Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments

Art & Politics

| [I]t is the pretence of the museum that they [sic] are an apolitical organization. And yet...the board of trustees are exactly the same people who devised the American foreign policy over the last twenty-five years...[they] favour the war, they devised the war in the first place and wish to see the war continued, indefinitely. The war in Vietnam is not a war of resources, it is a demonstration to the people of the world that they had better not wish to change things radically because if they do the United States will send an occupying, punishing force--Carl Andre in an interview with Jeanne Siegel in Studio International in 1970. |

I did my

undergraduate and first Masters degree at Case Western Reserve University

in Cleveland in the late 1960's and early 1970's. As an art history student,

I was fortunate to spend much of my time working in the Cleveland Museum of

Art. This was an eventful period socially and politically. Like many American

cities of the period, there were profound racial and economic tensions in

the city of Cleveland. Located in an area known as University Circle, the

Cleveland Museum of Art was on a fault-line

dividing the troubled "inner-city" from the well-to-do suburbs like

Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights. Like any campus of the period, CWRU

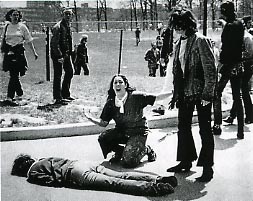

was a center of Vietnam Protests.  I remember vividly the night

I remember vividly the night  in

early May of 1970 when a group of students from Kent State came to a protest

meeting

to give first-hand testimony to the shootings on that campus earlier that

afternoon. I remember the strange night of the first national draft lottery

when the accident of the day of one's birth determined whether you might

be

drafted to serve in what you considered to be an unjust war. I remember the

muffled sound of an explosion one night in March of 1970. When I arrived

at

the museum the next day, the police had roped off the area in front of the

museum. In the center was the shattered remains of Rodin's

Thinker.

in

early May of 1970 when a group of students from Kent State came to a protest

meeting

to give first-hand testimony to the shootings on that campus earlier that

afternoon. I remember the strange night of the first national draft lottery

when the accident of the day of one's birth determined whether you might

be

drafted to serve in what you considered to be an unjust war. I remember the

muffled sound of an explosion one night in March of 1970. When I arrived

at

the museum the next day, the police had roped off the area in front of the

museum. In the center was the shattered remains of Rodin's

Thinker.

During those

tumultuous years as I climbed the stone steps of the Cleveland Museum and

entered through the facade modelled on the Erechtheum

from the Athenian Acropolis, I thought of the museum as a refuge from the

social and political unrest. I saw myself in an educational tradition that

includes  the English schoolboys represented on the steps of London's National

Gallery of Art in Tissot's painting London Visitors. The museum as

a cultural preserve was an image the Cleveland Museum sought to project. The

director of the museum was Sherman Lee, probably the most respected arts administrator

of the era. Central to Dr. Lee's philosophy was the fundamental belief that

art should not become involved in politics. At this same period, the Metropolitan

Museum of Art was being run by Thomas Hoving, who had gained a reputation

of trying to shake up the stodgy institution. Exhibitions like Harlem on My Mind were extremely controversial. The New York Times would

regularly run pieces lauding the efforts of Dr. Lee at Cleveland while attacking

Hoving at the Met. In a New York Times article entitled "Concerning Questions of Quality" (NYT, June 12, 1966), the art critic Hilton Kramer lauded the Cleveland Museum's dedication to quality and its detachment from current political and social issues:

the English schoolboys represented on the steps of London's National

Gallery of Art in Tissot's painting London Visitors. The museum as

a cultural preserve was an image the Cleveland Museum sought to project. The

director of the museum was Sherman Lee, probably the most respected arts administrator

of the era. Central to Dr. Lee's philosophy was the fundamental belief that

art should not become involved in politics. At this same period, the Metropolitan

Museum of Art was being run by Thomas Hoving, who had gained a reputation

of trying to shake up the stodgy institution. Exhibitions like Harlem on My Mind were extremely controversial. The New York Times would

regularly run pieces lauding the efforts of Dr. Lee at Cleveland while attacking

Hoving at the Met. In a New York Times article entitled "Concerning Questions of Quality" (NYT, June 12, 1966), the art critic Hilton Kramer lauded the Cleveland Museum's dedication to quality and its detachment from current political and social issues:

| The Cleveland Museum of Art is an extraordinary institution, a repository of masterpieces great and small spanning the centuries from antiquity to modern times, and it is one of the most felicitous museums to be found anywhere in the world. But as an institution, it has never made a secret of its detachment from the hurly-burly of the contemporary art scene. Insofar as this detachment permits the Museum to pursue without compromise its principal tasks, which devolve upon its great permanent collections and the kind of scholarship and connoisseurship that are the life's blood of collections like Cleveland's, it seems to me a wholly admirable policy-- and policy of a kind that fewer and fewer museums are willing or able to sustain. |

The belief in the fundamental separation between art and politics was as much a conviction in the art world as the idea of the separation of church and state. Dr. Lee came to my dormitory one evening to engage in a discussion about the relationship of art and politics. He asked the gathered students to name great works of art that were produced at the service of politics. We all immediately cited Picasso's Guernica and the history paintings of David, but then we began to stumble. Art should deal with timeless truths and not stoop to become "relevant" to the current social or political cause. In an article entitled "Artists and the Problem of Relevance" published in The New York Times (May 4, 1969), Hilton Kramer wrote:

| Museums, too, have tended --correctly, I think-- to be wary of political involvement. Though many museums now conduct a variety of community programs --designed for the most part, to bring art more directly into the lives of those who have heretofore had little acquaintance with it-- they regard these programs as ancillary to their principal function, which is to act as a distinterested custodian of the artistic achievements of both the near and the distant past. |

The Cleveland Museum prided itself on its active education program that introduced school groups to the artistic accomplishments of past cultures. The educational program was defined in terms of its social responsibility of enlightening and inculcating humanistic values. It would not be understood as indoctrinating its audience to the ideologies of the ruling elites.

This same philosophy, or what we today might call ideology (in the 1970s, the Soviets had ideology, we didn't), was expressed by Sir Kenneth Clark, a renowned British art historian, who produced in the early 1970s a highly influential BBC television series entitled "Civilisation" which chronicled the course of Western art from Antiquity to the Modern era. For Lord Clark the experience of art is a spiritual transformation. He wrote of the rationale of the museum:

| The only reason for bringing together works of art in a public place is that ... they produce in us a kind of exalted happiness. For a moment there is a clearing in the jungle: we pass on refreshed, with our capacity for life increased and with some memory of the sky. |

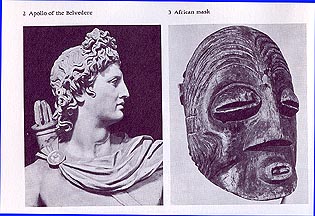

It is chilling today to read excerpts from the book based on the "Civilisation" series in the light of the turmoil of Cleveland of the period. In his opening chapter, Lord Clark makes a comparison between the head of the Apollo Belvedere and an African Mask:

He writes:

| I don't think there is any doubt that the Apollo embodies a higher state of civilisation than the mask. They both represent spirits, messengers from another world --that is to say, from a world of our own imagining. To the Negro imagination it is a world of fear and darkness, ready to inflict horrible punishment for the smallest infringement of a taboo. To the Hellenistic imagination it is a world of light and confidence, in which the gods are like ourselves, only more beautiful, and descend to earth in order to teach men reason and the laws of harmony. |

Imagine a loyal member of the Cleveland Museum reading this passage in the comfort of their Shaker Heights house in the early 1970s. Can there be any doubt that there was profound distrust and misunderstanding between the social classes of Cleveland? Clark's art historical judgment of an African mask confirmed the Junior Leaguer's racial stereotypes. There was little ambiguity in the race and gender of the gods "like ourselves" for Clark and his imagined readers. I remember again the muffled explosion on that March night in 1970.

What I consider to be particularly dangerous about Clark's statement is how it is based on a rhetorical strategy of constructing a dichotomy between "us" and an "other." We will examine this later in the semester, but the strategy is used to justify us by drawing the contrast to the other. Clark is depending on our historical understanding of "our" cultural roots in the Classical Civilization of Greek and Roman culture. Note how the rhetorical strategy employed by Clark can be re-applied in different contexts. For example, substitute "Arab" or "Iraqi" for "Negro" to see how adaptable the strategy is. Also pay attention to the imagery built into the rhetorical strategy. We can see included in the statement a system of oppositions: higher/ lower, civilisation / non-civilisation (primitive), light / dark, justice / taboo, reason / irrationality, harmony / dis-harmony.

Recent criticism has demonstrated that the museum is not a neutral institution, but is complicit in maintaining the existing social, political, and economic hierarachies. Fred Wilson, a contemporary artist, has devoted his work to questioning the prevailing structures implicit in the museum. In 1992, at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore he created an exhibition entitled "Mining the Museum" in which he included an installation entitled Furniture with Whipping Post that starkly calls attention to the social injustices of the past at the same time making problematic the practices of the museum:

Samuel Jennings, Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences, 1792.

This painting by Samuel Jennings comes from about the same time as the chair and whipping post in Fred Wilson's installation.

In that dialogue with Dr. Lee, no one would have thought of seeing works like Michelangelo's Creation of Adam from the Sistine Ceiling in political terms. The situation has changed dramatically today. In the last generation the discipline of Art History has been transformed by a variety of critical theories. The elitist notion of the work of art as belonging to the preserve of high culture has been seriously questioned. Works of art like other artifacts of culture have become seen as playing critical roles in constructing our political and cutural identities. Feminist art historians, for example, look at works like Michelangelo's Creation of Adam and see them as forming gender identity and lending authority to the patriarchal nature of Western Society. The heroic male figure receiving power from above can be seen as a central theme in Western Culture from Antiquity to the present world. Consider the images included on the web page entitled Man is the Measure of Things. Also understand that an image like the Creation of Adam was painted between 1508-1511 at the very beginning of the European age of discovery. Understand how the authority granted by God to Adam in this image can be seen as justifying European conquest under the banner of religious conversion of the non-European world. Note the important parallels between Michelangelo's image and the following late 16th century image showing "Amerigo Vespucci Discovering America."

Today a common theme of any survey course is the role art plays in articulating religious, political, social, and cultural identity. Many of the great works of art have been commissioned by patrons directly concerned with justifying power. Consider the difference in attitude between the Clark passages cited above and the following quotation from the writings of Griselda Pollock:

Culture can be defined as those social practices whose prime aim is signification , i.e. the production of sense or making orders of 'sense' for the world we live in. Culture is the social in which are produced those images of the world and definitions of reality which can be ideologically mobilized to legitimize the existing order of relations of domination and subordination between classes, races, and sexes.---Vision and Difference, p. 20.

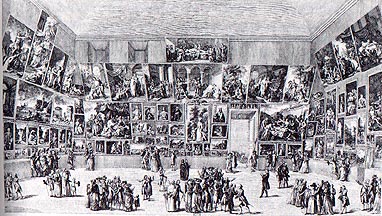

As a way of introducing our course, I would like to consider a major late eighteenth century painting. In 1784, the French painter Jacques Louis David painted the Oath of the Horatii and intended it to be exhibited in the Salon, a great public exhibition of art in Paris (read excerpts on the Salon from Thomas Crow's Painting and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris). The drawing below shows David's painting prominently displayed in the Salon of 1785:

David's Oath of the Horatii has become the prime example of the late eighteenth-century style we call Neo-Classicism. David was what the French characterize as the "artiste engagé." He was committed to the public role of the artist, and the use of painting as a pedagogical device to instruct the public. In creating this work David was committed to having his work express what he considered to be "universal values." The success of David's painting is still manifested today by our ability to read the painting without knowledge of the complex story drawn from Roman history it is based on.

In preparation for our discussion of the painting, I would like you to respond to the following questions in your journals: How would you describe the organization of the painting? Can you find any logic in the organization of the different elements of the painting? What words come to mind when you consider the painting? What social and political messages do you read into the painting? How are these articulated in the painting? What do you think about David's notion of using art to express "universal values"? Why would a French artist of the end of the eighteenth century have based a painting on an episode from early Roman history?

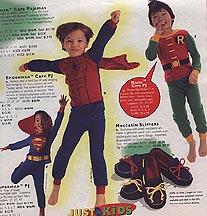

Compare the gender contrasts used by David with the following ad for boys' and girls' pajamas: