Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 213 Assignments

Introductory Material

Florence as seen by an artist of the Quattrocento. Florentine wood engraving of c. 1480.

San Gimignano with clan towers.

Map of Italy

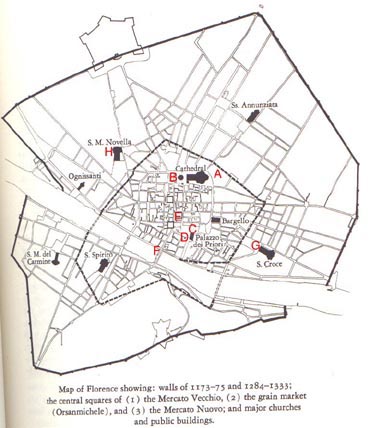

Map of Florence

|

A

|

Duomo (Cathedral), begun in 1296. The dome (1420-36) was designed by Brunelleschi,The Campanile or bell tower was begun by Giotto, 1334-43. | ||

|

B

|

Baptistry, c. 1059-1150. The Baptistry is the best preserved example of Romanesque architecture in Florence. See the page dedicated to the Baptistry Competition for a discussion of the significance of the Baptistry. For the Baptistry mosaics | ||

|

C

|

Palazzo dei Priori (now known as the Palazzo Vecchio). 1299-1310. Originally planned in 1285, just three years after the Priorate was established, the Palazzo dei Priori was built on land appropriated by the Guelph party after the defeat of their rivals the Ghibellines, or imperial party. This marks the dominance of the merchant class which was going to lead to Florence's economic prosperity based on its flourishing industries and international trade. | ||

|

D

|

Piazza della Signoria with the Uffizi on the left and the Loggia della Signoria (dei Lanzi) in the middle. The Loggia was constructed betwee 1376 and 1382. It has been noted that it is based on the Basilica of Constantine in Rome. It was believed that this major Roman building was a Temple of Peace. Notice the copy of Michelangelo's David in the left foreground adjacent to the primary entrance of the Palazzo dei Priori. | ||

|

E

|

Orsanmichele, grain exchange and shrine, was begun in 1284. It was built on land that had previously been an oratory to St. Michael. Niches on the exterior were assigned to the principal guilds to place in them statues of their patron saints. The focus of the interior was on an elaborate tabernacle which enshrined a miracle working image of the Virgin. | ||

|

F

|

Ponte Vecchio | ||

|

G

|

|

Santa Croce, begun 1294, commissioned by the the Franciscans with the support of the Florentine government and private citizens. | |

|

H

|

|

Santa Maria Novella, founded before 1246, nave begun after 1279, commissioned by the Dominicans with the support of the Florentine government and private citizens. The facade was designed by Leonbattista Alberti, c. 1456-70. | |

| I |  |

Santa Maria del Carmine: Brancacci Chapel. | |

| J |  |

|

Church of Ognissanti (built after 1251) was founded by the Humiliati, one of a series of new mendicant orders that emerged in the latter twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. The Humiliati addressed the needs of the growing urban population engaged in commerce and manufacturing. Echoing the values of the original Benedictine monasticism, the Humiliati was a lay congregation dedicated to work and prayer. The Humiliati were especially involved with the cloth industry. The location of the Church of Ognissanti near the river was in the center of the neighborhood dedicated to cloth production. |

| K |  |

|

Sta. Trinità |

| L |  |

Medici Palace, begun 1446, designed by Michelozzo | |

| M | San Lorenzo with the Old and New Sacristies. | ||

| N | San Marco | ||

| O |  |

Mercato Nuovo | |

| P |  |

Strozzi Palace, 1489-1507. | |

| Q |  |

Rucellai Palace, c. 1452-58. The design is attributed to Leonbattista Alberti | |

| R | Santo Spirito, construction begun 1446. Designed by Brunelleschi 1434-36. | ||

See also the Florence Art Guide.

Sassetti Chapel and Institutional Contexts

From at least the fourteenth century the private patron played a critical role in the creation of public images. Individuals would gain the privilege of establishing private chapels and commission artists to decorate these interiors. For example, the Paduan merchant, Enrico Scrovegni commissioned Giotto to paint the Arena Chapel. A commission like this gave public testament to the piety of the patron at the same time as being a visible symbol of the patron's wealth and power. The Sassetti Chapel in the Florentine church of S. Trinità is a good example of such a commission. Francesco Sassetti, descended from an old Florentine family,wanted to make a monument to himself and his family. His first ambition was to gain the rights to the main chapel in the chancel of the church of S. Maria Novella, but the rights to this chapel were granted to the Tournabuoni family. Instead Francesco was granted the rights to the chapel in S. Trinità.

The frescos and altarpiece in the chapel were painted between 1482-86 by the prominent late fifteenth century Florentine painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, who was also responsible for the paintings in the Tournabuoni Chapel in S. Maria Novella.

Examination of one the frescoes in this chapel, Pope Honorius III Sanctioning the Franciscan Order, gives us a visible manifestation of the institutional frameworks of Renaissance life:

The fresco

presents an interesting melding of thirteenth century Rome with fifteenth century

Florence. Pope Honorius III is shown confirming the order to the kneeling St.

Francis. This like the other frescos in the chapel are dedicated to episodes

from the life of Saint Francis. The choice of this subject matter is explained

in part that Francis was the name-saint for Francesco Sassetti.  Could

the choice of subject matter also be a slight to the Dominicans, the Franciscan's

rival mendicant order who controlled S. Maria Novella? Instead of setting the

scene in the Lateran Palace in Rome, Ghirlandaio places the figures in an open

loggia overlooking the Piazza della Signoria.

Could

the choice of subject matter also be a slight to the Dominicans, the Franciscan's

rival mendicant order who controlled S. Maria Novella? Instead of setting the

scene in the Lateran Palace in Rome, Ghirlandaio places the figures in an open

loggia overlooking the Piazza della Signoria.  The Loggia dei Lanzi and the entrance

to the Palazzo Vecchio appear prominently in the background of the fresco. Analysis

of the perspective system of the painting further suggests the importance of

the civic monuments to the meaning of the painting. Tracing the orthogonals

of the linear perspective system demonstrates that the vanishing point corresponds

to the center of the Loggia dei Lanzi. It would from this spot that the Priors

would participate in formal public ceremonies.

The Loggia dei Lanzi and the entrance

to the Palazzo Vecchio appear prominently in the background of the fresco. Analysis

of the perspective system of the painting further suggests the importance of

the civic monuments to the meaning of the painting. Tracing the orthogonals

of the linear perspective system demonstrates that the vanishing point corresponds

to the center of the Loggia dei Lanzi. It would from this spot that the Priors

would participate in formal public ceremonies.

To the right of the pope appears a group which includes from left to right Antonio Pucci (Francesco Sassetti's brother-in-law), Lorenzo de Medici, Francesco Sassetti, and his son Federico. Ascending the stairs at the bottom of the image are the three sons of Lorenzo de Medici, Piero, Giovanni, and Giuliano. These children are led by their tutor, Angelo Poliziano, while other tutors, Matteo Franco and Luigi Polci, follow the group. The prominent position of members of the Medici family in this fresco commissioned by Francesco Sassetti signifies the political and business alliance between these prominent Florentine families. A political rapprochement between Florence and Rome at this period would explain the inclusion of Florence instead of Rome as the setting of the fresco. The humanists, especially Poliziano included in the foreground, attempted to find historical proof of the traditional belief that Florence had been founded by the Romans. The prominence of the Loggia dei Lanzi seems to echo the ties between Florence and Rome when it is remembered that the Florentine Loggia was based on the Basilica of Constantine in Rome.

In examining the fresco notice the number of different institutions that are included in the fresco. These include the Roman church, the Franciscan order, civic institutions of Florence, the family and its patriarchal structure, political alliances through factions, marriage as an institution of political and business alliances, and the cultural life of humanist scholars and of course the role of the artist. In this fresco the spiritual world is brought down into the civic world of fifteenth century Florence, and the fresco's content is much about the ambitions of Francesco Sassetti and his family as it is an illustration of an episode in the life of St. Francis.

|

Family Excerpt from Gene Brucker, Renaissance Florence, p. 90: The family constituted the basic nucleus of Florentine social life throughout the Renaissance, and the bond existing between family members was the strongest cement in the city's social structure. One of its sources of vitality was tradition, the collective memory of a past when family members were forced to unite and act as a group in order to survive. The strong kinship sense of such prominent families ... was nourished by memories of the roles these houses had played in the city's history --the street fights against rival clans, the exploits of their ancestors in battles against Florence's enemies. Physical evidence of this cohesiveness was the concentration of a family's households in one district, along a single street, or surrounding square. Other kinds of evidence survive in written form: in the list of offices and dignities held /p. 91: by members of a family, in the proud claims to family antiquity and distinction recorded in private diaries.... It was to the family that the individual owed his primary obligation: the rank and condition of the family largely determined the course which his own life was to take. The family's status (and this was carefully weighed and measured) established the individual's position in society. The family provided wealth, business and political connections, the opportunity for public office. Not only was a man's bride normally chosen by his father but the paternal choice was limited to those houses similar in rank to his own. Even after a son was legally emancipated from his father, he was bound to his relatives by many ties. A head of a household who planned to marry his daughter would invariably consult with his kind about the choice of son-in-law. Any important decision --the purchase of land, a marriage contract, the making of a will-- was made with the advice and consent of father, uncles, cousins. From this system, which restricted the individual's actions, he received certain positive benefits. He could normally expect his relatives to assist him in case of grave financial need, and to give him support in lawsuits. Although /p. 92: the vendetta was slowly disappearing as a social institution, a scion of a large and powerful family could be secure in the knowledge that only a very bold man would deliberately court the hostility of his kin by attacking him. In a society thus organized around the family, the marriage contract was a document of supreme significance. First, it was an important financial transaction. The size of the dowry was an indication of the economic status of the contracting parties....It was customary for families belonging to the same party or faction to intermarry. Conversely, an alliance contracted with a family in political disfavor was a dangerous and foolhardy enterprise. Marriages were also indices of social status, and of the rise and decline of particular families.... The accounts of births, deaths, and marriages bulk large in the private records of any society, but the space devoted to marriage negotiations in Florentine letters and diaries is conclusive evidence of the importance of this activity in patrician circles.... /p. 93: Together with wealth, anitquity, and the possession of high communal office, marriage connections were the most important criteria for determining social status. And since two of these factors --wealth and political power-- were constantly fluctuating in this volatile society, the status of a particular family was never stable and secure.... |

Artistic Contexts

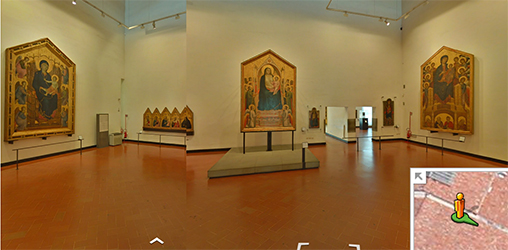

The production and consumption of works or art are historically and culturally relative. The nature of the artist and the function of the work of art are socially and culturally determined. The experience of art in the modern museum tends to neutralize the social and cultural contexts. We tend to see the works deployed to fill their role in the narrative of modern art history. A good example of this is presented by a major gallery in the Uffizi Museum in Florence. [I encourage you to visit the Uffizi on Google Earth. You can "walk" through the different rooms]In this room are some of the major monuments of late thirteenth and early fourteenth century painting including most dominantly Giotto's Ognissanti Madonna, Cimabue's Santa Trinità Madonna, and Duccio's Rucellai Madonna :

|

In the Uffizi, this room initiates the sequence of rooms that follows the narrative of Renaissance painting. In the room itself the Giotto painting is given the privileged position opposite the entrance door and flanked on adjacent walls by the other two paintings. What is emphasized here is the crucial role the Florentine artist Giotto played in the transformation of art to what we might call a Proto-Renaissance art style. As we will see when we consider Giotto, the work establishes a new relationship between itself and the viewer. This view of the painting is not wrong, but it ignores the original function of the work. We need to consider the function of the work as an altarpiece in the context of the liturgy of the church. The analytical and aesthetic perspectives of the modern art historian need to be expanded to include the intense spirituality of the original viewers of this work. A fresco of the Miracle of the Cross in the upper church of Saint Francis in Assisi reminds us of the role religious images played in late Medieval and early Renaissance religion:

Excerpts from Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman's Handbook

|

Sculptor's Workshop. c. 1416, commissioned by the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname from Nanni di Banco for the base of the guild niche at Orsanmichele. |

Cennini was born about

1370 near Florence. He was a pupil of Agnolo Gaddi, who had been a pupil of

Taddeo Gaddi, who in turn was a pupil of Giotto. Thus Cennini is a direct artistic

descendent of Giotto and the inheritor of the traditional practices of the fourteenth

century Italian art workshop.

Here begins the craftsman's handbook, made and composed by Cennino Cennini of

Colle, in the reverence of God, and of the Virgin Mary, and of Saint Eustace,

and of Saint Francis, and of Saint John the Baptist, and of Saint Anthony of

Padua, and, in general of all the Saints of God; and in the reverence of Giotto,

of Taddeo, and of Agnolo, Cennino's master; and for the use and good profit

of anyone who wants to enter this profession.

It is not without the impulse

of a lofty spirit that some are moved to enter this profession, attractive to

them through natural enthusiasm. Their intellect will take delight in drawing,

provided their nature attracts them to it of themselves, without any master's

guidance, out of loftiness of spirit. And then, through this delight, they come

to want to find a master; and they bind themselves to him with respect for authority,

undergoing an apprenticeship in order to achieve perfection in all this. There

are those who pursue it, because of poverty and domestic need, for profit and

enthusiasm for the profession too; but above all these are to be extolled the

ones who enter the profession through a sense of enthusiasm and exaltation.

You, therefore, who with

lofty spirit are fired with this ambition, and are about to enter the profession,

begin by decking yourselves with this attire: Enthusiasm, Reverence, Obedience,

and Constancy. And begin to submit yourself to the direction of a master of

instruction as early as you can; and do not leave the master until you have

to.

The basis of the profession, the very beginning of all these manual operations, is drawing and painting. These two sections call for a knowledge of the following: how to work up or grind, how to apply size, to put on cloth, to gesso, to scrape the gessos and smooth them down, to model with gesso, to lay bole, to gild, to burnish; to temper, to lay in: to pounce, to scrape through, to stamp or punch; to mark out, to paint, to embellish, and to varnish, on panel or ancona. To work on a wall you have to wet down, to plaster, to true up, to smooth off, to draw, to paint in fresco...the next thing is to draw. You should adopt this method.

Having first practiced drawing

for a while as I have taught you above, that is, on a little panel, take pains

and pleasure in constantly copying the best things which you can find done by

the hand of great masters. And if you are in a place where many good masters

have been, so much the better for you. But I give you this advice: take care

to select the best one every time, and the one who has the greatest reputation.

And, as you go on from day to day, it will be against nature if you do not get

some grasp of his style and of his spirit. For if you undertake to copy ofter

one master today and after another tomorrow, you will not acquire the style

of either one or the other, and you will inevitably, through enthusiasm, become

capricious, because each style will be distracting your mind. You will try to

work in this man's way today, and the other's tomorrow, and so you will not

get either of them right. If you follow the course of one man through constant

practice, your intelligence would have to be crude indeed for you not to get

some nourishment from it. Then you will find, if nature has granted you any

imagination at all, that you will eventually acquire a style individual to yourself,

and it cannot help being good; because your hand and your mind, being always

accustomed to gather flowers, would ill know how to pluck thorns.

Mind you, the most perfect steersman that you can have, and the best helm, lie in the triumphal gateway of copying from nature. And this outdoes all other models; and always rely on this with a stout heart, especially as you begin to gain some judgment in draftsmanship. Do not fail, as you go on, to draw something every day, for no matter how little it is it will be well worth while, and will do you a world of good.

Baccio Bandinelli, Self Portrait, c 1530.

This self

portrait by the Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli testifies to the transformation

in the  concept

of the artist since Nanni di Banco's relief. Instead of showing a workshop

with its members actively collaborating on projects, Bandinelli depicts

himself in isolation in a splendid, classical architectural setting. He

wears gold chain with a pendant identifiable as the symbol of the chivalric

Order of St. James (Santiago). As

this gold chain suggests, Baccio Bandinelli fashioned himself as a court

artist. His most important commissions were from the Medici Dukes of Florence

as well as the Papacy. Bandinelli had sought the patronage of the

Emperor Charles V and had presented him with various gifts including a relief

of the Deposition. In response to these gifts Charles V rewarded

Bandinelli with knighthood of the Order of St. James in October 1529. To

support his claim to the title of knighthood, Baccio claimed descent from

the noble family of Bandinelli from Siena. In his Memoriale, Bandinelli writes the following account in which he identifies himself as a courtier of noble status:

concept

of the artist since Nanni di Banco's relief. Instead of showing a workshop

with its members actively collaborating on projects, Bandinelli depicts

himself in isolation in a splendid, classical architectural setting. He

wears gold chain with a pendant identifiable as the symbol of the chivalric

Order of St. James (Santiago). As

this gold chain suggests, Baccio Bandinelli fashioned himself as a court

artist. His most important commissions were from the Medici Dukes of Florence

as well as the Papacy. Bandinelli had sought the patronage of the

Emperor Charles V and had presented him with various gifts including a relief

of the Deposition. In response to these gifts Charles V rewarded

Bandinelli with knighthood of the Order of St. James in October 1529. To

support his claim to the title of knighthood, Baccio claimed descent from

the noble family of Bandinelli from Siena. In his Memoriale, Bandinelli writes the following account in which he identifies himself as a courtier of noble status:

| Being desirous to bring splendor to my lineage, I took the occasion offered by Charles V's trip to Italy...to ask the emperor to induct me into the Order of Santiago. I was a courtier in the suite of the pope, who testified that I was born into the very ancient and very noble house of the Bandinelli of Siena...many princes and lords of the Order ignorantly opposed my nomination, saying that as a sculptor I did not deserve it.... |

Bandinelli celebrated his status as a knight of the Order of St. James in an inscription on the base of his copy of the Laocoon, one of the most revered statues of the ancient world: "Baccius Bandinellus Florentinus Sancti Iacobi Eques Faciebat (Baccio Bandinelli, Florentine and knight of Saint James made this)."

In

Renaissance and Baroque art the gold chain is a regular feature in many self-portraits.

The gold chain signified

status at court and a reciprocal relationship between the artist and ruler.

In return for the ruler's favor and financial support, the court artist was

expected to glorify him and his office. Titian's Self

Portrait illustrates this type

of portrait with a gold chain. In 1533, Charles V appointed Titian Count Palatine and raised him to the rank of a Knight of the Golden Spur. Notice how Titian does not show himself with

the normal "tools of the trade," but is shown wearing a fur coat and satin blouse

appropriate to an individual of high social standing. Contemporary descriptions of Titian identify him as a courtier. Vasari writes: "[He was] extremely courteous, with very good manners and the most pleasant personality and behavior." Dolce presents the following description:

In

Renaissance and Baroque art the gold chain is a regular feature in many self-portraits.

The gold chain signified

status at court and a reciprocal relationship between the artist and ruler.

In return for the ruler's favor and financial support, the court artist was

expected to glorify him and his office. Titian's Self

Portrait illustrates this type

of portrait with a gold chain. In 1533, Charles V appointed Titian Count Palatine and raised him to the rank of a Knight of the Golden Spur. Notice how Titian does not show himself with

the normal "tools of the trade," but is shown wearing a fur coat and satin blouse

appropriate to an individual of high social standing. Contemporary descriptions of Titian identify him as a courtier. Vasari writes: "[He was] extremely courteous, with very good manners and the most pleasant personality and behavior." Dolce presents the following description:

| [H]e is a brilliant conversationalist, with powers of intellect and judgment which are quite perfect in all contingencies, and a pleasant and gentle nature. He is affable and copiously endowed with extreme courtesy of behavior. And the man who talks to him once is bound to fall in love with him for ever and always. |

Service at court usually meant liberation from guild regulations and freedom from the rules that governed the trade. As Chapman writes in her book on Rembrandt Self-portraits (p.51): "The chain did not only signify a painter's rank and achievement. It also had important implications for the status of his profession.... Since chains were traditionally bestowed for intellectual pursuits, they signaled that painters had risen above craftsmen, that painting had entered the liberal arts."

Humanists had redefined painting and sculpture as liberal activities associated with the intellect. Thus the status of the artist was elevated from the more lowly status of Antiquity and the Middle Ages when the practice of art was associated with the mechanical arts and not the liberal arts. Humanists saw the foundation of art in the science of geometry one of the traditional disciplines of the Quadrivium, the four mathematical sciences of the Seven Liberal Arts. Geometry concerned itself with essential reality, the underlying order of nature. Painting and sculpture were also compared with poetry, generally associated with the Trivium which was formed by grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Bandinelli was a writer and poet as well as an artist. He became a member of the literary Accademia Fiorentina in 1545.

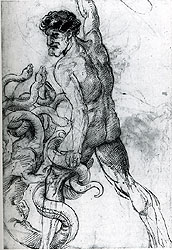

Bandinelli points to a drawing representing Hercules victory over Cacus. The choice of a drawing as opposed to a piece of sculpture was undoubtedly intentional. It is significant that Bandinelli does not show himself as a sculptor with the "tools of the trade." Bandinelli fine clothing and absence of tools disassociates him from the manual practice of the sculptor, while the reference to drawing associates Bandinelli with what was understood as the most intellectual element of artistic practice. Disegno, drawing or design, was the foundation of the Florentine artistic tradition. Vasari, Bandinelli's contemporary and rival, praised Bandinelli's mastery of disegno: "His disegno was praised by experts...." Vasari presents the following definition of disegno, which Vasari sees as the "visible expression and manifestation of the idea which exists in [the mind of the artist]":

Father of our three arts (architecture, sculpture, and painting), disegno proceeds from the intellect, drawing from many things a universal judgment similar to a form or idea fo all the things of nature, which is most singular in its measures (...) [And] from this cognition is born a certain concept (...) such that something is formed in the mind and then expressed with the hands, which is called disegno. One could conclude that this disegno is none other than an apparent expression and declaration of the concept that evolves in the soul(...) When it has derived from [a universal] judgment an image of something, disegno [then] requires that the hand be trained through study and practice to draw and express (with pen, with silver-point, with charcoal or with chalk) whatever nature has created. For when the intellect puts forth concepts and judgments purged [of the accidents of the phenomenal world], the hands that have many years of practice make known the perfection and excellence of the arts along with the knowledge of the artist. |

More specifically disegno focuses on the mastery of the artist to represent the three dimensional form of the human body in two dimensions. Vasari in the following passage emphasizes the importance of the study of the figure as the foundation to art:

The best thing is to draw men and women from the nude and thus fix in the memory by constant exercise the muscles of the torso, back, legs, arms, and knees, with the bones underneath. Then one may be sure that, through much study, attitudes in any position can be drawn by help of the imagination without one's having the living forms in view [Anthony Blunt, Artistic Theory in Italy 1450-1660, p. 90] . |

Artists were challenged to render figures in complex, turning poses and accurately render the skeletal and muscular structure of the body through the contour and modeling of the surfaces of the body. Michelangelo set the standard which all artists attempted to emulate. His mastery of disegno is well illustrated by his drawing for the Libyan Sybil of the Sistine Ceiling and a drawing of male nude.

Raphael

in his drawing of Hercules and the Hydra of about 1508 with its strong emphasis

on contour lines articulating a dramatically turning pose and the modelling

of the bulging muscles demonstrates the impact of Michelangelo on his work.

In learning from Michelangelo, Raphael is also rivalling him. In disegno,

the fundamental principle of all the arts in Florentine eyes, the

artist demonstrated his virtù through his invenzione which

was understood as "the solving of difficult problems and the treatment of

new problems achieved by a lively intelligence." Artists challenged themselves

to present the human body in complex poses. By doing this they overcame difficultà.

The fluid movement or grazia (grace) of these figures also speaks of the artist's demonstration

of sprezzatura, which is the apparently effortless resolution of

difficulty. In conceiving of his disegno shown in his self-portrait

in these terms, Bandinelli was claiming the heroic status of the artist.

As such his choice of subject matter of Hercules and Cacus was undoubtedly

intended to equate the labors of Hercules to that of the Florentine artist. In both the painted drawing and his own pose with their dramatic turning poses, Bandinelli displays his mastery of disegno.

Raphael

in his drawing of Hercules and the Hydra of about 1508 with its strong emphasis

on contour lines articulating a dramatically turning pose and the modelling

of the bulging muscles demonstrates the impact of Michelangelo on his work.

In learning from Michelangelo, Raphael is also rivalling him. In disegno,

the fundamental principle of all the arts in Florentine eyes, the

artist demonstrated his virtù through his invenzione which

was understood as "the solving of difficult problems and the treatment of

new problems achieved by a lively intelligence." Artists challenged themselves

to present the human body in complex poses. By doing this they overcame difficultà.

The fluid movement or grazia (grace) of these figures also speaks of the artist's demonstration

of sprezzatura, which is the apparently effortless resolution of

difficulty. In conceiving of his disegno shown in his self-portrait

in these terms, Bandinelli was claiming the heroic status of the artist.

As such his choice of subject matter of Hercules and Cacus was undoubtedly

intended to equate the labors of Hercules to that of the Florentine artist. In both the painted drawing and his own pose with their dramatic turning poses, Bandinelli displays his mastery of disegno.

The drawing of Hercules and Cacus is also a reference to Bandinelli's most famous public of the same subject made between 1525-34 for the exterior of the Palazzo Vecchio:

Comparison

to the completed sculpture demonstrates that the painting presents a preliminary

version of the sculptural group. The history of this commission teaches us

about the Florentine conception of the artist. When

Michelangelo made his

David it was intended to be paired by a statue of Hercules by Leonardo

da Vinci. The block for this Hercules figure was quarried in 1506. Leonardo's

work on this project never progressed beyond preliminary drawings. Michelangelo

had sought unsuccessfully to receive the commission to complete the pendant

to his own David. Bandinelli received the commission to create the

Hercules figure through his family's connection to the Medici family. The

republican sentiments of many Florentines lead to the hatred of the Medici

Dukes and by association of Bandinelli who was seen as a Medici propagandist.

Michelangelo as well as his followers Giorgio Vasari and Benevenuto Cellini

were very vocal in their attacks on Baccio and his works. Cellini directly

attacked Baccio and lauded Michelangelo before his patron Duke Cosimo de

Medici by reminding the Duke "that marble from which Bandinello made his

Hercules and Cacus was quarried for the marvellous Michelangelo Buonarroti,

When

Michelangelo made his

David it was intended to be paired by a statue of Hercules by Leonardo

da Vinci. The block for this Hercules figure was quarried in 1506. Leonardo's

work on this project never progressed beyond preliminary drawings. Michelangelo

had sought unsuccessfully to receive the commission to complete the pendant

to his own David. Bandinelli received the commission to create the

Hercules figure through his family's connection to the Medici family. The

republican sentiments of many Florentines lead to the hatred of the Medici

Dukes and by association of Bandinelli who was seen as a Medici propagandist.

Michelangelo as well as his followers Giorgio Vasari and Benevenuto Cellini

were very vocal in their attacks on Baccio and his works. Cellini directly

attacked Baccio and lauded Michelangelo before his patron Duke Cosimo de

Medici by reminding the Duke "that marble from which Bandinello made his

Hercules and Cacus was quarried for the marvellous Michelangelo Buonarroti,

who

had made for it a model of a Samson, four figures in all [...]: and your

Bandinello got only two figures out of it." The strong similarities of the

pose of Hercules with its open stance and positioning of the arms to the

figure of St. George by Donatello demonstrate Bandinelli's knowledge of the

work of the great fifteenth century precursor. The similarity of the Hercules to the Donatello is made more evident when it is remembered that the St. George originally had a sword in his right hand corresponding to the club held by Hercules. The apparent borrowing from Donatello was perhaps intended by Bandinelli to be a slight to Michelangelo. The turning motion of the Hercules challenges the

frontality of Michelangelo's David. These details attest to the

intense rivalries that existed among the Florentine artists.

who

had made for it a model of a Samson, four figures in all [...]: and your

Bandinello got only two figures out of it." The strong similarities of the

pose of Hercules with its open stance and positioning of the arms to the

figure of St. George by Donatello demonstrate Bandinelli's knowledge of the

work of the great fifteenth century precursor. The similarity of the Hercules to the Donatello is made more evident when it is remembered that the St. George originally had a sword in his right hand corresponding to the club held by Hercules. The apparent borrowing from Donatello was perhaps intended by Bandinelli to be a slight to Michelangelo. The turning motion of the Hercules challenges the

frontality of Michelangelo's David. These details attest to the

intense rivalries that existed among the Florentine artists.

While the history of the Hercules commission testifies to the rivalry between Bandinelli and Michelangelo, the pose of Baccio's self portrait would be unthinkable without the precedents of the work of Michelangelo. The powerful pose with strong hands and the intensity of his eyes and long flowing beard calls to mind Michelangelo's prophets from the Sistine Chapel and the Moses he made for the Tomb of Julius II:

A comparison of the head of Hercules to the head of the Laocoon shows the unmistakable imprint of this revered ancient statue. The influences of the past and present support Bandinelli's claim to his artistic authority.

SAMPLES

OF ARTISTS' CONTRACTS

The following is a contract signed by the Florentine painter Domenico Ghirlandaio and the Prior of the Spedale degli Innocenti for a painting of the Adoration of the Magi:

Be it known and manifest to whoever sees or reads this document that, at the

request of the reverend Messer Francesco di Giovanni Tesori, presently Prior

of the Spedale degli Innocenti at Florence, and of Domenico di Tomaso di Curado

[Ghirlandaio], painter, I, Fra Bernardo di Francesco of Florence, Jesuate Brother,

have drawn up this document with my own hand as agreement, contract, and commission

for an altar panel to go in the church of the abovesaid Spedale degli Innocenti

with the agreements and stipulations stated below, namely:

This day 23 October 1485

the said Francesco commits and entrusts to the said Domenico the painting of

a panel which the said Francesco has had made and has provided; the which panel

the said Domenico is to make good; and he is to color and paint the said panel

all with his own hand in the manner shown in a drawing on paper with those figures

and in that manner shown in it, in every particular according to what I, Fra

Bernardo, think best; not departing from the manner and composition of the said

drawing; and he must color the panel at his own expense with good colors and

with powdered gold on such ornaments as demand it, with any other expense incurred

on the same panel, and the blue must be ultramarine of the value of about four

florins the ounce; and he must have made and delivered complete the said panel

within thirty months from today; and he must receive as the price of the panel

as here described (made at his, that is, the said Domenico's expense throughout)

115 florins if it seems to me, the abovesaid Fra Bernardo, that it is worth

it; and I can go to whomever I think best for an opinion on its value and workmanship,

and if it does not seem to me worth the price, he shall receive as much less

as I, Fra Bernardo, think right; and he must within the terms of the agreement

paint the predella of the said panel as I, Fra Bernardo, think right; and he

shall receive payment as follows --the said Messer Francesco must give the abovesaid

Domenico three large florins every month, starting from 1 November, 1485 and

continuing after as is stated every month three large florins.

And if Domenico has not delivered the panel within the abovesaid period of time, he will be liable to a penalty of fifteen florins; and correspondingly if Messer Francesco does not keep to the abovesaid monthly payment he will be liable to a penalty of the whole amount, that is, once the panel is finished he will have to pay complete in full the balance of the sum due.

The following is a contract made in 1478 between the Sienese painter Matteo

di Giovanni and the baker's guild of Siena:

Anno Domini 1478, November 30, Antonio da Spezia and Peter Paul of Germany,

bakers, inhabitants of the city of Siena, in the street of maidens, administrators,

as they affirm, elected and deputed for the purpose mentioned below by the Society

of St. Barbara which meets in the church of San Domenico in Siena, for the purpose

of renting the meeting room and for the work on the painting, in their own personal

names ordered and commissioned Matteo di Giovanni, painter of Siena, here present,

to make and paint with his own hand an altarpiece for the chapel of St. Barbara

already mentioned, situated in the church of San Domenico, with such figures,

height and width, and agreements, manners, and arrangements and length of time

noted below, and described in the common language.

First, the said panel is

to be as rich and as big, and as large in each dimension, as the panel that

Jacopo di Mariano Borghesi had made, at the altar of the third of the new chapels

on the right in San Domenico aforesaid, as one goes towards the high altar.

With this addition, that the lunette above the said altarpiece must be at least

one-quarter higher than the one the said Jacopo had made. Item, in the middle

of the aforementioned panel the figure of St. Barbara is to be painted, sitting

in a golden chair and dressed in a robe of crimson brocade. Item, in the said

panel shall be painted the two angels flying, showing that they are holding

the crown over the head of St. Barbara. Item, on side of St. Barbara, that is

on the right, should be the figure of St. Catherine the German and on the left

the figure of Mary Magdalene. Item, in the lunette of the said panel there should

be and is to be represented the story of the three Magi, who come from three

different roads, and at the end of the three roads these Magi meet together,

and go to offer at the Nativity, with the understanding that the Nativity is

to be represented with the Virgin Mary, and her Son, Joseph, the ox and the

ass, the way it is customary to do this Nativity.... Item, to the measurements

mentioned, at his own expense, and have it painted and adorned with fine gold,

and with all the colors, richly, according to the judgment of every good master,

like the one Jacopo Borghesi, and have it set on the altar at his own expense,

in eight months from now, without any variance.

And all these things for

the price of ninety florins, at four pounds the florin, in Sienese money, to

be paid to the said master Matteo in this way and at these times, to wit, 25

florins at the present time, another 25 florins at Easter next, 20 florins on

the Feast of the Holy Ghost next, and the balance to wit another 20 florins,

at the end of the time, and when the said master has completed the painting

in every degree of finish, and placed it on the said altar. Done at Siena, in

the hall of the notaries' guild, in the presence of bakers of Germany, inhabitants

of Siena, witnesses. After which, in the same place, Master John son of the

late Frederick of Germany, embroiderer, and inhabitant of Siena, promised the

said master Matteo to guarantee that the said clients paid the said sums.

Florins are the Best of Kin

The following poem was

written by Cecco Angiolieri of Siena (ca. 1260-ca. 1312)

Preach what you will,

Florins are the best of kin:

Blood brothers and cousins true,

Father, mother, sons, and daughters too:

Kinfolk of the sort no one regrets,

Also horses, mules and beautiful dress.

The French and the Italians bow to them,

So do noblemen, knights, and learned men.

Florins clear your eyes and give you fires,

Turn to facts all your desires

And into all the world's vast possibilities.

So no man say, I'm not nobly born, if

He have not money. Let him say,

I was born like a mushroom, in obscurity and wind.

Significant Guilds:

Arte della Calimala- refiners of imported woolen cloth

Arte della Lana- wool manufacturers

Arte della Cambio- bankers and money changers

Arte dei Giudici e Notai- Judges and notaries

Arte della Seta- silk workers

Arte dei Medici e Speziale- doctors and pharmacists

Arte di Pietra e Legmani- sculptors of stone and wood