Art

Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH

213 Assignments

Excerpt from Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists:

Michelangelo

BUONAROTTI of Florence, Painter, Sculptor and Architect

(1475-1564)

For primary documents concerning Michelangelo's career, samples of Michelangelo's poems, and Vasari's biography of Michelangelo see the pdf on the Columbia University Art and Humanities site.

WHILE industrious and choice

spirits, aided by the light afforded by Giotto and his followers, strove to

show the world the talent with which their happy stars and well-balanced humours

had endowed them, and endeavoured to attain to the height of knowledge by imitating

the greatness of Nature in all things, the great Ruler of Heaven looked down

and, seeing these vain and fruitless efforts and the presumptuous opinion of

man more removed from truth than light from darkness, resolved, in order to

rid him of these errors, to send to earth a genius universal in each art, to

show single-handed the perfection of line and shadow, and who should give relief

to his paintings, show a sound judgment in sculpture, and in architecture should

render habitations convenient, safe, healthy, pleasant, well-proportioned, and

enriched with various ornaments. He further endowed him with true moral philosophy

and a sweet poetic spirit, so that the world should marvel at the singular eminence

of his life and works and all his actions, seeming rather divine than earthy.

In the arts of painting,

sculpture and architecture the Tuscans have always been among the best, and

Florence was the city in Italy most worthy to be the birthplace of such a citizen

to crown her perfections. Thus in 1474 the true and noble wife of Ludovico di

Lionardo Buonarotti Simone, said to be of the ancient and noble family of the

Counts of Canossa, gave birth to a son in the Casentino, under a lucky star.

The son was born on Sunday, 6 March, at eight in the evening, and was called

Michelangelo, as being of a divine nature, for Mercury and Venus were in the

house of Jove at his birth, showing that his works of art would be stupendous.

Ludovico at the time was

podesta at Chiusi and Caprese near the Sasso della Vernia, where St. Francis

received the stigmata, in the diocese of Arezzo. On laying down his office Ludovico

returned to Florence, to the villa of Settignano, three miles from the city,

where he had a property inherited from his ancestors, a place full of rocks

and quarries of macigno which are constantly worked by stonecutters and sculptors

who are mostly natives. There Michelangelo was put to nurse with a stonecutter's

wife. Thus he once said jestingly to Vasari: "What good I have comes from

the pure air of your native Arezzo, and also because I sucked in chisels and

hammers with my nurse's milk." In time Ludovico had several children, and

not being well off, he put them in the arts of wool and silk. Michelangelo,

who was older, he placed with Maestro Francesco da Urbino to school. But the

boy devoted all the time he could to drawing secretly, for which his father

and seniors scolded and sometimes beat him, thinking that such things were base

and unworthy of their noble house.

About this time Michelangelo

made friends with Francesco Granacci, who though quite young had placed himself

with Domenico del Ghirlandaio to learn painting. Granacci perceived Michelangelo's

aptitude for design, and supplied him daily with drawings of Ghirlandaio, then

reputed to be one of the best masters not only in Florence but throughout Italy.

Michelangelo's desire to achieve thus increased daily, and Ludovico perceiving

that he could not prevent the boy from studying design, resolved to derive some

profit from it, and by the advice of friends put him with Domenico Ghirlandaio

that he might learn the profession. At that time Michelangelo was fourteen years

old. The author of his Life, written after 1550 when I first published this

work, has stated that some through not knowing him have omitted things worthy

of note and stated others that are not true, and in particular he taxes Domenico

with envy, saying that he never assisted Michelangelo.

This is clearly false, as

may be seen by a writing in the hand of Ludovico written in the books of Domenico

now in the possession of his heirs. It runs thus: "1488. bow this 1st April

that I Ludovico di Lionardo Buonarroto apprentice my son Michelangelo to Domenico

and David di Tommaso di Currado for the next three years, with the following

agreements: that the said Michelangelo shall remain‚ with them that time

to learn to paint and practise that art and shall do what they bid him, and

they shall give him 24 florins in the three years, 6 in the first, 8 in the

second and 10 in the third, in all 96 lire". Below this Ludovico has written:

"Michelangelo has received 2 gold florins this 16th April, and I Ludovico

di Lionardo, his father, have received 12 lire 12 soldi." I have copied

this from the book to show that I have written the truth, and I do not think

that there is anyone who has seen more of Michelangelo, who has been a greater

and more faithful friend to him, or who can show a larger number of autograph

letters than I. I have made this digression in the interests of truth, and let

this suffice for the rest of the life. We will now return to the story.

Michelangelo's progress

amazed Domenico when he saw him doing things beyond a boy, for he seemed likely

not only to surpass the other pupils, of whom there were a great number, but

would also frequently equal the master's own works.- One of the youths happened

one day to have made a pen sketch of draped women by his master, Michelangelo

took the sheet, and with a thicker pen made a new outline for one of the women,

representing her as she should be and making her perfect. The difference between

the two styles is as marvellous as the audacity of the youth whose good judgment

led him to correct his master. The sheet is now in my possession, treasured

as a relic. I had it from Granaccio with others of Michelangelo, to place in

the Book of Designs. In 1550, when Giorgio showed it to Michelangelo at Rome,

he recognised it with pleasure, and modestly said that he knew more of that

art when a child than later on in life [Compare this story to the attitudes

expressed by Cenino Cennini.

Imagine the craftsman trained by Cennini "correcting his master."

Also notice how Vasari treats this drawing as a "relic." Understand

the role of relics in the religious life of this period where these objects

served as miraculous links to the spiritual realm. The attitude expressed by

Vasari here anticipates the reverence shown to works of art in the modern museum

where we see the works as links to the "Great Masters."]

One day, while Domenico

was engaged upon the large chapel of S. Maria

Novella, Michelangelo drew the scaffolding and all the materials with some

of the apprentices at work. When Domenico returned and saw it, he said, "He

knows more than I do," and remained amazed at the new style produced by

the judgment of so young a boy, which was equal to that of an artist of many

years' experience.  To this Michelangelo added study and diligence so that he

made progress daily, as we see by a copy of a print engraved by Martin the German

[Martin Schongauer], which brought him great renown. When a copper engraving

by Martin of St. Anthony beaten by the devils reached Florence, Michelangelo

made a pen drawing and then painted it. To counterfeit some strange forms of

devils he bought fish with curiously coloured scales, and showed such ability

that he won much credit and reputation. He also made perfect copies of various

old masks, making them look old with smoke and other things so that they could

not be distinguished from the originals. He did this to obtain the originals

in exchange for the copies, as he wanted the former and sought to surpass them,

thereby acquiring a great name [Notice how Michelangelo does not just copy,

but outdoes the original. Michelangelo has thus outdone his own master and by

implication contemporary Florentine art but he has also outdone Northern European

art as represented by the Schongauer story].

To this Michelangelo added study and diligence so that he

made progress daily, as we see by a copy of a print engraved by Martin the German

[Martin Schongauer], which brought him great renown. When a copper engraving

by Martin of St. Anthony beaten by the devils reached Florence, Michelangelo

made a pen drawing and then painted it. To counterfeit some strange forms of

devils he bought fish with curiously coloured scales, and showed such ability

that he won much credit and reputation. He also made perfect copies of various

old masks, making them look old with smoke and other things so that they could

not be distinguished from the originals. He did this to obtain the originals

in exchange for the copies, as he wanted the former and sought to surpass them,

thereby acquiring a great name [Notice how Michelangelo does not just copy,

but outdoes the original. Michelangelo has thus outdone his own master and by

implication contemporary Florentine art but he has also outdone Northern European

art as represented by the Schongauer story].

At this time Lorenzo de'

Medici the Magnificent kept Bertoldo the sculptor in his garden on the piazza

of S. Marco, not so much the custodian of the numerous collections of beautiful

antiquities there, as because he wished to create a school of great painters

and sculptors with Bertoldo as the head, who had been pupil of Donato [Donatello].

Although old and unable to work, he was a master of skill and repute, having

diligently finished Donato's pulpits and cast many bronze reliefs of battles

and other small things, so that no one then in Florence could surpass him in

such things. Lorenzo, who loved painting and sculpture, was grieved that no

famous sculptors lived in his day to equal the great painters who then flourished,

and so he resolved to found a school.

Accordingly

he asked Domenico Ghirlandaio that if he had any youths in his shop inclined

to this he should send them to the garden, where he would have them instructed

so as to do honour to him and to the city. Domenico elected among others Michelangelo

and Francesco Granaccio as being the best. At the garden they found that Torrigiano

was modelling clay figures given to him by Bertoldo.

Seeing that in addition the boy had opened its mouth and made the tongue and

all the teeth, Lorenzo jestingly said, for he was a pleasant man, "You

ought to know that the old never have all their teeth, and always lack some."

Michelangelo, who loved and respected his patron, took him seriously in his

simplicity, and so soon as he was gone he broke out a tooth and made the gum

look as if it had fallen out. He anxiously awaited the return of Lorenzo, who,

when he saw Michelangelo's simplicity and excellence, laughed more than once,

and related the matter to his friends as a marvel. He returned to help and favour

the youth, and sending for his father, Ludovico, asked him to allow him to treat

the boy as his own son, a request that was readily granted. Accordingly Lorenzo

gave Michelangelo. a room in the palace, and he ate regularly at table with

the family and other nobles staying there. This was the year after he had gone

to Domenico, when he was fifteen or sixteen, and he remained in the house for

four years until after the death of Lorenzo in 1492. I hear that he received

a provision at this time from Lorenzo and five ducats a month to help his father.

The Magnificent also gave him a violet mantle, and conferred an office in the

customs upon his father. Indeed all the youths in the garden received a greater

or less salary from that noble citizen, as well as rewards.

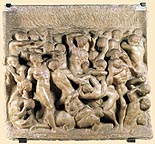

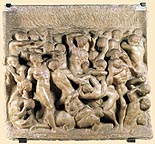

By

the advice of Poliziano,

the famous man of letters, Michelangelo did a fight between Hercules and the

Centaurs on a piece of marble given him by that signor, of such beauty that

it seems the work of a consummate master and not of a youth [compare to Late Antique Battle Sarcophagi like the Ludovisi]. It is now preserved

in his house by his nephew Lionardo as a precious treasure, in memory of him.

By

the advice of Poliziano,

the famous man of letters, Michelangelo did a fight between Hercules and the

Centaurs on a piece of marble given him by that signor, of such beauty that

it seems the work of a consummate master and not of a youth [compare to Late Antique Battle Sarcophagi like the Ludovisi]. It is now preserved

in his house by his nephew Lionardo as a precious treasure, in memory of him.

Not

many years since this Lionardo had a Madonna in bas-relief by his uncle, more

than a braccia high, in imitation of Donatello's style, so fine that it seems

the world of that master, except that it possesses more grace and design. Lionardo

gave it to Duke Cosimo, who values it highly, as he possesses no other bas-relief

of the master.

Not

many years since this Lionardo had a Madonna in bas-relief by his uncle, more

than a braccia high, in imitation of Donatello's style, so fine that it seems

the world of that master, except that it possesses more grace and design. Lionardo

gave it to Duke Cosimo, who values it highly, as he possesses no other bas-relief

of the master.

To return to Lorenzo's garden.

It was full of antiquities and excellent paintings, collected there for beauty,

study and pleasure. Michelangelo had the keys, and was much more studious than

the others in every direction, and always showed his proud spirit. For many

months he drew Masaccio's paintings in the Carmine [this refers to the Brancacci Chapel frescos], showing such judgment that

he amazed artists and others, and also roused envy. It is said that Torrigiano

made friends with him, but moved by envy at seeing him more honoured and skilful

than himself, struck him so hard on the nose that he broke it and disfigured

him for life. For this Torrigiano was banished from Florence, as is related

elsewhere.

On the death of Lorenzo

Michelangelo returned home, much grieved at the loss of that great man and true

friend of genius. Buying a large block of marble, he made a Hercules of four

braccia, which stood for many years in the Strozzi palace, and was considered

remarkable. In the year of the siege it was sent to King Francis of France by

Giovambattista della Palla. It is said that Piero de' Medici, who had long associated

with Michelangelo, often sent for him, wishing to buy antique cameos and other

intaglios, and one snowy winter he got him to make a beautiful snow statue in

the court of his palace. He so honoured Michelangelo for his ability that his

father, seeing him in such favour with the great, clothed him much more sumptuously

than before.

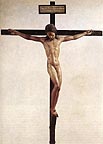

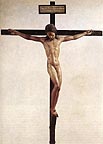

For

S. Spirito in Florence Michelangelo made a wooden crucifix, put over the lunette

above the high altar to please the prior, who gave him suitable rooms, where

he was able, by frequently dissecting dead bodies, to study anatomy, and thereby

he began to perfect his great design....

For

S. Spirito in Florence Michelangelo made a wooden crucifix, put over the lunette

above the high altar to please the prior, who gave him suitable rooms, where

he was able, by frequently dissecting dead bodies, to study anatomy, and thereby

he began to perfect his great design....

M.

Jacopo Galli, an intelligent Roman noble, recognised Michelangelo's ability,

and employed him to make a marble Cupid of life-size, and then to do a Bacchus

of ten palms holding a cup in the right hand, and in the left a tiger's skin

and a bunch of grapes with a satyr trying to eat them.a This figure shows that

he intended a marvellous blending of limbs, uniting the slenderness of a youth

with the fleshy roundness of the female, proving Michelangelo's superiority

to all the moderns in statuary.

M.

Jacopo Galli, an intelligent Roman noble, recognised Michelangelo's ability,

and employed him to make a marble Cupid of life-size, and then to do a Bacchus

of ten palms holding a cup in the right hand, and in the left a tiger's skin

and a bunch of grapes with a satyr trying to eat them.a This figure shows that

he intended a marvellous blending of limbs, uniting the slenderness of a youth

with the fleshy roundness of the female, proving Michelangelo's superiority

to all the moderns in statuary.

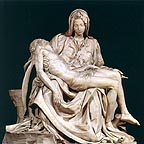

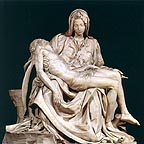

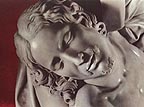

During his stay in Rome

he made such progress in art that his conceptions were marvellous, and he executed

difficulties with the utmost ease, frightening those who were not accustomed

to see such things, for when they were done the works of others appeared as

nothing beside them. Thus the cardinal of St. Denis, called Cardinal Rohan,

a Frenchman, desired to leave a memorial of himself in the famous city by such

a rare artist, and got him to do a marble Pieta, which was placed in the chapel

of S. Maria della Febbre in the temple of Mars, in S. Pietro. The rarest artist

could add nothing to its design and grace, or finish the marble with such polish

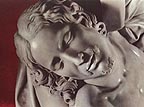

and art, for it displays the utmost limits of sculpture. Among its beauties

are the divine draperies, the foreshortening of the dead Christ and the beauty

of the limbs with the muscles, veins, sinews, while no better presentation of

a corpse was ever made.  The

sweet air of the head and the harmonious joining of the arms and legs to the

torso, with the pulses and veins, are marvellous, and it is a miracle that a

once shapeless stone should assume a form that Nature with difficulty produces

in flesh. Michelangelo devoted so much love and pains on this work that he put

his name on the girdle crossing the Virgin's breast, a thing he never did again.

One morning he had gone to the place to where it stands and observed a number

of Lombards who were praising it loudly. One of them asked another the name

of the sculptor, and he replied, "Our Gobbo of Milan." Michelangelo

said nothing, but he resented the injustice of having his work attributed to

another, and that night he shut himself in the chapel with a light and his chisels

and carved his name on it. It has been thus aptly described:

The

sweet air of the head and the harmonious joining of the arms and legs to the

torso, with the pulses and veins, are marvellous, and it is a miracle that a

once shapeless stone should assume a form that Nature with difficulty produces

in flesh. Michelangelo devoted so much love and pains on this work that he put

his name on the girdle crossing the Virgin's breast, a thing he never did again.

One morning he had gone to the place to where it stands and observed a number

of Lombards who were praising it loudly. One of them asked another the name

of the sculptor, and he replied, "Our Gobbo of Milan." Michelangelo

said nothing, but he resented the injustice of having his work attributed to

another, and that night he shut himself in the chapel with a light and his chisels

and carved his name on it. It has been thus aptly described:

Bellezza ed onestate

E doglia e pieta on vivo marmo morte,

Deh, come voi pur fate

Nort piangete si forte

Che anzi tempo risveglisi da morte

E pur, mai grado suo

Nostro Signore e tuo

Sposo, figliuolo e padre

Unica sposa sua figliuola e madre.

|

It

brought him great renown, and though some fools say that he has made the Virgin

too young, they ought to know that spotless virgins keep their youth for a long

time, while people afflicted like Christ do the reverse, so that should contribute

more to increase the fame of his genius than all the things done before.

It

brought him great renown, and though some fools say that he has made the Virgin

too young, they ought to know that spotless virgins keep their youth for a long

time, while people afflicted like Christ do the reverse, so that should contribute

more to increase the fame of his genius than all the things done before.

Some of Michelangelo's friends

wrote from Florence urging him to return, as they did not want that block of

marble on the opera to be spoiled which Piero Soderini, then gonfaloniere for

life in the city, had frequently proposed to give to Leonardo da Vinci, and

then to Andrea Contucci, an excellent sculptor, who wanted it. Michelangelo

on returning tried to obtain it, although it was difficult to get an entire

figure without pieces, and no other man except himself would have had the courage

to make the attempt, but he had wanted it for many years, and on reaching Florence

he made efforts to get it. It was nine braccia high, and unluckily one Simone

da Fiesole had begun a giant, cutting between the legs and mauling it so badly

that the wardens of S. Maria del Fiore had abandoned it without wishing to have

it finished, and it had rested so for many years. Michelangelo examined it afresh,

and decided that it could be hewn into something new while following the attitude

sketched by Simone, and he decided to ask the wardens and Soderini for it. They

gave it to him as worthless, thinking that anything he might do would be better

than its present useless condition.

Accordingly Michelangelo

made a wax model of a youthful David holding the sling to show that the city

should be boldly defended and righteously governed, following David's example.

He began it in the opera, making a screen between the wall and the tables, and

finished it without anyone having seen him at work. The marble had been hacked

and spoiled by Simone so that be could not do all that he wished with it, though

he left some of Simone's work at the end of the marble, which may still be seen.

This revival of a dead thing was a veritable miracle.  When it was finished various

disputes arose as to who should take it to the piazza of the Signori, so Giuliano

da Sangallo and his brother Antonio made a strong wooden frame and hoisted the

figure on to it with ropes; they then moved it forward by beams and windlasses

and placed it in position. The knot of the rope which held the statue was made

to slip so that it tightened as the weight increased, an ingenious device, the

design for which is in our book, showing a very strong and safe method of suspending

heavy weights. Piero Soderini came to see it, and expressed great pleasure to

Michelangelo who was retouching it, though he said he thought the nose large.

Michelangelo seeing the gonfaloniere below and knowing that he could not see

properly, mounted the scaffolding and taking his chisel dexterously let a little

marble dust fall on to the gonfaloniere, without, however, actually altering

his work. Looking down he said, "Look now." "I like it better,"said

the gonfaloniere, "you have given it life." Michelangelo therefore

came down with feelings of pity for those who wish to seem to understand matters

of which they know nothing. When the statue was finished and set up Michelangelo

uncovered it. It certainly bears the palm among all modern and ancient works,

whether Greek or Roman, and the Marforio of Rome, the Tiber and Nile of Belvedere,

and the colossal statues of Montecavallo do not compare with it in proportion

and beauty. The legs are finely turned, the slender flanks divine, and the graceful

pose unequalled, while such feet, hands and head have never been excelled. After

seeing this no one need wish to look at any other sculpture or the work of any

other artist. Michelangelo received four hundred crowns from Piero Soderini,

and it was set up in 15O4.

When it was finished various

disputes arose as to who should take it to the piazza of the Signori, so Giuliano

da Sangallo and his brother Antonio made a strong wooden frame and hoisted the

figure on to it with ropes; they then moved it forward by beams and windlasses

and placed it in position. The knot of the rope which held the statue was made

to slip so that it tightened as the weight increased, an ingenious device, the

design for which is in our book, showing a very strong and safe method of suspending

heavy weights. Piero Soderini came to see it, and expressed great pleasure to

Michelangelo who was retouching it, though he said he thought the nose large.

Michelangelo seeing the gonfaloniere below and knowing that he could not see

properly, mounted the scaffolding and taking his chisel dexterously let a little

marble dust fall on to the gonfaloniere, without, however, actually altering

his work. Looking down he said, "Look now." "I like it better,"said

the gonfaloniere, "you have given it life." Michelangelo therefore

came down with feelings of pity for those who wish to seem to understand matters

of which they know nothing. When the statue was finished and set up Michelangelo

uncovered it. It certainly bears the palm among all modern and ancient works,

whether Greek or Roman, and the Marforio of Rome, the Tiber and Nile of Belvedere,

and the colossal statues of Montecavallo do not compare with it in proportion

and beauty. The legs are finely turned, the slender flanks divine, and the graceful

pose unequalled, while such feet, hands and head have never been excelled. After

seeing this no one need wish to look at any other sculpture or the work of any

other artist. Michelangelo received four hundred crowns from Piero Soderini,

and it was set up in 15O4.

Owing to his reputation

thus acquired, Michelangelo did a beautiful bronze David for the gonfaloniere,

which he sent to France, and he‚ sketched out two marble medallions, one

for Taddeo Taddei, and now in his house, the other for Bartolommeo Pitti, which

was given by Fra Miniato Pitti of Monte Oliveto, a master of cosmography and

many sciences, especially painting, to his intimate friend Luigi Guicciardini.

These works were considered admirable. At the same time he sketched a marble

statue of St. Matthew in the opera of S. Maria del Fiore, which showed his perfection

and taught sculptors the way to make statues without spoiling them, by removing

the marble so as to enable them to make such alterations as may be necessary.

He also did a bronze Madonna in a circle, carved at the request of some Flemish

merchants of the Moscheroni, noblemen in their country, who paid him one hundred

crowns and sent it to Flanders.  His

friend, Agnolo Doni, citizen of Florence, and the lover of all beautiful works

whether ancient or modern, desired to have something of his. Michelangelo therefore

began a round painting of the Virgin kneeling and offering the Child to Joseph,

where he shows his marvellous power in the head of the Mother fixedly regarding

the beauty of the Child, and the emotion of Joseph in reverently and tenderly

taking it, which is obvious without examining it closely. As this did not suffice

to display his powers, he made seated, standing and reclining nude figures in

the background, completing the work with such finish and polish that it is considered

the finest of his few panel paintings. When finished he sent it wrapped up to

Agnolo's house, by a messenger, with a note and a request for seventy ducats

as payment. Agnolo being a careful man, thought this a large sum for one picture,

though he knew it was worth more. So he gave the bearer forty ducats, saying

that was enough. Michelangelo at once sent demanding one hundred ducats or the

return of the picture. Andrea being delighted with the picture, then agreed

to give seventy ducats, but Michelangelo being incensed by Agnolo's mistrust,

demanded double what he had asked the first time, and Agnolo, who wanted the

picture, was forced to send him one hundred and forty crowns.

His

friend, Agnolo Doni, citizen of Florence, and the lover of all beautiful works

whether ancient or modern, desired to have something of his. Michelangelo therefore

began a round painting of the Virgin kneeling and offering the Child to Joseph,

where he shows his marvellous power in the head of the Mother fixedly regarding

the beauty of the Child, and the emotion of Joseph in reverently and tenderly

taking it, which is obvious without examining it closely. As this did not suffice

to display his powers, he made seated, standing and reclining nude figures in

the background, completing the work with such finish and polish that it is considered

the finest of his few panel paintings. When finished he sent it wrapped up to

Agnolo's house, by a messenger, with a note and a request for seventy ducats

as payment. Agnolo being a careful man, thought this a large sum for one picture,

though he knew it was worth more. So he gave the bearer forty ducats, saying

that was enough. Michelangelo at once sent demanding one hundred ducats or the

return of the picture. Andrea being delighted with the picture, then agreed

to give seventy ducats, but Michelangelo being incensed by Agnolo's mistrust,

demanded double what he had asked the first time, and Agnolo, who wanted the

picture, was forced to send him one hundred and forty crowns.

When Leonardo da Vinci

was painting in the Great Hall of the Council, as related in his Life, Piero

Soderini,

the gonfaloniere, his great genius, and the artist chose the war of Pisa as

his subject. He was given a room in the dyers' hospital at S. Onofrio, and

there

began a large cartoon which he allowed no one to see. He filled it with nude figures bathing in the Arno owing to the heat, and running

in this condition to their arms on being attacked by the enemy. He represented

them hurrying out of the water to dress, and seizing their arms to go to assisttheir

comrades, some buckling their cuirasses and many putting on other armour,

while

others on horseback are beginning the fight. Among other figures is an old

man wearing a crown of ivy to shade his head trying to pull his stockings

on to

his wet feet, and hearing the cries of the soldiers and the beating of the

drums he is struggling violently, all his muscles to the tips of his toes

and his

contorted mouth showing the effects of the exertion. It also contained drums

and nude figures with twisted draperies running to the fray, foreshortened

in

extraordinary attitudes, some upright, some kneeling, some bent, and some lying.

There were also many groups sketched in various ways, some merely outlined

in

carbon, some with features filled in, some hazy or with white lights, to show

his knowledge of art. And indeed artists were amazed when they saw the lengths

he had reached in this cartoon. Some in seeing his divine figures declared

that it was impossible for any other spirit to attain to its divinity. When

finished

it was carried to the Pope's hall amid the excitement of artists and to the

glory of Michelangelo, and all those who studied and drew from it, as foreigners

and natives did for many years afterwards, became excellent artists, as we

see by Aristotile da Sangallo, his friend, Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, Raphael Sanzio,

Francesco Granaccio, Baccio Bandinelli, Alonso Berugetta a Spaniard, with Andrea

del Sarto, Franciabigio, Jacopo Sansovino, Rosso, Maturino, Lorenzetto, Tribolo,

then a child, Jacopo da Pontormo, and Perino del Vaga, all great Florentine

masters. Having become a school for artists, this cartoon was taken to the

great

hall of the Medici palace, where it was entrusted too freely to artists, for

during the illness of Duke Giuliano it was unexpectedly torn to pieces and

scattered

in many places, some fragments still being in the house of M. Uberto Strozzi,

a Mantuan noble, where they are regarded with great reverence, indeed they

are

more divine than human.

He filled it with nude figures bathing in the Arno owing to the heat, and running

in this condition to their arms on being attacked by the enemy. He represented

them hurrying out of the water to dress, and seizing their arms to go to assisttheir

comrades, some buckling their cuirasses and many putting on other armour,

while

others on horseback are beginning the fight. Among other figures is an old

man wearing a crown of ivy to shade his head trying to pull his stockings

on to

his wet feet, and hearing the cries of the soldiers and the beating of the

drums he is struggling violently, all his muscles to the tips of his toes

and his

contorted mouth showing the effects of the exertion. It also contained drums

and nude figures with twisted draperies running to the fray, foreshortened

in

extraordinary attitudes, some upright, some kneeling, some bent, and some lying.

There were also many groups sketched in various ways, some merely outlined

in

carbon, some with features filled in, some hazy or with white lights, to show

his knowledge of art. And indeed artists were amazed when they saw the lengths

he had reached in this cartoon. Some in seeing his divine figures declared

that it was impossible for any other spirit to attain to its divinity. When

finished

it was carried to the Pope's hall amid the excitement of artists and to the

glory of Michelangelo, and all those who studied and drew from it, as foreigners

and natives did for many years afterwards, became excellent artists, as we

see by Aristotile da Sangallo, his friend, Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, Raphael Sanzio,

Francesco Granaccio, Baccio Bandinelli, Alonso Berugetta a Spaniard, with Andrea

del Sarto, Franciabigio, Jacopo Sansovino, Rosso, Maturino, Lorenzetto, Tribolo,

then a child, Jacopo da Pontormo, and Perino del Vaga, all great Florentine

masters. Having become a school for artists, this cartoon was taken to the

great

hall of the Medici palace, where it was entrusted too freely to artists, for

during the illness of Duke Giuliano it was unexpectedly torn to pieces and

scattered

in many places, some fragments still being in the house of M. Uberto Strozzi,

a Mantuan noble, where they are regarded with great reverence, indeed they

are

more divine than human.

|

|

|

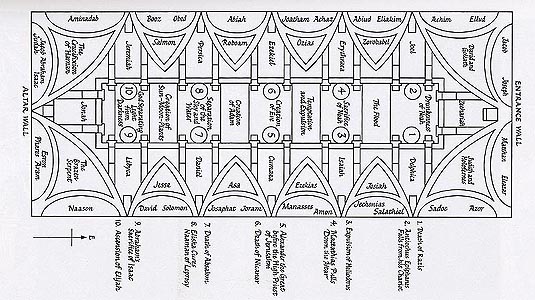

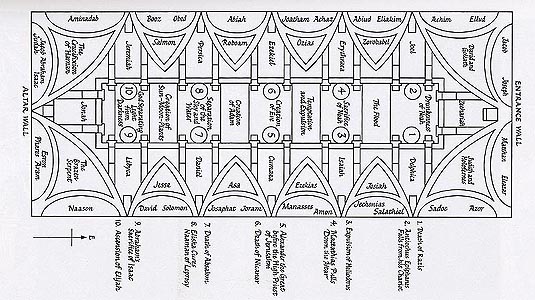

Reconstruction

of the 1505 plan of the Tomb of Julius II

|

The Pieta, the colossal

statue and the cartoon gave Michelangelo such a name that when, in 1503,

Julius

II. succeeded Alexander VI., he sent for the artist, who was then about twenty

nine, to make his tomb, paying him one hundred crowns for the journey. After

reaching Rome, it was many months before he did anything. At last he settled

on a design for the tomb, surpassing in beauty and richness of ornament

all

ancient and imperial tombs, affording the best evidence of his genius. Stimulated

by this, Julius decided to rebuild S. Pietro in order to hold the tomb,

as related

elsewhere. Michelangelo set to work with spirit, and first went to Cartara

to obtain all the marble, accompanied by two apprentices, receiving 1000

crowns

for this from AIamanno Salviati at Florence. He spent eight months there without

receiving any further provision, his mind being full of projects for making

great statues there as a memorial to himself, as the ancients had done, for

he felt the fascination of the blocks.

Having chosen his marble,

he sent it by sea to Rome, where it filled half the piazza of S. Pietro towards

S. Caterina, and the space between the church and the corridor leading to Castello.

Here Michelangelo made his studio for producing his figures and the rest of

the tomb. In order that the Pope might readily come to see him work, he made

a drawbridge from the corridor to the studio. His intimacy with the Pope grew

out of this, but it afterwards brought him great annoyance and persecution,

giving rise to much envy among artists. Of this work, during Julius's life and

after his death, Michelangelo did four complete statues and sketched eight,

as I shall relate.

The work being devised with

great invention, I will describe the ordering of it. Michelangelo wished it

to stand isolated, in arranged a series of niches separated by terminal figures

clothed order to make it appear larger, showing all four sides, from the middle

upwards and bearing the first cornice on their heads, each one in a curious

attitude and having a nude prisoner bound, standing on a projection from the

basement. These prisoners were to represent the provinces subdued by the Pope

and rendered obedient to the Church. Other statues, also bound, represented

the sciences and fine arts doomed to death like the Pope who had protected them.

At the corners of the first cornice were four large figures, Active and Contemplative

Life, St. Paul and Moses. Above the cornice the work was on a smalier scale

with a frieze of bronze bas-reliefs and other figures, infants and ornaments.

As a completion there were two figures above, one a smiling Heaven, supporting

the bier on her shoulders, with Cybele, goddess of the earth, who seems to grieve

that the world has lost such a man, while the other rejoices that his soul has

passed to celestial glory. There was an arrangement to enter at the top of the

work between the niches, and an oval place to move about in the middle, like

a church, in the midst of which the sarcophagus to contain the Pope's body was

to be placed. In all it was to have forty marble statues without counting the

reliefs, infants and ornaments, the carved cornices and other architectural

parts. For greater convenience Michelangelo ordered that a part of the marble

should be taken to Florence, where he proposed to spend the summer to escape

from the malaria of Rome. There he completed one face of the work in several

pieces, and at Rome divinely finished two prisoners and other statues which

are unsurpassed. That they might not be otherwise employed, he gave the prisoners

to Signor Ruberto Strozzi, in whose house Michelangelo had fallen sick. They

were afterwards sent to King Francis as a gift, and are now at Ecouen in France.

He sketched eight statues at Rome and five at Florence, and finished a  Victory

above a prisoner, now owned by Duke Cosimo, who had it from the artist's nephew

Lionardo.The duke has placed it in the great hall of the palace painted by Vasari.

Victory

above a prisoner, now owned by Duke Cosimo, who had it from the artist's nephew

Lionardo.The duke has placed it in the great hall of the palace painted by Vasari. Michelangelo finished the Moses in marble, a statue of five braccia, unequalled

by any modern or ancient work. Seated in a serious attitude, he rests with one

arm on the tables,

Michelangelo finished the Moses in marble, a statue of five braccia, unequalled

by any modern or ancient work. Seated in a serious attitude, he rests with one

arm on the tables, and with the other holds his long glossy beard, the hairs, so difficult to render

in sculpture, being so soft and downy that it seems as if the iron chisel must

have become a brush.

and with the other holds his long glossy beard, the hairs, so difficult to render

in sculpture, being so soft and downy that it seems as if the iron chisel must

have become a brush.  The

beautiful face, like that of a saint and mighty prince, seems as one regards

it to need the veil to cover it, so splendid and shining does it appear, and

so well has the artist presented in the marble the divinity with which God had

endowed that holy countenance. The draperies fall in graceful folds, the muscles

of the arms and bones of the hands are of such beauty and perfection, as are

tlie legs and knees, the feet being adorned with excellent shoes, that Moses

may now be called the friend of God more than ever, since God has permitted

his body to be prepared for the resurrection before the others by the hand of

Michelangelo. The Jews still go every Saturday in troops to visit and adore

it as a divine, not a human thing. At length he finished this part, which was

afterwards set up in S. Pietro ad Vincola.

The

beautiful face, like that of a saint and mighty prince, seems as one regards

it to need the veil to cover it, so splendid and shining does it appear, and

so well has the artist presented in the marble the divinity with which God had

endowed that holy countenance. The draperies fall in graceful folds, the muscles

of the arms and bones of the hands are of such beauty and perfection, as are

tlie legs and knees, the feet being adorned with excellent shoes, that Moses

may now be called the friend of God more than ever, since God has permitted

his body to be prepared for the resurrection before the others by the hand of

Michelangelo. The Jews still go every Saturday in troops to visit and adore

it as a divine, not a human thing. At length he finished this part, which was

afterwards set up in S. Pietro ad Vincola.

It is said that while Michelangelo

was engaged upon it, the remainder of the marble from Carrara arrived at Ripa,

and was taken with the rest to the piazza of S. Pietro. As it was necessary

to pay those who brought it, Michelangelo went as usual to the Pope. But the

Pope had that day received important news concerning Bologna, so Michelangelo

returned home and paid for the marble himself, expecting to be soon repaid.

He returned another day to speak to the Pope, and found difficulty in entering,

as a porter told him to wait, saying he had orders to admit no one. A bishop

said to the porter, "Perhaps you do not know this man." "I know

him very well," said the porter, "but I am here to execute my orders."

Unaccustomed to this treatment, Michelangelo told the man to inform the Pope

he was away when next His Holiness inquired for him. Returning home, he set

out post at two in the morning, leaving two servants with instructions to sell

his things to the Jews, and to follow him to Florence. Reaching Poggibonsi,

in Florentine territory, he felt safe, not being aware that five couriers had

arrived with letters from the Pope with orders to bring him back. But neither

prayers nor letters which demanded his return upon pain of disgrace moved him

in the least. However, at the instance of the couriers, he at length wrote a

few lines asking the Pope to excuse him, saying he would never return as he

had been driven away like a rogue, that his faithful service merited better

treatment, and that he should find someone else to serve him.

On reaching Florence, Michelangelo

finished in three months the cartoon of the great hall which Piero Soderini

the gonfaloniere desired him to finish. The Signoria received at that

time three letters from the Pope demanding that Michelangelo should be sent

back to Rome. On this account it is said that, fearing the Pope's wrath,

he

thought of going to Constantinople to serve the Turk by means of some Franciscan

friars, from between Constantinople and Pera. However, Piero Soderini persuaded

him, against his will, to go to the Pope, and sent him as ambassador of Florence,

to secure his person, to Bologna whither the Pope had gone from Rome, with

letters

of recommendation to Cardinal Soderini, the gonfaloniere's brother, who was

charged to introduce the Pope. There is another account of this departure

from

Rome: that the Pope was angry with Michelangelo, who would not allow him to

see any of his things. The artist suspected his assistants of having received

bribes from the Pope more than once to admit him to look at the chapel of

his

uncle Sixtus, which he was having painted, on certain occasions when Michelangelo

was not at home, or at work. It happened once that Michelangelo hid himself,

for he suspected the betrayal by his apprentices, and threw down some planks

as the Pope entered the chapel, and not thinking who it was, caused him to

be

summarily ejected. At all events,whatever the cause, he was angry with the

Pope and also afraid of him, and so he ran away.

Arrived at Bologna, he first

approached the footmen and was taken to the palace of the Sixteen by a bishop

sent by Cardinal Soderini, who was sick. He knelt before the Pope, who looked

wrathfully at him, and said as if in anger:' "Instead of coming to us,

you have waited for us to come and find you," inferring that Bologna is

nearer Florence than Rome. Michelangelo spread his hands and humbly asked for

pardon in a loud voice, saying he had acted in anger through being driven away,

and that he hoped for forgiveness for his error. The bishop who presented him

made excuses, saying that such men are ignorant of every- thing except their

art. At this the Pope waxed wroth, and striking the bishop with a mace he was

holding, said: "It is you who are ignorant, to reproach him when we say

nothing." The bishop therefore was hustled out by the attendants, and the

Pope's anger being appeased, he blessed Michelangelo, who was loaded with gifts

and promises, and ordered to prepare a bronze statue of the Pope, five braccia

high, in a striking attitude of majesty, habited in rich vestments, and with

determination and courage displayed in his countenance. This was placed in a

niche above the S. Petronio gate.

It is said that while Michelangelo

was engaged upon it Francia the painter came to see it, having heard much of

him and his works, but seen none. He obtained the permission, and was amazed

at Michelangelo's art. When asked what he thought of the figure, he replied

that it was a fine cast and good material. Michelangelo, thinking that he had

praised the bronze rather than the art, said: "I am under the same obligation

to Pope Julius, who gave it to me, as you are to those who provide your paints,''

and in the presence of the nobles he angrily called him a blockhead. Meeting

one day a son of Francia, who was said to be a very handsome youth, he said:

"Your father knows how to make living figures better than to paint them.''

One of the nobles asked him which was the larger, the Pope's statue or a pair

of oxen, and he replied, "It depends upon the oxen, those of Bologna are

certainly larger than our Florentine ones.'' Michelangelo finished the statue

in clay before the Pope left for Rome; His Holiness went to see it, and the

question was raised of what to put in the left hand, the right being held up

with such a proud gesture that the Pope asked if it was giving a blessing or

a curse. Michelangelo answered that he was admonishing the people of Bologna

to be prudent. When he asked the Pope whether he should put a book in his left

hand, the pontiff replied, "Give me a sword; I am not a man of letters."

The Pope left 1000 crowns wherewith to finish it in the bank of M. Antonmaria

da Lignano. After sixteen months of hard work it was placed in front of the

church of S. Petronio, as already related It was destroyed by the Bentivogli,

and the bronze sold to Duke Alfonso of Ferrara, who made a cannon of it, called

the Julius, the head only being preserved, which is now in his wardrobe.

After the Pope had returned

to Rome, and when Michelangelo had finished the statue, Bramante, the friend

and relation of Raphael and therefore ill-disposed to Michelangelo, seeing

the Pope's preference for sculpture, schemed to divert his attention, and

told the

Pope that it would be a bad omen to get Michelangelo to go on with his tomb,

as it would seem to be an invitation to death. He persuaded the Pope to

get

Michelangelo, on his return, to paint the vaulting of the Sistine Chapel. In this way Bramante and his other rivals hoped to confound him, for by taking

him from sculpture, in which he was perfect, and putting him to colouring

in

fresco, in which he had had no experience, they thought he would produce less

admirable work than Raphael, and even if he succeeded he would become embroiled

with the Pope, from whom they wished to separate him. Thus, when Michelangelo

returned to Rome, the Pope was disposed not to have the tomb finished for

the

time being, and asked him to paint the vaulting of the chapel. Michelangelo

tried every means to avoid it, and recommended Raphael, for he saw the difficulty

of the work, knew his lack of skill in coloring, and wanted to finish the

tomb.

In this way Bramante and his other rivals hoped to confound him, for by taking

him from sculpture, in which he was perfect, and putting him to colouring

in

fresco, in which he had had no experience, they thought he would produce less

admirable work than Raphael, and even if he succeeded he would become embroiled

with the Pope, from whom they wished to separate him. Thus, when Michelangelo

returned to Rome, the Pope was disposed not to have the tomb finished for

the

time being, and asked him to paint the vaulting of the chapel. Michelangelo

tried every means to avoid it, and recommended Raphael, for he saw the difficulty

of the work, knew his lack of skill in coloring, and wanted to finish the

tomb.

But the more he excused

himself, the more the impetuous Pope was determined he should do it, being stimulated

by the artist's rivals, especially Bramante, and ready to become incensed against

Michelangelo. At length, seeing that the Pope was resolute, Michelangelo decided

to do it. The Pope commanded Bramante to make preparations for the painting,

and he hung a scaffold on ropes, making holes in the vaulting. When Michelangelo

asked why he had done this, as on the completion of the painting it would be

necessary to fill up the holes again, Bramante declared there was no other way.

Michelangelo thus recognised either that Bramante was incapable or else hostile,

and he went to complain to the Pope that the scaffolding would not do, and that

Bramante did not know how it should be constructed. The Pope answered, in Bramante's

presence, that Michelangelo should design one for himself. Accordingly he erected

one on poles not touching the wall, a method which guided Bramante and others

in similar work. He gave so much rope to the poor carpenter who made it, that

it sufficed, when sold, for the dower of the man's daughter, to whom Michelangelo

presented it. He then got to work on the cartoons. The Pope wanted to destroy

the work on the walls done by masters in the time of Sixtus, and he set aside

15,000 ducats as the cost, as valued by Giuliano da San Gallo. Impressed by

the greatness of the work, Michelangelo sent to Florence for help, resolving

to prove himself superior to those who had worked there before, and to show

modern artists the true way to design and paint. The circumstances spurred him

on in his quest of fame and his desire for the good of art. When he had completed

the cartoons, he waited before beginning to colour them in fresco until some

friends of his, who were painters, should arrive from Florence, as he hoped

to obtain help from them, and learn their methods of fresco-painting, in which

some of them were experienced, namely Granaccio, Giulian Dugiardini, Jacopo

di Sandro, Indaco the elder, Agnolo di Donnino and Aristotile. He made them

begin some things as a specimen, but perceiving their work to be very far from

his expectations, he decided one morning to destroy everything which they had

done, and shutting himself up in the chapel he refused to admit them, and would

not let them see him in his house. This jest seemed to them to be carried too

far, and so they took their departure, returning with shame and mortification

to Florence.

Michelangelo then made arrangements

to do the whole work singlehanded. His care and labour brought everything into

excellent train, and he would see no one in order to avoid occasions for showing

anything, so that the most lively curiosity was excited. Pope Julius was very

anxious to see his plans, and the fact of their being hidden greatly excited

his desire. But when he went one day he was not admitted. This led to the disturbance

already referred to, when Michelangelo had to leave Rome. Michelangelo has himself

told me that, when he had painted a third of the vault, a certain mouldiness

began to appear one winter when the north wind was blowing. This was because

the Roman lime, being white and made of travertine, does not dry quickly enough,

and when mixed with pozzolana, which is of a tawny colour, it makes a dark mixture.

If this mixture is liquid and watery, and the wall thoroughly wetted, it often

effloresces in drying. This happened here, where the salt effloresced in many

places, although in time the air consumed it. In despair at this, Michelangelo

wished to abandon the work, and when he excused himself, telling the Pope that

he was not succeeding, Julius sent Giuliano da San Gallo, who explained the

difficulty and taught him how to obviate it. When he had finished half, the

Pope, who sometimes went to see it by means of steps and scaffolds, wanted it

to be thrown open, being an impatient man; unable to wait until it had received

the finishing-touches. Immediately all Rome flocked to see it, the Pope being

the first, arriving before the dust of the scaffolding had been removed. Raphael,

who was excellent in imitating, at once changed his style after seeing it, and

to show his skill did the prophets and sybils in the church of Santa Maria della

Pace, while Bramante tried to have the other half of the chapel given to Raphael.

On hearing this Michelangelo

became incensed against Bramante, and pointed out to the Pope without mincing

matters many faults in his life and works, the latter of which he afterwards

corrected in the building of S. Pietro. But the Pope daily became more convinced

of Michelangelo's genius, and wished him to complete the work, judging that

he would do the other half even better. Thus, singlehanded, he completed the

work in twenty months, aided by his mixer of colours. He sometimes complained

that owing to the impatience of the Pope he had not been able to finish it as

be would have desired, as the Pope was always asking him when he would be done.

On one occasion Michelangelo replied that he would be finished when he had satisfied

his own artistic sense. "And we require you to satisfy us in getting it

done quickly," replied the Pope, adding that if it was not done soon he

would have the scaffolding down. Fearing the Pope's impetuosity. Michelangelo

finished what he had to do without devoting enough time to it, and the scaffold

being removed it was opened on All Saints day, when the Pope went there to sing

Mass amid the enthusiasm of the whole city. Like the old masters who had worked

below, Michelangelo wanted to retouch some things a secco, such as the backgrounds,

draperies, the gold ornaments and things, to impart greater richness and a better

appearance. When the Pope learned this he wished it to be done, for he heard

what he had seen so highly praised, but as it would have taken too long to reconstruct

the scaffold it remained as it was. The Pope often saw Michelangelo, and said,

"Have the chapel enriched with colours and gold, in which it is poor."

He would answer familiarly, "Holy Father, in those days they did not wear

gold; they never became very rich, but were holy men who despised wealth."

Altogether Michelangelo received 3000 crowns from the Pope for this work, and

he must have spent twenty-five on the colours. The work was executed in great

discomfort, as Michelangelo had to stand with his head thrown back, and he so

injured his eyesight that for several months he could only read and look at

designs in that posture. I suffered similarly when doing the vaulting of four

large rooms in the palace of Duke Cosimo, and I should never have finished them

had I not made a seat supporting the head, which enabled me to work lying down,

but it so enfeebled my head and injured my sight that I feel the effects still,

and I marvel that Michelangelo supported the discomfort. However, he became

more eager every day to be doing and making progress, and so he felt no fatigue,

and despised the discomfort.

The work had six corbels

on each side and one at each end, containing sibyls and prophets, six braccia

high, with the Creation of the World in the middle, down to the Flood and Noah's

drunkenness, and tlie generations of Jesus Christ in the lunettes. He used no

perspective or foreshortening, or any fixed point of view, devoting his energies

rather to adapting the figures to the disposition than the disposition to the

figures, contenting himself with the perfection of his nude and draped figures,

which are of unsurpassed design and excellence. This work has been a veritable

beacon to our art, illuminating all painting and the world which had remained

in darkness for so any centuries. Indeed, painters no longer care about novelties,

inventions, attitudes and draperies, methods of new expression or striking subjects

painted in different ways, because this work contains every perfection that

can be given. Men are stupefied by the excellence of the figures, the perfection

of the foreshortening, the stupendous rotundity of the contours, the grace and

slenderness and the charming proportions of the fine nudes showing every perfection;

every age, expression and form being repre- sented in varied attitudes, such

as sitting, turning, holding festoons of oak-leaves and laurel, the device of

Pope Julius, showing that his was a golden age, for Italy had yet to experience

her miseries. Some in the middle hold medals with, scenes, painted like bronze

or gold, the subject being taken from the Book of Kings. To show the greatness

of God and the perfection of art  he represents the Dividing of Light from Darkness,

showing with love and art the Almighty, self-supported, with extended arms.

With fine discretion and ingenuity he then did God maknig the sun and moon,

supported by numerous cherubs, with marvellous foreshortening of the arms and

legs. The same scene contains the blessing of the earth and the Creation, God

being foreshortened in the act of flying, the figure following you to whatever

part of the chapel you turn. In another part he did God dividing the waters

from the land, marvellous figures showing the highest intellect and worthy of

being made by the divine hand of Michelangelo.

he represents the Dividing of Light from Darkness,

showing with love and art the Almighty, self-supported, with extended arms.

With fine discretion and ingenuity he then did God maknig the sun and moon,

supported by numerous cherubs, with marvellous foreshortening of the arms and

legs. The same scene contains the blessing of the earth and the Creation, God

being foreshortened in the act of flying, the figure following you to whatever

part of the chapel you turn. In another part he did God dividing the waters

from the land, marvellous figures showing the highest intellect and worthy of

being made by the divine hand of Michelangelo.  He

continued with the creation of Adam, God being borne by a group of little angels,

wlio seem also to be supporting the whole weight of the world. The venerable

majesty of God with the motion as He surrounds some of cherubs with one arm

and stretches the other to an Adam of marvellous beauty of attitude and outline,

seem a new creation of the Maker rather than one of the brush and design of

such a man. He next did the creation of our mother Eve, showing two nudes, one

in a heavy sleep like death, the other quickened by the blessing of God. The

brush of this great artist has clearly marked the difference between sleeping

and waking, and the firmness presented by the Divine Majesty, to speak humanly.

He

continued with the creation of Adam, God being borne by a group of little angels,

wlio seem also to be supporting the whole weight of the world. The venerable

majesty of God with the motion as He surrounds some of cherubs with one arm

and stretches the other to an Adam of marvellous beauty of attitude and outline,

seem a new creation of the Maker rather than one of the brush and design of

such a man. He next did the creation of our mother Eve, showing two nudes, one

in a heavy sleep like death, the other quickened by the blessing of God. The

brush of this great artist has clearly marked the difference between sleeping

and waking, and the firmness presented by the Divine Majesty, to speak humanly.

He

then did Adam eating the apple, persuaded by a figure half woman and half serpent,

and he and Eve expelled from Paradise, the angel executing the order of the

incensed Deity with grandeur and nobility, Adam showing at once grief for his

sin and the fear of death, while the woman displays shame, timidity and a desire

to obtain pardon as she clasps her arms and hands over her breast, showing,

in turning her head towards the angel, that she has more fear of the justice

than hope of the Divine mercy. No less beautiful is the sacrifice of Cain and

Abel, one bringing wood, one bending over the fire, and some killing the victim,

certaiffly not executed with less thought and care than the others. He employed

a like art and judgment in the story of the Flood, containing various forms

of death, the terrified men trying every possible means to save their lives.

Their heads show that they recognise the danger with their terror and utter

despair. Some are humanely assisting each other to climb to the top of a rock;

one of them is trying to remove a half-dead man in a very natural manner. It

is impossible to describe the excellent treatment of Noah's drunkenness, showing

incomparable and unsurpassable art. Encouraged by these he attacked the five

sibyls and seven prophets, showing himself even greater. They are of five braccia

and more, in varied attitudes, beautiful draperies and displaying miraculous

judgment and invention, their expressions seeming divine to a discerning eye.

He

then did Adam eating the apple, persuaded by a figure half woman and half serpent,

and he and Eve expelled from Paradise, the angel executing the order of the

incensed Deity with grandeur and nobility, Adam showing at once grief for his

sin and the fear of death, while the woman displays shame, timidity and a desire

to obtain pardon as she clasps her arms and hands over her breast, showing,

in turning her head towards the angel, that she has more fear of the justice

than hope of the Divine mercy. No less beautiful is the sacrifice of Cain and

Abel, one bringing wood, one bending over the fire, and some killing the victim,

certaiffly not executed with less thought and care than the others. He employed

a like art and judgment in the story of the Flood, containing various forms

of death, the terrified men trying every possible means to save their lives.

Their heads show that they recognise the danger with their terror and utter

despair. Some are humanely assisting each other to climb to the top of a rock;

one of them is trying to remove a half-dead man in a very natural manner. It

is impossible to describe the excellent treatment of Noah's drunkenness, showing

incomparable and unsurpassable art. Encouraged by these he attacked the five

sibyls and seven prophets, showing himself even greater. They are of five braccia

and more, in varied attitudes, beautiful draperies and displaying miraculous

judgment and invention, their expressions seeming divine to a discerning eye. Jeremiah, with crossed legs, holds his beard with his elbow on his knee, the

other hand resting in his lap, and his head being bent in a melancholy and thoughtful

manner, expressive of his grief, regrets, reflection, and the bitterness he

feels concerning his people. Two boys behind him show similar power; and in

the first sibyl nearer the door, in representing old age, in addition to the

involved folds of her draperies, he wishes to show that her blood is frozen

by time, and in reading she holds the book close to her eyes, her sight having

failed. Next comes

Jeremiah, with crossed legs, holds his beard with his elbow on his knee, the

other hand resting in his lap, and his head being bent in a melancholy and thoughtful

manner, expressive of his grief, regrets, reflection, and the bitterness he

feels concerning his people. Two boys behind him show similar power; and in

the first sibyl nearer the door, in representing old age, in addition to the

involved folds of her draperies, he wishes to show that her blood is frozen

by time, and in reading she holds the book close to her eyes, her sight having

failed. Next comes  Ezekiel,

an old man with fine grace and movement, in copious draperies, one hand holding

a scroll of his prophecies, the other raised and his head turned as if he wished

to declare things high and great. Behind him are two boys holding his books.

Next comes a sibyl, who, unlike the

Ezekiel,

an old man with fine grace and movement, in copious draperies, one hand holding

a scroll of his prophecies, the other raised and his head turned as if he wished

to declare things high and great. Behind him are two boys holding his books.

Next comes a sibyl, who, unlike the  Erethrian

sibyl just mentioned, holds her book at a distance, and is about to turn the

page; her legs are crossed, and she is reflecting what she shall write, while

a boy behind her is lighting her lamp. This figure has an expression of extraordinary

beauty, the hair and draperies are equally fine, and her arms are bare, and

as perfect as the other parts. He did next the Joel earnestly reading a scroll,

with the most natural expression of satisfaction at what he finds written, exactly

like one who has devoted close attention to some subject. Over the door of the

chapel Michelangelo placed the aged

Erethrian

sibyl just mentioned, holds her book at a distance, and is about to turn the

page; her legs are crossed, and she is reflecting what she shall write, while

a boy behind her is lighting her lamp. This figure has an expression of extraordinary

beauty, the hair and draperies are equally fine, and her arms are bare, and

as perfect as the other parts. He did next the Joel earnestly reading a scroll,

with the most natural expression of satisfaction at what he finds written, exactly

like one who has devoted close attention to some subject. Over the door of the

chapel Michelangelo placed the aged  Zachariah,

who is searching for something in a book, with one leg raised and the other

down, though in his eager search he does not feel the discomfort. He is a fine

figure of old age somewhat stout in person, his fine drapery falling in few

folds. There is another sibyl turned towards the altar showing writings, not

less admirable with her I" boys than the others. But for Nature herself

one must see the

Zachariah,

who is searching for something in a book, with one leg raised and the other

down, though in his eager search he does not feel the discomfort. He is a fine

figure of old age somewhat stout in person, his fine drapery falling in few

folds. There is another sibyl turned towards the altar showing writings, not

less admirable with her I" boys than the others. But for Nature herself

one must see the  Isaiah,

a figure wrapped in thought, with his legs crossed, one hand on his book to

keep the place, and the elbow of the other arm also on the volume, and his chin

in his hand. Being called by one of the boys behind, he rapidly turns his head

without moving the rest of his body. This figure, when well studied, is a liberal

education in all the principles of painting.

Isaiah,

a figure wrapped in thought, with his legs crossed, one hand on his book to

keep the place, and the elbow of the other arm also on the volume, and his chin

in his hand. Being called by one of the boys behind, he rapidly turns his head

without moving the rest of his body. This figure, when well studied, is a liberal

education in all the principles of painting.

Next to him is a beautiful

aged sibyl who sits studying a book, with extraordinary grace, matched by

the

two boys beside her. It would not be possible to add to the excellence of the

youthful Daniel, who is writing in a large book, copying with incredible

eagerness

from some writings, while a boy standing between his legs supports the weight

as he writes. Equally beautiful is the Lybica, who, having written a large

volume

drawn from several books, remains in a feminine attitude ready to rise and

shut the book, a difficult thing practically impossible for any other master.

What

can I say of the four scenes in the angles of the corbels of the vaulting?  A

David stands with his boyish strength triumphant over a giant, gripping him

by the neck while soldiers about the camp marvel. Very wonderful are the attitudes

in the story of Judith, in which we see the headless trunk of Holofernes,

while

Judith puts the head into a basket carried by her old attendant, who being

tall bends down to permit Judith to do it, while she prepares to cover it,

and turning

towards the trunk shows her fear of the camp and of the body, a well-thoughtout

painting. Finer than this and than all the rest is the story of the

A

David stands with his boyish strength triumphant over a giant, gripping him

by the neck while soldiers about the camp marvel. Very wonderful are the attitudes

in the story of Judith, in which we see the headless trunk of Holofernes,

while

Judith puts the head into a basket carried by her old attendant, who being

tall bends down to permit Judith to do it, while she prepares to cover it,

and turning

towards the trunk shows her fear of the camp and of the body, a well-thoughtout

painting. Finer than this and than all the rest is the story of the Brazen Serpent, over the left corner of the altar, showing the death of many,

the biting of the serpents, and Moses raising the brazen serpent on a staff,

with a variety in the manner of death and in those who being bitten have lost

all hope. The keen poison causes the agony and death of many, who lie still

with twisted legs and arms, while many fine heads are crying out in despair.

Not less beautiful are those regarding the serpent, who feel their pains diminishing

with returning life. Among them is a woman, supported by one whose aid is as

finely shown as her need in her fear and distress. The scene of Ahasuerus

in

bed having the annals read to him is very fine. There are three figures eating

at a table, showing the council held to liberate the Hebrews and impale Haaman,

a wonderfully foreshortened figure, the stake supporting him and an arm stretched

out seerifing real, not painted, as do his projecting leg and the parts of

the

body turned inward. It would take too long to enumerate all the beauties and

various circumstances in the genealogy of the patriarchs, beginning with the

sons of Noah, forming the generation of Christ, containing a great variety

of draperies, expressions, extraordinary and novel fancies; nothing in fact

but

displays genius, all the figures being finely foreshortened, and everything

being admirable and divine. But who can see without wonder and amazement the

tremendous Jonah, the last figure of the chapel, for the vaulting which curves

forward from the wall is made by a triumph of art to appear straight, through

the posture of the figure, which by the mastery of the drawing and the light

and shade, appears really to be bending backwards. O, happy age O, blessed

artists

who have been able to refresh your darkened eyes at the fount of such clearness,

and see difficulties made plain by this marvellous artist! His labours have

removed the bandage from your eyes, and he has separated the true from the

false which clouded the mind. Thank Heaven, then, and try to imitate Michelangelo

in all things.

Brazen Serpent, over the left corner of the altar, showing the death of many,

the biting of the serpents, and Moses raising the brazen serpent on a staff,

with a variety in the manner of death and in those who being bitten have lost

all hope. The keen poison causes the agony and death of many, who lie still

with twisted legs and arms, while many fine heads are crying out in despair.

Not less beautiful are those regarding the serpent, who feel their pains diminishing

with returning life. Among them is a woman, supported by one whose aid is as

finely shown as her need in her fear and distress. The scene of Ahasuerus

in

bed having the annals read to him is very fine. There are three figures eating

at a table, showing the council held to liberate the Hebrews and impale Haaman,

a wonderfully foreshortened figure, the stake supporting him and an arm stretched

out seerifing real, not painted, as do his projecting leg and the parts of

the

body turned inward. It would take too long to enumerate all the beauties and

various circumstances in the genealogy of the patriarchs, beginning with the

sons of Noah, forming the generation of Christ, containing a great variety

of draperies, expressions, extraordinary and novel fancies; nothing in fact

but

displays genius, all the figures being finely foreshortened, and everything

being admirable and divine. But who can see without wonder and amazement the

tremendous Jonah, the last figure of the chapel, for the vaulting which curves

forward from the wall is made by a triumph of art to appear straight, through

the posture of the figure, which by the mastery of the drawing and the light

and shade, appears really to be bending backwards. O, happy age O, blessed

artists

who have been able to refresh your darkened eyes at the fount of such clearness,

and see difficulties made plain by this marvellous artist! His labours have

removed the bandage from your eyes, and he has separated the true from the

false which clouded the mind. Thank Heaven, then, and try to imitate Michelangelo

in all things.

When the work was uncovered

everyone rushed to see it from every part and remained dumbfounded. The Pope,

being thus encouraged to greater designs, richly rewarded Michelangelo, who

sometimes said in speaking of the great favours showered upon him by the Pope

that he fully recognised his powers, and if he sometimes used hard words, he

healed them by signal gifts and favours. Thus, when Michelangelo once asked

leave to go and spend the feast of St. John in Florence, and requested money

for this, the Pope said, "When will this chapel be ready?" "When

I can get it done, Holy Father." The Pope struck him with his mace, repeating,

"When I can, when I can, I will make you finish it !" Michelangelo,

however, returned to his house to prepare for his journey to Florence, when

the Pope sent Cursio, his chamberlain, with five hundred crowns to appease him

and excuse the Pope, who feared what Michelangelo might do. As Michelangelo

knew the Pope, and was really devoted to him, he laughed, especially as such