Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 213 Assignments

Medici Patronage:

Magnificence and Splendor

Excerpt describing Cosimo de' Medici from Gene Brucker, Renaissance Florence: p. 119: Cosimo de' Medici ...[was] the most prominent citizen that reached manhood in the early fifteenth century. Vespasiano da Bisticci's biography of Cosimo is laudatory and uncritical, but it is an honest evaluation of the man, /p. 120: and depicts him as he was seen by the majority of his fellow-citizens. No modern biographer has succeeded in penetrating the surface of Cosimo's personality, of exposing the man behind the public facade. We can use this facade, however, to measure some of the changes that had occurred in the life style of the patriciate.

Cosimo's authority derived from his great wealth and his leadership of a faction. Vespasiano da Bisticci described a conversation between Cosimo and a political rival, in which the former articulated his political philosophy: "Now it seems to me only just and honest that I should prefer the good name and honor of my house to you: that I should work for my own interest rather than for yours. So you and I will act like two big dogs who, when they meet, smell one another and then, because they both have teeth, go their ways. Wherefore now you can attend /p. 121: to your affairs and I to mine." He demonstrated a particular talent for working behind the scenes, achieving his goals by manipulating others. His instruments were the bonds of obligation by which he tied his supporters to himself. Vespasiano wrote: "He rewarded those who brought him back [from exile], lending to one a good sum of money, and making a gift to another to help marry his daughter or buy lands...." His political enemies were not killed but exiled; the refusal to shed blood was characteristic of this cautious politician who gained his objectives by less flamboyant methods. In one sense, his style represented the triumph of the mercantile mentality. He typified the rational and calculating entrepreneur, the shrewd, toughminded realist who had banished passion and emotion from politics.

The material dimensions of Cosimo's life also reflect significant innovations in the patrician mode of living. The construction of a massive palace on the Via Larga provided the arena for a more refined and luxurious style of existence, which set the pattern for the Florentine upper class. Although Cosimo deliberately affected the manner of an old-fashioned merchant with simple tastes, his living style signalled the abandonment of such traditional virtues as austerity, thrift, and frugality, and the acceptance of ostentation as a socially desirable trait. The new ethic received political sanction with the repeal or the nonenforcement of sumptuary legislation, a characteristic feature of communal policy in earlier times. Seven years after Cosimo's death, his grandson Lorenzo stated that the Medici had spent over 600,000 florins for public purposes since 1434, and he remarked that this expenditure "casts a brilliant light upon our condition in the city." The living standard in the Medici palace was more luxurious than Cosimo's ancestors had ever known. This expenditure for magnificent decor, costly furnishings, and elegant clothing was designed to provide an impressive setting for prominent guests, to create an image of Medici (and Florentine) wealth and taste. Cosimo was host to both the German emperor Frederick III and the Byzantine emperor John Paleologue, as well as other, less distinguished princes of church and state who dined and lodged in the palace on the Via Larga, or in the villas at Careggi and Cafaffiuolo. The Medici were not the only /p. 122: Florentine family to dispense lavish hospitality, but the scale and opulence of their entertainments marked them as the city's most illustrious house. A visit to the Medici household was a dazzling experience, as young Galeazzo Maria Sforza, son of the lord of Milan, testified in letters to his father Francesco. This product of a courtly milieu extolled the beauties and charms of the villa at Careggi, and praised the musical and dramatic entertainments which were provided for his amusement.

The trend toward ostentation and luxury which is so apparent in the private lives of the Medici was also visible in their public ceremonies. Both funerals and weddings had become more formal, more elaborate, and more expensive. The temptation to use these occasions to publicize family wealth and status was strong, but in the past, it had been restrained by sumptuary laws and by characteristic Florentine aversion to wasteful expenditure. In the Quattrocento, these restraints were no longer effective. Chronicles of the Medici family describe the elaborate character of these events, and also their cost....

p. 123: There is no simple explanation for this intensified patrician impulse to express itself in such material terms as spending inflated sums on dowries and indulging in conspicuous consumption./p. 124: It cannot be understood solely in terms of greater prosperity; Medicean Florence was not richer than the Florence of Giotto or Boccaccio. Nor should this phenomenon be seen as a total rejection of traditional values. The penchant for luxury had always existed in patrician society, most strongly among the old magnate clans, but it had been restrained by ascetic impulses some of which were religious, and some mercantile in origin. This tenuous balance was destroyed in the fifteenth century. By indulging in extravagance and display, patricians were announcing their release from the restraints imposed by egalitarianism: they were emphasizing their special, exalted place in Florentine society.

Cosimo's career reflects this aristocratic, elitist tendency. His pose as a simple merchant, his pretense of being no greater than any other citizen, deluded no one. He crushed his enemies and exalted his friends and supporters. The artisan or shopkeeper who encountered Cosimo in the street might take pleasure from rubbing shoulders with the great man, but he also knew that the banker could determine his fate. Cosimo's father, Giovanni, had been at home in the streets, the squares, and the churches of the city; he had conducted his business in his shop in the Old Market. Cosimo erected a vast palace which symbolized both his power and his separation from his fellow-citizens. There in his private chapel, decorated by Gozzoli with magnificent frescoes, he worshipped in isolation. There in his study he made the major decisions which determined the course of Florentine policy. Before his death, Cosimo had created the structure for that esoteric milieu in which his grandson Lorenzo was to flourish.

|

Excerpt from John T. Paoletti and Gary M. Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy:

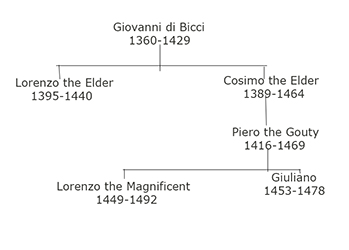

p. 220: The Medici: The rise to power of the Medici in Florence began in 1418 when Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici (c. 1360-1429) became the banker to the papacy and established the wealth of the family on a sure footing. Giovanni's son, Cosimo (1389-1464), steadily increased the control of his family /p. 221: over the political fortunes of Florence after his return from exile in 1434, leading eventually to their de facto rulership of the city until they were ousted in a revolt in 1494.

Cosimo and his heirs worked carefully to maintain control of the government through an elaborate political network supported by their wealth. They also sought to dismantle or dominate power bases in the city that were threats to their control. Ultimately the Medici brought the city under their influence, without, however, disturbing the appearances of the formal structures of government which had been in place for two centuries. In name Florence remained a republic, while in practice the Medici functioned rather like princes in their rule over it. The Medici surrounded themselves with visual images denoting rulership, although they steadfastly maintained that they were ordinary citizens within the republic. The differences between appearance and reality could not help but affect the art produced within the city.

|

Excerpt from Richard Goldthwaite, Wealth and the Demand for Art in Italy 1300-1600: p.122: [A] prodigious proliferation of private altars and chapels began that continued across the entire period we are examining. The rich were the first to move in, but by the fifteenth century ordinary people were also looking for space. The Florentine chapter in this history is well documented. The earliest chapels there appear around the transepts (and therefore near the high altar) of the great mendicant churches, such as those built by the Bardi, Peruzzi, and other families at Santa Croce. The richest men, or the ones who could drive the hardest bargain (like the Alberti, again at Santa Croce), took over the patronage of the high altar itself [see the Tournabouni Chapel at Santa Maria Novella], whence the space could extend into the nave to incorporate the entire choir area. Others moved into equally prestigious areas such as the sacristy (the Medici at San Lorenzo [and the Strozzi at Santa Trinita]) or the chapter room (the Pazzi Chapel at Santa Croce). Once these zones had been appropriated, large chapel spaces could be built on as additions to the nave...; and when an artist like Brunelleschi /p. 123: got such a commission...the chapel became a prominent architectural monument itself. The ultimate step was to build a completely new church planned from the beginning to maximize the space for private chapels --and to pay for it by selling off chapels pro rata. Thus the demand for chapels became a catalyst for rebuilding in the fifteenth century. Brunelleschi took this demand so much for granted that he made all of his churches chapel-lined --eight around the rotunda of Santa Maria degli Angeli, sixteen down the two sides of the nave of San Lorenzo, thirty-eight around the entire circumference of Santo Spirito except for the façade.... It has been estimated that there were six hundred chapels scattered throughout Florentine churches in the fifteenth century.... |

|

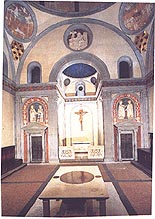

Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo (Medici Chapel) Designed by Brunelleschi |

Sacristy of Sta. Trinitá (Strozzi Chapel) |

THE

OLD SACRISTY: The beginnings of Medici artistic patronage in fifteenth-century

Florence were hardly modest. Giovanni di Bicci, along with other families

in his neighborhood, undertook the reconstruction of the church of San Lorenzo.

![]() Cosimo

acted as one of four operai for the commission of Ghiberti's St.

Matthew for the Arte del Cambio at Or San Michele; a forced assessment

of guild members in 1420 indicates that Medici contributions were significantly

more generous than those of the Strozzi, the wealthiest family of the oligarchic

faction. Even in a commission contracted by a guild, family and personal rivalries

played important roles.

Cosimo

acted as one of four operai for the commission of Ghiberti's St.

Matthew for the Arte del Cambio at Or San Michele; a forced assessment

of guild members in 1420 indicates that Medici contributions were significantly

more generous than those of the Strozzi, the wealthiest family of the oligarchic

faction. Even in a commission contracted by a guild, family and personal rivalries

played important roles.

/p. 187: Sometime around 1418 a group of citizens living in the neighborhood of the church of San Lorenzo decided to act together to rebuild their parish church. Led by Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, then the banker to the papacy and head of a family attempting to establish its prominence in the city, each member of the group agreed to contribute funds for the construction of his family's chapel around the transept of the proposed new structure. Giovanni agreed to build the sacristy of the new building as a family burial site and also to build an adjacent double chapel at the end of /p. 188: the transept. This gave the Medici patronage rights over a traditionally important part of the building --the sacristy-- and also more than twice as much space as any other family participating in the project.

The building already at the site was an eleventh-century Romanesque church, itself a replacement for an Early Christian basilica dedicated in 393 by no less a person than St. Ambrose, who had also consecrated Florence's first bishop. San Lorenzo, then, represented the entire history of Florence --more so, even, than the Duomo, which had a later foundation....

/p. 221: Although the Old Sacristy was substantially complete at the time of Giovanni's death in 1429, it owes most if its subsequent decoration to Cosimo and his brother Lorenzo (not to be confused wtih Lorenzo the Magnificent, Cosimo's grandson).... The classically inspired sarcophagus of Giovanni de' Medici and his wife Piccarda, lies directly below the lantern, emphasizing the patrons' hopes for eternal life. The inscription on it names both Cosimo and his brother Lorenzo as its commissioners..., jointly discharging their filial responsibilities. In a social system in which the oldest son became the head of the family upon the death of the father, this manifestation of equality speaks quietly but eloquently about the unity of the Medici family and deflects attention for Cosimo's leadership role just at the time when he was also beginning his consolidation of political power in the city.

The brothers' presence in the sacristy is also marked by other visual signs. Large stucco reliefs over small doors on either side of the altar wall present dramatically posed standing figures of saints Lawrence and Stephen on the left and saints Cosmas and Damian on the right. These figures could simply be titular saints --Lawrence (Lorenzo), for the church in which they appear and Cosmas and Damian, the doctors (medici), for the family that had built the Old Sacristy. These saints, however, are also the patron saints of Lorenzo and Cosimo, who probably commissioned these reliefs after their father's death, the sons appearing in the guise of their patron saints just as Giovanni does in the roundel of St. John the Evangelist above the altar arch....

/p. 222: SAN LORENZO: Work that had begun so earnestly on the transept of San Lorenzo had all but ceased by the time of Giovanni di Bicci's death in 1429. It was not until 1442 that Cosimo declared that he would himself pay for the construction of the new building. In doing so he assumed property rights over the main altar area and he stipulated that no family crest other than that of the Medici appear in the church. Cosimo's assumption /p. 223: of the building costs effectively transformed San Lorenzo into a Medici structure, despite the presence of families who maintained control of the chapels along the transept. Insofar as the building marks the site of the first Christian church in Florence, dedicated in 393, Cosimo also symbolically appropriated the entire religious history of the city for his family; the princely overtones of this act recall royal foundations such as St. Denis, outside Paris, or the Visconti patronage of the Certosa of Pavia. In a city that called itself a republic, this form of patronage must have seemed extraordinary.

SAN MARCO: Cosimo's activities at San Lorenzo were not his only endeavors at church building. When the Dominican order took charge of the dilapidated monastery of San Marco in 1436, Cosimo hired Michelozzo di Bartolommeo (1396-1472) to rebuild it. Cosimo also added a library (which he then helped to fill with books), a cloister, a chapter room, a bronze bell, and church furnishings, including an imposing altarpiece by Fra Angelico (c. 1395-1455), for the main altar.

The San Marco Altarpiece was badly abraded through faulty restoration in the nineteenth century, yet it is still remarkable for what it says of Fra Angelico's work, and of his patron's wishes. In some sense the image is profoundly traditional, with a centrally placed group of the Virgin and Child flanked by angels and saints. Yet the setting has an arrestingly open, spacious quality. The architectural throne, with its shell niche framing the Virgin and Child, is large and decorated with classical garlands and Corinthian pilasters. Space expands not only into the distance, but also behind and around the figures and focuses on the hand of the Virgin, tellingly placed in front of her womb, as if to emphasize the Incarnation of Christ and her maternity, a central concern in Dominican theology. The inscription from the Dominican Little Office on the hem of the Virgin's garment emphasizes this tenet: "...like a vine I caused loveliness to bud, and my blossoms became glorious and abundant fruit." The background landscape, framed by patterned draperies, is remarkably naturalistic in its depiction of trees, of the sea meeting the land, and of the sunlit sky. It too relates to a holy text; in the Old Testament book of Ecclesiasticus, Wisdom says, "I have grown tall as a cedar on Lebanon, as a cypress on Mount Hermon; I have grown tall as a palm in Engedi, as the rose bushes of Jericho; as a fine olive in the plain, as a plane tree I have grown tall" (24:13-15). The illusionistic draperies, tied to the frame at the upper left and right, refer to contemporary altarpieces, which were actually covered by cloth, drawn open only on festival days. Here, by contrast, the mood would always be jubilant, a stage set for the adoration of the Child whose redemption of the world is symbolized by the crucifix on the small tabernacle door that interrupts the composition at the bottom.

The draperies of the kneeling figures, with their thick folds and weightiness, suggest that Fra Angelico, for all the tranquility of his images, had looked carefully at the more /p. 224: dramatic painting of Masaccio. Such features as the hanging cloth behind the figures and the expressive modeling of the faces also suggest that he had studied the work of Gentile da Fabriano....

Although

there are obvious differences in spatial organization and figural structure

between Fra Angelico's San Marco Altarpiece and  Gentile's

Adoration of the Magi painted for Palla Strozzi, the Medici altarpiece

has a sense of opulence no less finely calibrated than the Strozzi. Rich gold

embellished draperies hang not only at the left and right of the composition

but behind the Virgin and Child as well. Gold is used generously in the haloes

of the figures, as it was originally in the borders and surfaces of many of

the robes worn by them. The luxuriousness of the arboreal landscape is matched

by the richness of the patterning on the cloth separating it from the figures

and of that on the carpet.

Gentile's

Adoration of the Magi painted for Palla Strozzi, the Medici altarpiece

has a sense of opulence no less finely calibrated than the Strozzi. Rich gold

embellished draperies hang not only at the left and right of the composition

but behind the Virgin and Child as well. Gold is used generously in the haloes

of the figures, as it was originally in the borders and surfaces of many of

the robes worn by them. The luxuriousness of the arboreal landscape is matched

by the richness of the patterning on the cloth separating it from the figures

and of that on the carpet.

/p.225: It is worth noting, however, that instead of choosing the courtly subject matter of the Magi, Cosimo ordered a traditional sacra conversazione for his altarpiece. The sobriety of the figures is appropriate for their Dominican location, yet their poses give them the gravity of Roman statemen, unlike the lively, elegant figures in the Strozzi Altarpiece. Cosimo and Fra Angelico seem deliberately to have employed a visual language that could be seen as an alternative to that used by the leading member of the oligarchy --and yet at the same time to have incorporated some of the signs of wealth and social prestige that characterize the Strozzi commission.

As in the decoration for the Old Sacristy there is a dynastic "subtext" in the imagery in the San Marco Altarpiece. Its patron, Cosimo de' Medici, appears in the guise of St. Cosmas kneeling in the traditional position of the donor in the left foreground of the painting. John the Evangelist, standing second from the left, probably represents Giovanni di Bicci, Cosimo's father; and St. Lawrence, at the far left with his grill, Cosimo's brother, Lorenzo, who died in 1440, the year the painting was completed. The red balls on a gold ground of the Medici family crest appear along the border of the rug at the bottom of the altarpiece. The red and white floral garlands hanging at the top of the painting, although most likely referring to Ecclesiasticus, represent the heraldic colors of the city of Florence, uniting Medici and civic imagery once again.

|

The northern Italian artist Domenico Veneziano became aware of the Medici commission for the San Marco Altarpiece. In hopes of gaining the commission, Domenico wrote the following letter to Piero di Cosimo de'Medici to intercede on his behalf to Piero's father, Cosimo de' Medici: To the honorable and generous man Piero di Cosimo de' Medici of Florence, his honored superior, in Ferrara. Honorable and generous Sir. After the due salutations. I inform you that by God's grace I am well, and I wish to see you well and happy. Many many times I have asked about you, and have never learned anything, except that I asked Manno Donati, who told me you were in Ferrara, and in excellent health. I was greatly relieved, and having first learned where you were, I would have written you for my comfort and duty. Considering my low condition does not deserve to write to your noblity, only the perfect and good love I have for you and all your people gives me the daring to write, considering how duty-bound I am to do so. Just now I have heard that Cosimo [de' Medici, Piero's father] has decided to have an altarpiece made, in other words painted, and wants a magnificent work, which pleases me very much. And it would please me more if through your generosity I could paint it. And if that happens, I am in hopes with God's help to do marvelous things, although there are good masters like Fra Filippo and Fra Giovanni [Angelico] who have much work to do. Fra Filippo in particular has a panel going to Santo Spirito which he won't finish in five years working day and night, it's so big. But however that may be, my great good will to serve you makes me presume to offer myself. And in case I should do less well than anyone at all, I wish to be obligated to any merited punishment, and to provide any test sample needed, doing honor to everyone. And if the work were so large that Cosimo decided to give it to several masters, or else more to one than to another, I beg you as far as a servant may beg a master that you may be pleased to enlist your strength favorably and helpfully to me in arranging that I have come some little part of it. For if you knew how I long to do some famous work, and specially for you, you would be favorable to me, I'm certain we won't be wanting in that. I beg you to do anything possible, and I promise you my work will bring you honor. Nothing else at the moment, except that I can do anything for you here, command me as your servant, and I hope you won't dislike giving me a reply, and above all inform me of your health, wnich I desire above all things, and Christ prosper you and fulfill all your duties. By your most faithful servant Domenico da Venezia painter, commending himself you you, in Perugia, 1438, first of April. |

Thus, just before taking control of the main altar of San Lorenzo in 1442, Cosimo also visually appropriated the high altar of San Marco, just a short distance away from his home, further enhancing his presence in the city. Medici patronage, also marked by the appearance of their crest on the exterior of the monastic buildings, served as a public reminder of the family's power as well as generosity.

| Excerpt from Richard Goldthwaite, Wealth and the Demand of Art in Italy 1300-1600, p. 216: Palaces were obviously family, not just individual, monuments. They were usually built in the neighborhood where the family had deep roots, and their builders probably viewed them as a symbol of family traditions and a focus for the loyalties of the wider family collectivity. They also looked to the future, for they were built to accomodate the dynasty that derived from the builder and to give it a prominent physical presence. |

THE MEDICI PALACE: When in 1446, Cosimo de' Medici began to build his palace on the Via Larga (now the Via Cavour), he had already hired and dismissed Brunelleschi as its architect and replaced him with Michelozzo, supposedly because Brunelleschi's model was for too grand a structure. Yet the palace that Cosimo built was more splendid than any in the city, leading to speculation that Brunelleschi's project placed the palace opposite the church of San Lorenzo rather than on its current site. Such a configuration of church and palace, given Cosimo's take-over of San Lorenzo, would have referenced to a well-known architectural iconography of authority most typically seen in juxtapositions of bishops' palaces and cathedrals, a message too blatant for Cosimo, who maintained that he was merely an ordinary citizen of the republic, despite his de facto control over the state.

The exterior

of the palace is striking in its use of extremely heavy rusticated masonry

on the ground story, which gives the building a fortress-like aspect --softened

in the increasingly refined treatment of surface on the stories above.  The

rustication of the lower story is typical of Florentine palazzi of the fourteenth

and early fifteenth centuries, a conservative element suggesting Cosimo's

adherence to tradition and his equality with other citizens who had built

similar, if smaller, palaces. Yet the extreme heaviness of the rustication

and the double lancet windows of the upper stories can be found

The

rustication of the lower story is typical of Florentine palazzi of the fourteenth

and early fifteenth centuries, a conservative element suggesting Cosimo's

adherence to tradition and his equality with other citizens who had built

similar, if smaller, palaces. Yet the extreme heaviness of the rustication

and the double lancet windows of the upper stories can be found  only

at the Palazzo dell Signoria, thus linking the Medici architecturally with

the city's main site of sovereignty. None of this vocabulary is classical

in form, except for the unrelieved rustication, which echoes that of the massive

wall around the back of the Forum of Augustus in Rome, thus lending further

suggestions of rulership to the Medici inhabitants.

only

at the Palazzo dell Signoria, thus linking the Medici architecturally with

the city's main site of sovereignty. None of this vocabulary is classical

in form, except for the unrelieved rustication, which echoes that of the massive

wall around the back of the Forum of Augustus in Rome, thus lending further

suggestions of rulership to the Medici inhabitants.

Deviating

from normal building practice in Florence, Cosimo built his palace from the

foundations up, having destroyed whatever pre-existing structures were on

the site. A more common practice was for owners to acquire adjacent properties,

which they then enveloped with a thin facing of stone; this presented a unified

façade to the street while the interior spaces maintained some of the

haphazard /p. 226: arrangement of the original buildings.  A

renovation and restructuring of family properties begun by Giovanni Rucellai

just shortly after work began on the Medici Palace demonstrates both the innovation

and the traditional aspects of the latter. The masonry blocks of the Palazzo

Rucellai form a veneer over the surfaces of a row of buildings; this façade

ends raggedly at the right in anticipation of the purchase of another property.

A

renovation and restructuring of family properties begun by Giovanni Rucellai

just shortly after work began on the Medici Palace demonstrates both the innovation

and the traditional aspects of the latter. The masonry blocks of the Palazzo

Rucellai form a veneer over the surfaces of a row of buildings; this façade

ends raggedly at the right in anticipation of the purchase of another property.

Each

story is separated into bays by pilasters, with a different order of capital

used at each level -- a hierarchy also used on the Colosseum in Rome. Thick

cornices decorated with classicizing ornament divide the stories. The uniformity

of the Rucellai façade also disguises the commercial function of the

ground floor implied by rustication by removing the differentiation of surface

treatment between the stories so carefully maintained in the Medici Palace.

Both palazzi, however, like their predecessors in Florence, present a block-like

solidity on the street that suggests the unity of the family living behind

the façade. Such families, of course, normally included at least two

generations of males, with their wives, children and servants.

Each

story is separated into bays by pilasters, with a different order of capital

used at each level -- a hierarchy also used on the Colosseum in Rome. Thick

cornices decorated with classicizing ornament divide the stories. The uniformity

of the Rucellai façade also disguises the commercial function of the

ground floor implied by rustication by removing the differentiation of surface

treatment between the stories so carefully maintained in the Medici Palace.

Both palazzi, however, like their predecessors in Florence, present a block-like

solidity on the street that suggests the unity of the family living behind

the façade. Such families, of course, normally included at least two

generations of males, with their wives, children and servants.

|

|

The central courtyard of the Medici Palace is strikingly different from the exterior of the building. Here the novelty of the building becomes obvious in the refined classical detailing of the arcade which surrounds the courtyard, and in the sculpted roundels suggesting ancient Roman gems that decorate the frieze above the arcade. Whether Cosimo and Michelozzo drew on local sources for this courtyard or on courtyards that they would have seen in northern Italy during Cosimo's exile in 1433-34, the size, the uniform order, and the allusions to classical forms were new to Florentine architecture.

PORTRAIT BUSTS

Although

Cosimo was the patron for the architecture of the Medici Palace, his son Piero

apparently took responsibility for the lavish decoration of its rooms. One

of Piero's earliest commissions marks his inventiveness. He employed Mino

da Fiesole (1429-84) to carve marble portrait busts of himself and his brother

Giovanni. Piero's portrait is a vivid portrayal of the actual features of

the man combined with a stoic vitality in his firmly set features and turning

head. It was fairly common practice at this time to make life masks or death

masks of important people from wax or plaster of Paris; but Piero's bust,

finished in 1453, marks the first example in marble to recall antique ![]() Roman

portraits, a model appropriate for a citizen of a republic. Somewhat earlier

medals of rulers, also modeled on Roman sources, may also have influenced

Piero's commission. The vertical borders of his clothing are carved with Piero's

personal crest of a diamond ring with a ribbon woven through it bearing the

/p. 227: word SEMPER (Latin for "always"). The message of Medici

permanence rings loud and clear to anyone who might have thought that Medici

power in republican Florence was a passing aberration.

Roman

portraits, a model appropriate for a citizen of a republic. Somewhat earlier

medals of rulers, also modeled on Roman sources, may also have influenced

Piero's commission. The vertical borders of his clothing are carved with Piero's

personal crest of a diamond ring with a ribbon woven through it bearing the

/p. 227: word SEMPER (Latin for "always"). The message of Medici

permanence rings loud and clear to anyone who might have thought that Medici

power in republican Florence was a passing aberration.

|

The Renaissance Medal Excerpt from Laurie Schneider Adams, Italian Renaissance Art, p. 145: A feature of the Classical revival in fifteenth-century Italy was the production of medals, usually made of bronze or lead. They were inspired by imperial Roman coins, which were smaller than the medals but similar in design --a bust-length profile of an emperor on the obverse, a emblem on the reverse, and an inscription.

During the Renaissance, medals were commissioned by various rulers and wealthy families as a way of circulating their images in portable, relatively inexpensive form. In addition, the message conveyed by the emblem or scene on the reverse could serve the function of political propaganda. To a certain extent, the iconography of a medal and its inscription provide biographical insights into the patron. Sometimes medals were struck to commemorate the design of a building in which case they can be useful architectural documents. |

||||

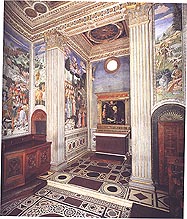

/ P. 227: DECORATION OF THE MEDICI PALACE

The small chapel of the Medici Palace is strikingly ornate. The elaborately coffered and gilded ceiling and the richly inlaid marble floor centered around a porphyry disk form a suitably grand setting for the spectacular frescoes on the walls. Beginning on the right wall of the chapel and moving clockwise around the room are frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli depicting the procession of the Magi to Bethlehem. With one king and his retinue occupying each wall, the procession directs the viewer to the altarpiece, which depicts the adoration of the Christ Child.

The wall

with the youngest king is particularly lavish in its treatment of costume,

recalling

the treatment of the same subject commissioned by Palla Strozzi. Piero seem

have appropriated both the subject matter and the style of the earlier painting,

as if to supplant the exiled Strozzi by assuming the very pictorial vocabulary

that had characterized his commission.

recalling

the treatment of the same subject commissioned by Palla Strozzi. Piero seem

have appropriated both the subject matter and the style of the earlier painting,

as if to supplant the exiled Strozzi by assuming the very pictorial vocabulary

that had characterized his commission.

The two mounted figures behind the young king are Piero de' Medici, on the white horse, and Piero's father, Cosimo, on the donkey. Although there is considerable dispute over the identity of the young king, he probably represents an idealized ten-year-old Lorenzo (1449-92), Piero's first son, who, in luxurious costume, had ridden the lead horse during an elaborate public ceremony staged by Piero in 1459 to honor Pope Pius II and Galeazzo Maria Sforza of Milan, both then visiting Florence. This role as one of the Magi would have been appropriate for Lorenzo, since he had been baptized on January 6, the feast of the Magi. Moreover the men of the Medici family belonged to the Company of the Magi, a confraternity that processed through the city each year on that feast day, from the monastery church of San Marco, where the relics of the Magi were kepts, past the Medici Palace, to the Baptistry. Thus this fresco in the private chapel of the Medici, where Piero often greeted visiting dignitaries, gave a noticeably royal /p. 228: cast to the family while at the same time celebrating their civic generosity and religious devotion.

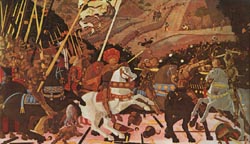

Other rooms in the palace conveyed equally complex messages. Inventories of the period indicate that a room marked as Lorenzo's was decorated with three large paintings by Paolo Uccello showing the battle of San Romano. The victorious general, Niccolò da Tolentino, appears in one of them with a banner carrying his device of a knot floating above his head. Uccello's paintings of this battle have a curiously frozen, doll-like quality. The geometrically simplified humans and animals and the carefully arranged angles of the fallen lances indicate the painter's reputed interest in the new science of perspective. Behind the figures at the left of the panel shown are trees bearing bright oranges, a fruit known during this time as mala medica, or "medicinal apple." Since the Medici name means "doctors", it was natural for them to choose this fruit as their symbol.

In addition to their charm these battle scenes are important because such subject matter was at that time depicted in the palaces of princes and on the walls of town halls to commemorate state military victories. Thus Lorenzo's room seems to have conflated not only citizen and prince but also private room and public council chamber, giving the family a visual language of rule.

An even more obvious appropriation of civic imagery can be seen in a small table bronze of Hercules and Anteus made for the Medici by Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1433-98). Hercules had been represented on the state seal of Florence since the end of the thirteenth century [Gregorio Dati in his Istoria du Firenze explains that the inclusion of Hercules on the seal of the Signoria is meant "to signify that Hercules, who was a giant, overcame all tyrants and evil lords as the Florentines have done." D. Kent, Cosimo de' Medici and the Florentine Renaissance, pp. 286-87]. Pollaiuolo's sculpture depicts the defeat of Anteus, achieved by lifting him off the ground, since Anteus derived his strength from his mother, Earth (Ge).... In medium as well as subject matter, such bronze statuettes mark an innovation in Florentine sculpture and the extension of a classical vocabulary into the domestic interior.

DONATELLO'S BRONZE DAVID AND JUDITH AND HOLOFERNES

| The following inscription was apparently associated with the statue: "The victor is whoever defends the fatherland. God crushes the wrath of an enormous foe. Behold! a boy overcame a great tyrant. Conquer, O citizens!" (D. Kent, Cosimo de' Medici and the Florentine Renaissance, p. 283) |

Donatello's bronze David is one of the best-known of the Medici commissions and yet one of the most perplexing. It is recorded in 1469 in a description of the wedding festivities of Piero's son, Lorenzo, and Clarice Orsini. The slightly smaller than life-sized statue then stood on a column in the courtyard of the Medici Palace, although the figure may well have been made for another site. The sleekly sensual depiction of the adolescent David , who stands in a languid pose, his left foot carelessly resting on Goliath's severed head, is remarkable for its naturalism. Donatello departed from tradition by presenting David nude, in the manner of a classical hero. Yet despite references to antique column statues and to the antique gems carved on Goliath's helmet, the treatment of the body does not recall the idealized male nudes of antiquity. This is a slim, pre-pubescent boy, not a powerful man. The unusual representation of the David suggests that Piero de' Medici wished to convey more than the usual meanings attached to this subject when he placed the statue in the Medici courtyard.

Piero and Donatello were, of course, aware that Donatello's earlier marble statue of David stood in the Palazzo della Signoria, placed in front of a wall which was painted blue and decorated with gold fleur-de-lys, one of the symbols of Florence. David had become a metaphor for the city, strong in protecting its freedoms from external threat. Piero's placement of the David in the private context of the palace thus appropriated civic imagery for the Medici. Contemporary awareness /p. 230: of this strategy of appropriation can be found in two later events. In 1476 Lorenzo and Giuliano de' Medici sold to the Signoria a traditionally clothed bronze David by Verocchio, then also in the Medici Palace, for placement in the Palazzo della Signoria, thus parting with the less problematic of the two Davids in their palace. In 1495, after the expulsion of the Medici from the city, the Signoria transported Donatello's David to the courtyard of the Palazzo della Signoria, a new inscription making explicit recognition of the state iconography carried by the statue....

The placement of the David in the Medici palace courtyard resonates with the marriage festivities of 1469. For the wedding feast the women were seated on the second floor of palace, looking down into the courtyard --just as Michal, David's wife, looked from her balcony at her husband. This then would have transformed the David into Lorenzo, a youthful hero growing into a wise ruler, just as the young king in the palace chapel frescoes evokes Lorenzo's role as a courtier in the 1459 civic procession honoring the Pope and Galeazzo Sforza. The multiple meanings evoked by the David typify the complex interweaving of personal and public imagery in Medici commissions.

Paired with the David in Medici imagery was Donatello's bronze statue of Judith and Holofernes. As a woman who saved the Jewish nation from foreign domination by slaying the Assyrian general Holofernes, Judith is obviously a counterpart of David. In that respect she is also a civic icon. Intended as a fountain sculpture in a small garden within the palace complex, that statue is an early example of sculpture meant to be seen in the round, with no single viewpoint fexed for the observer. Judith's heavy garments contrast with the near nakedness and overtly sensual fleshiness of Holoferne. Judith's foot /p. 232: is placed squarely on Holofernes's groin as her hand rises for the second time to strike at his already partially severed head. As part of the fountain, the statue would have had water trickling from the corners of the cushion on which the figures are placed --a startling addition of a gurgling sound to the already grizzly scene. The sculpture could be interpreted simply as virtue overcoming vice; however, a political meaning is clearly implied by the inscription that Piero originally placed on the group: "Piero, son of Cosimo, has dedicated the statue of this woman to that liberty and fortitude bestowed on the republic by the invincible and constant spirit of the citizens."

For a recent account of the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici see: Dale Kent, Cosimo de' Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron's Oeuvre, New Haven, Yale University, 2000.

Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 213 Assignments