Excerpts from Svetlana Alpers:

Rembrandt's

Enterprise: the Studio and the Market,

p. 66: Rembrandt created

his studio at the expense of an established relationship between

the household and art. The common Dutch pattern was coexistence

of art and the household. Art in Holland was a cottage industry,

a domestic production that was represented as such. The studio

was a room in the artist's house, the schilderkamer, in

which artists often depicted themselves, or  perhaps other artists,

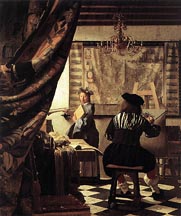

at work. Vermeer's Art of Painting, the most famous picture

of this type, can stand for the genre. Members of artists' families

served as models, and artists often painted themselves as members

of their own families --with wife and children and, on occasion,

with parents -- making paintings of them, or painting in their

midst....

perhaps other artists,

at work. Vermeer's Art of Painting, the most famous picture

of this type, can stand for the genre. Members of artists' families

served as models, and artists often painted themselves as members

of their own families --with wife and children and, on occasion,

with parents -- making paintings of them, or painting in their

midst....

p. 67 Rembrandt turns away from this.

Though he twice depicted himself with Saskia, the images do not

fit into the domestic category. In the Dresden Prodigal Son,

as we have seen, Rembrandt directly implicated his art in a disruption

of the married state....

In the Dresden Prodigal Son,

as we have seen, Rembrandt directly implicated his art in a disruption

of the married state....

How does Rembrandt manifest his ambition

in terms of the studio? One obvious pictorial sign of Rembrandt's

worldly ambitions is found in the portrait heads --mostly early

self-portraits-- bedecked with a golden chain. Since antiquity,

a chain of gold had been the sign of royal favor. And in the Renaissance,

with new claims being made for art, and with the high honor and

even urgency with which it was received at court, artists also

became the recipients of chains. They were an accepted mark of

royal favour and were sought after, won, and then often displayed

by artists in their /p. 68 self-portraits. Titian, Vasari, Rubens

(who received at least three), Van Dyck, and Goltzius were among

the artists so rewarded. Rembrandt was not, nor did he seek this

reward. There has been some difference of opinion about the precise

way in which to interpret his depiction of the chain: is it a

claim the imaginary nature of which testifies to an awareness

of the constraining and hence suspect nature of actual royal favor,

or does it perhaps call attention to the chain's symbolic force

-- an attribute in that case of the honor of art and of the artist

rather than a tribute to worldly ambition and success. Regardless

of its exact meaning, we can say that the reward that was sought

by others in the world is displaced by Rembrandt onto what is

obviously a studio trapping. These pictures are not fed by the

desire "if I only had a gold chain" but are a studio

enactment of the award with Rembrandt playing the artist's role.

The same thing might be said about those self-portraits in which

Rembrandt dons a bit of armor....

p. 88: As a master in the studio he made

himself a free individual, not beholden to patrons. But he was

beholden to the market --or more specifically to the identification

that he made between two representations of value, art, and money.

Descamps put it well when he wrote of Rembrandt that he loved

only three things: his freedom, art, and money. The relationship

or, given the the complexity of the mix, the relationships among

the three seem self-evident because they are so basic to our culture.

But my interest lies in showing that the distinctiveness of Rembrandt's

artistic production lies in his originating investment in this

system....

/p. 89: The status of the artist and his

art was a lively social and economic issue in Holland around midcentury.

Professional status was very much on the mind of Dutch artists

at just this time. Sociologists would call what was happening "professionalization." One

aspect of the professionalization of a vocation is the institutionalization of

bonds between practitioners, the claim to certain common skills, and the upholding

of standards of competence. Academies of various kinds were one means by which

professionalization was achieved by (or for) artists in Renaissance Europe. There

was much activity towards this end in the Netherlands during Rembrandt's lifetime:

a short-lived Brotherhood of Painters brought artists and writers together in

Amsterdam in 1653; a confrerie of artists replaced the Guild of St. Luke in The

Hague in the 1650s....Art historians have usually considered such professionalization

to be a means of achieving freedom for the artist and his art, freedom from the

restrictions of craft guilds. Much attention had been paid to the artistic ideals

of such groups. But these changes were not accompanied by more power in their

relationship to clients. The type of patronage in which the patron/buyer encouraged

the professional to identify with him and hence serve him socially characteristically

flourished in Europe along with the new academies. Vasari, for example, a founder

of the artists' academy in Florence, had favored an artist on the model of the

educated courtier. Wives and housewives, which had played such a central role

in Dutch art, were not part of this scheme. Vasari warns artists not to be distracted

or /p. 90: driven by wives, who on a number of occasions in the Lives are

accused of ruing a husband's career. We can see marks of the social identification

of the artist with the patron-buyer by comparing Bol's Self-Portrait with

his portrayal of other sitters: he clearly fashioned his own image after theirs.

And the stance taken in his art was confirmed in his rich marriage, which ended

his professional career as a painter....

/p.91: Rembrandt's pictorial reflection on the role of the client or interested viewer is the subject of a drawing now in New York. It differs from those images of the time which were designed to put a client's or patron's attention to art in a favorable light. A characteristic format depicted the artist at his easel in the studio entertaining an admiring visitor.  In an engraving by Abraham Bosse, the situation of the noble court artist is played off against that of the vulgar artist, who, in an engraving held up by the assistant at the right, is depicted working to support his family. Noble art practiced at court replaces drudgery at home. The court and the family are themes, and the choice between them a stance, that Rembrandt did not take up either in his life or in his art. Rather than courting /p. 92: patrons, as other artists did, Rembrandt took to castigating them: the painting in view in his drawing is surrounded by people listening to the ass-eared man with pipe at the left. (Could the man ostentatiously shitting and wiping his seat at the right-- a traditional figure from peasant kermis scenes-- be a joke agains those who compared Rembrandt's paint to dung?) Instead of being a counterattack by a man on the defense as Schwartz has suggested, Rembrandt's drawing enthusiastically enters the fray....

In an engraving by Abraham Bosse, the situation of the noble court artist is played off against that of the vulgar artist, who, in an engraving held up by the assistant at the right, is depicted working to support his family. Noble art practiced at court replaces drudgery at home. The court and the family are themes, and the choice between them a stance, that Rembrandt did not take up either in his life or in his art. Rather than courting /p. 92: patrons, as other artists did, Rembrandt took to castigating them: the painting in view in his drawing is surrounded by people listening to the ass-eared man with pipe at the left. (Could the man ostentatiously shitting and wiping his seat at the right-- a traditional figure from peasant kermis scenes-- be a joke agains those who compared Rembrandt's paint to dung?) Instead of being a counterattack by a man on the defense as Schwartz has suggested, Rembrandt's drawing enthusiastically enters the fray....

/p. 93: ...[W]e can try to describe Rembrandt's

behavior in terms of the marketplace. Let us begin by considering what kinds

of marketing options were available to artists at /p. 94: the time. We shall

take up some materials from the previous chapter, but here with an emphasis

on the marketing of art rather than the career of the artist.

It has long been said --our sources go back to the seventeenth century itself--that

what was remarkable about the Dutch taste for paintings is that the production

demand were so large and marketing so widespread. Producing for the open market

was the rule rather than exception for the great majority of Dutch artists

in Rembrandt's day. Lacking land, wrote one traveler, everyone in the Netherlands

invested in pictures....

We know there were exceptions to this common production and marketing situation.

There were paintings ordered, for example, by the court, by burgomasters for

town halls, and by regents of various organizations for their buildings. Families

ordered portraits for their domestic walls. Artists found alternatives to

producing for the open market. Lievens, Bol, and Flinck each worked himself

into a circle of moderately dependable patrons....

p. 96: While he [Rembrandt] turned against the patronage system, he did not

embrace the market in its traditional form but rather felt his way towards

finding a place for art in the operations of the developing capitalist marketplace....

p. 97: An economy with its attendant notion of service, characterized his

relationship to clients, Rembrandt was evidently more comfortable circulating

his paintings by conducting negotiations with creditors than by serving patrons....

p.101: What did Rembrandt have in mind in place of the patronage system?

It seems to have been something a bit old but also rather new: a craftsman

selling his products replaced by an entrepreneur, of sorts, working the market

with pictures distinctive in manner or mode. Two terms deserve attention here:

entrepreneur and market. I say "an entrepreneur of sorts." As far as production

went, it was Rubens and not Rembrandt who was the prime innovator in the north

of Europe at the time. Though Rembrandt's obsession with the intricacies

of the market system permeated his life and his work, the organization of his

shop --a master surrounded by student-assistants each eventually producing

paintings on other own for sale--was an established one. It was Rubens, but

contrast, who promoted a division of labor. He developed a painting factory:

assistants specialized in certain skills--landscapes, animals, and so on--

and the master devised a mode of invention employing a clever combination of

oil sketches and drawings. These permitted his inventions to be executed by

others, sometimes with final touches to hands or faces by the master himself.

It is in keeping with the logic of this factory procedure that Rubens, unlike

Rembrandt, did not sign the works that were sold from his studio. Only five

of the thousands of works produced were signed. On occasion, when challenged

or pressed, Rubens agreed to make distinctions between hands. But the claim

that all works issuing forth from his studio were his was a claim about a commodity

whose value was distinguishable from his own hand and which was capable of

proliferation and replication. Rubens confirmed this expansive notion of authenticity

and authentication when he sought and received copyright protection against

pirating of th engraviings which his studio was in the business of producing

after his paintings. Rembrandt imitated this mode in a brief experiment with

essentially replicative etchings in the thirties, but he then gave it up. Modern

attempts to separate works by Rubens's hand from those by others in the studio,

and the taste for his eigenhändig oil sketches, intrude a notion

of value inappropriate to his mode of production and to the commodity he produced.

Though he was himself a brilliant wielder of both brush and pen, Rubens was

a pioneer in encouraging the distribution and sales of his inventions through

means that have come, in our age, to be called mechanical reproduction. For

all its moder- /p. 102:nity in these terms, it did not prove to be a lasting

model for art in our culture.

While Rubens's interest was in the work of art as a commodity distinct from

himself personally, Rembrandt, despite the diffusion of his manner in his studio,

was unwilling to make this separation. So far as we know he almost never collaborated

on paintings with assistants. His merging of invention with execution, his

distinctive handling of the paint (or of the etched line), his invention and

use of his signature presented his works and those of his studio as an extension

of himself. Related to this is the fact that, whil Rubens's works benefited

from and frankly displayed the fact that they did cleave to pictorial tradition,

Rembrandt's, as we have seen, did not. But this was where Rembrandt's peculiarity

and innovation lay. It was the commodity --the Rembrandt-- that

Rembrandt made that was new. And it is he, not Rubens, who invented the work

of art most characteristice of our culture-- a commodity distinguished among

others by not being factory produced, but produced in limited numbers and creating

its market, whose special claim to the aura of individuality and to high market

value binds it to basic aspects of an entrepreneurial (capitalist) enterprise....

p. 105: A gold chain awarded for royal service was considered a sign of honor

in this system. Honor was attributed to the artist's person and set against

goods or wealth, or profit on the market. But Rembrandt behaved in a way that

upset this system of values and the distinctions it strove to preserve: he

pursued honor not in the sense of honors that /p. 106: other could confer,

but in the sense of what art itself could confer, the value that his art itself

brought into being, and this was registered in the money values of the market.

This was the way the world paid tribute to art, the way the artist exacted

its tribute --the ambiguity of the word, again here, not offered lightly.

The concept of honor has a complicated history, but one constant has been

that honor was set against the pursuit of riches in trade. In the sixteenth

century, Calvinists, taking up an established humanist position, addressed

the phrase as a warning to merchants. As an admonition, it called attention

to the difference between the material things of the world (gold, possessions)

and a superior moral goal or sphere (honor). But the notion of honor was complicated

by the fact that though considered to be a man's possession, it was a possession

bestowed by others: you had to, in other words, gain it. With the domination

of the marketplace in seventeenth-century Holland and in England, it is not

surprising that a prophet of the market economy like Hobbes, in his Leviathan of

1651, should collapse the distinction between honor and the market and see

the first in terms of the second: it is in the marketplace that honor is gained,

or in Hobbes's works, "The Value, or WORTH of a man, is as of

all other things, his Price," and, "The manifestation of the Value we set on

one another, is that which is commonly called Honouring and Dishonouring...." [T]he nature of his [Rembrandt] dealings on the art market....provide sufficient

evidence to suggest that it was in this new sense of market worth that Rembrandt

pursued honor for art.

We have been considering some of the evidence about Rembrandt's behavior in

relationship to the marketplace -- the first point being that he treated it

as an alternative to the patronage system for securing the economic well-being

of his art. The marketplace has been invoked not only as a locus for his life, but also because the economic system to which it was central offers an appropriate model to use in understanding Rembrandt and his art. It was a model that Rembrandt himself can be said to have taken up: in remarkable ways he internalized into his practice this system of which he was part. He did this in a manner that was at once canny and naive: /p. 107: canny in that he devised representations so adequate to its values, naive in that in the very devising of the representations he never lost his faith either in them or in the system of which they were part. The description of Rembrandt as pictor economicus is a construction, then, but it was a construction he put on himself....

Exchange was said to characterize relations between men, whose nature was defined by an interest in the acquisition of goods (wealth). A human equalizer, the market economy so defined freed men from the social bonds or heirarchy of the previous society, where property had taken the immovable form of land, where men produced only what they needed to subsist, and where the order was social (man to man), rather than economic (man to goods). On the open market men could deal with other men through the impersonal and highly flexible medium of credit and the system of exchange....

p. 108: But if Rembrandt sought to establish the value of his painting on the marketplace, we must establish what value on the marketplace means. Market value is admittedly a very slippery, an economist today might say a contradictory, notion, since value is tantamount to market price. In effect, all prior or intrinsic notions of value are replaced by a system in which value is absorbed into that relative worth established in the exchange between goods; value is simply the amount for which a thing can be exchanged, the market price. Value is considered to be a social or a human construct produced in a relational system activated by human desires....

p. 114: Rembrandt and individualism (or Rembrandt and the individual) has become a commonplace in the literature on him. Here, for example, is Julius Held: "Rembrandt himself never yielded his personal independence. The greatness of his art, in the last analysis, is due to this fact: that it is the work of a man who never compromised, who never permitted himself to be burdened with a chain of honor, and fiercely maintained both the integrity of his art and his freedom as a man." This is not wrong, but the terms which are brought together here are unexamined. How is it that art should have come to be so identified with what are called the freedom and the self of the artist? Historically, the argument for the self, the definition of the sense in which a person is considered, or considers himself or herself to be, an individual, has taken many different forms. In Rembrandt's case alone, religion, philosophy, and the poets have all been appealed to on one occasion or other. In the previous chapter I proposed that the invention of the individuality "effect" of his works was a function of the authority Rembrandt exercised in the studio. But I want now to add that it was also a function of the economic system in which he lived and in which he /p.115: played such an active part. It was in Rembrandt's time that the individual came to be defined in what were then new, economic terms. Those familiar words from the American declaration of human rights, "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," are a reworking of Locke's "life, liberty, and estate" which constituted his definition of property: "By property I must be understood...to mean that Property which Men have in their Persons as well as Goods." On this view, to be an individual is defined by the right to property. And the most essential property right of each man, and hence the grounding of this notion of the individual, curious though it might sound put in this form, is the right to property in one's own person. Freedom, then, is defined as proprietorship in and of one's own person and capacities. It is the proprietorial quality of this notion of the individual to which I wish to call attention. It was Rembrandt who made this the center of his art --the center, even, of Art.

The paradigmatic manifestation of this is Rembrandt's production of self-portraits --not as they started out, but particularly as they came to be produced after the hiatus between 1640 and 1648. The later self-portraits no longer serve as studies of expressive heads, lighting, and costume. Even the few studio accoutrements of the earlier works --gold chains, feathered hats, armor-- are absent, as Rembrandt appears to concentrate harder, to zero in, on himself. We speak of these late works as having or displaying depth, as if their difference is determined by Rembrandt looking deeper into himself. But it is intead a matter of surface, in the sense that he dwells on himself in paint. It is not that Rembrandt looks deeper into himself, but that he closes in --identifying self, himself, with his painting. The embodiment characteristic of many of the later works --not only the thickness of the paint but the congruence between paint and flesh as we see it in the Lucretia, the Claudius Civilis, The Slaughtered Ox, and the Self-Portrait with the Dead Bittern-- comes to be the rooting of identity in the painting itself.

One could put Rembrandt's representation of himself into words: I paint (or I am painting), therefore I am. When Rembrandt returned to self-portrayal in 1648 after a break of eight years, it was by etching himself as an artist, drawing (perhaps etching) by a window. After 1648 almost all of his self-portraits were executed in paint. And in the Kenwood, Louvre, and Cologne paintings, Rembrandt for the first time paints himself as the artist at work, dressed in studio garb. Occurring when it does in his production of self-portraits, this is less a matter of taking up an /p.116: established subgenre of portraiture, or taking on yet another "role," that of the artist, than a matter of taking himself up in a definitive compound with paint. He is not defining himself professionally as a painter, but defining the self in paint.

Portraits of artists --made both by or of them-- proliferated in the Netherlands. Although they account for only a small percentage of such works, the paintings commissioned by kings and princes were in many respects exemplary of the type, and the Medicis' famous gallery of artist's self-portraits is representative of the interest in them that princes had. Their requests might specify, as the Medici agent did to Mieris, that the artist paint himself in the process of painting or holding some work with figures by the painter's hand. In self-portraits of this type, the established order was defined and confirmed: the servant of the prince delivered an image of himself which served a certain social order and a certain notion of art. This stance also informs other artists' portraits: self-portraits that were done for paterons other than princes; portraits of the artist at work, such as the Dutch pictures which show the artist by his easel with a musical instrument (these are not necessarily self-portraits); and those artists' self-portraits which make no reference to the profession, but accomodate to other social institutions such as the family. Rubens, who painted himself most unwillingly, did so only for a king, in friendship, or in marriage. Even when a self-portrait was done out of friendship, as witness Poussin's self-portraits for Pointel and Chantelou, it entertained the ambition to offer a definition of Art and of the status of the artist. On this point iconographic studies are correct. It is less the diverse notions of the artist and of art than the fact that such notions were generally in play to which I wish to call attention.

perhaps other artists,

at work. Vermeer's Art of Painting, the most famous picture

of this type, can stand for the genre. Members of artists' families

served as models, and artists often painted themselves as members

of their own families --with wife and children and, on occasion,

with parents -- making paintings of them, or painting in their

midst....

perhaps other artists,

at work. Vermeer's Art of Painting, the most famous picture

of this type, can stand for the genre. Members of artists' families

served as models, and artists often painted themselves as members

of their own families --with wife and children and, on occasion,

with parents -- making paintings of them, or painting in their

midst....