Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 220

Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity

Excerpts from Griselda Pollock, "Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity," in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, London, 1988:

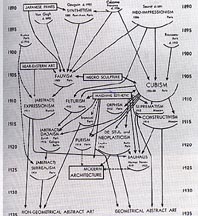

/p. 50:...The schema which decorated the cover of Alfred H. Barr's catalogue for the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1936 is paradigmatic of the way modern art has been mapped by modernist art history. Artistic practices from the late nineteenth century are placed on a chronological flow chart where movement follows movement connected by one-way arrows which indicate influence and reaction. Over each movement a named artist presides. All those canonized as the initiators of modern art are men. Is this because there were no women involved in early modern movements? No. Is it because those who were, were without significance in determining the shape and character of modern art? No. Or is it rather because what modernist art history celebrates is a selective tradition which normalizes, as the only modernism, a particular and gendered set of practices? I would argue for this explanation. As a result any attempt to deal with artists in the early modern history of modernism who are women necessitates a deconstruction of the masculinist myths of modernism./p. 51:

|

These are, however, widespread and structure the discourse of many counter-modernists, for instance in the social history of art. The recent publication The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, by T.J. Clark, offers a searching account of social relations between the emergence of new protocols and criteria for painting --modernism-- and the myths of modernity shaped in and by the new city of Paris remade by capitalism during the Second Empire..../p.52: Modernity is presented [by Clark] as far more than a sense of being 'up to date' --modernity is a matter of representations and major myths --of a new Paris for recreation, leisure and pleasure, of nature to be enjoyed at weekends in suburbia, of the prostitute taking over and of fluidity of class in the popular spaces of entertainment. The key markers in this mythic territory are leisure, consumption, the spectacle and money. And we can reconstruct from Clark a map of Impressionist territory which stretches from the new boulevards via Gare St Lazare out on the suburban train to La Grenouillère, Bougival or Argenteuil. In these sites, the artists lived, worked and pictured themselves. But in two of the four chapters of Clark's book, he deals with the problematic of sexuality in bourgeois Paris and the canonical paintings are Olympia, 1863 and A Bar at the Follies-Bergère, 1881-2.

|

|

It is a mighty but flawed argument on many levels but here I wish to/ p.53: attend to its peculiar closures on the issue of sexuality, For Clark the founding fact is class. Olympia's nakedness inscribes her class and thus debunks the mythic classlessness of sex epitomized in the image of the courtesan. The fashionably blasé barmaid at the Folies evades a fixed identity as either bourgeois or proletarian but none the less participates in the play around class that constituted the myth and appeal of the popular.

Although Clark nods in the direction of feminism by acknowledging that these paintings imply a masculine viewer/consumer, the manner which this is done ensures the normalcy of that position leaving it below the threshold of historical investigation and theoretical analysis. To recognzie the gender specific conditions of these paintings' existence one needs only imagine a female spectator and a female producer of the works. How can a woman relate to the viewing positions proposed by either of these paintings? Can a woman be offered, in order to be denied, imaginary possession of Olympia or the barmaid? Would a woman of Manet's class have a familiarity with either of these space and its exchanges which could be evoked so that the painting's modernist job of negation and disruption could be effective? Could Berthe /p. 54: Morisot have gone to such a location to canvass the subject? Would it enter her head as a site of modernity as she experienced it? Could she as a woman experience modernity as Clark defines it at all?

|

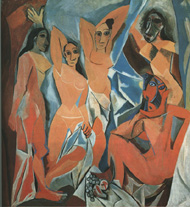

For it is a striking fact that many of the canonical works held up as the founding monuments of modern art treat precisely with this area, sexuality, and this form of it, commercial exchange. I am thinking of innumerable brothel scenes through to Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon or that other form, the artist's couch. The encounters pictured and imagined are those between men who have the freedom to take their pleasures in many urban spaces and women from a class subject to them who have to work in those spaces often selling their bodies to clients, or to artists. Undoubtedly these exchanges are structured by relations of class but these are thoroughly captured within gender and its power relations. Neither can be separated or ordered in a hierarchy. They are historical simultaneities and mutually inflecting.

So we must enquire why the territory of modernism so often is a way of dealing with masculine sexuality and its sign, the bodies of women --why the nude, the brothel, the bar? What relation is there between sexuality, modernity and modernism. If it is normal to see paintings of women's bodies as the territory across which men artists claim their modernity and compete for leadership of the avant-garde, can we expect to rediscover paintings by women in which they battled with their sexuality in the representation of the male nude? Of course not; the very /p. 55: suggestion seems ludicrous. But why? Because there is a historical asymmetry --a difference socially, economically, subjectively between being a woman and being a man in Paris in the late nineteenth century. This difference --the product of the social structuration of sexual difference and not any imaginary biological distinction --determined both what and how men and women painted.

I have long been interested in the work of Berthe Morisot (1841-96) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), two of the four women who were actively involved with the impressionist exhibiting society in Paris in the 1870s and 1880s... But how are we to study the work of artists who are women so that we can discover and account for the specificity of what they produced as individuals while also recognizing that, as women, they worked from different positions and experiences from those their colleagues who were men?

Analysing the activities of women who were artists cannot merely involve mapping women on to existing schemata even those which claim to consider the production of art socially and address the centrality of sexuality. We cannot ignore the fact that the terrains of artistic practice of art history are structured in and structuring of gender power relations....

[A] major aspect of the feminist project [is] the theorization/ p. 56: and historical analysis of sexual difference. Difference is not essential but understood as a social structure which positions male and female people asymmetrically in relation to language, to social and economic power and to meaning. Feminist analysis undermines one bias of patriarchal power by refuting the myths of universal or general meaning. Sexuality, modernism and modernity cannot function as given categories to which we add women. That only identifies a partial and masculine viewpoint with the norm and confirms women as other and subsidiary. Sexuality, modernism or modernity are organized by and organizations of sexual difference. To perceive women's specificity is to analyse historically a particular configuration of difference.

This is my project here. How do the socially contrived orders of sexual difference structure the lives of Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot? How did that structure what they produced? The matrix I shall consider here is that of space.

Space can be grasped be grasped in several dimensions. The first refers us to spaces as locations. What spaces are represented in the paintings made by Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt? And what are not? A quick list includes:

The majority of these have to be recognized as examples of private areas or domestic space. But there are paintings located in the public domain, scenes for instance of promenading, driving in the park, being at the theatre, boating. They are the spaces of bourgeois recreation, display, and those social rituals which constituted polite society....

On closer examination, it is much more significant how little of typical impressionist iconography actually reappears in the works made by artists who are women. They do not represent the territory which their colleagues who were men so freely occupied and made use of in their works, for instance bars, cafés, backstage and even those places which Clark has seen as participating in the myth of the popular --such as the bar at the /p. 62 Folies Bergère or ven the Moulin de la Galette. A range of places and subjects was closed to them while open to their male colleagues who could move freely with men and women in the socially fluid public world of the streets, popular entertainment and commercial or casual sexual exchange.

The second dimension in which the issue of space can be addressed is that of the spatial order within paintings. Playing with spatial structures was one of the defining features of early modernist painting in Paris, be it Manet's witty and calculated play upon flatness or Degas's use of acute angles of vision, varying viewpoints and cryptic framing devices. ...[A]lthough there are examples of their using similar tactics, I would like to suggest that spatial devices in the work of Morisot and Cassatt work to a wholly different effect.

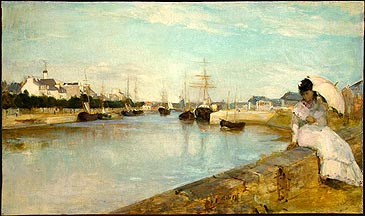

A remarkable feature in the spatial arrangements in paintings by Morisot is the juxtaposition on a single canvas of two spatials systems -- or at least two compartments of space often obviously boundaried by some device such as a balustrade, balcony, veranda or embankment whose presence is underscored by facture.

|

In The Harbour at Lorient, 1869, Morisot offers us at the left a landscape view down the estuary represented in traditional perspective while in one corner, shaped by the boundary of the embankment, the main figure is seated at an oblique angle to the view and to the viewer....

|

In On the Balcony, 1872, the viewer's gaze over Paris is obstructed by the figures who are none the less separated from that Paris as they look over the balustrade from the Trocadéro, very near to her home.

|

The point can be underlined by contrasting the painting by Monet, The garden of the princess (1867), where the viewer cannot readily imagine the point from which the painting has been made, namely a window high in one of the new apartment buildings, and instead enjoys a fantasy of floating over the scene. What Morisot's balustrades demarcate is not the boundary between public and private but between spaces of masculinity and of femininity inscribed at the level of both what spaces are open to men and women and what relation a man or woman has to that space and its occupant./ p.63:

In Morisot's paintings, moreover, it is as if the place from which the painter worked is made part of the scene creating a compression or immediacy in the foreground spaces. This locates the viewer in that same place, establishing a notional relation between the viewer and the woman defining the foreground, therefore forcing the viewer to experience a dislocation between her psace and that of a world beyond its frontiers....

/p. 64: In the case of Mary Cassatt I would now want to draw attention to the disarticulation of the conventions of geometric perspective which had normally governed the representation of space in European painting since the fifteenth century. Since its development in the fifteenth century, this mathematically calculated system of projection had aided painters in the representation of a three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface by organizing objects in relation to each other to produce a notional and singular position form which the scene is intelligible. It establishes the viewer as both absent from and indeed independent of the scene while being its mastering eye/I.

/p. 65: It is possible to represent space by other conventions. Phenomenology has been usefully applied to the apparent spatial deviations of the work of Van Gogh and Cézanne. Instead of pictorial space functioning as a notional box into which objects are placed in a rational and abstract relationship, space is represented according to the way it is experienced by a combination of touch, texture, as well as sight. Thus objects are patterned according to subjective hierarchies of value for the producer. Phenomenological space is not orchestrated for sight alone but by means of visual cues refers to other sensations and relations of bodies and objects in a lived world. As experiential space this kind of representation becomes susceptible to different ideological, historical as well as purely contingent, subjective inflections.

|

These are not necessarily unconscious. For instance in Young girl in a blue armchair, 1878 by Cassatt, the viewpoint from which the room has been painted is low so that the chairs loom large as if imagined from the perspective of a small person placed amongst massive upholstered obstactles. The background zooms sharply away indicating a different sense of distance from that a taller adult would enjoy over the objects to an easily accessible back wall. The painting therefore not only pictures a small child in a room but evokes that child's sense of the space of the room. It is from this conception of the /p. 66: possibilities of spatial structure that I can now discern a way through my earlier problem to relate space and social processes. For a third approach lies in considering not only the spaces represented, or the spaces of representation, but the social spaces from which the representation is made and its reciprocal positionalities. The producer is herself shaped within a spatially orchestrated social structure which is lived at both psychic and social levels. The space of the look at the point of production will to some extent determine the viewing position of the spectator at the point of consumption. This point of view is neither abstract nor exclusively personal, but ideologically and historically construed. It is the art historian's job to recreate it --since it cannot ensure its recognition outside its historical moment.

The spaces of femininity operated not only at the level of what is represented, the drawing-room or sewing-room. The spaces of femininity are those from which femininity is lived as a positionality in discourse and social practice. They are the product of a lived sense of social locatedness, mobility and visibility, in the social relations of seeing and being seen. Shaped within the sexual politics of looking they demarcate a particular social organization of the gaze which itself works back to secure a particular social ordering of sexual difference. Femininity is both the condition and the effect.

How does this relate to modernity and modernism? As Janet Wolff has convincingly point out, the literature of modernity describes the experience of men. It is essentially a literature about transformations in the public world and its associated consciousness. It is generally agreed that modernity as a nineteenth-century phenomenon is product of the city. It is a response in a mythic or ideological form to the new complexities of a social existence passed among strangers in an atmosphere of intensified nervous and psychic stimulation, in a world ruled by money and commodity exchange, stressed by competition and formative of an intensified individuality, publicly defended by a blasé mask of indifference but intensely 'expressed' in a private, familial context....

/p. 67: One of the key figures to embody the novel forms of public experience of modernity is the flâneur or impassive stroller, the man in the crowd.... The flâneur symbolizes the privilege or freedom to move about the public arenas of the city observing never interacting, consuming the sights through a controlling but rarely acknowledged gaze, directed as much at other people as at the goods for sale. The flâneur embodies the gaze of modernity which is both covetous and erotic.

But the flâneur is an exclusively masculine type which functions within the matrix of bourgeois ideology through which the social spaces of the city were reconstructed by the overlaying of the doctrine of separate spheres on to the division of public and private which became as a result a gendered division. In contesting the dominance of the aristocratic social formation they were struggling to displace, the emergent bourgeoisies of the late eighteenth century refuted a social system based on fixed orders of rank, estate and birth and defined themselves in universalistic and democratic terms. The pre-eminent ideological figure is MAN which immediately reveals the partiality of their democracy and universalism. The rallying cry, liberty, equality and fraternity (again note its gender partiality) imagines a society composed of free, self-possessing male individuals exchanging with equal and like. Yet the economic and social conditions of the existence of the bourgeoisie as a class are structurally founded upon inequality and difference in terms both of socio-economic categories and of gender. The ideological formations of the bourgeoisie negotiate these contradictions by diverse tactics. One is the appeal to an imaginary order of nature which designates as unquestionable the hierarchies in which women, children, hands and servants (as well as other races) are posited as naturally different from and subordinate to white European man. Another formation endorsed the theological separation of spheres by fragmentation of the problematic social world into separated areas of gendered activity. This division took over and reworked the eighteenth-century compartmentalization of the public and private. The public sphere, defined as the world of productive labour, political decision, government, education, the law and public service, increasingly became exclusive to men. The private sphere was the world, home, wives, children, and servants....

/p. 68: Woman was defined by this other, non-social space of sentiment and duty from which money and power were banished. Men, however, moved freely between the spheres while women were supposed to occupy the domestic space alone. Men came home to be themselves but in equally constraining roles as husbands and fathers, to engage in affective relationships after a hard day in the brutal, divisive and competitive world of daily capitalist hostilities....

As both ideal and social structure, the mapping of the separation of the spheres for women and men on to the division of public and private was powerfully operative in the construction of a specifically bourgeois way of life....

/p. 69: The public and private division functioned on many levels. As a metaphorical map in ideology, it structured the very meaning of the terms masculine and feminine within its mythic boundaries. In practice as the ideology of domesticity became hegemonic, it regulated women's and men's behaviour in the respective public and private spaces. Presence in either of the domains determined one's social identity and therefore, in objective terms, the separation of the spheres problematized women's relation to the very activities and experiences /p. 70: we typically accept as defining modernity....

These territories of the bourgeois city were however not only gendered on a male / female polarity. They became the sites for the negotiation of gendered class identities and class gender positions. The spaces of modernity are where class and gender interface in critical ways, in that they are the spaces of sexual exchange. The significant spaces of modernity are neither simply those of masculinity, nor are they those of femininity which are as much the spaces of modernity for being the negative of the streets and bars. They are, as the canonical works indicate, the marginal or interstitial spaces where the fields of the masculine and feminine intersect and structure sexuality within classed order.

The Painter of Modern Life

One text above all charts this interaction of class and gender. In 1863 Charles Baudelaire published in Le Figaro an essay entitled 'The painter of modern life'. In this text the figure of the flâneur is modified to become the modern artist while at the same time the text provides a mapping of Paris marking out the sites/sights for the flâneur/artist. The essay is ostensibly about the work of a minor illustrator Constantin Guys but he is only a pretext for Baudelaire to wean an elaborate and impossible image of his ideal artist who is a passionate lover of crowds, and incognito, a man of the world.

| The crowd is his element as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the /p. 71: infinite. To be away from home and yet feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world and to be the centre of the world and yet remain hidden from the world-- such are a few of the slightest pleasures of those independent, passionate, impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince and everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family. |

The text is structured by an opposition between home, the inside of the domain of the known and constrained personality and the outside, the space of freedom, where there is liberty to look without being watched or even recognized in the act of looking. It is the imagined freedom of the voyeur. In the crowd the flâneur/artist sets up home. Thus the flâneur/artist is articulated across the twin ideological formations of modern bourgeois societing -- splitting of private and public with its double freedom for men in the public space, and the pre-eminence of a detached observing gaze, whose possession and power is never questioned as its basis in the hierarchy of the sexes is never acknowledged. For as Janet Wolff has recently argued, there is no female equivalent fo the quintessential masculine figure, the flâneur; there is not, and could not be a female flâneuse.

Women did not enjoy the freedom of incognito in the crowd. There were never positioned as the normal occupants of the public realm. They did not have the right to look, to stare, scrutinize or watch. As the Baudelairean text goes on to show, women do not look. They are positioned as the object of the flâneur's gaze.

|

Woman is for the artist in general...far more than just the female of man. Rather she is divinity, as star...a glittering conglomeration of all the graces of nature, condensed into a single being; an object of keenest admiration and curiosity that the picture of life can offer to its contemplator. She is an idol, stupid perhaps, but dazzling and bewitching.... Everything that adorns women that serves to show off her beauty is part of herself... No doubt woman is sometimes a light, a glance, an invitation to happiness, sometimes she is just a word. |

Indeed woman is just a sign, a fiction, a confection of meanings and fantasies. Femininity is not the natural condition of female persons. It is a historically variable ideological construction of meanings for a sign W*O*M*A*N which is produced by and for another social group which derives its identity and imagined superiority by manufacturing the spectre of this fantastic Other. WOMAN is both an idol and nothing but a word. Thus when we come to read the chapter of Baudelaire's essay /p. 72 titled 'Women and prostitutes' in which the author charts a journey across Paris for the flâneur/artist, where women appear merely to be there as spontaneously visible objects, it is necessary to recognize that the text is itself constructing a notion of WOMAN across a fictive map of urban spaces --the spaces of modernity.

The flâneur/artist starts his journey in the auditorium where young women of the most fashionable society sit in snowy white in their boxes at the theatre. Next he watches elegant families strolling at leisure in the walks of a public garden, wives leaning complacently on the arms of husbands while skinny little girls play at making social class calls in mimicry of their elders. Then he moves on to the lowlier theatrical world where frail and slender dancers appear in a blaze of limelight admired by fat bourgeois men. At the café door, we meet a swell while indoors is his mistress, called in the text 'a fat baggage', who lacks practically nothing to make her a great lady except that practically nothing is practically everything for it is distinction (class). Then we enter the doors of Valentino's, the Prado or Casino, where against a background of hellish light, we encounter the protean image of wanton beauty, the courtesan, 'the perfect image of savagery that lurks in the heart of civilization'. Finally by degrees of destitution, he charts women, from the patrician airs of young and successful prostitutes to the poor slaves of the filthy stews....

/p. 73: Baudelaire's essay maps a sexualized representation of Paris as the city of women. It constructs a sexualized journey which can be correlated with impressionist practice. Clark has offered one map of impressionist painting following the trajectories of leisure from city centre by suburban railway to the suburbs. I want to propose another dimension of that map which links impressionist practice to the erotic territories of modernity. I have drawn up a grid using Baudelaire's categories and mapped the works of Manet, Degas and others on to this schema.

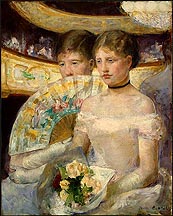

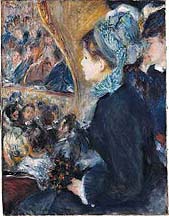

| Ladies | Theatre (Loge) | debutantes; young women of fashionable society | Renoir | Cassatt |

| Park | matrons, mothers, children, elegant families | Manet | Cassatt, Morisot | |

| XXXXXXXXXX | XXXXXXXX | XXXXXXXXXXXX | XXXXXXXXXX | XXXXXXXXXX |

| Fallen Women | Theatre (Backstage) | Dancers | Degas | |

| Cafes | mistresses and kept women | Manet, Renoir, Degas | ||

| Folies | THE COURTESAN 'protean image of wanton beauty' | Manet, Degas, Guys | ||

| Brothels | 'poor slaves of silthy stews' | Manet, Guys |

/p. 74: From the loge pieces by Renoir (admittedly not women of the highest society) to the Musique au Tuileries of Manet, Monet's park scenes and others easily cover this terrain where bourgeois men and women take their leisure. But then when we move backstage at the theatre we enter different worlds, still of men and women but differently placed by class. Degas's pictures of the dancers on stage and rehearsing are well known. Perhaps less familiar are his scenes illustrating the backstage Opér where members of the Jockey Club bargain for their evening's entertainment with the little performers. Both Degas and Manet represented the women who haunted cafés and as Theresa Ann Gronberg has shown these were working-class women often suspected of touting for custom as clandestine prostitutes.

Thence we can find examples sited in the Folies and cafés-concerts as well as the boudoirs of the courtesan. Even if Olympia cannot be situated/ p. 75: in a recognizable locality, reference was made in the reviews to the café Paul Niquet's, the haunt of the women who serviced the porters of Les Halles and a sign for the reviewer of total degradation and depravity.

/p. 75: Women and the Public Modern

Interior of the Paris Opera (Opera Garnier). Great hall used for intermissions and receptions.

Interior of the Opera Garnier

|

|

[Mary Cassatt's] Lydia at the theatre, 1879 and The Loge, 1882 situate us in the theatre with the young and fashionable but there could hardly be a greater difference between these paintings and the work of Renoir on this theme, The first outing, 1876, for example.

|

|

The stiff and formal poses the two young women in the painting by Cassatt were precisely calculated as the drawings for the work reveal. Their erect posture, one carefully grasping an unwrapped bouquet, the other sheltering behind a large fan, create a telling effect of suppressed excitement and extreme constraint, of unease in this public place, exposed and dressed up, on display. They are set at an oblique angle to the frame so that they are not contained by its edges, not framed and made a pretty picture for us as in The Loge by Renoir where the spectacle at which the scene is set and the spectacle the woman herself is made to offer, merge for the unacknowledged but presumed masculine spectator. In Renoir's The first outing the choice of a profile opens out the spectator's gaze into the auditorium and invites her/him to imagine that she/he is sharing in the main figure's excitement while she seems totally unaware of offering such a delightful spectacle. The lack of self-consciousness is, of course, purely contrived so that the viewer can enjoy the sight of the young girl.

|

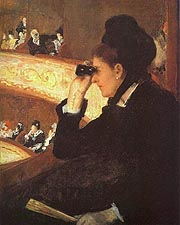

The mark of difference between the paintings by Renoir and Cassatt is the refusal in the latter of that complicity in the way the female protagonist is depicted. In a later painting, At the Opera, 1879, a woman is represented dressed in daytime or mourning black in a box at the theatre. She looks from the spectator into the distance in a direction which cuts across the plane of the picture but as the viewer follows her gaze another look is revealed steadfastly fixed on the woman in the foreground. The picture thus juxtaposes two looks, giving priority to that of the woman who is, remarkably, pictured actively looking. She does not return the viewer's gaze, a convention which confirms the viewer's right to look and appraise. Instead we find that the viewer outside the picture is evoked by being as it were the mirror image of the man looking in the picture.

This is, in a sense, the subject of the painting --the problematic of /p. 76: women out in public being vulnerable to a compromising gaze. The witty pun on the spectator outside the painting being matched by that within should not disguise the serious meaning of the fact that social spaces are policed by men's watching women and the positioning of the spectator outside the painting in relation to the man within it serves to indicate that the spectator participates in that game as well. The fact that the woman is pictured so actively looking, signified above all by the fact that her eyes are masked by opera glasses, prevents her being objectified and she figures as the subject of her own look.

Cassatt and Morisot painted pictures of women in public spaces but these all lie above a certain line on the grid I devised from Baudelaire's text. The other world of women was inaccessible to them while it was freely available to the men of the group and constantly entering /p. 78: representation as the very territory of their engagement with modernity. There is evidence that bourgeois women did no to the cafés-concerts but this is reported as a fact to regret and a symptom of modern decline....

To enter such spaces as the masked ball or the café-concert constituted a serious threat to a bourgeois woman's reputation and therefore her femininity. The guarded respectability of the lady could be soiled by mere visual contact for seeing was bound up with knowing. This other world of encounter between bourgeois men and women of another class was a no-go area for bourgeois women. It is the place where female sexuality or rather female bodies are bought and sold, where woman becomes both an exchangeable commodity and a seller of flesh, entering the economic domain through her direct exchanges with men. Here the division of the public and private mapped as a separation of the masculine and feminine is ruptured by money, the ruler of the public domain, and precisely what is banished from the home.

Femininity in its class-specific forms is maintained by the polarity virgin/whore which is mystifying representation of the economic exchanges in the patriarchal kinship system. In bourgeois ideologies of femininity the fact of the money and property relations which legally and economically constitute bourgeois marriage is conjured out of sight by the mystification of a one-off purchase of the rights to a body and its products as an effect of love to be sustained by duty and devotion.

Femininity should be understood therefore not as a condition of women but as the ideological form of the regulation of female sexuality within a familial, heterosexual domesticity which is ultimately organized by law. The spaces of femininity --ideologically, pictorially-- hardly articulate female sexualities. This is not to accept nineteenth-century notions of women's asexuality but to stress the difference between what was actually lived or how it was experienced and what was officially spoken or represented as female sexuality.

In the ideological and social spaces of femininity, female sexuality could not be directly registered. This has a crucial effect with regard to the use of artists who were women could make of the positionality represented by the gaze of the flâneur-- and therefore with regard to /p. 79 modernity. The gaze of the flâneur articulates and produces a masculine sexuality which in the modern sexual economy enjoys the freedom to look, appraise and possess, is deed or in fantasy....

It is not the public realm simply equated with the masculine which defines the flâneur/artist but access to a sexual realm which is marked by those interstitial spaces, the spaces of ambiguity, defined as such not only by the relatively unfixed or fantasizable class boundaries Clark makes so much of but because of cross-class sexual exchange. Women could enter and represent selected locations in the public sphere-- those of entertainment and display. But a line demarcates not the end of the public/private divide but the frontier of the spaces of femininity. Below this line lies the realm of the sexualized and commodified bodies of women, where nature is ended, where class, capital and masculine power invade and interlock. It is a line that marks off a class boundary but it reveals where new class formations of the bourgeois world restructured gender relations not only between men and women but between women of different classes.

/p.89: I hope it will now be clear that the significance of this argument extends beyond issues about impressionist painting and parity for artists who are women. Modernity is still with us, ever more acutely as our cities become in the exacerbated world of postmodernity, more and more a place of strangers and spectacle, while women are ever more vulnerable to violent assault while out in public and are denied the right to move around our cities safely. The spaces of femininity still regulate women's lives --from running the gauntlet of intrusive looks by men on the streets to surviving deadly sexual assaults. In rape trials, women on the street are assumed to be 'asking for it'. The configuration which shaped the work of Cassatt and Morisot still defines our world. It is relevant then to develop feminist analyses of the founding moments of /p. 90: modernity and modernism, to discern its sexualized structures, to discover past resistances and differences, to examine how women producers developed alternative models for negotiating modernity and the spaces of femininity.