" where the figures have the semblance of particular people in the modern world.

Wendy Slatkin, "Maternity and Sexuality in the 1890s" Woman's Art Journal, I, 1980, pp. 13-19 (JSTOR Link)

Norma Broude, "Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman or the Cult of True Womanhood?," Woman's Art Journal, 21, 2000-2001, pp. 36-43. (JSTOR Link)

Kristie Jayne, "The Cultural Roots of Edvard Munch's Images of Women," Woman's Art Journal, 10, 1989, pp. 28-34 (JSTOR Link)

Jan Thompson, "The Role of Woman in the Iconography of Art Nouveau," Art Journal, 31, 1971-72, pp. 158-167 ( JSTOR Link)

[If you use a computer on campus, the JSTOR link should work. If you are using an off-campus computer, you will need to log into JSTOR at the Milne Library page. You can then search JSTOR for the particular article.]

Paul Gauguin, Ia Orana Maria (Hail Mary), 1891-92. |

||

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1894-95. |

|

|

Jan Toorop. The Three Brides, 1893, chalk and pencil. |

||

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907-08. |

Gustav Klimt, Judith I, 1901. |

|

Gustav Klimt, Danae, 1907-08. |

||

Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing Before Herod , 1876, (for late nineteenth century images of Salome see Brad Bucknell, "On 'Seeing' Salome," ELH, 60, 1993, pp. 503-526. (JSTOR Link ) (The following quotation comes from J. K. Huysmans novel À rebours (or Against the Grain), published in 1884 . In this passage the major character Des Esseintes presents his response to the Moreau painting: In Gustave Moreau's work, conceived independently of the Testament themes, Des Esseintes as last saw realized the superhuman and exotic Salomé of his dreams. She was no longer the mere performer who wrests a cry of desire and of passion from an old man by a perverted twisting of her loins; who destroys the energy and breaks the will of a king by trembling breasts and quivering belly. She became, in a sense, the symbolic deity of indestructible lust, the goddess of immortal Hysteria, of accursed Beauty, distinguished from all others by the catalepsy which stiffens her flesh and hardens her muscles; the monstrous Beast, indifferent, irresponsible, insensible, baneful, like the Helen of antiquity, fatal to all who approach her, all who behold her, all whom she touches.) |

||

Aubrey Beardsley, The Climax (Salome holding the head of John the Baptist), 1893. Illustration for Oscar Wilde's play Salomé. |

||

Rodin, The Kiss, displayed for the first time in 1898. |

||

Related Web Sites:

Edvard Munch: The Dance of Life