Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments

Women in Renaissance Florence

by Dale Kent

( from David Alan Brown, Virtue and Beauty, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., 2001)

p. 26: The modern conception of the Renaissance was shaped essentially by Jacob Burckhardt's 1860 study, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Burckhardt envisioned Renaissance men as rejecting the corporate values that had determined personal identity in the Middle Ages, and Renaissance women as enjoying a new equality with men. He characterized fifteenth-century Italy as the birthplace of modern individualism, often seen as literally represented in Renaissance portraits.

In the last thirty years so so, feminist scholars have reappraised female experience in Renaissance Italy, as elsewhere. Gender is now generally viewed as a social construct as much as a biological given, and women as universally constructed in accordance with the male needs and ideals of the specific societies in which they lived.

Art historians have reassessed the representation of women by male writers and artists of the Renaissance in the light of psychological insights derived from critical writing on the cinema, in which males are seen to assert power through the privileged subjective action of looking at females, the passive, powerless object of their controlling gaze, she the eternal "other" to his "self."

Social historians, studying the structure and ideology of the male lineage and of the Florentine republic, have explored the social and legal constraints on women and demonstrated that female destiny was almost entirely in the hands of men; indeed, women had very limited rights and few opportunities for any autonomous action.

They have also shown that, in fact, neither men nor women were free, as Burckhardt imagined, to fashion an individual self, a personal identity independent of the values and demands of a society still structured around the communities of family, state, and an all-pervasive Church. Their values determined the very different roles of men and women in a social scenario to which both sexes were committed. Portraits, like most Renaissance images, represent a complex amalgam of real and ideal, signified by idealized features and stylized attributes, in the presenation of a self as defined by society.

"Don't be born a woman if you want your own way." This dictum of Nannina de' Medici, from a letter to her brother Lorenzo the Magnificent, written after an altercation with her father-in-law, Giovanni Rucellai, shortly after her marriage to his son Bernardo, holds true of even the most privileged of Florentine upper-class women.... Indeed, Florence was among the more unlucky places in Western Europe to be born a woman. In the princely courts a woman could inherit wealth and a measure of power with her noble blood, and her significance might then be as much dynastic as domestic, even political.

In Florence, inheritance was through the male line only. The merchant republican society of that city was committed to communal, Christian, and classical values. These all prescribed that the honor of men should reside in their public image and service, and in the personal virtue of their wives; women were excluded from public life, and sequestered in the home to ensure their purity and that of the blood line through which property descended.

In their portraits women appear framed in the windows of their houses. In 1610 a French traveler commented after a visit to Florence that "...women are more enclosed [here] than in any other part of Italy; they see the world only from the small openings in their windows...."

Historians are often hard put to rescue the testimony of women's experience from the silence imposed on them by the limitations of evidence produced largely by men. In Florence, the best documented society of early modern times, men restricted women's lives, but as almost obsessive record keepers kept account of them. In the words of Renaissance laws, tax returns, and sermons, as well as women's own letters and devotional writings, we may still hear something of their voices.

Women's lives

throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance were strongly shaped

by the ambivalent attitudes of a powerful Church whose moral prescriptions

were enforced not only in the confessional, /p. 27: but also by the laws of

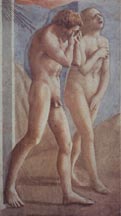

the state.  Eve

was the villainess of Christian history, the cause of original sin and of

man's Fall. God created her from Adam's rib, subordinate. But she was tempted

by the serpent, and tempted Adam to sexual sin. Thus Everywoman dwelt in the

shadow of the fallen Eve, justly sentenced to the pain of childbirth and the

labor of motherhood. The stereotype of woman as Eve was that she was weak,

foolish, sensual, and not to be trusted. Women were the scapegoats for the

physical impulses that warred perpetually with the spiritual in men, a conflict

sometimes depicted as an allegory of marriage. Self-disgust and revulsion

against women are typically mingled in an adage of the humanist scholar Marsilio

Ficino: "Women should be used like chamber pots: hidden away once a man

has pissed in them."

Eve

was the villainess of Christian history, the cause of original sin and of

man's Fall. God created her from Adam's rib, subordinate. But she was tempted

by the serpent, and tempted Adam to sexual sin. Thus Everywoman dwelt in the

shadow of the fallen Eve, justly sentenced to the pain of childbirth and the

labor of motherhood. The stereotype of woman as Eve was that she was weak,

foolish, sensual, and not to be trusted. Women were the scapegoats for the

physical impulses that warred perpetually with the spiritual in men, a conflict

sometimes depicted as an allegory of marriage. Self-disgust and revulsion

against women are typically mingled in an adage of the humanist scholar Marsilio

Ficino: "Women should be used like chamber pots: hidden away once a man

has pissed in them."

Conversely,

Christian teaching held the potential for an immense respect for women and

specifically female functions elevated to their highest degree in life of

the Virgin Mary. Even if, according to an early Christian writer, "Alone

of all her sex/ She pleased the Lord," she who was ultimately pure, born

of an Immaculate Conception and destined to be the virgin mother of Christ,

opened the way to a more positive view of women by redeeming the sin of Eve.

Contemplating the Annunciation, the influential philosopher and theologian

Peter Damian reflected: "That angel who greets you with 'Ave'/ Reverses

sinful Eva's name. / Lead us back, O holy Virgin / Whence the falling sinner

came.'

Conversely,

Christian teaching held the potential for an immense respect for women and

specifically female functions elevated to their highest degree in life of

the Virgin Mary. Even if, according to an early Christian writer, "Alone

of all her sex/ She pleased the Lord," she who was ultimately pure, born

of an Immaculate Conception and destined to be the virgin mother of Christ,

opened the way to a more positive view of women by redeeming the sin of Eve.

Contemplating the Annunciation, the influential philosopher and theologian

Peter Damian reflected: "That angel who greets you with 'Ave'/ Reverses

sinful Eva's name. / Lead us back, O holy Virgin / Whence the falling sinner

came.'

Devotional images depicted the Virgin Mary in roles which were the common lot of womankind: the Annunciation of her pregnancy, giving birth in the stable of the Nativity, the Madonna and Child, the infant cradled in his mother's arms, her grief at his death at the Crucifixion. These archetypal images framed society's views of real women, furnishing exemplars for their behavior. San Bernardino, the most popular of Tuscan preachers in the fifteenth century, enjoined his female listeners to model themselves on the Virgin as depicted in Simone Martini's Annunciation: "Have you seen that [Virgin] Annunciate that is in the Cathedral, at the altar of Sant' Ansano, next to the sacristy?... She seems to me to strike the most beautiful attitude, the most reverent and modest imaginable. Note that she does not look at the angel but is almost frightened. She knew that it was an angel.... What would she have done had it been a man! Take this as an example, you maidens."

Marriage and the dowry system were the major determinants of female destiny. Rather than the consensual union of two individuals, marriage was a social and economic contract between families that answered to their interest and that of the state in replenishing a population threatened by recurring episodes of plague. As Francesco Barbaro stressed in his famous treatise concerning wives presented to Cosimo de' Medici's brother Lorenzo when he married Ginevra Cavalcanti, the first duty of a man was to marry and increase his family. A woman's primary function was to serve as the vessel by which the lineage /p. 28: was maintained. A woman's secondary function was as the means of attaching to the lineage by marriage allies from other Florentine families with desirable attributes --wealth, nobility, and political influence; she acts as "a sort of social glue."

As anthropologists have observed, the exchange of women in traditional societies is a conversation between men; it is also the basis of all symbolic exchange. The symbolic exchanges associated with marriage were negotiated in meetings between the men of the two families. Their alliance was sealed in a series of social rituals centered on contracts preceding it, the exchange of gifts and rings, and wedding banquets intended as a conspicuous display of the groom's social position and assets. In a spalliera panel painted for the marriage of Giannozzo Pucci and Lucrezia Bini in 1483, expensive plate is displayed in the foreground, the coats of arms of the couple are prominently placed on the exterior columns, and Lorenzo de' Medici, who arranged the match, is represented by his family arms on the central column, by the symbolic laurel bushes and by his device of the diamond ring....

A mid-fifteenth-century painted panel, probably to decorate a bedchamber, depicts the marriage procession in the public setting of the piazza of the Baptistery; the lily of Florence on the banners attached to the instruments of the accompanying musicians underscores the civic significance of the union. Elaborately dressed guests perform a dance, and preparations for a banquet are also visible.

The dowry was the major component of the marriage exchange, but in Florence it was augmented with gifts from the bride's kin and counter-gifts from her husband and his family. The expenses of contracting an honorable union were considerable on both sides. Patrician men postponed marriage until their early thirties, waiting, perhaps, to accumulate a respectable fortune. Young women were usually betrothed between twelve and eighteen, to ensure that they came to the wedding bed as virgins....

"Birds of passage" in a no-woman's land between the two male lineages to which they half belonged, women were caught between competing kinship strategies. At her husband's death a woman had either to return to her natal family, which was sometimes unwilling or unable to reshoulder the financial burden of her support, or to remain, often under sufferance, with her in-laws; women were considered far too dangerous and untrustworthy /p. 29 to be allowed to live alone. "It was of course the dowry that tangled the threads of a woman's fate." Theoretically, the dowry that a woman brought her husband was attached to her for life, to provide for their household during his lifetime and for her after his death. But since the potential loss if she left with her dowry threatened the economic equilibrium of her deceased husband's household, it was usually in the interests of his heirs to persuade her to remain with them. If she was over forty, the unlikelihood of finding her a new husband, due to the premium placed on virginity at marriage and the potential to produce heirs, and the difficulty of assembling dowries, discouraged her own family from intervening.

If she were still young, however, a widow might be pressured to return to her family of birth and once again become a card to play in their matrimonial strategies. In this case she left with her dowry, but without her children....

The fifteenth century saw the extreme inflation of the sum of money required by a bride's family to procure a groom of suitable status. Since many fathers came to dread the birth of daughters, not only because of their intrinsic lack of worth, but also because of the financial burdens they represented, to encourage the institution of marriage the Florentine state established a dowry fund --the Monte delle Doti....

Complicating the financial arrangements of marriage were the subsidiary exchanges it involved. The money paid out by the bride's family for the dowry was accompanied by the trousseau (donora), which consisted of clothes and small personal items. This was scrupulously divided into two parts, those items "counted" or "not counted" by the officiating notary. Legally belonging to the bride, her "personal property" was nevertheless not hers to dispose of as she wished, and at the death of either spouse it was often hotly contested. Some small everyday objects like dolls, needles, and prayer books, often depicted in portraits to signify a woman's possession of female virtues, might be passed on to her female descendants. The dowry reverted to the males of her lineage after her death....

Presentations to the bride from the bridegroom and his family functioned as a "counter-dowry," returning /p. 30: equilibrium to an unbalanced economy of exchange. The husband's gifts to the bride were also divided into two parts, including a cash gift corresponding symbolically to the dowry, addressed to the bride's kin, and the mancia ("tip" in modern Italian) traditionally given to proclaim the consummation of the marriage. The groom's gifts to the bride appropriately consisted of body ornaments, the sumptuous clothes and jewels --shoulder brooch, head brooch, and pendant-- displayed in portraits. "Marking" her with dresses and jewels, often bearing his crest, by bestowing on her a ritual wedding wardrobe the husband introduced his wife into his kin group and signaled the rights he had acquired over her. Most of these items remained the property of the husband, who might later bequeath them to his wife or repossess them; if he needed the capital, they could be sold.

Although sumptuary laws proved perenially difficult to enforce, throughout the history of the republic officials of the state made periodic attempts to restrict extravagant private display of wealth and honor in marriage gifts, wedding banquets, baptisms, and funerals.... Among several possible explanations for the persistence of such laws in the face of the acknowledged importance of display in Florentine culture is this patriarchal society's negative attitude toward women....

/p.31: Both men and women in this society were preoccupied with personal appearance because dress was a way of displaying and distinguishing status and dignity, occupation and occasion, not simply wealth. Cosimo de' Medici pressed upon Donatello a gift of clothing appropriate to the dignity of his artistic genius....

A progressive relation of the prescriptions of Florentine sumptuary laws from the beginning of the fifteenth century to the 1460s was followed in the 1470s and 1480s by a reaction --possibly to the failures of enforcement of the preceding half-century-- and many fourteenth-century limitations were restored. In the absence of any clearly explanatory evidence, one might speculate that the crackdown in the 1470s was related to a possible wish on Lorenzo [de' Medici's] part to curb competitive displays by his fellow oligarchs. In view of the claim that extravagance in female dress cut into the groom's accession of capital, the spate of bank failures that hit many upper-class families hard in the early 1470s might also be seen as relevant.

Much legislation insisted on the primacy of maintaining what were seen as the traditional Florentine values on which the republic had been built, thrift and austerity, at a time of rapidly expanding consumerism. Above all, fluctuating sumptuary law parallels the constant tension between a view of women as objects of desire, which encompasses a male wish to use female bodies to display the accumulation of wealth and power, and fear, both of women and of God's wrath at excessive ostentation. Always a theme of clerical comment, by the end of the century, in a climate of increasingly intense religious observance and awareness of sin, concern about women's appearance climaxed in Savonarola's movement for the "self reform of women" and in his "bonfires of the vanities."

The obligations of marriage, in accordance with familial and Christian expectations, were outlined in popular literature --stories, poems, sermons, and works directed specifically toward women....From the Church's point of view, the duties of a husband were to instruct, correct, cohabit, and support; his wife was to respect, serve, obey, and if necessary admonish. Their reciprocal obligations were affection, fidelity, honor, and the marital debt....

Once she had been removed to her new family, a stranger within its ranks, a wife's identity derived entirely from that of her husband, whose interests she was expected to put before those of father, brothers, or even children. Her movements were circumscribed by the walls of the family palace....

Within her home, the physical conditions of a woman's life were determined by constant childbirth.... /p. 32: High fertility was in the interests of the male lineage, and given the extremely high rate of mortality (approximately half of all children born died before the age of two, and half of those who survived their first two years were dead before they reached sixteen), women bore the brunt of the need to produce male heirs....

/p. 34: While constant childbearing exhausted women and imperiled their lives, childlessness was a fate still worse, depriving them of worth and honor. Lists of household expenses include payments for various remedies for infertility....

/p. 35: While the home was particularly the province of women, in Florence the distinction between a private, female realm and the public, male world is not so easily made as some have argued....

/p. 36: Moreover, while women undoubtedly spent a disproportionate amount of time in them, bedrooms were by no means off-limits to visitors; indeed, men customarily entertained and consulted with relatives, allies, business associates, and even strangers in their chambers. A well-born Florentine woman had no place in the public life of the streets and palaces of government, but the mistress of a large and wealthy patrician household was far from isolated; the world, in a sense, came to her.....

/p. 40: While Leonardo sought to capture beauty in all its forms, Domenico Ghirlandaio, on the frescoed walls of the family chapels of the Sassetti and Tornabuoni, produced portraits of individuals embedded in the groups of kinsmen, friends, and neighbors that were their social context.

See also the website that accompanies the exhibition: Virtue and Beauty.

Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments