Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 214 Assignments | ARTH 294 Assignments

Allen S. Farber

State University of New York College at Oneonta

Considering

a Marginal Master:

The Work of an Early Fifteenth Century Parisian Manuscript Decorator*

( draft for a paper published by Gesta, 32 (1993), 21-39.)

In the Cité des Dames, Christine de Pizan, responding to Raison's account

of women artists of Antiquity, describes the work of a contemporary female artisan,

Anastasia:

| ... Regarding what you say about women expert in the art of painting, I know a woman today, named Anastasia, who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris -- where the best in the world are found -- who can surpass her, nor who can paint flowers and details as delicately as she does, nor whose work is more highly esteemed, no matter how rich or precious the book is. People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the ornamental borders of the great masters. |

Christine de Pizan's praise of the works of Anastasia provides valuable insights

into the workings of the Parisian book industry of the early fifteenth century.

It suggests that women might play a role in the making of manuscripts. The reference

to "manuscript borders [vignettes d'enlumineure en livres] and miniature

backgrounds [champaignes d'istoires]" also hints at a division of labor

in book production. Despite a recent proposal that Anastasia was responsible

for the "more important" aspects of manuscript making, Henri Martin's

conclusion that she was a specialist in the secondary decoration of manuscripts

remains valid; and presumably the pages decorated by Anastasia had miniatures

painted by other craftsmen. However, fine decorative work in manuscripts was

admired, as Christine's phrase "vignettes des grans ouvriers" indicates.

The talents of an artisan like Anastasia would have been sought after in the

production of deluxe books.

The subject of the present

study, one of the decorators of the Belles Heures of Jean de Berry, may have

been among Christine de Pizan's "grans ouvriers." The decoration of

the Belles Heures was produced by a division of labor. Although overall unity

and coherence were essential concerns, examination of individual motifs in the

text and border decoration suggests a clear division into distinct families,

each family is marked by consistent treatment of the decorative motifs. Integrity

both in repertoire and treatment of decorative motifs suggests that a single

hand was responsible for each family. In all, four distinct hands have been

isolated. The present study will focus on the work of the decorator whom I have

dubbed the A Master. I will examine this individual's responsibilities and working

methods; explore the relationship of our artisan to other craftsmen; attempt

to define the status of this decorator working in the book industry; and trace

the master's career over a period of about fifteen years.

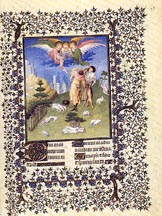

Penned rinceaux with tendrils

formed by a curl terminated by a comparatively tight curlicue almost serve as

a signature for the work of the A Master (Figs. 1 and 2). This motif is consistently

associated with other distinctive decorative forms, for example, the cornerpieces

intersecting with the horizontal framing staff below the center of the lateral

lobe. The sawtooth ink outlining of the cornerpieces and centerpieces is also

characteristic of this hand. Finally, the upper terminals of his vertical staffs

regularly consist of a loop with a circlet or dot. His decorated initials have

similar terminals (Fig.

3).

(Fig.

3).

The characteristic working

habits of the A Master are revealed throughout his decorative pages in the Belles

Heures. For example, on fol. 204r his distinctive tendrils appear in the penned

rinceaux as well as the yellow stems of the red and blue petalled fleurettes

scattered in the border (Fig. 3). The characteristic sawtooth outline of the

cornerpieces is also found in the outline of the gold strip along the back of

the dragon at the top of the page. The painted initial "B" and painted

body of the dragon both are highlighted by a finely serrated white line in combination

with a row of circlets and dots. The foliage in the border, the elaborate staff,

and the initials is all marked by sharply cusped leaves. In a more general stylistic

sense, sharp serrated or sawtooth patterns and outlines reflect the predilections

of one hand, a penchant even evident in the sharply cusped outline of the dragon's

wing.

To date, I have been able

to identify the work of the A Master of the Belles Heures in eleven other manuscripts:

1) Bayeux, Bibliothèque

du Chapitre, MS 61 (now Caen, Archives Départmentales du Calvados), Pontifical-Missal

made for Étienne Loypeau, the Bishop of Luçon (Fig.

13)

2) London, British Library, MS Add. 29433, Book of Hours (Fig.

25)

3) London, British Library, MS Egerton 2709, Conquête et les conquérants

des Iles Canaries (traditionally titled Le Canarien) (Fig. 27)

4) New York, Morgan Library, MS M. 515, Book of Hours, use of Nantes, dated

1402 (Fig.

12)

5) Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 144, Book of Hours, datable to between

the end of January and the end of March of 1408 (Figs. 16 and 17)

6) Oxford, Keble College, MS 11, Hours of the Virgin, textually related to Nantes

(Fig. 28)

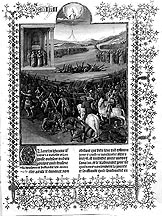

7) Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 247, Flavius Josephus, Les antiquités

judaïques, made for Jean de Berry but left unfinished at the time of his

death in 1416 (Fig.

6)

8) Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 282, Valerius Maximus, Faits

et dits mémorables , the presentation copy of a new French translation

presented to Jean de Berry on New Year's Day 1402 by Jacques Courau, the duke's

treasurer (Figs. 5

and 10)

9) Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 616, Gaston Phoebus, Livre de

la Chasse and Gace de La Buigne, Déduits de la chasse (Fig. 19)

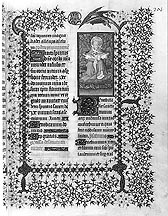

10) Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS nouv. acq. lat. 3107, St. Maur

Hours (Figs. 4,

9,

and 29)

11) Whereabouts unknown, formerly Dyson Perrins collection, Book of Hours, use

of Nantes (Figs. 7

and11)

Examination of the work attributed to the A Master in these manuscripts reveals remarkable consistency in the treatment of the text and border decoration. The distinctive tendrils of the penned rinceaux as well as many of the other decorative components evident in the A Master's work in the Belles Heures are found regularly in these other manuscripts. The master's elaborate staffs may serve for purposes of demonstration. They are characterized by a definable repertoire of motifs. For example, intertwining stems with projecting painted leaves and alternating gold quatrelobes and diamonds marking the intersections of the stems occur in the decoration of the Belles Heures (Fig. 3), the St. Maur Hours (Fig. 4), MS fr. 282 (Fig. 5), and MS fr. 247 (Fig. 6). A variant of this motif appears in the Dyson Perrins Nantes Hours (Fig. 7).

Another motif, consisting

of clusters of ivy leaves weaving back and forth on alternate sides of a central

stem, recurs in pages by the A Master in the Belles Heures (Fig. 8),

the St. Maur Hours (Fig. 9),

MS fr. 282 (Fig. 10),

the Dyson Perrins Nantes Hours (Fig. 11), Morgan MS M. 515 (Fig. 12),

and the Pontifical-Missal of Étienne Loypeau (Fig. 13).

It should be emphasized that none of the decorators with whom the A Master collaborated

used these motifs., nor do precisely the same motifs appear in the work of any

other contemporary decorators of French books of the period.

This evidence suggests the

existence of a personal pattern book of decorative designs from which the A

Master freely quoted. Such a model book probably would have contained not only

designs for elaborate staffs, but also patterns for decorated initials, line

endings, and various border elements. Recent studies have demonstrated the important

role model books played in the illumination of later medieval manuscripts, and

the existence of such a pattern book for decorators has been shown by Janet

Backhouse's publication of such a book in the British Library. This sketchbook,

probably used by an English craftsman of the middle of the fifteenth century,

contains a variety of decorative alphabets as well as suggestions for border

elements and designs for the lay-out of initials and borders for the principal

text pages.

A more detailed examination

of the staffs of the A Master provides even stronger evidence for the use of

such a pattern book. Careful measurement of their components frequently reveal

striking correspondences. For example, the components of the staffs composed

of intertwined stems with alternating quatrefoils and diamonds in the Belles

Heures, the St. Maur Hours, and MS fr. 282 are almost identical in measurements

(Fig. 14 a). A similar comparison of the staffs of bunches of ivy leaves weaving

back and forth along a central stem in the Belles Heures, the St. Maur Hours,

and MS fr. 282 also reveals significant similarities (Fig. 14 b). There are,

however, some differences in the size of these motifs in other manuscripts of

the group. For example, the motif of intertwined stems and alternating diamonds

and quatrelobes on  fol.

70r of MS fr. 247 ( Fig. 6)

is larger than the same motif in the other manuscripts, an enlargement possibly

explained by the considerably larger overall dimensions of the manuscript compared

to the Belles Heures and the St. Maur Hours. In MS fr. 282, however, also a

comparatively large manuscript, the A Master made the components of the staff

the same size as in the Belles Heures, and they do seem to be out of proportion

to the rest of the page (Fig. 5).

fol.

70r of MS fr. 247 ( Fig. 6)

is larger than the same motif in the other manuscripts, an enlargement possibly

explained by the considerably larger overall dimensions of the manuscript compared

to the Belles Heures and the St. Maur Hours. In MS fr. 282, however, also a

comparatively large manuscript, the A Master made the components of the staff

the same size as in the Belles Heures, and they do seem to be out of proportion

to the rest of the page (Fig. 5). These correspondences in size suggest that the A Master employed some tracing

technique to duplicate the staffs in the various manuscripts. James D. Farquhar

demonstrated the use of tracing by a northern French craftsman of the middle

of the fifteenth century for the design of miniatures. He included in his study

a useful discussion of possible tracing techniques, but, unfortunately, it has

not been possible to identify the technique employed by the A Master.

These correspondences in size suggest that the A Master employed some tracing

technique to duplicate the staffs in the various manuscripts. James D. Farquhar

demonstrated the use of tracing by a northern French craftsman of the middle

of the fifteenth century for the design of miniatures. He included in his study

a useful discussion of possible tracing techniques, but, unfortunately, it has

not been possible to identify the technique employed by the A Master.

A study of the division

of labor in the decoration of the manuscripts to which the A Master contributed

gives us important information about the responsibilities of the individual

decorator, the relationship of the various makers, and the production of individual

manuscripts. The division of labor in the decoration of the Belles Heures lends

support to the chronology of production of the Cloisters manuscript proposed

by John Plummer on the basis of an examination of the physical structure of

the book. The early portions of the decoration were almost entirely executed

by the A Master's principal collaborator in the Belles Heures, the B Master.

It was only after the manuscript underwent a major change in plan with the augmentation

of the illustrative program that the A Master became involved. In the last two

major textual units of the manuscript, the two decorators shared in the responsibility

of decoration.

A similar picture is presented

by the division of labor in the Valerius Maximus manuscript (MS fr. 282). Here,

the A Master did the decoration of the first twenty-three gatherings, while

three other decorators shared the responsibility for the remainder of the book.

Although one illuminator was usually responsible for all the decoration of a

gathering, there are instances where the decorators divided individual gatherings

by bifolia. The greater complexity in the division of labor in the latter portions

of MS fr. 282 suggests that the makers were under pressure to finish the work

in time to present the manuscript to the Duke of Berry "à estraines

le I, Janvier 1402 [n.s.]" (New Year's Day) just a little more than three

months after Nicholas of Gonesse finished the translation of the text on "la

veille Saint Michiel l'archange" of 1401 (28 September).

In contrast to MS fr. 282

where the A Master was given responsibility for complete gatherings, in the

St. Maur Hours ( MS nouv. acq. lat. 3107) the A Master's activity was primarily

limited to individual bifolia containing miniatures. The project was apparently

divided between six different decorators, and generally a number of them collaborated

on individual gatherings. The relatively complex division of labor in the St.

Maur Hours can be attributed to time pressure and wealth of decoration. Every

text page of the manuscript has a staff around three sides of the page and gold

leafed penned rinceaux filling the borders.

For these artists, the bifolium

was clearly the basic unit of work, with a single craftsman being responsible

for its entire text and border decoration. The decoration of MS Douce 144, however,

presents important exceptions to this almost universal rule. The luxuriant acanthus

borders of miniature pages (Fig. 15) suggest the work of a specialist distinctly

different from the Belles Heures A Master. Evidence for this conclusion is found

in the border decoration of fol. 28r, which contains the Annunciation miniature

introducing Matins of the Hours of the Virgin. The decoration of the verso (Fig.

16) and both pages forming the conjugate folio can be attributed to the A Master,

but the acanthus border on the miniature page (Fig. 15) has no precedent in

the work of the A Master. The three-line initial "D," however, has

the A Master's characteristic serrated white line highlighting the body, and

the one-line initial "E" has the A Master's characteristic terminals.

The motifs in the line-endings can also be associated with those used by the

A Master in other manuscripts. This suggests that the A Master was responsible

for all of the text decoration of this bifolium and for the borders of the text

pages, but that the border of the miniature page was left blank for the contributions

of a miniature border specialist. This pattern of division of labor appears

to be the rule for bifolia containing miniatures in MS Douce 144.

Such a division of labor

is not unique among books of the period. It can be found, for example, in books

attributed to the Master of the Brussels Initials, an Italian craftsman active

in Paris who frequently decorated the borders surrounding the miniatures while

the decoration of the text pages was left to others. The practice is also evident

in the De Levis Hours in the Beinecke Library at Yale (MS 400), as well as in

an unfinished Book of Hours in the Morgan Library (MS M. 358). In the Morgan

manuscript, as Robert Calkins observed, the opening miniatures and borders at

several text divisions remain unexecuted, while the borders and text decoration

of the conjoint leaves were completely finished. The same division of labor

can also be found in the Belles Heures itself, with the Limbourgs responsible

for the border and the miniature at the opening of Matins of the Virgin and

apparently also for those of a now lost page opening the Gospel Sequences.

MS Douce 144 presents other

significant exceptions to the rule that a single decorator was responsible for

the entire border and text decoration of a bifolium. The decoration of folio

122 verso, for example, is unmistakably that of the A Master (Fig. 17), with

its distinctive tendrils and sharply cusped outlines of the leaves and centerpiece

of the staff. These elements are clearly distinguishable from those on the recto

of the leaf (Fig. 18). Although the tendrils are formed by a curl and curlicue

like the A Master's, the decorator of the recto used a thinner nibbed pen and

the curlicues are less taut and more drawn-out. Nor do the leaves and centerpiece

have the sharply cusped black ink outlines characteristic of the A Master. These

details suggest that the recto was done by a different decorator. But other

decorative elements associated with the decorator of the recto of fol. 122 demonstrate

close affinities to the work of the A Master. For example, the terminals of

the staff have a white circle indistinguishable from those of the A Master.

The initials, likewise, have the A Master's curl and circlet terminals, and

the bows of the two-line initial "O" have the serrated line characteristic

of the A Master's initials. The close relationship of these decorators is also

suggested by their repeated collaboration in MS Douce 144. They worked together

again in the Livre de la chasse in the Bibliothèque nationale (MS fr.

616), where, for example, the decoration of fol. 105v can be attributed to the

A Master (Fig. 19), while that of fol. 109v can be attributed to his associate

(Fig. 20). Their relationship with each other appears to be closer than that

of either with any of the other decorators in these manuscripts. Perhaps it

was a matter of master and apprentice. That the A Master was an established

decorator well before MS Douce 144 was illuminated suggests that the other artisan

was a subordinate, an assistant, or an apprentice.

The relationship of the

A Master with this presumed assistant raises the question of his collaboration

with other specialists working in the Paris manuscript industry. Since the work

of the A Master is found in books with miniatures executed in a wide variety

of styles, he could not have been simply an assistant working in the shop of

a single miniaturist. Significantly, his collaboration with fellow decorators

follows no consistent pattern. In the eleven books associated with the A Master,

the work of at least twenty other decorators can be found. The A Master collaborated

with only three of these decorators more than once. First was his assistant

in the Oxford Hours (MS Douce 144) and the Paris Livre de la Chasse (MS fr.

616). Second was another decorator whose work can be found in the same two manuscripts.

A comparison of fol. 44r of MS Douce 144 (Fig. 21) with fol. 37v of MS fr. 616

(Fig. 22) shows the hallmark motifs of this decorator, penned rinceaux with

the simple curl terminals and five gold balls interconnected by a penned line.

As for the work of the A

Master himself in MS Douce 144 and MS fr. 616 (Figs. 16 and 19), it is virtually

identical in the two manuscripts. In both he frequently replaced his more usual

gold ivy leaves with gold tear-drop, ciliate leaves, a motif he employed rarely

in other manuscripts, and he used two types of fleurettes not found in his other

work. One is a quatrelobe with each lobe divided along its length, half blue

or magenta and the other half highlighted in white. The other fleurette is also

a quatrelobe, but here each lobe is blue with the outside highlighted in white.

The near identity of the A Master's work in MS Douce 144 and MS fr. 616 suggests

that they are contemporaneous. Like MS Douce 144, firmly dated to 1408, MS fr.

616 would have been made in the latter part of the first decade of the fifteenth

century, consistent with the conclusions of other scholars, based on miniature

style.

This dating is given further

support by the decoration of the frontispiece of MS fr. 616. The original decoration

was augmented by the addition of an elaborate staff with penned and painted

rinceaux along the outside border of the page (Fig. 23). The boldly curling

patterns of the penned rinceaux in the outside margin contrast with the rather

unsure, scratchy penned line of the rinceaux on the inside border. A comparison

of the outlining of the leaves and the tendrils of the penned rinceaux proves

that two different decorators were responsible. While the decorator of the inside

margin continued to work in the remainder of the first part of the manuscript,

the decorator who executed the outside margin worked only on this page. This

latter hand can be identified as the A Master's principal collaborator in the

decoration of the Belles Heures, the B Master (Fig. 24). The curling patterns

of the rinceaux, the tendrils formed by a comma stroke followed by a dash and

terminated by an "S" curve, and the interspersing of gold or painted

balls in the rinceaux link the border segment of MS fr. 616 with the decoration

of the Belles Heures. The appearance of both the principal decorators of the

Belles Heures -- the A Master and the B Master-- in MS fr. 616 is not surprising

considering that the manuscripts are contemporary, the Belles Heures having

been completed in 1408 or early in 1409, a date consistent with that already

proposed for MS fr. 616.

MS fr. 616 is not the only

manuscript which shows the collaboration of the A and B Masters of the Belles

Heures. In a Book of Hours in the British Library (MS Add. 29433) they even

shared the decoration of a single bifolium. The A Master's distinctive tendrils

formed by a curl and terminated by a tight curlicue are found on fol. 22v (Fig.

25), and the B Master's characteristic tendrils formed by a comma stroke followed

by a dash and terminated by an elongated "S" curve are found on the

recto of the same leaf (Fig. 26). The quatrefoils in the cornerpieces on the

verso have the A Master's sawtooth outlining, while the cornerpiece on the recto

can be identified as a type used by the B Master in the Belles Heures. Even

the text decoration of these two pages maintains the distinction between the

two. The initials on the recto have the B Master's curl terminals, and those

on the verso have the A Master's curl and dot terminals. Except for the substitution

of painted for penned rinceaux, the decorative system of this bifolium is the

same as that on text pages of the Belles Heures. Both the similar decorative

systems and the collaboration of the principal decorators of the Belles Heures

argue for a dating of MS Add. 29433 to the period when the Cloisters book was

under production.

The collaboration of the

A Master with other decorators is best explained by the particular circumstances

of production of these books. We can reasonably assume that a planner would

call upon the same specialists for any projects that were being carried out

concurrently. But the limited number of instances of the A Master's repeated

collaboration with other decorators does not support the hypothesis of the existence

of a large workshop of which the A Master was a member. In fact, the large overall

number of identifiable hands involved in the decoration of these manuscripts

argues against the existence of such a shop. In MS Douce 144 and MS fr. 616

alone, nine distinct decorators can be identified, and of these, only three

worked on both manuscripts. There is, therefore, no consistent pattern of associations

of the A Master with a specific group of scribes, miniaturists, or fellow decorators,

all members of a single large workshop.

The lack of a consistent pattern of collaboration supports the conclusion that the A Master was an independent craftsman who was called in on an ad hoc basis to contribute to the decoration of specific manuscripts. It would not be necessary for the various decorators collaborating on a particular project to work in the same shop; they could have carried out their work in their own ateliers. Contacts among artisans were facilitated by the tendency of individuals involved in the manuscript trade to live in close physical proximity to each other. It is well known that the area around the church of Saint Severin was an important center of book production. The traditional names of the streets around Saint Severin reflect the occupations of their inhabitants. The rue de la Parcheminerie which runs past Saint Severin, was also known at the rue des Ecrivains, while the rue Boutebrie, which intersects the rue de la Parcheminerie was traditionally called the rue aus Enlumineurs. Documentary evidence also reveals that the rue Neuve- Notre-Dame and the bridges over the Seine were also popular residences for manuscript makers. Standardization of book making practices also enabled the efficient coordination of specialists working in independent shops. A cursory examination of early fifteenth century Parisian manuscripts reveals a defined repertoire of decorative components including different initial types, painted and penned rinceaux, and elaborate and simple bar staffs. This standardization of decorative components was essential to maintain the integrity of the decorative plan and textual hierarchy of a manuscript, and it also made it possible for any trained specialist to carry out the decorative plan of a manuscript. All that would be needed would be brief written or oral instructions. Such instructions are perhaps echoed in accounts where the decorator is paid by the piece. For example, the accounts of the Confraternity of St. Jacques aux Pèlerins for 1485 contain the following record of payments to Jacques de Besançon for the decoration of a Gradual:

| to illuminate the newly made gradual, and he should have for the large letters which have staffs, knowing that the first has a staff along the length of the page top and bottom, the others along the length of the page, 11 sous -- to shape and flourish the large letters which will be azure and vermilion, 11 sous for each hundred -- and for 400 small flourished letters, 11 sous. And he received 17 gatherings on 22 June, 1485. |

The terms laid out in this

account would be clear enough for any trained craftsman to execute the ensemble

of the manuscript. The different types of initials to be used are specified,

and the plan of the border decoration, including the special decoration given

to the opening page, is defined. The account also provided for the parcelling

out of the work by gatherings. A closely knit workshop would not be needed;

the planner of a manuscript could depend on a pool of trained craftsmen working

in the surrounding neighborhood to carry out the commission.

Examination of the books

the A Master worked on and the contributions of our artisan to these books provide

valuable information about his status. The A Master was involved in three important

commissions for Jean de Berry: the Belles Heures, the presentation copy of the

new translation of Valerius Maximus, and a copy of Josephus. The duke or his

artistic advisors must have been aware of and appreciated the A Master's work.

Our decorator also worked on deluxe manuscripts, such as the Livre de la chasse

and the St. Maur Hours, which were made for other patrons . And though the decoration

of the London copy of the Canarien (Fig. 26) may be meager in comparison to

manuscripts such as the Belles Heures, this account of the French campaign in

the Canary Islands would have been of great interest to its original recipient,

the Duke of Burgundy.

Not only did the A Master

participate in important commissions, but he played an important role in the

decoration of these books. He decorated the opening portions of the Valerius

Maximus and Josephus manuscripts made for Jean de Berry, suggesting that he

was the principal decorator of these important volumes. The A Master's contributions

to the St. Maur Hours are probably the best indication of his status. Here he

worked not only on the ordinary text decoration but on the bifolia containing

the most important miniature pages in the manuscript. For example, except for

Sext, each page introducing the Hours of the Virgin as well as the openings

of the Penitential Psalms and the Office of the Dead was decorated by the A

Master. He was clearly at the top of the hierarchy of decorators for, though

other artisans were assigned a greater number of pages, the A Master was chosen

to decorate the most important openings.

All this suggests that the

A Master was no ordinary practitioner of the trade, but a highly respected craftsman

whose work was clearly sought after. It does not seem to have been accidental,

therefore, that this decorator should have been called upon to assist in the

decoration of the Belles Heures. Robinet d'Estampes' entry for the Belles Heures

in the Fourth Account of the collection of Jean de Berry noted that the duke

had the manuscript made by his craftsmen ("fait faire par ses ouvriers").

In light of this statement, the relationship of the A Master to the Duke of

Berry needs to be clarified. It is apparent from the extant manuscripts that

although the A Master worked frequently for Jean de Berry, he did not work exclusively

for the duke. Study of documents relating to the book industry helps to clarify

the relationship between the A Master and Jean de Berry. We find cases of craftsmen

who were associated with a member of the nobility but who were also active members

of the general book industry. In a letter dated 29 April, 1364, for example,

Jean Lavenant was characterized as "scriptor librorum regis" (scribe

of the king's books) and was later referred to in an entry in the Burgundian

accounts as "escripvain du roy et de mon seigneur" (scribe of the

king and my lord [Duke of Burgundy]). Other references to Lavenant in the same

accounts are less precise, and refer to him as simply "escripvain demourant

à Paris" (scribe living in Paris). Lavenant's involvement in the

general book trade is indicated by the appearance of his name among the libraires

in a document dated 1368. This case suggests that the A Master could have been

considered as one of the "ouvriers" of Jean de Berry while also remaining

an active member of the book industry. To be associated with such a distinguished

patron reflected the high status of a craftsman within a particular specialty.

Although it is not possible

to associate the A Master with any documented individual involved in the manuscript

industry, we can at least present a rough sketch of his career. His earliest

work appears in three Books of Hours textually related to Nantes: the Morgan

Hours (MS M. 515) (Fig. 12),

a Book of Hours formerly in the Dyson Perrins collection (Figs.

7 and 11) both of Nantes use, and the Keble College Hours, whose calendar

lists Nantes saints (Fig. 28). This suggests that the A Master's career began

in Nantes. While there, he possibly worked on the decoration of the Pontifical-Missal

made for Étienne Loypeau, the Bishop of Luçon (Fig. 13).

All four manuscripts date from the last decade of the fourteenth to the first

years of the fifteenth century.

The colophon of the Nantes

Hours in the Morgan library, written by the scribe of the manuscript, Ivo Luce,

fixes the date and origin of the volume: "L'an mil IIIIc et II furent escriptes

et enlumines cestes matines a la ville de Nantes" (These hours were written

and illuminated in the year 1402 in the city of Nantes). On the one hand this

colophon substantiates our conclusion that the A Master worked in Nantes, but

it also raises intriguing questions. The 1413 inventory of the Berry collection

states that the presentation copy of the new translation of Valerius Maximus

was sent to the duke on New Year's Day 1402 by Jacques Courau. Consequently

the Valerius Maximus manuscript must have been produced before the Morgan Hours.

Since there is every reason to believe that the Valerius Maximus was made in

Paris, the A Master must have left Nantes by 1401, in order to work on the Valerius

Maximus in Paris. Did he then return in 1402 to Nantes to decorate the Morgan

Hours?

Similar questions arise

about the relationship of the Morgan Hours colophon to the miniatures in the

manuscript, which have been attributed by Millard Meiss to a very innovative

artist of the beginning of the fifteenth century, called by Meiss the Coronation

Master. Meiss attributed to this hand the frontispiece of the Coronation of

the Virgin in a Légende dorée of 1402-1403 in Paris (Bibliothèque

nationale, MS fr. 242), miniatures in a Bible historiale in Paris (Bibliothèque

nationale, MS fr. 159) given to Jean de Berry in 1402, and illustrations of

the earliest copy of the French translation of Boccaccio's De claris mulieribus

(Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 12420), presented to Philippe

le Hardi by Jacques Rapondi on New Year's Day 1403. All of these books were

apparently produced in Paris. Did the Coronation Master, like possibly the A

Master, suspend an active career in Paris to travel to Nantes to work on the

Morgan Hours? Another possible explanation was suggested to me by François

Avril, who felt it unlikely that the miniatures of the Morgan Hours were painted

in Nantes. Avril considered it more probable that Ivo Luce or some other compatriot

from Nantes sent the manuscript to Paris for the painting of the miniatures.

Perhaps the A Master, newly established in Paris, might have served as the contact

between the Nantes and Paris book industries and have been given the responsibilities

of decorating and of overseeing the painting of the miniatures..

The A Master was undoubtedly

attracted to Paris by the rich potential for patronage in its flourishing manuscript

industry. By 1405, he decorated the London copy of Le Canarien (Fig. 27). By

the beginning of 1408 at the very latest, he appears to have been an established

craftsman in Paris, as indicated by the colophon of MS Douce 144. This was a

period of great productivity for our decorator. In 1408, he contributed not

only to the decoration of the Oxford book, but probably worked on the Paris

copy of the Livre de la chasse as well. During this same time, he was also involved

with the decoration of the Belles Heures, completed in 1408 or 1409. The deluxe

nature of these books suggests that the A Master had already acquired a significant

reputation. He may even have been able to employ an assistant for his work on

MS Douce 144 and the Livre de la chasse.

Shortly after completing

his part in the Belles Heures, the A Master probably began work on the St. Maur

Hours, convincingly dated circa 1411 by Meiss. His conclusion gains support

from the striking similarities between the decorative plans of the St. Maur

Hours and the Belles Heures. Major openings in both manuscripts employ an elaborate

staff along the sides and bottom of the text area with painted rinceaux filling

out the borders (cf. Figs. 8 and 9), while the text pages of both manuscripts

have a simple bar staff running along the sides and bottom of the text area

with penned rinceaux and gold leaves decorating the borders (cf. Figs. 1 and

29). Although the individual components are standard in Paris manuscript decoration

of the period, the decorative plan found in these manuscripts appears infrequently.

We have already established the A Master as the principal decorator of the St.

Maur Hours. Could he have been responsible also for defining the basic decorative

plan of this manuscript?

Appropriately, the latest

manuscript in which the work of the A Master has been found --the French translation

of Josephus (MS fr. 247)-- was left unfinished at the time of the death of our

decorator's most important patron, Jean de Berry. In this work, the A Master

was responsible for the decoration of the openings of the first four books.

His painted rinceaux were replaced in the openings of the remaining ten books

by penned rinceaux and acanthus sprays. It is unusual to find these two distinct

types of decoration used interchangably in the decoration of a manuscript. The

change in decorative plan undoubtedly corresponds to a break in the production

of the manuscript. Meiss defined three distinct stages in the production of

MS fr. 247. Clearly the work of the A Master belongs to the first campaign during

the lifetime of Jean de Berry. The acanthus decoration was probably executed

during the second stage about 1420 when the Master of the Harvard Hannibal painted

the frontispiece miniature, while the miniatures added by Jean Fouquet after

1476 represent the third and final stage.

This study has demonstrated

how important the examination of manuscript decoration can be in understanding

the workings of the Parisian manuscript industry. By defining the responsibilities

and the working relationships of the different specialists, we gain a better

picture of the creation of individual books and of the general structure of

the industry. The evidence suggests that book producers depended on the coordinated

activities of independent craftsmen. The frequent assumption that the various

stages in the production of a manuscript were carried out in a single workshop,

then, needs severe qualification. Like other medieval industries, the manuscript

industry demanded a clear articulation and standardization of the discrete specialties.

The success of a practitioner depended on the ability to conform to the standards

of the trade and to work effectively within a network of interdependent shops.

This study has also examined

the work of a type of craftsman whose contributions are frequently overlooked

in traditional art historical investigations. Art historians have certainly

been correct in analyzing the dramatic stylistic innovations in Parisian manuscripts

of the early fifteenth century. The work of miniaturists such as the Coronation

Master, the Boucicaut Master, and the Limbourg brothers was important in the

developing naturalism of early fifteenth century art, but it should not be evaluated

in isolation. Much of the splendor of the manuscripts in which these miniaturists

worked is due to the contributions of decorators like the A Master. Traditional

art historical assumptions that decorative work was left to less-gifted craftsmen

and to assistants need to be corrected. Certainly miniaturists such as the Limbourg

brothers gained the high admiration of their patrons, but we should not let

this overshadow the appreciation of patrons for decorators such as the A Master.

It should be recalled that the work of Christine de Pizan's Anastasia was "...highly

esteemed, no matter how rich or precious the book...." The articulation

of the book industry into discrete specializations makes assumptions of the

relative importance of miniaturists in comparison to the masters of "secondary

decoration" highly misleading. Comparing the work of miniaturists to that

of decorators is like comparing fullers and dyers in the cloth industry. All

the specialists are essential to the success of the final product. On the basis

of our study, therefore, the decision to call upon the A Master to contribute

to the decoration of a manuscript was by no means inconsequential. A patron

or planner of luxury manuscripts such as the Belles Heures or the St. Maur Hours

paid careful attention to the best available talent in each of the specialties

involved in the production of the book. We can imagine that the work of the

A Master, like that of Anastasia, was appreciated as standing out "...among

the ornamental borders of the great masters." Although the work of the

A Master appears in the margins, the contributions of decorators should play

a more central role in future discussions of medieval manuscript production.