Christianity as we have discussed it to date in this course has been associated with the urban context of the Greco-Roman world. With missionaries like St. Patrick we find something different. His mission (c. 432) to Ireland to spread the Gospel was to all people. He can be claimed to be the first to see it as his moral duty to go outside the empire to convert the heathen. No one had tried to introduce a religion organized around towns and dependent on the proclamation of the Word of God, in its original Greek or Latin translation, into a tribal society which had no towns and which knew neither Greek nor Latin. In fact literacy was introduced to them through the foreign languages of Greek and Latin, the languages of the Word of God.

Lacking an urban context, the missionaries needed a different institutional framework than in the Roman world. This different framework was monasticism. Monasticism had developed in the Roman world, but there it served as a form of retreat from the world. The Church itself was run by a secular clergy independent from the monasteries. In Ireland and in the rest of the Barbarian north, monasteries were the central institution: bases for missionary activity, centers for basic education in Latin, for book production, for the training of clergy, and for cultural and economic life.

The Irish Christianity of Patrick was spread to Scotland and northern England by missionaries like St. Columba, who founded off the west coast of Scotland the monastery of Iona in 565. This monastery became the mother house of Columban monasteries in Scotland and England.

Meanwhile under the sponsorship of Pope Gregory the Great (c. 540-604), missionaries were sent to southern England to spread Roman Christianity. St. Augustine arrived in England in 597 and established himself in Canterbury, which would become the traditional home of Christianity in England. St. Augustine and his successors sent missionaries to the north of England, principally to Northumbria, to convert the Angles and Saxons. This led to the dispute between the two forms of Christianity: the Irish tradition from Patrick and the Roman tradition from St. Augustine. These were resolved in the favor of Rome at the Council of Whitby in 664. In northern monasteries like Lindisfarne in southwestern Scotland, there was a complex mixture of Irish and Roman traditions.

A critical issue with the spread of Christianity was how the missionaries would respond to the indigenous traditions it encountered in the north. Would they supplant the local traditions or integrate them into the Christian tradition. The following excerpt from Bede's History of the English Church and People records a letter sent by Pope Gregory the Great to Abbot Mellitus on his departure for Britain in 601:

" To our well loved son Abbot

Mellitus: Gregory, servant of the servants of God.

"Since the departure of those of our fellowship who are bearing you company,

we have been seriously anxious, because we have received no news of your journey.

Therefore, when by God's help you reach our most reverend brother, Bishop Augustine,

we wish you to inform him that we have been giving careful thought to the affairs

of the English, and have come to the conclusion that the temples of the idols

among that people should on no account be destroyed. The idols are to be destroyed,

but the temples themselves are to be aspersed with holy water, altars set up

in them, and relics deposited there. For if these temples are well-built, they

must be purified from the worship of demons and dedicated to the service of

the true God. In this way, we hope that the people, seeing that their temples

are not destroyed, may abandon their error and, flocking more readily to their

accustomed resorts, may come to know and adore the true God. And since they

have a custom of sacrificing many oxen to demons, let some other solemnity be

substituted in its place, such as a day of Dedication or the Festivals of the

holy martyrs whose relics are enshrined there. On such occasions they might

well construct shelters of boughs for themselves around the churches that were

once temples, and celebrate the solemnity with devout feasting. They are no

longer to sacrifice beasts to the Devil, but they may kill them for food to

the praise of God, and give thanks to the Giver of all gifts for the plenty

they enjoy. If the people are allowed some worldly pleasures in this way, they

will more readily come to desire the joys of the spirit. For it is certainly

impossible to eradicate all errors from obstinate minds at one stroke, and whoever

wished to climb to a mountain top climbs gradually step by step, and not in

one leap. It was in this way that the Lord revealed Himself to the Israelite

people in Egypt, permitting the sacrifices formerly offered to the Devil to

be offered thenceforward to Himself instead....

This letter calls for the merging of traditions. This merger is well documented by the art of the period. The decoration of the so-called Ardagh Chalice (early eighth century) is clearly based on the same decorative vocabulary we saw used in the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial:

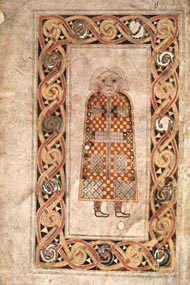

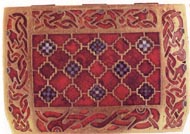

The first of the great Hiberno-Saxon Gospel books, the Book of Durrow clearly manifests the conversion of the metalwork tradition to the decoration of a manuscript:

|

|

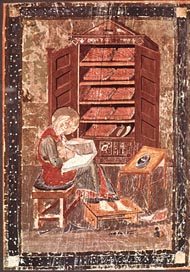

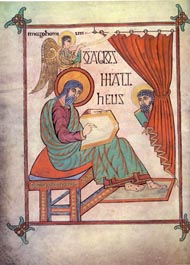

A famous and dramatic example of the different responses to the competing traditions is presented by a comparison of the author portrait of Ezra from the Codex Amiatinus early eighth century and the Evangelist portrait of St. Matthew from the Lindisfarne Gospels, late seventh or early eighth century:

|

|

The Codex Amiatinus was made in the Northumbrian monasteries of Wearmouth (dedicated to St. Peter and founded in 674 by Benedict Biscop) and Jarrow (dedicated to St. Paul and founded in 681 by an Anglo-Saxon Ceolfrith). The Codex Amiatinus was made at the command of Ceolfrith. He intended to present the manuscript as a gift to the pope, but he died in France in 716 on the way to Rome. This gift was intended as a testament to the dedication of Wearmouth and Jarrow to the Church of Rome.

Bookcase |

The unusual prominence given in this manuscript to Ezra can be perhaps be explained by the parallels between the story of Ezra and those of Benedict Biscop and his followers at Wearmouth and Jarrow. The story of Ezra marks the end of the Babylon Captivity of the Israelites and their return to Jerusalem and Juda. Ezra is repeatedly referred to as " priest, scribe instructed in the words and commandments of the Lord, and his ceremonies in Israel [1Esdras, 7, 11]." As "the most learned scribe of the law of the God of heaven [1Esdras, 7, 12]", Ezra was an appropriate model for Benedict Biscop and his followers at Wearmouth and Jarrow who had dedicated their lives to spreading the Word of God. One of the most important functions of these monasteries was the copying and dissemination of texts. The account of Ezra reading the law before the people has a striking parallel to the activities of the monks of Wearmouth and Jarrow and the power of the book:

| And all the people were gathered together as one man to the street which is before the water gate, and they spoke to Esdras the scribe, to bring the book of the law of Moses, which the Lord had commanded to Israel. 2 Then Esdras the priest brought the law before the multitude of men and women, and all those that could understand, the first day of the seventh month. 3 And he read it plainly in the street that was before the water gate, from the morning until midday, before the men, and the women, and all those that could understand: and the ears of all the people were attentive to the book....5 And Esdras opened the book before all the people: for he was above all the people: for he was above all the people: and when he had opened it, all the people stood. 6 And Esdras blessed the Lord the great God: and all the people answered, Amen, amen: lifting up their hands: and they bowed down, and adored God with their faces to the ground [2Esdras, 8, 1-6]." |

It is well known that the Ezra portrait is ultimately based on an Italian manuscript from the sixth century. The nine part division of the Bible indicated by the books in the cupboard corresponds to the so-called Codex Grandior, an edition of the Bible produced by Cassiodorus. Benedict Biscop and Ceolfrith in the establishment of Wearmouth and Jarrow as centers of education were emulating the model presented by Cassiodorus at his monastery of Vivarium. Benedict Biscop had visited Rome at least six times, and when he returned he brought back with him manuscripts, treasures, and relics. The acquisition of the Roman relics further established the link to the authority of the Roman Church.

| Then the most reverend Abbot Benedict prepared to go to Rome for the purpose of bringing home a supply of sacred books, some dear memorial of the remains of the blessed martyrs, a painting of the Bible story that would be worthy of veneration, and other gifts such as he was accustomed to bring back from his travels through many lands. But most of all he wanted instructors in the liturgical usage of the Roman rite who could teach the proper methods of chanting and of conducting services in the church he had just founded [The Life of Ceolfrith, Chapter IX as translated in Clinton Albertson, Anglo-Saxon Saints and Heroes, Fordham University Press, p. 252]. |

Every attention was made by Benedict Biscop and Ceolfrith to make the monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow "hot house" versions of Italian monasteries dedicated to the authority of Rome. The use of relics of Roman saints was an important way missionaries established the allegiance of newly founded churches and monasteries to the authority of Rome. The establishment of a uniformity in religious practice in observing the Roman rite was also a critical way of unifying the church under Rome. This was especially critical in the disputes with the competing Irish Christianity.

Standardization of a canonical form of the Bible was another challenge for the Church in establishing uniformity. Ceolfrith clearly was aware of this concern. The Life of Ceolfrith specifically refers to the production of three great Bibles:

| He enriched the monasteries most lavishly with the vessels used for the service of the church and the altar. He made princely additions to the library which he and Benedict had brought from Rome; among other things he had copies made of three Bibles, and then placed two of these in the churches of his two monasteries [Wearmouth and Jarrow], so that it would be easy for any one who wished to read any chapter of either Testament to find what he wanted. As for the third copy [the Codex Amiatinus]--being about to set out for Rome, he decided to offer it as a gift to the blessed Peter, Prince of the Apostles [Life of Ceolfrith, chapter XX, Albertson, p. 259]. |

Fragments of one of the other Ceolfrith Bibles were discovered being used as wrappers for estate papers. The so-called Greenwell Leaf (London, British Library, Additional MD 3777, verso) contains part of the text of the Third Book of Kings:

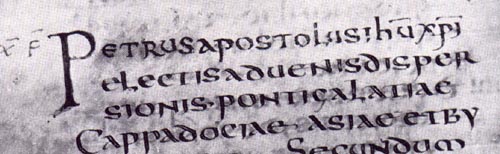

The layout and scripts of these Ceolfrith manuscripts clearly emulate Mediterranean models like the Codex Grandior. The script can be identified as the uncial script typical of Christian manuscripts from the fourth century onwards. The following sample comes from a sixth century New Testament manuscript perhaps written at Capua about 546:

The Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, Cotton MS Nero D.iv) was produced at the island monastery of Lindisfarne off the east coast of Scotland. A tenth century priest named Aldred added a colophon to the manuscript documenting its production:

| Eadfrith, Bishop of the Lindisfarne Church, originally wrote this book, for God and for Saint Cuthbert and --jointly-- for all the saints whose relics are in the Island. And Ethelwald, Bishop of the Lindisfarne islanders, impressed it on the outside and covered it --as he well knew how to do. And Billfrith, the anchorite, forged the ornaments which are on it on the outside and adorned it with gold and with gems and also with gilded-over silver --pure metal. And Aldred, unworthy and most miserable priest, glossed it in English between the lines with the help of God and Saint Cuthbert. |

Nothing is known of Eadfrith before he became in May 698 bishop of Lindisfarne, a position he held until his death in 721. Before becoming bishop, Eadfrith was presumably a member of the community of Lindisfarne. Paleographic examination suggests that the bulk of the manuscript was written in a single campaign by one scribe. Scholars generally accept a literal reading of Aldred's colophon, and assume that Eadfrith was this scribe. This leads to the assumption that the manuscript was written before 698 when Eadfrith became bishop since it is unlikely that he would have had the time to dedicate to this project after that date.

While the Codex Amiatinus reflects the clear emulation of Mediterranean models, the Lindisfarne Gospels represents a creative synthesis of the Roman tradition of the Codex Amiatinus and the local Irish tradition. Founded by monks from the Irish monastery of Iona about 635, Lindisfarne was in a position between the Irish and Roman traditions. A comparison of a text page from the Lindisfarne Gospels to the Greenwell Leaf shows significant similarities:

Instead of using the uncial script like the Ceofrith manuscripts in emulation of Mediterranean models, Eadfrith in the Lindisfarne Gospels uses the Irish Majuscule script. The most striking example of the synthesis of traditions evident in the Lindisfarne Gospels is evident in a comparison of the Evangelist portrait of St. Matthew and the Ezra portrait from the Codex Amiatinus. Whether directly or not, it is evident that both are ultimately based on a common visual model:

Compare the styles of these two works.

Tara Brooch, 8th century