ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments

From Snake Goddess to Medusa

One of the most intriguing archaeological finds in the remains of the Minoan palace at Knossos was the figure above which has been traditionally identified as the "Snake Goddess." Minoan culture flourished in the middle of the second millenium BCE. It was a palace culture that was focused on the Aegean islands, especially the island of Crete. The culture is named after the legendary King Minos who ruled Crete. The legend of King Minos and the Minotaur were very popular in the historical period of Greek history after the eighth century BCE. Like other legends there is a kernel of truth with its reference to the wealth of the Cretan king, but it is largely a fabrication of the later period. While the Minoans had writing, it was largely for book keeping and there is no literature that comes from this period. So when an object like this faience object was uncovered, we are left to speculate on its meaning. While traditionally called a Snake Goddess, we have no certainty that this is a god or a priestess. How do we understand this figure with its powerful hypnotic stare? While it is not certain that the feline creature on the head was original, the figure is shown brandishing snakes in her hands. Consider the significance of these symbols in later Western culture, especially the symbol of the snake. Christopher Witcombe has dedicated a valuable web site to a discussion of this image. Review this site and write in your journal a statement of what you make of this image.

Medusa and Perseus

| Painted terra-cotta tiles, probably metopes, from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon, from around 630 BCE. The one on the left shows Perseus carrying the head of Medusa while the right one shows the face of Medusa. | ||

The seventh century witnesses the birth of narrative art in Greek art. Artists in a variety of media begin to tell stories in their art. As exemplified by the examples above, one of the most popular stories told by these artists is the story of the Greek hero Perseus, with the aid of the goddess Athena, beheading the monstrous female figure of Medusa. You can read the Wikipedia account of this legend or this other page. Significantly scholars have seen the name Medusa etymologically going back to the Sanscrit name Medha or in Greek Metis or in Egyptian Maat, meaning"sovereign female wisdom." Versions of the story talk about how Medusa was born a beautiful maiden with beautiful flowing hair. She was punished by the goddess Athena for rivalling her beauty and Medusa was transformed into a hideous figure with snakes instead of flowing locks for her hair.

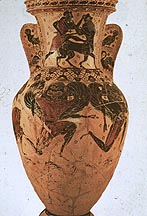

The seventh century is known by scholars as the Orientalizing period. This is a period of dramatic change in Greek art as Greek culture expands out and comes under the influence of non-Greek, especially Near Eastern cultures. With this encounter with non-Greek cultures, the Greeks developed a strong sense of cultural identity. While the Greeks were divided politically into fiercely independent city-states, there was still a strong sense of intense Greek identity through the shared language and culture. As Greeks came into contact with other cultures, they emphasized the difference between themselves and others. It is in Greek culture that the concept of the "barbarian" was invented. "Barbarian" ultimately is a Greek word. It was used by the Greek to identify a non-Greek speaker, one who speaks nonsense or "bar bar". Greek art during the seventh century witnesses a fascination with the monstrous. New monsters like the sphinx and griffin become popular. Medusa and her sisters the Gorgons exemplify this fascination. As evidenced by the examples illustrated above, the Orientalizing artist did not have a canonical form for the visual form of Medusa. The relief vase represents her as a centaur, a popular monstrous figure in early Greek art, while the Eleusis amphora represents the Gorgons with heads that look like cauldrons. It is only at the end of the seventh century as illustrated by the Nessos amphora that artists settle on a canonical form.

In your journal compare the figure of Medusa in seventh and sixth century Greek art back to the Minoan snake goddess.

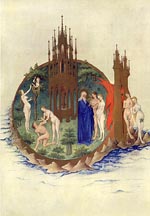

Consider in your journal the parallels between the Medusa story and the Old Testament story of the Temptation and Fall of Man from the book of Genesis. I illustrate this story with a miniature from the early fifteenth, French Book of Hours known as the Trés riches heures made for Jean, Duke of Berry.

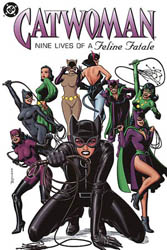

Consider in your journal, the relevance of this material to the creation of the character of Catwoman by Halle Berry in the 2004 film:

In preparing this webpage, I read the Wikipedia article on Catwoman. In that article the original creator of Catwoman, Bob Kane is quoted as saying: I felt that women were feline creatures and men were more like dogs. While dogs are faithful and friendly, cats are cool, detached, and unreliable. I felt much warmer with dogs around me—cats are as hard to understand as women are. Men feel more sure of themselves with a male friend than a woman. You always need to keep women at arm's length. We don't want anyone taking over our souls, and women have a habit of doing that. So there's a love-resentment thing with women. I guess women will feel that I'm being chauvinistic to speak this way, but I do feel that I've had better relationships with male friends than women. With women, once the romance is over, somehow they never remain my friends. Chauvinistic attitudes are hard to die! |

The story of Medusa has been picked up in contemporary feminist theory. Read the excerpts from the 1971 essay entitled "The Laugh of Medusa" by the French feminist writer Hélène Cixous. Respond to these excerpts in your journal.

In another context, I wrote this account of the "The Great Goddess." See its relationship to the comparison of the Minoan snake goddess and the Medusa figure.

The Great Goddess

The "Venus of Willendorf", c. 30,000-25, 000 B.C., Paleolithic (see the webpages constructed by Christopher Witcombe dedicated to the Venus of Willendorf)

Preceding the introduction of the patriarchal system of male sky gods, early Europe was dominated by the so-called Great Goddess, a powerful, creative force who through parthenogenesis (conception without sex) gave birth to the universe. She was the source of the great cycle of existence --life, death, re-birth. The Great Goddess appears in mythologies from all over the world:

| Greek | Gaea and Demeter |

| Roman | Ceres, Tellus, and Terra Mater |

| Egyptian | Isis |

| Sumerian | Inanna |

| Babylonian | Ishtar |

| Norse | Nerthus |

The Great Goddess unites opposites within herself: light/ darkness, upper and lower worlds, birth-death-and re-birth. She is both terrifying and beneficent.

See Chris Witcombe's essay on the Minoan Snake Goddess.

The so-called Snake Goddess from Knossos possibly presents the Great Goddess as she was conceived of within Minoan culture. We need to be careful not to read into the snakes held by this figure malevolent forces associated with serpents in the stories like the Garden of Eden and Medusa, that dominate in western culture. The serpent is a totem of the cycles of life, death and rebirth and the seasons. It is the connection to the fertile earth and to the underworld. It also symbolizes immortality as it was thought to shed its skin indefinitely.

The unity of the Great Goddess becomes divided in Greek mythology. Many scholars argue that this division occurs with the introduction of a new culture and religious imagination. Indo-Europeans like the so-called Dorians who apparently invaded the eastern Mediterranean during the end of the second millenium introduced the male sky gods and a much more militaristic culture. The cyclical conception of nature that existed apparently with the Great Goddess becomes divided into clear binaries. Imagine reality conceived as cycle where life and death, light and dark, etc. are seen as a part of a great cycle rather than being divided. The table below presents a partial list of a series of binaries that are regularly found in Greek art and culture:

Greek |

Non- Greek (Barbarian) |

Male |

Female |

Civilized |

un-Civilized (wild) |

Order (cosmos) |

chaos |

Rational |

Irrational |

Human |

Animal |

The Olympian gods were ultimately descended from Gaea. According to Hesiod's account of the creation of the universe presented in his Theogony, Gaea along with Tartarus and Eros, was born from Chaos, or at the same time. Without a mate she parthenogenetically bore Uranus (sky), Ourea (mountains), and Pontus (sea). With Uranus, Gaea gave birth to the Titans and Cyclopes. Gaea encouraged Cronus, the eldest Titan, to take a sickle and castrate his father Uranus. Cronus through Rhea became the father of the eldest Olympian gods (Zeus, Hera, Demeter, Hestia, Poseidon, and Hades). In turn, Zeus, the youngest son of Rhea, overturned his father Cronus. Although Gaea had encouraged the elevation of Zeus to king of the Olympians, she ultimately turned against him. She set her offspring the monster Typhöeus and the Giants against Zeus who ultimately prevailed. In Greek mythology, the direct off-spring of Gaea become identified as chthonic forces (from the earth) that become subdued by the Olympians and their followers.

This succession myth and the ascendance of Zeus and the Olympian Gods over the chthonic powers of Gaea and her off-spring echoes the introduction of the patriarchal Indo-European sky-gods into the Mediterranean world and the subordination of the Great Goddess. Scholars examining the remains of Minoan culture have wondered whether it was a matriarchal society. There is no certainty to this conclusion, but for the historical period of Greek culture extending from at least the eighth century B.C. matriarchy represented the opposite of everything that was Greek, civilized, and "normal." Matriarchy was posited as the horrific and chaotic alternative to patriarchy and thereby served as a tool to explain and validate patriarchal institutions, customs, and values.

With the supremacy of Zeus and the other Olympian gods established, Gaea's position is eclipsed. Demeter, the sister of Zeus, incorporates many of the aspects of the Great Goddess, while the different functions of Gaea are divided among goddesses. Under the Olympian Gods, earth and heaven are split eternally. In myth heroes and gods are created to dominate and subjugate the female and natural forces over and over again in various forms, the most common of them being gigantic snakes and serpent monsters. The chthonic identity of the Great Goddess becomes associated with powers of darkness, chaos, and death that need to be subdued by the Olympian gods. What had been cyclical with the Great Goddess becomes cut so that instead of being associated with the cycle of life, death, and regeneration, she becomes identified with the negative functions.

See Chris Witcombe's essay on the Minoan Snake Goddess. |

A comparison of one of the large number of representations of the story of Perseus Medusa from Archaic Greek art to the Minoan Snake Goddess illustrates the profound change that occurred with the supremacy of the Olympian Gods. A striking aspect of the Snake Goddess is her frontality combined with her hypnotic stare. The power of this stare was probably intended to strike the original viewers with intense religious feelings of of terror and awe. This expression transcends categories of good and evil. On the other hand, it was the sight of the "terrible" visage of Medusa that would turn men into stone. The powerful gaze in the Minoan work becomes entirely negative and demonized and something to be overcome in the figure of Medusa. Perseus, the son of Zeus and the mortal Danae, slays Medusa with his sword, and thus he destroys the terrifying chthonic powers of the female (for more on Medusa see the paper by Alicia Le Van).

The following excerpt from Bullfinch's Mythology illustrates how the demonization of Medusa persists into our modern imagination:

| Medusa was a terrible monster who had laid waste to the country. She was once a beautiful maiden whose hair was her chief glory, but as she dared to vie in beauty with Athena, the goddess deprived her of her charms and changed her beautiful ringlets into hissing serpents. She became a cruel monster of so frightening an aspect that no living thing could behold her without being turned into stone. All around the cavern where she dwelt might be seen the stony figures of men and animals which had chanced to catch a glimpse of her and had been petrified with the sight. Perseus, favored by Athena and Hermes, the former of whom lent him her shield and the latter his winged shoes, approached Medusa while she slept, and taking care not to look directly at her, but guided by her image reflected in the bright shield which he bore, he cut off her head and gave it to Athena, who fixed it in the middle of her Aegis. |

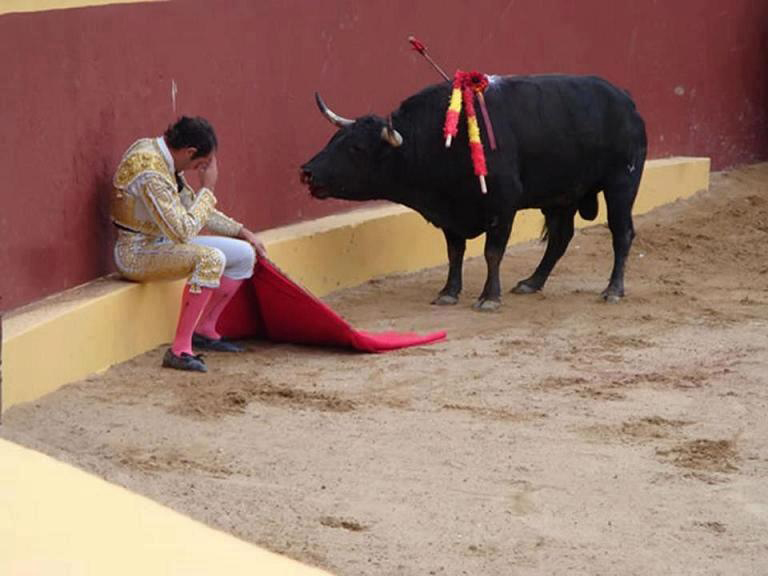

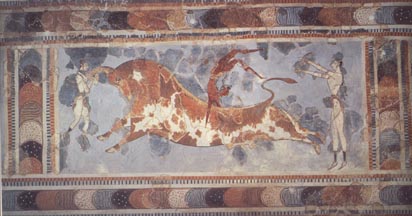

Another major work associated with Minoan art is a fresco from the palace of Knossos on Crete. It was painted about 1450 BCE, and scholars have speculated about the nature of the practice shown here. It anticipates the important role the bull will play in western culture down to Bullfighting in Spain.  What is interesting is the different relationship of the humans to the bull in the Minoan image from what is found in later art. Consider here the relief sculpture from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia coming from the middle of the fifth century BCE.

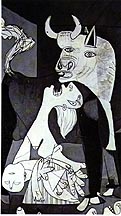

What is interesting is the different relationship of the humans to the bull in the Minoan image from what is found in later art. Consider here the relief sculpture from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia coming from the middle of the fifth century BCE.  The relief is part of a series of panels that represent the Labors of Heracles. This particular one illustrates Heracles defeating the Cretan Bull. In this context it is important to remember the myth of King Minos and the Minotaur. As an example of the continuity of the imagery of the Minotaur in western art consider the illustrations included in the article by Martin Ries entitled Picasso and the Myth of the Minotaur. At the end of the semester we will be considering Picasso's Guernica which includes an image of the bull.

The relief is part of a series of panels that represent the Labors of Heracles. This particular one illustrates Heracles defeating the Cretan Bull. In this context it is important to remember the myth of King Minos and the Minotaur. As an example of the continuity of the imagery of the Minotaur in western art consider the illustrations included in the article by Martin Ries entitled Picasso and the Myth of the Minotaur. At the end of the semester we will be considering Picasso's Guernica which includes an image of the bull.