Arth Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments

Vanity

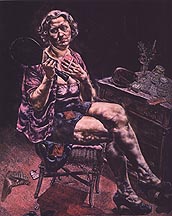

Ivan Albright, Into the World Came a Soul Called Ida (the Lord in His Heaven and I in my Room Below), 1929-30.

Vanity: 1. The quality or condition of being vain; excessive pride in one's appearance or accomplishments; conceit; 2. Lack of usefulness, worth, or effect; hollowness; futility; worthlessness. 3a. Something that is vain, futile, or worthless. b. Something about which one is vain or conceited. 4. A vanity case. 5. a dressing table (see)... (American Heritage Dictionary)

Excerpt from Susan S. Weininger, "Ivan Albright in Context," in Ivan Albright, organized by Courtney Graham Donnell, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1997: p. 61: Albright and the Vanitas Theme: The vanitas, or memento mori, theme --a moralizing reminder that life's pleasures are momentary and that death is inevitable -- originated in northern Europe in the late Middle Ages and continued to preoccupy painters into the eighteenth century. The subject allowed artists to indulge in seductive representations of these pleasures and then to subvert the seduction through various moralizing touches. The painter of a vanitas composition could draw upon a wide vocabulary of symbols, used alone or in a variety of combinations, to suggest the transience of the material world. These could include a beautiful woman regarding herself in a mirror; arrangements of fruit and/or flesh flowers (whose life spam, from bud to perfumed fullness to withered end, occurs in a matter of days); the butterfly (indicating the escape of the soul from the prison of the body); objects of earthly knowledge (books and scientific instruments); references to sinful behavior (musical instruments, liquor, playing cards, dice); luxury items; and a human skull or skeleton....

Albright's entire oeuvre can be viewed as a twentieth-century

exploration of the vanitas in which he pondered the connection between

the physical and spiritual and the relationship of growth and decay, time

and space, the finite and the infinite. Among his most powerful statements

of these theme is Into the World There Came a Soul Called Ida .

A comparison of Ida and Portrait of Artist Hans Burgkmair and

His Wife, Anna

.

A comparison of Ida and Portrait of Artist Hans Burgkmair and

His Wife, Anna  by Laux (Lucas) Furtenagel, a sixteenth-century German painter, provides

instructive insights into the meaning of Albright's haunting composition.

In the Renaissance painting, a man and a woman confront their skeletal reflections

in a large mirror held by the woman. Her express --one of sadness and desperation--

is not dissimilar to that of Ida. Like Albright's unforgettable female character,

Burgkmair's wife is dressed in a fairly revealing garment and wears no head

covering, indicating a level of intimacy with the viewer. The paintings

share a somber palette, the use of strong chiaroscuro, and a careful rendering

of form and textures. In addition to his searing characterization of Ida,

a woman fully aware of the passage of time and of the inevitability of loss,

Albright included a number of allusions to the fleeting nature of matter.

The vase with dying flowers, the money on the dressing-table top, and the

comb and powder puff that Ida uses in vain to obliterate signs of her physical

decline all reinforce the feeling of an inexorable and irreversible process

at work. Furtenagel's painting assumes a theological framework in which

the decay of matter is contrasted with the eternal life of the spirit in

the hereafter. Albright's image, on the other hand, does not posit everlasting

life. Its pathos is located in the purely human dilemna it depicts. In 1960

the artist explained his interest in death and decay by asserting their

legitimacy: "In

any part of life you find something either growing or disintegrating. /p.

62 All life is strong and powerful, even in the process of dissolution.

For me, beauty is a word without real meaning. But strength and power --they're

what I'm after." In the poignancy and silent fortitude of Ida, Albright

realized an image whose resonance and impact meet the challenge he set

for himself.

by Laux (Lucas) Furtenagel, a sixteenth-century German painter, provides

instructive insights into the meaning of Albright's haunting composition.

In the Renaissance painting, a man and a woman confront their skeletal reflections

in a large mirror held by the woman. Her express --one of sadness and desperation--

is not dissimilar to that of Ida. Like Albright's unforgettable female character,

Burgkmair's wife is dressed in a fairly revealing garment and wears no head

covering, indicating a level of intimacy with the viewer. The paintings

share a somber palette, the use of strong chiaroscuro, and a careful rendering

of form and textures. In addition to his searing characterization of Ida,

a woman fully aware of the passage of time and of the inevitability of loss,

Albright included a number of allusions to the fleeting nature of matter.

The vase with dying flowers, the money on the dressing-table top, and the

comb and powder puff that Ida uses in vain to obliterate signs of her physical

decline all reinforce the feeling of an inexorable and irreversible process

at work. Furtenagel's painting assumes a theological framework in which

the decay of matter is contrasted with the eternal life of the spirit in

the hereafter. Albright's image, on the other hand, does not posit everlasting

life. Its pathos is located in the purely human dilemna it depicts. In 1960

the artist explained his interest in death and decay by asserting their

legitimacy: "In

any part of life you find something either growing or disintegrating. /p.

62 All life is strong and powerful, even in the process of dissolution.

For me, beauty is a word without real meaning. But strength and power --they're

what I'm after." In the poignancy and silent fortitude of Ida, Albright

realized an image whose resonance and impact meet the challenge he set

for himself.

Hans Baldung Grien, Three Ages of Woman and Death (Allegory of Earthly Vanity), 1509-11.

Return to Social Construction of Gender Page.