ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments

Images of Authority I

We are all aware of the dramatic shots from April 13, 2003 just after the American troops gained control of Baghdad of the Iraqis with the help of American troops pulling down the statue of Saddam Hussein. This literal overthrow of the statue and defacement of other images is an action regularly repeated throughout human history when a hated leader is deposed. In Rome when a hated Emperor was deposed his images were literally defaced or recut. The Romans called this ritual damnatio memoriae.

The Emperor Domitian Setting out, relief from the Cancelleria, Rome, 80-90 AD. The head of Domitian, the fourth figure on the left, was recarved as a portrait of his successor Nerva after Domitian suffered damnatio memoriae. On the left hand side of the panel are images of the gods Mars and Minerva. The Emperor is followed by the goddess Roma and the genius of the Roman Senate (a personification of that body). |

Leaders have long seen the power of images. From Ancient Egypt with the images of the Pharaoh to the images of George W. Bush in government offices, the image of the political leader has been understood to signify the authority of that leader. In Roman culture, newly elected Emperors regularly sent their images throughout the Empire. A statue of the Emperor in a city asserted the political domination of that Emperor. An image of the Emperor was understood to participate in the power of the actual man. Any act of violence towards the image was treated like an action against the physical person of the Emperor. Saddam Hussein was clearly aware of the role statues and other representations of himself played in asserting his claim to authority. The Iraqis action of hitting the statues of Saddam with their shoes was clearly based on the insult this action signified against a person [see the incident of throwing shoes at President Bush]. Iraqi artist Zerak Mera created the following statue from Iraqi army boots in the center of Kirkuk where a statue of toppled Iraqi president Saddam Hussein once stood.

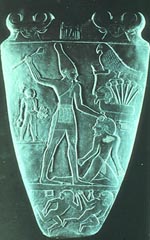

The longevity and the central role these images of political authority have played in human history make this a logical topic to begin our discussion of Art and Politics. Histories of Western Art regularly begin with accounts of Sumerian or Egyptian Art. Civilization is frequently understood to have begun in these river cultures --the Tigris and Euphrates in Sumeria and the Nile in Egypt. When I teach the Survey course, the first major work I consider is the so-called the Palette of King Narmer, dating from c. 3000-2920 BCE When compared to earlier works like a Tomb painting from Hierakonpolis, the palette represents a fundamental mutation in art. This mutation can be directly connected to the crucial political transformation that had occurred in Egypt with the unification of the Nile under the central authority of the Pharaoh. The relief commemorates the victory of the region to the south, Upper Egypt over the region to the north, Lower Egypt.

Palette of King Narmer, c. 3000 BCE |

||

In 2334 BCE, the loosely linked group of cities known as Sumer came under the control of a great king, Sargon of Akkad (if that sounds like the Lord of the Rings, consider that Tolkien was very much aware Ancient Near Eastern culture just as the culture of the Middle Ages, and the story of a great king subduing independent groups was central to his "mythology"). Sargon's grandson, Naram-Sin set up a victory stele at Sippar to commemorate his victory over the Lullubi, a people from the Iranian mountains to the east.

The Palette of King Narmer and the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin present striking parallels. Both are designed to commemorate important military victories, and both can be seen as statements of the authority of a leader. As visual images they can be "read" as statements of political authority. Try to "read" these images. Note the different techniques and conventions that the artists employ to make their respective statements. Record your responses in your journals.

An important figure in the history Mesopotamia is the Babylonian king, Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE). Noted for his military conquests, Hammurabi is also famous for his Law Code by which he ruled the centralized government of southern Mesopotamia. He wrote that the intention of the law code was "to cause justice to prevail in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil, that the strong might not oppress the weak." This code is recorded on a basalt stele now in the Louvre in Paris:

Detail of stele of Hammurabi: Shamash, the supreme sun god and judge, offers to Hammurabi the rod and ring that symbolize authority. These symbols are apparently derived from builders' tools --measuring stick and coiled rope. The implication is that the king is to build social order. The reference to builders' tools reminds us of the importance of building as another means of giving physical testimony to a ruler's power. The stele thus asserts the divine sanction of Hammurabi's power, and that the social order he constructs is a reflection of a divine order. |

The works considered here clearly illustrate the importance of the close relationship between political and religious authority in ancient cultures. Consider the parallels between these and the Old Testament story of Moses.