Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 220

Orientalism and the Abu Ghraib Pictures

|

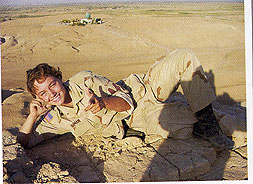

The pictures above were part of the series of pictures taken by Specialist Sabrina Harman at Abu Ghraib prison. They are a powerful juxtaposition to the nineteenth images of Orientalism. These photographs were included in an article on the Abu Ghraib pictures that appeared in The New Yorker: Philip Gourevitch and Errol Morris," Exposure: The Woman behind the camera at Abu Ghraib," March 24, 2008, pp. 44-57.

Consider the following excerpt from the Gourevitch and Morris article in relationship to our discussion of Orientalism:

p. 52: "I was trying to expose what was being allowed" --that phrase again--"what the military was allowing to happen to other people," Harman said. In other words, she want to expose a policy; and by assuming the role of a documentarian she had found a way to ride out her time at Abu Ghraib without having to regard herself as an instrument of that policy. But it was not merely her choice to be a witness to the dirty work on Tier 1A: it was her role. As a woman, she was not expected to wrestle prisoners into stress positions or otherwise overpower them but, rather, just by her presence, to amplify their sense of powerlessness. She was there as an instrument of humiliation. The M.P.s knew very little about their Iraqi prisoners or the culture they came from, but at Fort Lee, before being deployed, they were given a session of /p. 54:"cultural awareness" training, from which they'd taken away the understanding--constantly reinforced by M.I. handlers-- that Arab men were sexual prudes, with a particular hangup about being seen naked in public, especially by women. What better way to break an Arab, then, than to strip him, tie him up, and have a woman laugh at him? Taking pictures may have seemed an added dash of mortification, but to Harman it was a way of deflecting her own humiliation in the the transaction, by acting as a spectator.

Viewpoint: Power of abuse pictures

Photographer has become abuser in Abu Ghraib

(Article appeared in BBC News World Edition, May 13, 2004)

Award-winning British photographer and documentary filmmaker David Modell explores the particular, destructive power of the pictures of US soldiers abusing Iraqi prisoners.

The language of photography has, again, proved its power.

The person who said that "a picture is worth a thousand words" was wrong - they missed the point.

Photography is a language, a form of communication in its own right that doesn't bear comparison with any other.

There is no form of words - even if describing the horror these pictures reveal - that could have elicited the kind of response felt when looking at them and the political shift that will follow.

Remembering images

A photograph speaks to all of us regardless of culture or spoken language.

There is a synchronicity between the nature of a still image and the way in which we remember events.

There is something unique about the language of photography that contributes to the horror of these pictures

Memory itself is constructed through frozen moments in time and so a photograph slips serenely into our minds and is retained. I do not have the picture in front of me, yet I can see clearly the gentle, almost pre-pubescent body of the female GI loosely holding the dog lead, head turned, her other arm relaxed - held slightly away from her torso. And I can see the writhing man on the other end, naked and destroyed.

Moving images can never be this potent. We cannot retain and carry with us a video-clip in the same way.We cannot have a two-minute news report always available in the top drawer of our minds ready to be glanced at, at any moment.

Triangular relationship

There is something else though, unique about the language of photography that contributes to the horror of these pictures.

Photographically, the pictures are of the highest standard.

I don't mean that they are technically good. But they are extraordinary examples of what photographers always strive to achieve - a triangular relationship between subject, viewer and author.

Unlike most appalling images of suffering they are not taken by a sympathetic journalist driven by a need to inform.

Normally we can draw some comfort in looking at distressing photographs because, as viewer, we are receiving the message communicated by the photographer- that what he or she is witnessing is unacceptable and upsetting.

We look at the picture and say yes, I agree, I understand the message.

We can identify with the victim and with the photographer's response to what they saw. We can feel that, in simply viewing the image we are playing our part in helping the victim.

Photographer as abuser

The pictures from Abu Ghraib are fundamentally different.

These are not snatched, clandestine images, taken to uncover the truth and disseminate it.

In the almost perfect compositions it is obvious that they were taken in a perversely relaxed atmosphere- emphasised by the demeanour of the troops.

And this reveals an appalling reality - that photographs are a deliberate part of the torture.

The taking of the pictures was supposed to compound the humiliation and sense of powerlessness of the victims.

The photographer was the abuser.

When we view the pictures, we are forced to play our part in this triangle of communication.

The photographs were taken to abuse, by exposing the victim at their most vulnerable.

By looking at the images we become complicit in the abuse itself.

It is this that makes them intolerable for the viewer and why they are so destructive to a war effort built on the spin of "liberation".