Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments | ARTH 220 Syllabus

Excerpts from

Patricia Simons, "Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture"

from History Workshop: A Journal of Socialist and Feminist Historians, 25 (Spring, 1988), 4-30; reprinted in Broude and Garrard, The Expanding Discourse, pp.38-57:

p. 39: Studies of Renaissance art have had difficulty in accomodating contemporary thinking on sexuality and feminism. The period which is presumed to have witnessed the birth of Modern Man and the discovery of the World does not seem to require investigation. Renaissance art is seen as a naturalistic reflection of a newly discovered reality, rather than as a set of framed myths and gender-based constructions. In its stature as high culture, it tends to be either applauded or ignored (by the political right or left respectively) as an untouchable, elite production. My work on profile portraits of Florentine women attempts to bring theories of the gaze to bear on some of these traditional Master theories, thereby unmasking the apparent inevitability and neutrality of Renaissance art.

Around forty independent panel portraits of women in profile survive from Quattrocento Tuscany, but it is thought that this genre began in Italy around the years 1425-50 with a cluster of five male portraits. The only extended discussions of the Renaissance profile convention tend to presume a male norm for all surviving panels. Jean Lipman in 1936 wrote of the female figures' "bulk and weight" and "strong shapes," Rab Hatfield's study on the five male profiles of their "bravura" and "strong shapes." Both writers were imbued by Jakob Burckhardt's interpretation of the Renaissance as a period giving birth to modern, individualistic man. For the art historian specifically, the rise of an individualistic consciousness during the Renaissance, plotted by Burckhardt in 1860, explains the development of individualized and more numerous portraiture at the time. Hence for Lipman these figures --"completely exposed to the gaze of the spectator"-- were self-sufficient, invulnerable, displaying by the surface emphasis of the design only the surface of the self-contained person. Hatfield's later attention to social context shifted the emphasis, for he argued that "intimacy is deflected" because "social prestige" is being celebrated and a family "pedigree" formed in the images. But the portrayed were characterized by their visual order as reasoned, intelligent men whose virtù , or public and moral virtue, required "admiration and respect." For both writers, the profile portrait celebrates fame, and derives from public pictorial conventions....

/p. 40: Usually, the utilization of the profile in fifteenth-century art is explained by recourse to the revival of the classical medal and the importation of conventions for the portrayal of courtly rulers, evoking the celebration of fame and individualism. Such causal reasoning is inappropriate to the parameters and frames of Quattrocento women. In this paper, profile portraits will be viewed as constructions of gender conventions, not as natural, neutral images.

Behind this project lies a late-twentieth century interest in the eye and the gaze, largely investigated so far in terms of psychoanalysis and film theory. Further, various streams of literary criticism and theory make us aware of the construction of myths and images, of the degree to which the reader (and the viewer) are active, so that, in ethnographic terms, the eye is a performing agent. Finally, feminism can be brought to bear on a field and a discipline which are only beginning to adjust to a de-Naturalized, post-humanist world. Burckhardt again looms here, for he believed that "women stood on a footing of perfect equality with men" in the Italian Renaissance, since "the educated woman, no less than the man, strove naturally after a characteristic and complete individuality." That the "education given to women in the upper classes, was essentially the same as that given to men" is neither true, we would say, nor adequate proof of their social equality.

Joan Kelly's essay of 1977, "Did Women Have a Renaissance?," opened a debate amongst historians of literature, religion and society, but art historians have been slower to enter the discussion. A patriarchal historiography which sees the Renaissance as the Beginning of Modernism continues to dominate art history, and studies of Renaissance painting are little touched by the feminist enterprise. Whilst images of or for women are now beginning to be treated as a category, some of this work perpetuates women's isolation in a separate sphere and takes little account of gender analysis. Instead, we can examine relationships between the sexes and think of gender as "a primary field with which or by means of which power is articulated." So we need to consider the visual /p. 41: construction of sexual difference and how men and women were able to operate as viewers. Further, attention can be paid to the visual specifics of form rather than content or "iconography," so that theory can be related to practice.

The body of this paper investigates the gaze in the display culture of Quattrocento Florence to explicate further ways in which the profile, presenting as averted eye and a face available to scrutiny, was suited to the representation of an ordered, chaste and decorous piece of property....

The history of the profile to ca. 1440 was a male history, except for the occasional inclusion of women in altarpieces as donor portraits, that is, portraits of those making their pious offering to the almighty. But from ca. 1440 nearly all Florentine painted profile portraits depicting a single figure are of women (except for a few studies of male heads on paper, probably sketches for medals and sculpture when they are portraits and not studio exercises). By ca. 1450 the male was shown in three-quarter length and view, first perhaps in Andrea Castagno's sturdy view of an unknown man whose gaze, hand and facial structure intrude through the frame into the viewer's space....

For some time, however, women were still predominantly restricted to the profile, and most examples of this format are dated after mid-century. Only in the later 1470's do portraits of women once more follow conventions for the male counterparts, moving out from the restraining control of the profile format, turning towards the viewer and tending to be views of women both older and less ostentatiously dressed than their female predecessors had been. Such a change has not been investigated and cannot be my subject here, which is to highlight the predominance of a female presence in Florentine profile portraits.

Painted by male artists for male patrons, these objects primarily addressed male viewers. Necessarily members of the ruling and wealthy class in patrician Florence, the patrons held restrictive notions of proper female behavior for women of their class. Elsewhere in Italy, especially in the northern courts, princesses were also restrained by rules of female decorum but were portrayed because they were noble, exceptional women. In mercantile Florence, however, that women who were not royal were recognized in portraiture at all appears puzzling, and I think can only be understood in terms of the visual or optic modes of what can be called a "display culture." By this I mean a culture where the outward display of honor, magnificence and wealth was vital to one's social prestige and definition, so that visual language was a crucial mode of discourse....

To be a woman in the world was /is to be the object of the male gaze: to "appear in public" is "to be looked upon," wrote Giovanni Boccaccio. The Dominican nun Clare Gambacorta (d. 1419) wished to avoid such scrutiny and establish a convent "beyond the gaze of men and free from worldly distractions." The gaze, then a metaphor for worldliness and virility, made of Renaissance woman an object of public discourse, / p. 42: exposed to scrutiny and framed by parameters of propriety, display, and "impression management." Put simply, why else paint a woman except as an object of display within male discourse?

Only at certain key moments could she be seen, whether at a window or in the "window" of a panel painting, seen and thereby represented. These centered on her rite of passage from one male house to another upon her marriage, usually at an age between fifteen and twenty, to a man as much as fifteen years her senior. Her very existence and definition at this time was a function of her outward appearance. Pleading for extra finery and household linen, rather than merely functional clothing, to be included in her dowry, one widow implored her children, when her brothers forced her into a second marriage, "Give me a way to be dressed." This woman virtually pictures herself as naked and undefined unless a certain level (modo) of (ad)dress or representation as will as wealth can be attained. Costume was what Diane Owen Hughes calles "a metaphorical mode" for social distinction and regulation. The "emblematic significance" of dress made possible the visible marking out of one's parental and marital identity. A bearer of her natal inheritance and an emblem also of her conjugal line once she had entered the latter's boundaries, a woman was an adorned Other who was defined into existence when she entered patriarchal discourse primarily as an object of exchange.

Without what Christiane Klapisch-Zuber calls "publicity," the important alliance forged between two households or lineages by a marriage was not adequately established. Without witnesses, the contract was not finalized. By contrast, the priest's presence at this time was not legally necessary. Visual display was an essential component of the ritual, a performance which allowed, indeed expected, a woman's visible presentation in social display and required an appropriately honorable degree of adornment.

The age of the women in these profile portraits, along with the lavish presence of jewelry and fine costumes (usually outlawed by sumptuary legislation and rules of morality and decorum), with multiple rings on her fingers when her hands are shown, and hair bound rather than free-flowing, are all visible signs of her newly married (or perhaps sometimes betrothed) state. The woman was a spectacle when she was an object of public display at the time of her marriage but otherwise she was rarely visible, whether on the streets or in monumental works of art. In panels displayed in areas of the palace open to common interchange, she was portrayed as a sign of the ritual's performance, the alliance's formation and its honorable nature.

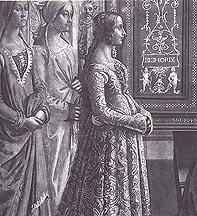

An example of a father's attention to his daughter before marriage, however, also points up attitudes taken to a woman's public appearance. Whilst Giovanni Tournabuoni granted jewelry to his daughter Ludovica as part of her lavish dowry, he will of 1490 nevertheless stipulated that two of the valuable, carefully described items ultimately remain part of his male patrimony, for they were to return to his estate upon her decease. A cross surrounded by pearls, probably the "crocettina" mentioned in Giovanni's will, hangs from Ludovica's neck in her portrait by Domenico Ghirlandaio within the family chapel at Santa Maria Novella, decorated at her father's expense between 1486 and 1490. She also wears a dress richly brocaded with the triangular Tornabuoni emblem. So, at the time when she was betrothed but not yet married, not long before she passed beyond their confines, she is displayed forever as a Tornabuoni woman, wearing their emblem and wealth.

Ludovica

is also represented as a virginal Tornabouni exemplar, attendant at the Birth

of the Virgin and with her hair still hanging loose, as it had in

her earlier medal, where a unicorn on the reverse again emphasized her honorable

virginity. In the chapel fresco Ludovica is presented as the perfect bride-to-be,

from a noble and substantial family, about to become a child-bearing woman.

Her father's solicitude and family pride oversaw the construction of a public

image declaring her value and thereby increasing Tornabuoni honor. Soon her

husband will conduct her on her rite of passage, collect his dowry and appropriate

her honor to the needs of his lineage.

Ludovica

is also represented as a virginal Tornabouni exemplar, attendant at the Birth

of the Virgin and with her hair still hanging loose, as it had in

her earlier medal, where a unicorn on the reverse again emphasized her honorable

virginity. In the chapel fresco Ludovica is presented as the perfect bride-to-be,

from a noble and substantial family, about to become a child-bearing woman.

Her father's solicitude and family pride oversaw the construction of a public

image declaring her value and thereby increasing Tornabuoni honor. Soon her

husband will conduct her on her rite of passage, collect his dowry and appropriate

her honor to the needs of his lineage.

/p. 43: When the bride went fuori ('outside') and was "led" or "taken away" by her husband, she bore a counter-dowry of goods supplied by him. One mother, Alessandra Strozzi, happily reported her daughter in 1447 that "When she goes out of the house, she'll have more than 400 florins on her back" because the groom Marco Parenti "is never satisfied having things made for her, for she is beautiful and he wants her to look at her best...."

In wanting his bride "to look at her best" Marco was seeking a visible, displayable sign of his honor. Indeed a wife's costume was considered by jurists a sign of her husband's rank. "Being beautiful and belonging to Filippo Strozzi," Alessandra wrote to her son of a potential bride in 1465, " she must have beautiful jewels, for just as you have won honor in many things, you can not fall short in this." Like the "golden facade" of a palace, "such adornments...are taken as evidence of the wealth of the husband more than as a desire to impress wanton eyes," wrote Francesco Barbaro in his treatise On Wifely Duties of 1416. To Barbaro, a wife's public appearance was a sign of her propriety and her husband's trust: wives "should not be shut up in their bedrooms as in a prison but should be permitted to go out [in apertum], and this privilege should be taken as evidence of their virtue and probity."

He then went

on, "By maintaining a decorous and honest gaze in their eyes, the most

acute of senses, they can communicate as in painting, which is called silent

poetry...." Attributes of costume, jewelry and honorable bearing are

as much signs as the occasional coats of arms in these portraits.  And

in Florence, these heraldic devices are the husband's, for the woman has been

renamed and inscribed into a new lineage. Hence in Filippo Lippi's Portrait

of a Man and Woman at a Casement, the Scolari man's coat of arms is matched

not by her own natal heraldry but by her motto, embroidered in his pearls

on the sleeve she has been given, which avows "Loyalty" to him.

And

in Florence, these heraldic devices are the husband's, for the woman has been

renamed and inscribed into a new lineage. Hence in Filippo Lippi's Portrait

of a Man and Woman at a Casement, the Scolari man's coat of arms is matched

not by her own natal heraldry but by her motto, embroidered in his pearls

on the sleeve she has been given, which avows "Loyalty" to him.

Perhaps we can find an explanation for those numerous donor portraits in profile by considering the...linkage, by the nun Clare Gambacorta, between "the gaze of men" and "worldly distractions." Particularly when shown in profile, the donor's faces are visible to both divine and "worldly," sacred and "secular" (yet sacralized) realms, seen by the adored sanctities yet also viewed by priests and devotees, including the donors themselves. Like nuns and donors /p. 44: the women portrayed in profile are displayed and visible objects, and yet they are removed from "worldly distractions." They are inactive objects gazing elsewhere, decorously averting their eyes. In this sense they are chaste, if not virginal, framed if not (quite) cloistered. However, unlike nuns, these idealized women are very much not "beyond the gaze of men."

A young Florentine patrician girl rarely became anything other than a nun or a wife. In each instance she was defined in relation to her engagement with men, either marrying Christ or a worldly husband and eschewing all other men....

Visually, the strict orderliness of the profile portrait can be seen as a surprising contradiction of contemporary misogynist literature. Supposedly "inconstant," like "irrational animals" without "any set proportion," living "without order or measure," women are transformed by their "beauty of mind" and "dowry of virtue" into ordered, constant, geometrically proportioned and unchangeable images, bearers of an inheritance which would be "precious" to their children. A woman, who was supposedly vain and narcissistic, was nevertheless made an object in a framed "mirror" when a man's worldly wealth and her ideal dowry, rather than her "true" or "real" nature, was on display.

Giovanna Tornabouni's portrait by Domenico Ghirlandaio contains an inscription, with the date 1488, indicating that "conduct and soul" were valuable, laudable commodities carried by the woman. Further, depiction strove for the problematic representation of these invisible virtues" "O art, if thou were able to depict the conduct /p. 45: and soul, no lovelier painting would exist on earth." Having died whilst pregnant in 1488, the new dead Giovanna née Albizzi is here immortalized as noble and pious, bearing her husband's initial, L for Ludovico, on her shoulder and his family's simplified, triangular emblem on her garment. She is forever absorbed as part of the Tornabuoni heritage, displayed in their palace to be seen by their visitors and themselves, including her son, who bore their name.

Within the panel, she is framed by a simple, closed-off room; within the palace, we know from an inventory, she was actually framed in a "cornice made of gold" on show in a splendid "room of golden stalls." Sealed in a niche like her accourtrements of piety and propriety, she is an eternally static spectacle held decorously firm by her arm, neck, and spine. Giovanna's very body becomes a sign, attempting to articulate her intangible but valuable "conduct and soul." The "dowry of virtue" is encased and contained within her husband's finery, each enhancing the other. Forever framed in a state of idealized preservation, she is constructed as a female exemplar for Tornabuoni viewers and others they wished to impress with this ornamento.

Profile portraits such as Giovanna's participate in a language of visual and social conventions. They are not simply reflection of a preexistent social or visual reality.... In these portraits a woman can wear cosmetics and extravagant decoration forbidden by legal and moral codes. There this orderly creature was visible at or near a window, yet she was explicitly banished from public appearance at such windows. There a dead wife or absent daughter or newly incorporated, deflowered wife was made an object of commemoration, as eternally alive and chaste....

A woman's painted presence shares with cultural values of the time an idealized stock of impressive, manipulative language available within Quattrocento culture. Visual art, it can be argued, both shared and shaped social language and need not be seen as a passive reflection of predetermining reality. For the representation of women, the profile form and its particulars were well suited to the construction, rather than reflection, of an invisible "reality."

It is not only the display of attributes like jewelry and costume (perhaps often more splendid fantasies than were the actual possessions) which pronounce the portrayed woman as the bearer of "wealth" both earthly and invisible. The profile form itself is amenable to the construction of a display object, since the viewed is rendered static by an impersonal, typifying structure....

Niccolò Fiorentino, Giovanna degli Tornabuoni, c. 1486 Inscription on Obverse: VXOR LAVRENTII DETORNABONIS IONNA ALBIZA (wife of Lorenzo Tornabuoni Giovanna Albizzi) Inscription on the reverse: CASTITAS PVL [CH] RITUDO AMOR (Chastity, Beauty, Love) Giovanna was born in 1468, the daughter of Maso degli Albizzi. Lorenzo Medici arranged the marriage of Giovanna to Lorenzo Tornabuoni, son of Giovanni. The marriage celebrated on June 15, 1486 marked the alliance of two major Florentine families. In October of 1487, Giovanna gave birth to a son, Giovanni, thus fulfilling her dynastic role. She died in child birth in October of 1488. |

/p. 46: "Individuality" appears to the degree that simplifying silhouettes can represent particular faces. But full characterization depends upon facial asymmetry, and momentary moods are also denied by the timeless patterning profile. In these mostly anonymous profile portraits, face and body are as emblematic as coats of arms....

The traditional

immortalizing of a dead man or a male ruler by use of the profile was appropriated

for female representation, yet the form's restrictive capacity was accentuated.

One of the few surviving pairs in which the male and female portraits are

in profile, Piero della Francesca's depiction of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino

couples a ruler with a woman. ![]() B

B![]() ecause

the duke suffered from a battle wound to his right eye he had to be shown

in profile. This necessity is turned to advantage by strong blocks of color

(which are especially balanced either side of the stabilized face), hard virile

silhouette, massive neck and swarthy, modeled flesh. This is contrasted with

a pale, heavily decorated lady who has been plucked, powdered and adorned

into a chaste emblem. On the reverse of her portrait rides the Triumph of

"feminine virtues," on his the Triumph / p. 47: of Fame. Both ruler

and woman are typecast and stand for more than their individual selves, but

the male is constructed as a more active, dominant figure....

ecause

the duke suffered from a battle wound to his right eye he had to be shown

in profile. This necessity is turned to advantage by strong blocks of color

(which are especially balanced either side of the stabilized face), hard virile

silhouette, massive neck and swarthy, modeled flesh. This is contrasted with

a pale, heavily decorated lady who has been plucked, powdered and adorned

into a chaste emblem. On the reverse of her portrait rides the Triumph of

"feminine virtues," on his the Triumph / p. 47: of Fame. Both ruler

and woman are typecast and stand for more than their individual selves, but

the male is constructed as a more active, dominant figure....

/p. 50: In fifteenth-century society, lowered or averted eyes were the sign of a woman's modesty, chastity and obeisance. A loose woman, on the other hand, looked at men in the street. Temptation or a lover were avoided or discouraged if a virtuous woman did not return the gaze.

attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of a Young Man and Young Woman, c. 1490. |

|

These two paintings by Botticelli while they at first seem to conform to the profile portrait convention diverge from this in notable ways. The profiles are not pure, but rather the heads are slightly turned so that you can see a little bit of the far eye. Also in contrast to portraits like Ghirlandaio's portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni, the perfect and highly stylized hair style of the Ghirlandaio has been loosened in these two Botticelli portraits. The Frankfurt panel breaks from the standard convention of the woman facing left. Scholars have generally agreed that while the same person, likely Simonetta Vespucci, is the model for both paintings, that these two are intended to present an ideal of female beauty. Scholars have related these to the tradition of love poetry from Petrarch and the ideas of ideal beauty. Petrarch wrote love poetry dedicated to "Laura." As in the tradition of the courtly love, Laura is unattainable; it is destined to be an unrequited love. This tradition was continued in the poetry of Botticelli's contemporaries like Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494). Poliziano had written a poem entitled La giostra. The poem celebrates a tournament in 1475 in which Giuliano de' Medici received the victor's crown from Simonetta Vespucci. Poliziano's La giostra has been associated with Botticelli's Venus and Mars in the National Gallery in London:

The physiogomy and details of the hair of the Venus figure have striking similarities to the woman in the Frankfurt portrait. The wasps that buzz around the head of Mars in the London panel suggests an association with the Vespucci family which had on its coat of arms wasps (Vespucci in Italian means "little wasps). Simonetta Cattaneo, born in Genoa, married Marco Vespucci in 1468. She died at the age of 23 in April of 1476.

While the Berlin and Frankfurt portraits and the London Venus and Mars are likely based on Simonetta Vespucci, these figures can also be likened to Petrarch's descriptions of his Laura especially with the elaborately curled hair:

| Breeze, blowing that blonde curling hair, stirring it, and being softly stirred in turn, scattering that sweet gold about, then gathering it, in a lovely knot of curls again, you linger around bright eyes whose loving sting pierces me so, till I feel it and weep, and I wander searching for my treasure, like a creature that often shies and kicks: now I seem to find her, now I realise she’s far away, now I’m comforted, now despair, now longing for her, now truly seeing her. Happy air, remain here with your living rays: and you, clear running stream, why can’t I exchange my path for yours? (227: La Canzoniere) |

Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments | ARTH 220 Syllabus