Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 214 Assignments

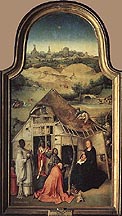

Bosch's Prado Epiphany

The altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi by Hieronymus Bosch in the Prado in Madrid has been appropriately called the Prado Epiphany. "Epiphany" as the manifestation of divinity is a central theme of the work. The work draws a contrast between the Magi as the first Gentiles to acknowledge Christ's divinity and the Jews who rejected Christ. The following table presents an interpretation of many of the different details of the painting. This makes clear that Bosch created his work for an audience that was well-versed in the Bible and familiar with orthodox Biblical interpretation.

|

Exterior: The Mass of St. Gregory: Golden Legend: A woman who sometimes offered bread in the church, as was the usage of the faithful, began one day to laugh when, at the consecration, Gregory uttered the words: 'May the Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ profit thy soul unto life everlasting!' At once the saint drew back the hand which was about to place the Host upon the woman's tongue, and set the sacred Host upon the altar. Then, before all the congregation, he asked the woman why she had dared to laugh. And the woman made answer: 'I laughed because you called this morsel of bread, which I kneaded with my own hands, the "Body of Christ."' Then Gregory prostrated himself and prayed to God for the woman's unbelief; and when he arose, he saw that the Host which lay upon the altar had changed into a piece of flesh in the form of a finger. He showed this flesh to the incredulous woman, who immediately came back to the faith. And again the saint prayed, and again the flesh took the form of bread; and Gregory gave it in Communion to the woman. The Mass of St. Gregory, thus, establishes the theme of acceptance and rejection of Christ as central to the meaning of the altarpiece. |

||

|

John 10: 1-10: Amen, amen I say to you: He that entereth not by the door into the sheepfold, but climbeth up another way, the same is a thief and a robber. 2But he that entereth in by the door is the shepherd of the sheep. 3 To him the porter openeth; and the sheep hear his voice: and he calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out. 4 And when he hath let out his own sheep, he goeth before them: and the sheep follow him, because they know his voice. 5 But a stranger they follow not, but fly from him, becaue they know not the voice of strangers. 6 This proverb Jesus spoke to them. But they understood not what he spoke to them. 7 Jesus therefore said to them again: Amen, amen I say to you, I am the door of the sheep. 8 All others, as many as have come, are thieves and robbers: and the sheep heard them not. 9 I am the door. By me, if any man enter in, he shall be saved: and he shall go in, and go out, and shall find pastures. 10 The thief cometh not, but for to steal, and to kill, and to destroy. I am come that they may have life, and may have it more abundantly.

|

|

|

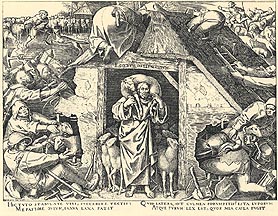

The theme of the Good Shepherd was used in Reformation pamphlets like this one. Here the "thieves" are identified with the clergy.

|

||

| Peter Bruegel, The Parable of the Good Shepherd, Philippe Galle engraver, 1561. | ||

|

Canticles 2: 9: Behold he standeth behind our wall, looking through the windows, looking through the lattices. For the use of this passage in images of the Adoration of the Shepherds see Robert Baldwin, "The Hidden God, the Inner Eye, and the Humble Style in Fifteenth-Century Netherlandish Art" available on his web-site under the category of unpublished talks. To quote the relevant passage from Baldwin's essay (pp. 3-4): "Since early patristic commentary, the wall was seen as the sinful flesh hiding Christ from human sight and separating fallen mankind from God. The window in turn was a window of spiritual sight through which God or the human soul looked, the latter seeing only a shadowy realm with its promise of a heavenly, face to face gazing without walls. Abbot Wolbero's commentary on Canticles 2:9 is typical:

|

||

|

|

||

|

Romans 11: 17: And if some of the branches be broken, and thou, being a wild olive, art ingrafted in them, and art made partaker of the root, and of the fatness of the olive tree, 18 Boast not against the branches. But if thou boast, thou bearest not the root, but the root thee. 19 Thou wilt say then: The branches were broken off, that I might be grafted in. 20 Well: because of unbelief they were broken off. But thou standest by faith: be not highminded, but fear/ |

|

|

John 10:11-14: I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd giveth his life for his sheep. 12 But the hireling, and he that is not the shepherd, whose own the sheep are not. seeth the wolf coming, and leaveth the sheep, and flieth: and the wolf catcheth, and scattereth the sheep: 13 And the hireling flieth, because he his a hireling: and he hath no care for the sheep. 14: I am the good shepherd; and I know mine, and mine know me. |

|

|

Isaiah 1:3: The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master's crib: but Israel hath not known me, and my people hath not understood. 4 Woe to the sinful nation, a people laden with iniquity, a wicked seed, ungracious children: they have blasphemed the Holy One of Israel, they are gone away backwards.

|

||

|

The virtually ubiquitous appearance of the ox and ass in images of the Adoration of the Magi is here distinguished by the notable absence of the oxen. Gregory the Great in his Moralia in Job (I, 16) glossed the Isaiah passage with the identification of the ox as a symbol of the Jews and the ass as a symbol of the gentiles: Finally, the ass stands for the simplicity of the pagan when the Lord is said to have ridden on the ass on his way into Jerusalem. To come to Jerusalem sitting on an ass is to possess the simple hearts of the pagans and by holding them and guiding them to lead them to the vision of peace.[113] A single, ready example suffices to show all this, for by the oxen the workers of Judea are meant and through the ass the pagan peoples: it is said through the prophet, "The ox knows his owner and the ass knows the corral of his master."[114] Who is the ox if not the Jewish people whose necks were bowed down by the yoke of the Law? And who is the ass if not the pagan, whom any rustler finds a brute animal without any sense and leads him astray where he will. The ox knows his owner and the ass recognizes the corral of his master, for the Hebrew people found the God whom they had worshipped but not known, while the pagans accepted the forage of the Law which they had not had. |

||

| Gift of the first magus represents the Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac. This story was one of primary Old Testament types for the Crucifixion of Christ, that comes to life in the altarpiece before which Gregory the Great prays on the exterior. | ||

|

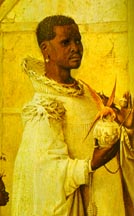

The collar worn by the second magus represents the Queen of Sheba presenting gifts to Solomon: 3Kings 10, 1-2: And the queen of Sheba, having heard of the fame of Solomon in the name of the Lord, came to try him with hard questions. 2 And entering into Jerusalem with a great train, and riches, and camels that carried spices, and an immense quantity of gold, and precious stones, she came to King Solomon, and spoke to him all that she had in her heart. The lower band of the collar apparently represents the sacrifice of the Paschal lamb and the story of Passover(Exodus 12). The inclusion of this scene reiterates the Eucharist imagery of the altarpiece, and also calls attention to the deliverance of the Israelites from Egypt. |

||

|

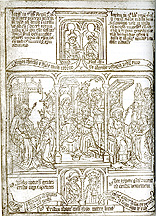

Image on the gift of the third king has been identified as Abner's homage to David in Hebron: 2 Kings 3, 19-21. Queen of Sheba presenting gifts to Solomon and Abner's homage to David both appear in the Biblia Pauperum associated typologically with the Adoration of the Magi (C). Queen of Sheba as a Gentile Queen is a type for the Magi. |

||

|

Biblia Pauperum page showing the Adoration of the Magi: Vs. 1: The multitude here typify the nations longing to be joined to Christ. Vs. 2: This typifies the Gentiles, to whom the coming of Christ was known. Vs. 3: Christ is adored; gold, frankincense and myrhh are laid before him. 2 Sam. iii. 10: It may be read in the second book of Kings (chap iii) that Abner, chief captain of the armies of Saul, came to David in Jerusalem, offering to subdue all the people of Israel to him which then followed the house of Saul. Which thing prefigures the coming of the Magi to Christ, who adored, offering mystic gifts. David: Ps. lxxii. 10: "The kings of Tharsis and the isles bringing gifts.' Isa. ii.2: "And all nations shall flow unto Him, and many people shall go up unto the Lord's house." 1 Kings x. 1:It may be read in the first book of Kings that the Queen of Sheba heard of the fame of Solomon, and came into Jerusalem with great gifts, in adoration for him; which queen was a Gentile; which will typify the Gentiles who came from afar to worship with gifts. Isa. lx. 14: And they shall worship Thy footsteps." Num. xxiv.17: There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a rod shall arise out of the root of Israel. |

||

|

Like the Rolin Madonna, the Virgin and Child are represented as the sedes sapientiae, or Throne of Wisdom. The oldest magus kneels before the Virgin in an attitude that is echoed by St. Gregory before the altar on the exterior of the altarpiece. Positioned prominently between the oldest magus and the figure of Christ is the gift of the second magus. The incense is placed on a plate that is identifiable as a paten, the Eucharistic plate used to hold the bread of the Eucharist. The magus thus looks through the Eucharistic paten to the infant Christ held on the lap of the Virgin. This reiterates the doctrine of transubstantion central to the story of the Mass of St. Gregory on the exterior. It is significant that the Bible does not refer to the three magi but to the three gifts: Matthew 2:11: "And entering into the house, they found the child with Mary his mother, and falling down they adored him; and opening their treasures, they offered him gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh." Biblical commentaries on this passage saw in these gifts different aspects of Christ. The most widely accepted reading is picked up in the entry for Epiphany in the Golden Legend: "...these three gifts signified the royalty, the divinity, and the humanity of Christ: because gold is used for royal tribute and He was the highest King, incense for divine worship, since He was God, and myrrh for the burial of the dead, since He was a mortal man." The special prominence that Bosch gives to the second gift calls attention to the magi's acknowledgment of the divinity of Christ. which is in stark contrast to the rejection of Christ's divinity by the Jews. The oldest Magus can see through the visible symbol of Christ to the divinity of Christ as the true wisdom. |

||

|

Above the keystone of the dilapidated building in the background of the left wing appears an upside down frog. On the adjacent jamb appears a robed figure holding a wand and gesturing to the frog. Frogs ring what is probably the crown of the second magus held by the mysterious, semi-nude figure standing in the doorway in the central panel. Frogs also decorate the cloth hanging between the legs of this figure. The first gift of the Magi with its representation of the story of Abraham and Isaac squashes a group of frogs. The appearance of these frogs is probably a reference to the Second Plague in Moses' competition with the magi of the Pharaoh (Exodus 8). The Plague of Frogs was the last of the Ten Plagues that the magi of the Pharaoh could perform. Biblical commentaries conventionally compared the meaningless croaking of frogs to the fables associated with the Old Testament magi who, like frogs, "can offer only tedium to the ears and not food to the mind [Pseudo-Augustine, "De Decem Plagis et Decem Praeceptis, Sermo XXXI, Patrologia Latina, 39, 1783-84]." The false wisdom of the Old Testament Magi is juxtaposed to the True Wisdom of Christ visualized in the painting by the representation of the Madonna and Child as the Sedes Sapientiae or the Throne of Wisdom. Much of the scholarly discussion about the painting has revolved around the identification of the enigmatic figure standing in the doorway. In an article published in the 1950s, Lotte Brand Philip made an identification still widely accepted of the figure as the Jewish Anti-Christ. As seen above in the details of the shepherds, there is certainly an anti-Semitic theme in the altarpiece, but it is unclear why if this figure is the anti-Christ he is so closely associated with the Magi, the Gentiles. This figure appears more linked to the Magi. This is suggested by identifying the object he holds in his hand as the crown of the second Magus. The similarity of the coloration of this object to the collar worn by the second magus and the absence of an identifiable crown for second magus support this identification. The most plausible identification (originally proposed by Charles Scillia and cited in Walter Gibson's discussion of the painting) seems to be the pagan sorcerer Balaam, who prophesized the coming of the star of Bethlehem when he was instructed by God to announce: "I shall see Him but not now: I shall behold Him but not nigh; there shall come a star out of Jacob and a scepter shall rise out of Israel (Numbers 24:17)." This text accompanies the typological scenes of the Adoration of the Magi in the Biblia Pauperum (C). The prophecy was integrated into the liturgy for Epiphany. Medieval commentaries saw Balaam as the precursor of the Magi. The legend of the Magi climbing a mountain to watch for the star predicted by Balaam was integrated into the Golden Legend.: Saint John Chrysostom gives another explanation of the coming of the Magi to Jerusalem. According to him, they were astrologers who, from generation to generation, spent three days every month upon a high mountain, waiting for the appearance of a star which Balaam had foretold to them. New Testament references (2 Peter 2:15; Jude 11: Revelation 2:14) to Balaam cast him in a very different light. Balaam is understood as a false prophet and a heretic: Leaving the right way they have gone astray, having followed the way of Balaam of Bosor, who loved the wages of iniquity, But had a check of his madness, the dumb beast used to yoke, which speaking with man's voice, forbade the folly of the prophet (2Peter 2:15-16). The second verse of the Peter passage refers to the story of Balaam and his ass (Numbers 22: 21-35). On the way to visit Balak, the king of Moab, in order to curse the Israelites, Balaam's path was blocked by an angel bearing a sword. The ass which Balaam was riding could see the angel while Balaam could not: And the ass seeing him [the angel], thrust herself close to the wall, and bruised the foot of the rider (Numbers 22:25). The ass goes on to speak the word of the Lord, and Balaam acknowledges his error and "Forwith the Lord opened the eyes of Balaam, and he saw the angel standing in the way with a drawn sword, and he worshipped him falling flat on the ground (Numbers 22:31)" This story presents an explanation for the wound encased in a reliquary on the figure's leg, and it also lends further support for the unusual prominence of the ass. Vision is again a major theme. Bosch by including Balaam is drawing a contrast between the Old Testament Gentiles who were blinded by their errors and the Magi who were lead to Christ. The Jews of the New Testament were blinded by their errors. Larry Silver in a recent article ("God in the Details: Bosch and Judgment(s)," Art Bulletin, 2001, 83, December issue) has called attention to the importance of sight and "right seeing" in works like Bosch's Prado Table Top.

|

||

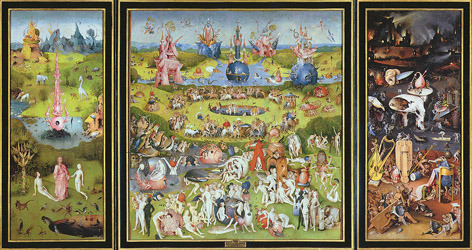

The Haywain Triptych (see Wikipedia ) |

Garden of Earthly Delights (see Wikipedia) |