Art Web | Arth

Home | Arth Courses | Arth 110

|ARTH 110 Assignments

| Forward | Back | Contact

ARTH 110

FLEMISH AND SPANISH BAROQUE PAINTING: RUBENS AND VELAZQUEZ

SLIDE LIST 14

|

|

| Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) Rape of the

Daughters of Leucippus, c. 1616-17. |

Bernini, Pluto and Persephone, 1621-22. |

| |

|

| |

Titian, Rape of Europa, 1538. |

|

|

| Rubens, The Toilet of Venus, 1612-15. |

Titian, Venus with a Mirror, 1555.

|

| |

|

| |

Rubens, Judgement of Paris, 1638. |

|

|

| Rubens, Raising of the Cross, 1610. |

Laocoon and his Sons, Greek, 1st c. B.C. |

|

| Rubens, drawing of the Laocoon, c. 1600-1608. |

|

|

| |

Rubens, Descent from the Cross, 1612. |

|

|

| Rubens, Portrait of Suzanne Fourment, c.

1620-25. |

Rubens, Landscape with the Chateau de Steen,

1635. |

|

|

| Velazquez (1599-1660), Adoration of the

Magi, c. 1619. |

Caravaggio, Entombment, c. 1604. |

|

|

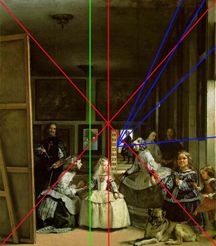

| Velazquez, Las Meninas (Ladies in Waiting), 1656. See webpage discussion |

Detail of Las Meninas. |

|

|

| Velazquez, Philip IV in Brown and Silver, 1631-32. |

|

Question for Review

|

|

| Rubens, Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus,

c. 1616-17. |

Bernini, Pluto and Persephone, 1621-22. |

These are two examples of a large number of other works of the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries that focus on the representation of rape. As works of

culture, these works can be connected to the following quotation from the contemporary

feminist art historian, Griselda Pollock: "Culture is the social level

in which those images of the world and definitions of reality are produced which

can be ideologically mobilized to legitimate the existing order of relations

of domination and subordination between both classes and sexes." Use this

quotation as a critical perspective from which to discuss early modern representations

of rape exemplified by this comparison, and contrast this to contemporary representations

of rape informed by feminism. For the latter part of this discussion, you might

want to consider the high visibility given to legal cases like William Kennedy

Smith rape trial, the Bobbitts' trials, the controversy over Anita Hill and

Clarence Thomas, and of course O.J.

Weblinks

16th and 17th century images of rape have been the focus of several

recent critical studies. Excerpts from an article by Margaret D. Carroll entitled

"The Erotics of Absolutism:

Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence" and excerpts from

the opening chapter from the book by Diane Wolfthal entitled Images

of Rape: the "Heroic" Tradition and its Alternatives explore

this imagery.

Texts

Griselda Pollock, "Vision, Voice and Power: Feminist Art

History and Marxism," in Vision and Difference, p. 20: Culture

can be defined as those social practices whose prime signification,

i.e. the production of sense or making orders of 'sense' for the

world we live in. Culture is the social level in which those images

of the world and definitions of reality are produced which can

be ideologically mobilized to legitimate the existing order of

relations of domination and subordination between both classes

and sexes. Art history takes an aspect of cultural production,

art, as its object of study; but the discipline itself is also

a crucial component of the cultural hegemony by the dominant class

and gender. Therefore it is important to contest the definitions

of our society's ideal reality which are produced in art-historical

interpretations of culture.

Frederick Hartt, Art, 1976, p. 723:[Rubens's] Rape of the

Daughters of Leucippus, of about 1616-17, recalls forcibly

Titian's Rape of Europa, which Rubens carefully copied

while in Spain. Although the figures have been made to fit into

Rubens's mounting spiral, such is the buoyancy of the composition

that the result does not seem artificial. The act of love by which

Castor and Pollux, sons of Jupiter, uplift the mortal maidens

from the ground draws the spectator upward in a mood of rapture

not unrelated to that Bernini was soon to achieve in the Ecstasy

of St. Theresa. The female types, even more abundant than those

of Titian, are traversed by a steady stream of energy, and the

material weight of all the figures is lightened by innumerable

fluctuations of color running through their pearly skin, the tanned

flesh of the men, the armor, the horses, even the floods of golden

hair. The low horizon increases the effect of a heavenly ascension,

natural enough, since this painting ... constitutes a triumph

of divine love; the very landscape heaves and flows in response

to the excitement of the event.

Margaret D. Carroll, "The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification

of Sexual Violence," in The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History,

eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, p. 139: Rubens's Rape of the Daughters

of Leucippus confronts its viewers with an interpretative dilemna. Painted about

1615 to 1618, the life-size composition illustrates the story recounted by Theocritus

and Ovid of how the twin brothers Castor and Pollux (called the Dioscuri) forcibly

abducted and later married the daughters of King Leucippus. Rubens's depiction

of the abduction is marked by some striking ambiguities: an equivocation between

violence and solicitude in the demeanor of the brothers, and an equivocation

between resistance and gratification in the response of the sisters. The spirited

ebullience and sensual appeal of the group work to override our darker reflections

about the coercive nature of the abduction. For these reasons many viewers have

wanted to discount the predatory violence of the brothers' act and to interpret

the painting in a benign spirit, perhaps as a Neoplatonic allegory of the progress

of the soul toward heaven, or as an allegory of marriage. Although I agree that

a reference to marriage may be at play here, I also believe that any interpretation

of the painting is inadequate that does not attempt to come to terms with it

as a celebratory depiction of sexual violence and the forcible subjugation of

women by men....

...[O]ne art historian...[concludes] that Rubens is celebrating the triumph

of natural impulse over conventional inhibition: "The battle of the sexes

is a necessity of nature. With Rubens it is a primal impulse of life, a fight

for unification.....In being raped Pheobe discovers her destiny as a woman.

Her rape reveals and enhances her nature." In claiming something like a

truth value for Rubens's celebratory depiction of this rape, this scholar mystifies

it in terms of a misguided notion of what is natural in human sexuality. My

point is that we must consider Rubens's painting not as a revelation of primal

human nature but as a phenomenon of sixteenth- and seventeenth- century European

culture. In particular we may view Rubens's painting as issuing from a tradition

that emerged among princely patrons at the time, of incorporating large-scale

mythological rape scenes into their palace decorations. With fundamental shifts

in political thinking and experience in early sixteenth-century Europe, princes

came to appreciate the particular luster rape scenes could give to their own

claims to absolute sovereignty....

Details of Las

Meninas

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rubens, Apollo

and Marsyas.

|

Rubens, Minerva

and Arachne.

|

Art Web | Arth

Home | Arth Courses | Arth 110

|ARTH 110 Assignments

| Forward | Back | Contact