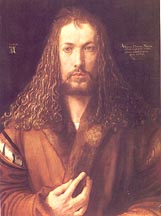

Koerner, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art: p. 19: In the Louvre painting the artist appears like any young, middle class Nuremberg burgher, outfitted with attributes of a fiancé and placed within the common German pictorial type of the betrothal portrait.

In the Prado panel, perhaps for the first time

in the history of art, self-portraiture distinguishes itself from

other kinds of portraits. Dressed in lavish and festive clothing

of modish taste and design, and wearing the expensive doeskin

gloves that were a Nuremberg specialty, Dürer elevates himself

above the modest social rank into which he was born, above even

the apparent status of his patrician sitters the Tuchers and the

Krels, whom he portrayed in far less ostentatious and cosmopolitan

garb and setting. Italian aspects of the painting's execution

--its soft modeling, stable architectonic construction, and atmospheric

landscape passage-- bear witness to foreign sources of the artist's

conception of himself. For it is in Italy, during his first trip

there in 1494-95, that he encountered a new, humanistic conception

of the sovereignty of the artist, a conception that he recognized

was missing in his own native Germany; hence his famous remark

to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer in a 1506 letter written from

Venice: "Here I am a gentleman, at home only a parasite [schmarotzer]."

The Prado panel combines artistic pride, evident in the daring

of its pictorial invention and voiced in its inscription, with

Dürer's personal pride in who he is, how he looks, where

he has been, and what he is worth. It celebrates the power of

the individual and elevates what self-portraiture is intended

to depict: not merely the look and status of its maker, but the

underlying idea of painting itself.

p. 39 Whether these claims concerning Dürer's newness are

historically accurate, whether the Prado panel expresses --and

for the first time-- the painter as representative self, is not

at issue here. In the litany of beginnings that surround Dürer's

self-portraits, what strikes us most is the art historian's faith

in the originary power of art --a faith that assumes an almost

religious character when what is at stake is the historical source

of the self.

Therefore there is something encouraging about Dürer's 1500 Self Portrait. In the sheer monumentality of the picture's design, in the fearful symmetry and directness of address that solemnize our encounter with the artist's likeness, Dürer seems to affirm and sanctify the epochal change that his self-portraits are believed, in retrospect, to instantiate. Here a painting that appears wholly to validate the belief that Dürer's self-portraits represent a passage from one age to another. The panel's date of 1500 takes on special importance, and not only because its round number cannot but be regarded as epochal. In its prominent placement near the center of the darkened field at the upper left, one also senses that the artist has fashioned the moment of his painting as a point of passage, indeed, that his self-portrait is the appropriate emblem of that great year. As we shall see, the Munich panel may have been produced as part of a larger celebration of the saeculum staged by German humanists in the circle of Conrad Celtis. Celtis fashioned the year 1500 into a symbol of his own culture's momentous advance over the past, thereby inscribing the process of history into a secular myth of progress. The 1500 self-portrait is Dürer's pictorial response to this project of self-presentation mixed with historical consciousness.

p. 53 Dürer's 1500 Self-Portrait

as emblem of the originary and productive power of the artist.

Here is condensed, in one panel, the whole by now familiar, domesticated,

discredited, and estranged discourse of the 'dignity of man.'

Dürer's airtight placement at the center of the visual field,

which allows not so much as a single hair to stray out of representation,

affirms the consubstantiality of product and producer. His erect

enface posture dramatizes the personal force of the artist as

representative man. Dürer stands dressed in the fur-trimmed

coat worn by patricians and humanists; he demonstrates his learning

at once in the geometry of the iamge and in the difficult Latin

of his inscriptions; all in order to assert, once and for all,

the Renaissance painter's ascent from craftsman to artist, from

manual to intellectual laborer. This elevation is interepreted

in the panel's controlling figure. Dürer as we shall see

fashions his likeness after icons of Christ. In analogizing artists's

portrait and cult image of God, in celebrating his art as the

vera icon of personal skill and genius, Dürer realigns

the terms of artistic and human self-understanding. He leaves

behind centuries of image production in which authorship either

was not registered or else was framed in postures of submission,

as in the self-portrait of the 13th c. chronicler and illuminator

Matthew Paris crouched beneath the Virgin in the bas-de-page.

What Dürer reifies here no longer seems as 'natural' today as it did a few decades ago. Categories like self, man, art, modernity, genius, and labor now appear to many of us as fictions who historicity and ideological motivation have been subject of much recent scholarship on the Renaissance.

p. 55: This book does not offer a historical explanation of the moment of self-portraiture. It does not, that is, propose a diachronic causal answer to the question, What brought about Dürer's likenesses of himself? One can imagine a wide range of answers, each plausible but insufficient in itself. One could cite certain artistic and cultural influences as precipitating conditions: The Renaissance ideology of the dignity of man, first established in Italy during the fifteenth century, arrived in Germany through Dürer and occasioned his self-celebrations; new styles of piety, caused by broad changes in society, redefined the function of images, and Dürer's self-portraits are one response to this new function; an intensified interest in self-control and self-exploration, evident in all spheres of culture, affected the art of Dürer and his heirs. Or one could propose broader social and economic causes: the breakdown of Feudal modes of production and the rise of merchant capitalism in German imperial cities at the eve of the Reformation, along with attendant changes in the legal and economic construction of the individual, precipitated innovations in artistic self-definition. The technology of printing, together with the development of an art market, required individual artists to signal what was theirs in more compelling and totalizing ways. A successful, literate, urban middle class initiated new patterns of patronage to which self-portraiture catered in complex but definable ways. A new, meritocratic administrative class, supported by Emperor Maximilian I, found emblems of the value of personal talent in Dürer's portrait likenesses. Changing power relations between individuals and larger social structures (formations of family, gender, class, and state) necessitated new models of identity that Dürer's pictures could provide.

p. 64 By visiting Italy, Dürer shared an experience with only the most cosmopolitan Germans: the sons of the great urban merchant families, young men who journeyed south to study at the Italian universities or to acquire business experience abroad. The mountainous landscape of the Prado panel at once signals the artist's kinship with this elite and places the portrait likeness vigorously in the world. Closed off on one side by window's edge and on the other by the panel's limit, the landscape situates the viewer's gaze at a single, contingent point in space...

pp. 66-67: Our account thus far has assumed one thing: the Munich panel's intended function was to preserve for posterity one self that is uniquely Dürer's. A glance at the artist's earlier likenesses, however, complicates our ideas about the unity and function of the self /p. 67 in self-portraiture at 1500. Viewed in succession, these works chronicle not so much one person's physical and artistic maturation as a sequence of roles enacted by the artist for a variety of occasions. In the Louvre panel of 1493 Dürer outfits himself dutifully as lover and as husband; in the Prado portrait he appears as worldly gentilhuomo ; and in the Munich picture he is something more lofty and audacious, a being fashioned in the image of God. If we sense the person 'Dürer' behind this change of costumes, it is only in the gap between, one the one hand, the garb that fixes the sitter into his various roles and, on the other hand, the sitter's face that, remaining constant through the panels, gazes out of the picture with a conviction and an immediacy at odds with the variously clothed body. Thus in the Louvre Self-Portrait, a spruce and eager Dürer, wielding his medicine against impotence, presents himself to his fiancée. And yet the attention and flattery he lavishes on his own appearance, the strong sense we have of Dürer relishing the specular act of self-portraiture would be the artist's narcissism at odds with his role. In the Prado Panel, Dürer's familiar face peers out at the modern viewer as if somehow mocked by his own costume. This does not tell us what Dürer was "really" like, only perhaps what we how he was not like. And in the 1500 Self-Portrait, as we shall see, Dürer thematizes the unbridgeable rift between himself, in all his vanity, narcissism, and reveals himself to be mere man. My point herre is not to decipher an inner subjectivity that is constant in all Dürer's self-portrait, but rather to demonstrate how, to a modern sensibility, these works are strangely anonymous. What we think should be their subject, Dürer, emerges only negatively, at a distance from a role and therefore from the initial function of the panel.

This effect should not surprise any modern student of the sixteenth century. As Stephen Greenblatt has argued in his now classic study of pyschic mobility in the Renaissance, during this period "there appear to be an increased self-consciousness about the fashioning of human identity as a manipulable, artful process." Dürer can style himself as lover or as an Italian gentleman, just as later he will fashion himself as Christ and as Adam, celebrating all the while his own capacity to mold himself in whatever manner he chooses....

p. 79: In fashioning his own most monumental

likeness after the cultic image of the Holy Face, Dürer makes

particular claims for the art of painting. By transferring the

attributes of imagistic authority and quasi-magical power once

associated with the true and sacred image of God to the novel

subject of self-portraiture, Dürer legitimates his radically

new notion of art, one based on the irreducible relation between

the self and the work of art.

Focusing attention on the Munich panel as image, we shall observe how the 'self' of Dürer's self-portraits functions within a larger argument concerning the status of the visual image at 1500. It is within this argument, internal, and specific to painting, and not within the debate over Dürer's personal piety, that the play between tradition and innovation, history and modernity, religion and art is properly staged.

pp. 84-85: What knits together the various

theological interpretations of the acheiropoetos , and

what motivates its invocation by Dürer in his Self Portrait,

is its myth of representation. The idea that Christ produced his

authentic self-portrait without the agency of human hands expresses

the dream of an autonomous, self-created image, a picture produced

instantly in its perfect totality, outside the bodily conditions

of human making that are embedded in the fallen dimension of time.

Through its mode of production, what is fashioned without hands

enters into a special, elevated status among things in the world.

St. Paul speaks of Christ's priesthood as "a greater and

more perfect one, not made by men's hands, that is not belonging

to this created world." (Heb. 9:11). In the Platonic and

Philonic tradition of early Christianity, the divine prototypes

of all earthly things were called .acheiropoetoi.....

p. 85: At first sight, the kind of painting represented by Dürer's Self-Portrait is precisely one in which the visible signs of human making --for example, brushwork and the material presence of paint-- are all but imperceptible. Nor does the artist-as-sitter appear to be engaged physically in the act of fashioning his likeness. Dürer gazes out at us from a completed world in which every hair, every visible surface, is wholly accounted for --as if the moment of self-portraiture had indeed been the total and instant doubling of the living subject onto the blank surface of the panel. The inscription painted at the upper right support this idea. Dürer proclaims that he has fashioned his likeness with propriis coloribus, a complex phrase meaning not only 'eternal' or 'permanent' colors, but also colors that are Dürer's very own --colors that are somehow magically consubstantial with the thing they represent. Through the visual allusion to the vera icon, Dürer can raise to a higher register this conceit of a perfect equivalence between image and model by comparing his work to the miraculous self-portraits of Christ.

Chapter 10: Law of Authorship: p. 203: The artist's use of a personal symbol or monogrammed initials to identify a work he has made emerges in the North out of various spheres of economic and juridical life at the end of the Middle Ages. In Germany since at least the thirteenth century, commercial, diplomatic, and legal transactions were increasingly dependent on written documents, and yet, for an educated few, the vast majority of craftsmen, small merchants, and farmers were illiterate. The coat of arms, trademark, and Haus- and Hofmarken when used to identify property owned by a person, family, or institution; the personal device or seal employed to 'sign' or notarize contracts and other legal documents; the marks of stonemasons, which indicated the identity of the producer so that he could be paid for pieces he fashioned; and the goldsmith's plate mark, which identified the maker and guaranteed the quality of the gold used -- all were ways of registering the person in law and commerce within the culture out of which Dürer emerged.

Between 1420 and 1440, graphic artists appropriated this practice

from other crafts, placing within their engravings some personal

sign. This was partly a response to the new economic demand of

their trade. Prints were not financed by commission or sold only

locally- their production by a heavy press required an outlay

of capital far beyond the costs of plate, paper, and ink and their

distribution often depended on the new, erratic, and intensely

competitive industry of the printed book. The printed image, therefore

needed to advertise its origins and assert its value differently

than painting did, through a recognizable sign of authorship....

p. 204 What is important is that the sign be recognizable and

consistent throughout an oeuvre, linking the individual print

to its producer, be it an artist, a shop, or a publisher. For

in the medium of engraving, the artist is potentially absent both

from the community of viewers who initially purchase and use the

image, and from the actual process of production, which demands

manual labor from the artist only in fashioning the original plate.

The monogram emerges within this absence, as part of a strategy

for making mechanical reproduction pay.

When Durer takes over this native German practice, he expands

its scope and fundamentally changes its message. As early as 1493

Dürer places his initials on panel paintings and drawings,

something that is unknown to Dürer's teacher Michael Wolgemut;

by 1494-95 he begins to monogram not only his engravings (the

first thus monogrammed is the Virgin with the Dragonfly),

but also his single-leaf woodcuts, a practice that presupposes

fundamental changes in the condition of trade for his medium.

Dürer could have derived his strategy both from his father,

who as a successful and cosmopolitan goldsmith would have understood

the form and function of plate marks, and from the artists with

whom he trained in Nuremberg. Wolgemut had already begun to free

the art of woodcut designing from the domination of publishers,

changing what had been the specialty of professionally employed

"illustrators" into a lucrative industry for painters.

In illustrated books like the Shatzbehalter of 1491 and

Hartmann Schedel's Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, Wolgemut

organized the financing and publication of his shop's productions,

employing the services of the local printer, Anton Koberger. Dürer,

who was Koberger's godson, took this process one step further.

In his famous Apocalypse woodcuts, published in Latin and

German editions in 1498, he was at once designer and publisher,

having purchased his own printing press about 1497. The artist followed

this practice in all his printed works, even naming himself as publisher of his own theoretical tracts (Underweysung der Messung of 1525 and the Befestigungslehre of 1527 are gedruckt von Albrecht Dürer). After his death his widow Agnes continued this practice, printing the 1528 Proportionslehre under her own name and defending her copyright in the courts of Nuremberg. The artist's monogram, appearing in all his major woodcuts from 1496 on, thus functioned to indicate the image's design and publisher.

In producing his woodcuts, Dürer monopolized all stages of

an image's making, from invention and execution to publication

and sale. He thus freed himself from any dependency on the large

book publishers, with their complex division of labor (Coberger, for example, employed more than 150 journeymen and had branch offices in Paris, Lyons, Budapest, Leipzig, Regensburg, Wroclaw, and Frankfurt). This autonomy affected his whole conception

of himself and his art. More than anyone else, Dürer transformed

the conditions of the trade for artists working in Germany. What

had been a craft financed by commissioned works, and organized

in large hierarchically organized shops, became through him a

more diversified industry, producing a range of commodities --

for portraits and panel painting to engravings, woodcuts, book

illustrations, and drawings --to be sold on the open market and

featuring, as its essential product, a work particular to the

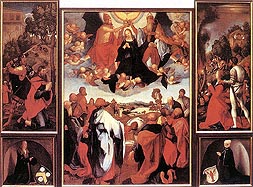

singular master. It is significant that although, from about 1500 on, Dürer was by far the most famous and sought-after painter in Germany, he never produced a work in that dominant pictorial genre of pre-Reformation Germany, the large winded retable altarpiece. [an extraordinary example is the Isenheim Altarpiece with paintings by Matthias Grunewald.]The retable consisted of a number of elaborate components. At the center, the shrine or corpus was a shallow box containing depictions of the narrative, personage, or mystery to which the altar was dedicated; crowning the shrine, the Auszug or Gesprenge consisted of carved vaultings, foliage, and finials; below, a Sarg or predella raised the shrine above the altar table; and wings, either painted or sculpted in low relief, served to protect and conceal the more precious shrine on workdays. These structures, sometimes huge, were often financed publicly and used in the collective rituals of the Christian cult. They required a complex division of labor between a number if different craftsmen (painters, sculptors, joiners, and locksmiths, along with their various apprentices /p. 206: and assistants). The painter was generally relegated to a subordinate role of polychroming the statues and relief sculpture or decorating the external panels, frames, and rear of the altarpiece. Dürer would have been familiar with this mode of production from his training under Michael Wolgemut, who continued to operate the largest workshop in Nuremberg (and one of the largest in Germany) until his death in 1519....

It is significant that although, from about 1500 on, Dürer was by far the most famous and sought-after painter in Germany, he never produced a work in that dominant pictorial genre of pre-Reformation Germany, the large winded retable altarpiece. [an extraordinary example is the Isenheim Altarpiece with paintings by Matthias Grunewald.]The retable consisted of a number of elaborate components. At the center, the shrine or corpus was a shallow box containing depictions of the narrative, personage, or mystery to which the altar was dedicated; crowning the shrine, the Auszug or Gesprenge consisted of carved vaultings, foliage, and finials; below, a Sarg or predella raised the shrine above the altar table; and wings, either painted or sculpted in low relief, served to protect and conceal the more precious shrine on workdays. These structures, sometimes huge, were often financed publicly and used in the collective rituals of the Christian cult. They required a complex division of labor between a number if different craftsmen (painters, sculptors, joiners, and locksmiths, along with their various apprentices /p. 206: and assistants). The painter was generally relegated to a subordinate role of polychroming the statues and relief sculpture or decorating the external panels, frames, and rear of the altarpiece. Dürer would have been familiar with this mode of production from his training under Michael Wolgemut, who continued to operate the largest workshop in Nuremberg (and one of the largest in Germany) until his death in 1519....

Although successful painters of the early sixteenth century were still enjoying lucrative commissions for retable altarpieces, the mature Dürer never participated in such a project. Perhaps he rejected the subordination of painting to sculpture inherent in the genre. Perhaps he recognized the financial disadvantage of being employed by another master or of belonging to such large-scale operations. The few altarpieces he did produce are all relatively small works, privately commissioned and financed, and they generally consist of a single painted panel in the mode of the Italian pala or ancora.  His most ambitious work of this kind, the 1511 Landauer Altarpiece, represents the first real break in Germany from the tradition of the retable, taking the form of a wingless image framed in an Italianate aedicula. Sculpture appears in an ancillary role, in the massive, classicizing frame designed by Dürer and executed by a local sculptor (perhaps Ludwig Krug). Again Dürer has monopolized the various stages and components of his commission, making the altarpiece, as much as possible, a one-man product.

His most ambitious work of this kind, the 1511 Landauer Altarpiece, represents the first real break in Germany from the tradition of the retable, taking the form of a wingless image framed in an Italianate aedicula. Sculpture appears in an ancillary role, in the massive, classicizing frame designed by Dürer and executed by a local sculptor (perhaps Ludwig Krug). Again Dürer has monopolized the various stages and components of his commission, making the altarpiece, as much as possible, a one-man product.

Dürer's rejection of the retable as the economic mainstay of his trade transcends the question of painting's status relative to sculpture, however.  It reflects Dürer's general ambivalence toward commissioned works as a source of income. His letters to Jacob Heller document the financial burdens and physical difficulties Dürer experienced in completing, the Ascension of the Virgin....

It reflects Dürer's general ambivalence toward commissioned works as a source of income. His letters to Jacob Heller document the financial burdens and physical difficulties Dürer experienced in completing, the Ascension of the Virgin....

Koerner, p 206: His Apocalypse woodcuts of 1498 would already have demonstrated to Dürer how his labor, invested in the medium of the print, could spread rapidly through Europe and beyond, earning lucrative returns along the way. As the artist writes to Heller on August 29, 1509: "In one year, I can make a pile of common pictures, so that no one would believe it possible that one man could do them all. One can earn something on these. But assiduous, hair-splitting labor gives little in return. That's why I am going to devote myself to engraving. And had I done so earlier, I would be today one thousand florins richer."

p. 207: Dürer was no less innovative

in his marketing practices than in his acquisition and use of

a printing press. Already by 1497 the artist experimented with

colportage as a means of selling his prints in towns and cities

throught Europe. A contract between Dürer and a certain book

hawker named Georg Koler testifies to this scheme. Paid a weekly

wage of half a floring, Koler agreed to peddle Dürer's engravings

and woodcuts "in the cities and towns he deems good and profitable;

and he should hawk and sell them for the highest possible price,

and carry them from one city and region to another, and offer

them for sale, letting nothing, neither play nor other frivolous

activities, hinder their sale, and the money he earns he will

send to the said Dürer forthwith."....

Ultimately, however Dürer's use of colporteurs brought him

near financial disaster. In a passage from his Gedenkbuch written

about 1506, Dürer complains that although he worked hard

with his hand he never profited much, for he sustained great losses

in bad loads and speculations. He adds : "The same is true

of servants who did not turn a profit. One died in Rome with great

loss of my wares. For this reason, when I was in the thirteenth

year of my marriage, I paid great debts with the money I/ p. 208

earned in Venice. " After 1506 Dürer never employed

professional agents again, preferring to sell his prints by less

risky methods, peddling them himself on his travels, arranging

their transport to foreign markets through merchants like the

Tuchers and Imhoffs or entrusting them to his wife, mother, and

maid, who sold them from stands at the fairs of Augsburg, Frankfurt,

and Ingolstadt as well as at the annual Imperial Relic Fair in

Nuremberg.... His inventive, if flawed, schemes of production,

advertising, and distribution reflect how, within the middle-class

urban milieu of Nuremberg at 1500, individuals could regard themselves

as makers of their own destiny, thwarted only by the deception

of other people or by the hazards of fortune....

The legal status of the professional painter in Dürer's Nuremberg

was particularly well-suited for creative commercial arrangements.

Contrary to what is frequently asserted in the Dürer literature,

painters of fifteenth and sixteenth century Nuremberg were not

bound together in a guild, as they were in virtually every other

German city, since as a result of the 1348 artisans' revolt, craftsmen's

guilds were generally forbidden by Nuremberg's particiate-controlled

council. And though painting, like the city's other trades, were

carefully regulated by the council, it was categorized as a 'liberal

art', a status enjoyed by sculptors, book printers, and engravers

as well. Although monopolistic guilds offered ordinary painters

more protection, Nuremberg's commercial structure put ambitious

painters at an advantage by favoring talent and entreprenurship.

Dürer's self-assertion thus does not represent the elevation

of artisan or handwerker to the new status of 'artist',

such as was being invented in Italy; rather, it is an attitude

made possible by, on the one hand, a modern stule of finance and

commerce developed in Nuremberg by 1500 and, on the other, the

very lack of a predetermined legal definition of what the trade

of th painter should or shoukd not be. Indeed, most local Nuremberg

painters between 1500 and 1596 were fighting precisely for the ordinary status of Handwerk so that, through guild

monopoly, they could protect their products from more talented

foreign competitors. Dürer's historical role in the development

of art as a commodity salable on the 'open' market presupposes

a particular freedom of movement between crafts (painting, engraving,

woodcutting, and printing) that was uniquely possible in his native

city.