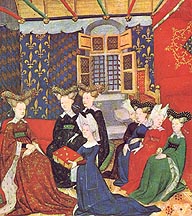

Between 1410 and 1415, Christine de Pizan

presented the Queen of France, Isabeau de Bavière, with

a lavishly illustrated copy of her collected works. [James Laidlaw has suggested that the manuscript was given to the Queen as an étrennes present in 1414.] This manuscript,

now in the British Library (Harley 4431), is introduced with a frequently reproduced

miniature showing Christine presenting this book to Isabeau in

the Queen's chamber. Art historians have long commented on the

naturalism of the image with its articulation of interior space

and the attention to detail. In a recent article, Sandra Hindman

has compared the carefully rendered details with documentary evidence.

From the physiogomy of Isabeau to the lavishly appointed chamber,

Hindman demonstrates that the miniature corresponds with the documentary

record, and claims that what she characterizes as the miniature's

"stylistic realism" "permits us to consider the

visual artifact as a legitimate historical document."

I can empathize with Hindman's desire

to try to break through the veil of conventions to find a legitimate

historical record of an actual event, but I feel Hindman's claim

that the miniature represents an historical event misses the point.

Her conclusion is based on the assumption that with more detailed

documentary research one can arrive at a truer picture of how

something really was. But as recent critical theory has shown,

the "reality" presented by modern historical research

is our construction as much as that of a past period. Rather than

trying to break through the veil of conventions, I would like

to reconsider this image from the perspective of the conventions.

By conventions, I mean the literary, social, and artistic practices

of her period. As recent studies have emphasized, a central issue

that Christine de Pizan faced was "to establish and to authorize

her new identity as a woman writer." In doing this, she had

to work within the literary practices and social conventions of

her own period. By exploring the image from the perspectives of

literary production and patronage as well as of court structure,

I will argue that Christine uses this image to define her position

and authority as a woman writer. Even the style of the miniature,

I will contend reflects Christine's search for an authority to

use in her debates with traditional authorities.

I will draw upon both the writings of

Christine and the images that illustrate them. Recent studies

of the manuscripts of Christine have demonstrated her direct involvement

in the production of these books. Gilbert Ouy and Christine Reno

have shown that Christine frequently acted as the copyist of her

texts. In fact, they have demonstrated that the London manuscript

is an autograph by Christine. Sandra Hindman has convincingly

shown that Christine planned the pictorial cycles for her texts.

Considering the importance of the commission, there is every reason

to expect that the miniaturist responsible for the presentation

miniature was following Christine's direction.

The details of Christine's biography are well known. This

is in marked contrast to the still prevalent rule of the anonymity of most medieval

writers. Christine inscribed her life into her texts: she is a frequent character

in her own texts, and she alludes to her personal experiences as integral parts

of her texts. This has been seen to be a reflection of Christine's awareness

of her unique position as a female writer. Christine, born in Venice in 1364,

was the daughter of Thomas de Pizan, a respected astrologer. While still a child

she left her native Italy with the rest of her family to join her father who

had taken a position as the astrologer and physician in the court of Charles

V. At the age of fifteen, she married Etienne Castel, a young nobleman who served

as a secretary in the royal chancery. With the deaths of her father and husband,

Christine's secure position was gone. Later in her Livre de la Mutacion de

fortune (The Book of the Change of Fortune), she was to describe her situation

as being adrift on a ship during a storm. With the loss of her husband, she

had to take the helm. Here she has appropriated a dominant patriarchal metaphor

for the role of the husband in the family and the king in the state. Christine

resisted the usual solutions to her predicament of remarriage or entry into

a convent. Instead she began her career as a writer. Her early works were largely

in the courtly tradition of love poetry, but by the early years of the fifteenth

century she began to focus on more historical and moral topics.

The problems faced by Christine in establishing her position

as a writer are made apparent by examining the clerkly tradition, the dominant

literary discourse of the later fourteenth and early fifteenth century in France.

Clerkly discourse was associated with the traditional intellectual institutions

of the period --Cathedral schools, monastic orders, the urban universities,

and the governmental bureaucracies. Mastering a tradition of authoritative texts

and the facility to refashion these authorities in contemporary contexts were

essential elements of clerkly discourse. Employing Classical and Christian authorities,

"clercs" devoted themselves to writing moral, philosophical, theological,

historical, and political texts. This tradition based in male institutions and

employing Latin, the patriarchal language, apparently left little space for

a female voice.

Reviewing what is probably her most famous prose text,

the Livre de la Cité des Dames, or the Book of the City of

Ladies, we can see how Christine refashions the clerkly tradition to define

a space for her distinctively female voice. The text opens with the following

passage:

"One day as I was sitting alone in my study surrounded

by books on all kinds of subjects, devoting myself to literary studies, my usual

habit, my mind dwelt at length on the weighty opinions of various authors whom

I had studied for a long time."

From the outset, she places herself in the space of the clerc surrounded by the authoritative texts. Slightly later, however, she allows this solitary space of contemplation to be disrupted by the daily, domestic routine: "I had not been reading for very long when my good mother called me to refresh myself with some supper, for it was evening." Could you imagine Thomas Aquinas allowing his scholarly pursuits to be disrupted by what he would consider as such mundane matters, let alone record them in a major text? This tension between the worlds of scholarly study and of daily experience becomes a central theme in the book.

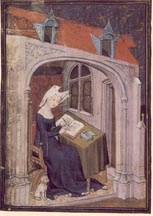

Miniatures introducing this text reveal

the same duality. In this miniature from the London manuscript that introduces Christine's Cent balades (f. 4r) ,

a fifteenth-century viewer would not miss the borrowings from

traditional author portraits, but the placement of the dog at

her feet again disrupts the traditional formula.

Amidst her scholarly pursuits, Christine

comes across an explicitly misogynist text written by Mathéolus.

This causes Christine to reflect on the authoritative tradition.

She finds in her study of "the treatises of all philosophers

and poets and from all the orators..." that "they all

concur in one conclusion: that the behavior of women is inclined

to and full of every vice." Although she is aware that the

opinions of the authorities contradict what she knows to be "the

natural behavior and character of women," Christine bemoans

her fate at being born a woman. "So occupied with these painful

thoughts, my head bowed in shame, my eyes filled with tears, leaning

on the pommel of my chair's armrest, I suddenly saw a ray of light

on my lap...." This marks the appearance of the three virtues

who are going to lead Christine out of her state of despair and

help her to construct/write her city/book of ladies. This pairing

of city and book serves to reinforce Christine's appropriation

of traditionally male defined spaces. It is significant to note

that Christine's pose with her "head bowed in shame...leaning

on the pommel of [her] chair's armrest" again adopts a traditional

pose associated with male authority. I am referring here to the

tradition of contemplative, male figures extending from Antiquity

through Rodin's Thinker. It is also hard to miss the "pregnant"

reference to the Annunciation with the appearance of the three

virtues being marked by a "ray of light on [Christine's]

lap."

Appropriating traditional scholastic methodology,

Lady Reason reminds Christine to be aware of the contradictions

between the authorities, and Lady Reason presents Christine with

another authority to counter the bookish tradition of male authority

and that is "experience:" "Although you have seen

such things in writing, you have not seen them with your eyes."

In her earlier Epistre Othéa (The Letter of Othéa),

Christine had already called into question the authority of the

clerkly authorities due to their lack of worldly experience. All

they could do was to draw on the authority of their scripted sources.

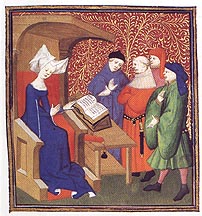

In the miniature above from the London manuscript which introduces her Proverbes moraulx (f. 259v) , Christine appropriates the conventions of clerkly authority. She places herself seated in a cathedra, the formal seat associated with ecclesiastical and intellectual authority during the Middle Ages. Her clerkly authority is bolstered by the presence of the book before her as she engages in a disputa or debate, with the men before her. The disputa was the dominant form of academic discourse in the medieval university. The dress of the men she debates with identify them as representatives of university and courtly authority.

It is important to bear in mind the balance

Christine attempts to achieve between traditional formulas and

natural details in her opening to the Book of the City of Ladies

when we consider the style of the London presentation miniature.

The inclusion of details like her mother calling her to supper

create a sense of authenticity to her account because we sense

that they are based on the authority of experience, and allows

Christine to create a space for herself within the clerkly tradition.

Comparably the balance between traditional formulas of presentation

images and specific details in the London frontispiece establishes

the authenticity and authority of this image.

It was not enough for Christine to establish

a space for herself within the literary traditions of her period,

but she also needed to articulate a space for herself within the

social practices of her period. Here we need to consider the dominant

role patronage played in the social life of the period. One's

position in the social life of the period depended on patronage

relationships. An individual's status and even identity depended

on whom one was connected to in this system.  Patronage reflected

the period's conception of reality. This is well illustrated by

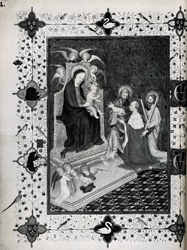

a miniature from the Brussels Hours (Brussels, Bibl. Royale, ms. 11060-1,p. 14) made for Jean de Berry. Here

we see Jean accompanied by his patron saints, St. John the Baptist

and St. Andrew, who present Jean to the Virgin and Child. Jean's

position in the heavenly court is directly related to the authority

of his patron saints. The hierarchy of the heavenly realm was

reflected in the marked distinctions in social rank in the terrestrial

realm. In relationships between different social classes, a person

of lower social standing depended on having patrons or advocates

in the upper social class to appeal their cause, just as Jean

de Berry depends on his patron saints in his appeal to the heavenly

court. In prayers addressed to the Virgin or Christ, one would

characterize oneself as "familia tua," or your servant

, just as any member of a household would characterize themselves

as a "familia."

Patronage reflected

the period's conception of reality. This is well illustrated by

a miniature from the Brussels Hours (Brussels, Bibl. Royale, ms. 11060-1,p. 14) made for Jean de Berry. Here

we see Jean accompanied by his patron saints, St. John the Baptist

and St. Andrew, who present Jean to the Virgin and Child. Jean's

position in the heavenly court is directly related to the authority

of his patron saints. The hierarchy of the heavenly realm was

reflected in the marked distinctions in social rank in the terrestrial

realm. In relationships between different social classes, a person

of lower social standing depended on having patrons or advocates

in the upper social class to appeal their cause, just as Jean

de Berry depends on his patron saints in his appeal to the heavenly

court. In prayers addressed to the Virgin or Christ, one would

characterize oneself as "familia tua," or your servant

, just as any member of a household would characterize themselves

as a "familia."

It can not be emphasized enough the central

role patronage played in literary and artistic production of the

period. To publish a text during this period meant the presentation

of a copy to a patron. The text could be a direct commission of

a patron, or the author could prepare a copy to present to a patron

in hopes for appropriate reward. The success or failure of a text

did not depend on its scholarly or literary merits as much as

the disposition of the patron. We should be aware of the reciprocal

relationship between author, text, and patron. The importance

of the author and of the text were tied to the relative status

of the patron. Likewise, it was an honor and enhanced the magnificence

of a patron to be presented a text by a respected writer. The

decision to whom to dedicate a text was, therefore, critical for

a medieval author. This concern is reflected in the letter in

which Boccaccio dedicates his De Claris Mulieribus (Concerning

Famous Women) to Madonna Andrea Acciaioli: "I have been turning

over in my mind to whom I should first send it, that it might

not languish in idleness on my hands, and that aided by another's

favor it might more safely go forth to the public.... To you,

therefore, I send, and to your name I dedicate, what I have so

far written concerning famous women.... Finally, if you shall

think fitting to give it courage to go forth to the public, sent

out under your auspices it will go free, as I think, from the

insults of the malicious." Undoubtedly many medieval texts

suffered the same fate as Martin Le Franc's poem, Le Champion

des dames (The Champion of Ladies). Le Franc had taken care

to prepare a lavish copy of his text, and presented it to the

noted bibliophile, Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, only

to find his manuscript used as a footstool for Philip's courtiers.

Authors could not make a living solely

from their writings. They generally depended on having a position

with the royal administration or within a noble household or being

attached to an educational institution. For example, Eustache

Deschamps, an important poet of the period, throughout his long

career held a number of positions within royal and ducal households.

For a number of years, he held the post of huissier d'armes

under Charles V and VI. This office required that he attend the

king when he arose and retired, and assist him when he mounted

his horse. He later served under Louis the Duke of Orléans

as maître d'hôtel (master of the household)

which entailed the supervision of the wine-cellar, pantry, kitchen,

and saucery. To us, these positions might seem trivial and beneath

the position of such an esteemed writer as Deschamps, but they

afforded him high status since they entailed close and even intimate

relationships with some of the most important patrons of the period.

These household positions were undoubtedly important signs of

the high regard his patrons had for Deschamps' literary accomplishments.

As a woman, Christine was excluded from

the positions within the royal administration and ducal households

occupied by her male colleagues. She was never a client in the

sense that she received a salary and protection from a lord for

the non-literary services she rendered. Whereas notable writers

like Guillaume de Machaut, Jean Froissart, and Eustache Deschamps

could pursue their writing as an avocation to supplement their

incomes, Christine wrote to live. She can thus be claimed to be

the first professional author. To understand how she supported

herself, we need to examine how she operated within the traditional

system of patronage.

She wrote texts both on commission and on speculation. For example, we know that Christine was commissioned by Philippe le Hardi, the Duke of Burgundy, to write a biography of his brother Charles V. She includes in this biography the following account of her receiving this commission:

| To my great pleasure it was told and reported to me by Monbertaut, the treasurer of the said Duke, that it would please him if I would compile a treatise on a certain subject.... I, therefore, moved with desire to fufill his wishes as far as my modest abilities allowed, travelled with my household to Paris, where he was at the time, at the Louvre; and there he, informed of my arrival, condescended to call me before him.... Having arrived in his presence, after the appropriate greeting, I told him the reason I had come and the wish I had to serve his highness to please him, as far as I was worthy, provided that I might be informed by him of the nature of the treatise on which it pleased him I should work. Then he, after condescending to thank me more fully than my unworthiness deserved, graciously told and declared to me the approach and the subject it pleased him I should adopt; and, after many fine proposals received from his grace, I took my leave with this pleasant commission. |

To receive such a commission from such an important patron

as the Duke of Burgundy was undoubtedly a great honor for Christine. Working

under a direct commission also provided her with financial security. The expression

"arrived in his presence" draws attention to the major goal of any

person at court, to gain direct access to the presence of the patron. The subservient

tone of this passage is unmistakable, and it has been cited by scholars as reflecting

the type of control a patron could have over the creation of a text. But I think

we should be careful not to overstate this control. Just as Christine's protestations

of her "unworthiness" should be understood in the context of the commonplace

of affected modesty traditional in medieval texts, so to I think Christine's

references to the explicitness of Philip's command reflect formulas of flattery.

We will see later in this paper an example of how this type of flattery of a

patron's wisdom and literary abilities was given visual form in frontispiece

decoration.

A large number of Christine's works were produced on speculation. Producing texts on speculation entailed financial risk. It was not simply the amount of time taken in writing the text, but Christine like any other author producing a text on speculation had to take care to prepare a deluxe copy of the text appropriate for presentation. Authors were well aware that patrons were very conscious of the external trappings of a manuscript. For example, when Jean Froissart decided to present Richard II of England a copy of his collected poetry he paid special attention to the preparation of a deluxe copy which he describes as being: "finely ornamented, bound in velvet, and decorated with silver-gilt clasps and studs." Although the making of such a book entailed a considerable financial outlay, Froissart states: "I spared no pains, and the cost and labor seem trifling." In the following passage from her Livre des trois vertus (Book of the Three Virtues), Christine expresses similar concerns about producing a text on speculation:

| ...I thought I would multiply this work throughout the world in various copies, whatever the cost might be, and present it in particular places to queens, princesses, and noble ladies. Through their efforts, it will be honoured and praised, as is fitting, and better circulated among other women. I already have started this process; so that this book will be examined, read, and published in all countries. As it is in the French tongue and as that language is more common throughout the world than any other, this work will not remain useless and forgotten. It will endure in many copies all over the world without falling into disuse, and many valiant ladies and women of authority will see and hear it now and in time to come. |

Following this Christine presents a not so thinly veiled

appeal for appropriate compensation and for future patronage: "May they

pray to God for their servant Christine, desiring that they may see her life

in this world last as long as their own. May it please them all to remember

her kindly with friendly greetings as long as she lives." Entries in royal

and ducal accounts attest to Christine's success in receiving appropriate rewards.

It should be noted that these rewards were not always monetary. In some cases

Christine was presented with pieces of metalwork or jewelry. To us this might

seem odd, but it conformed to the practice of the period. In need of liquid

assets, members of the aristocracy regularly pawned their metalwork and jewelry,

and even their books. I think this decision to reward Christine with such luxury

objects also reflects this period's conception of an author and his or her product.

Writers frequently referred to themselves as "faiseurs" or "ouvriers,"

or makers or craftsmen. For example, Eustache Deschamps eulogized Guillaume

de Machaut as: "Noble poete et faiseur renommé," or "noble

poet and renowned maker." Christine described her own development as a

writer in terms of a craftsman: "Thus like a 'ouvrier' who becomes more

and more subtle with frequent practice, continually studying diverse matters...,

my style gained much greater subtly and much higher content." Inventory

records frequently identify her books as "fait par Christine," or

"made by Christine." Such references may allude to Christine's direct

involvement as scribe and supervisor, but I think they also suggest how this

period understood an author's work in much more of a material sense than we

do. Froissart, for example, as quoted above, describes in detail the binding

of the manuscript he presented to Richard II but says little about its literary

contents. Any superficial examination of manuscripts from this period reveals

products of fine craftsmanship. It would thus be highly appropriate to reward

an author in kind by giving them an object of comparable craftsmanship to their

work.

As suggested by the passage from the Book

of the Three Virtues, Christine, in some cases, did not present

a copy of a new text to a single patron but rather presented it

to multiple patrons. For example, Christine dedicated her (Letter

of Othéa) to no fewer than four different patrons: the

Dukes of Orleans, Berry, and Burgundy, and to probably Henry IV,

king of England. She prepared separate dedications for each of

these patrons, and as has been shown recently by a study of the

extant original copies, she adapted the pictorial contents to

the special interests of the individual patron.

Another opportunity for patronage open

to Christine was to present a volume of her collected works to

a patron. This was a practice employed by her predecessors Guillaume

de Machaut and Jean Froissart. In his Voir dit, Machaut

refers to a book in which are copies of all the works that he

had ever written. In another passage, he says that he is having

a copy of this book made for one of his lords. The table of contents

of one of the best collected manuscripts of Machaut's works begins:

"This is the arrangement which Guillaume de Machaut wished

to have in his book. A rubric in a copy of the poetical works

of Froissart suggests that they were arranged by their author

in a similar way: "in this book are several works on love

and morality which were written, made, and ordered by the venerable

and honorable Jean Froissart." We also, of course, have the

precedent of the collected works which Froissart presented to

Richard II mentioned above.

Considering such eminent precedents, we

can conclude that the preparation of copies of her collected works

was a statement for Christine of her high status and accomplishments

as a writer. We have evidence of at least four copies of her collected

works. A now fragmentary copy was apparently intended for the

Duke of Burgundy. Another copy was apparently originally intended

for Louis d'Orléans, but after his murder, this copy was

subsequently given to Jean de Berry. The London manuscript, as

documented by its dedicatory

poem, was explicitly commissioned by Isabeau de Baviere.

We have, thus, seen how Christine fashioned

a place for herself within the literary traditions and social

practices of her time. We can now return to an examination of

the London presentation miniature. Here, we need to again consider

how Christine operated within, adapted, and refashioned contemporary

conventions. Presentation miniatures like author portraits were

standard trappings of a medieval book. We could trace a tradition

of presentation images back to antiquity, but for our purposes,

we can examine a particular group of images that I will label

as chamber presentation images. We can see this iconography being

developed under the patronage of Charles V and continued during

the reign of Charles VI.

An early example of a chamber presentation image I have been able to identify is the famous frontispiece to a Bible historiale (historical Bible) now in The Hague. The miniature shows Jean Vaudetar presenting the book to Charles V. Significantly absent in this image are the formal trappings of royalty. In their place we see Charles wearing a cap, or béguin, and the vestments with cowl and lapels associated with the scholarly authority of a university professor. This shift in iconography was clearly a part of the conscious construction of Charles V as "le sage," or the wise. Also striking in this miniature is the great degree of specificity in the rendering of Charles V. In this and a number of other presentation images in books made for Charles V, scholars have detected a greater informality. For example, the presentation miniature for the new French translation of Aristotle's Ethics, Politics, and Economics shows Nicole Oresme, the translator, presenting the text to Charles V who is comparably dressed to the Bible frontispiece.

The curtain and figure peeking around it denote an informal setting. A similar informal setting is suggested by the presentation image for Le Songe du verger.

Here the youthful Charles VI as Dauphin appears to the right and a number of courtiers peer around a curtain on the left. In each of these miniatures, the King's space is articulated by a cone shaped canopy over his head, and as observed by one of my students, note how the individual presenting a book is allowed to enter the King's space.

That these miniatures share a number of these informal elements

suggests a programmatic intention. I am not comfortable with seeing

this shift in iconography as simply reflecting the increasing

naturalism of the art of the period as has traditionally been

argued. I would like to suggest that this shift should be seen

in relationship to a significant restructuring of the royal household

that took place during the fourteenth century. This period witnessed

the development of the royal chamber as the center of power in

the ever expanding royal household. The chamber provided the king

with an inner sanctum where the king could conduct his business

surrounded by his most intimate companions. Appointment to a position

within the King's chamber was one of the highest prizes in the

patronage system. Writing about the Burgundian court in the fifteenth

century, Olivier de la Marche says: "In the prince's chamber,

the chief pensionary or the (first) gentleman of the chamber must

attend to putting the Prince's nightcap on his head; and the more

intimate the service for the prince, the greater the honour."

Access to the king's ear made chamber servants important intermediaries

for petitioners from all levels of society seeking royal privileges.

This function provided a lucrative supplemental income to a chamber

servant's annual pension.

Returning to the Charles V presentation images, it is significant that Jean Vaudetar and Nicole Oresme were members of the royal household. Undoubtedly, Jean Vaudetar commissioned the Bible as a gift to Charles V to symbolize his personal loyalty to the King. Oresme undoubtedly appreciated his position in the household of Charles V as a sign of his status as one of the most important intellectuals of the period. It is at first sight paradoxical that these images would appear during a period when the public image of the king was becoming increasingly formalized, but the informality of these presentation images intentionally serves to underscore the elite status of these individuals. This intimacy with the king was only possible to the limited group of people who had access to the king's chamber. We should again be aware of the reciprocal aspects of these relationships. Charles V undoubtedly appreciated the membership of such distinguished administrators and intellectuals in his household as symbols of its magnificence. As the power of the king became increasingly veiled in royal splendor, these informal images took on a greater potency enhancing both the authority of the king and the elite members of his household.

Jean Froissart's account in his Chronicles of the presentation of his

book of poetry to Richard II illustrates quite well the importance of the king's

chamber well. When he arrived in England, Froissart made a special effort to

befriend men attached to Richard's chamber, and it was through their intercession

that he was granted an audience with the king. He writes:

|

On the Sunday, the whole council were gone to London, excepting the duke of York, whom remained with the king, and sir Richard Sturry: these two, in conjunction with sir Thomas Percy, mentioned me again to the king, who desired to see the book I had brought for him. I presented it to him in his chamber, for I had it with me, and laid it on his bed. He opened and looked into it with much pleasure. He ought to have been pleased, for it was handsomely written and illuminated, and bound in crimson velvet, with ten silver-gilt studs, and roses of the same in the middle, with two large clasps of silver-gilt, richly worked with roses in the center. The king asked me what the book treated of: I replied, "Of Love!" He was pleased with the answer, and dipped into several place, reading parts aloud, for he read and spoke French perfectly well, and then gave it to one of his knights, called sir Richard Credon, to carry to his oratory, and made me many acknowledgments for it. |

I think we should not take Froissart's precise identification of the individuals

and of the context as the king's bed chamber simply as evidence of accurate

reportage. Like the meticulous attention to detail shown in Christine's frontispiece,

Froissart's reference to placing the book on the king's bed is to authenticate

where the presentation took place. Froissart's enumeration of these details

was intended to reflect his honor and status to be granted the privilege to

make this presentation in such an important place and with a number of the most

august members of the English royal court as witnesses. Richard II told Froissart

to consider himself "as of the royal household of England."

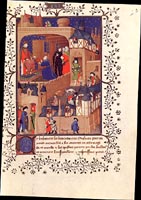

Pierre Salmon, an advisor and ambassador to Charles VI, develops further this iconography of the King's chamber in books he wrote on the explicit commission of the King. In one of these miniatures we are presented with a marvelous overview of the royal palace.

On one level we should admire the naturalism and spatial complexity of this miniature, but it also illustrates the important privilege of having direct access to the king. This is made more explicit by the appearance of the two doorkeepers protecting the access to the King. We can imagine that the two figures speaking with the doorkeeper at the bottom are disgruntled petitioners who are being denied access to the palace let alone the King's chamber. The usher with mace standing by the upper door is the formal guardian to direct access to the king. It should also be observed that we can not only identify the portrait of Charles VI, but one of the witnesses standing behind Salmon can be easily identified as Jean de Berry, the uncle of Charles VI. His presence further amplifies the importance of this presentation.

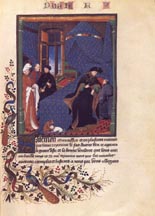

In a later version of this same text, Salmon has included a miniature

showing the bed chamber of Charles VI. Here Charles VI speaks

with Salmon on the right hand side of the miniature, while Jean

sans Peur, the Duke of Burgundy, and Jean de Berry look on. It

should be noted that this is not actually a presentation image

proper, but it shows Charles VI explaining the details of the

commission to Salmon. Like Christine's account of Philippe le

Hardi's commission for the biography of Charles V discussed earlier,

emphasis is placed on the authority and wisdom of the patron and

the subservient role of the author to follow the command. The

formulaic aspect of this iconography should be emphasized. This

is especially apparent when we recall the historical record of

the unstable political climate of the reign of Charles VI. Suffering

from repeated bouts of madness caused by schizophrenia, Charles

VI's reign was marked by the continual rivalry of the Dukes for

political control. Jean sans Peur openly admitted that he was

responsible for the assasination in 1407 of his principal rival

Louis, Duke of Orleans, the brother of Charles VI. The inclusion

of Jean sans Peur and Jean de Berry as well as the commanding

gesture of Charles VI strategically asserts the ideology of effective

royal authority eventhough we know it to be more illusion than

fact.

Undoubtedly Christine de Pizan drew upon this developing iconography of chamber presentation images in constructing the frontispiece for the London manuscript. Like her eminent predecessors, Christine was clearly aware of the honor of making a presentation in the Queen's chamber. Although excluded by birth and gender from holding a formal position within the household of the queen, she could at least be considered an honorary member like the privilege granted to Froissart by Richard II.

Our frontispiece thus visually asserts Christine's eminent literary

authority, but as we have noted in other examples, we should be

aware of the reciprocal aspect of the relationship witnessed here.

Clearly it was an honor for Isabeau to have Christine specially

prepare a copy of her collected works for her, and literary patronage

under the Valois was a symbol of its magnificence of this dynasty.

I would also like to suggest that Christine might also have been

making reference to the contemporary political situation in setting

this miniature in the Queen's chamber, unmistakably identifiable

by the profuse armorial display. Christine was clearly aware of

the important role Isabeau played as Queen and protector of the

future of the Valois dynasty in the troubled political climate

of the reign of Charles VI. As early as 1402, Isabeau was granted

absolute power to rule during the repeated episodes of Charles'

mental illness. In 1405, Christine, herself, addressed a letter

to the Queen in which Christine appealed to Isabeau to make peace

among her family members, praying in particular for the reconciliation

between the Dukes of Orleans and Burgundy (the brother and cousin

of the king respectively).

In this context it is interesting to read the dedicatory poem or Prologue adreçant à la royne that introduces the Harley manuscript. The fourth line reads: "Le corps enclin vers vous m'adresce". The word corps is rich in this context. It can be understood to refer to Christine kneeling before the Queen; it can also be understood to refer to this edition of texts or corpus which was designed especially for the Queen; or it can also be understood to refer to the idea of France as the "body politic" which is looking to Isabeau in this period of turmoil.

Considering this political situation,

I would suggest that Christine intentionally chose to set this

presentation image in the context of the Queen's chamber to articulate

an alternative and distinctly female center of political authority.

Comparably the Queen's chamber presents an alternative focus of

literary patronage.

Another nagging political problem confronting

the royal family was the repeated calls for financial reform necessitated

by the immoderate royal household expenditures. The household

of the queen was singled out in particular as in need of reform.

The rumored scandalous behavior of members of her court also drew

public attention. Fifteen ladies-in-waiting attached to her court

were later arrested for improper behavior. Without explicitly

mentioning Isabeau or her court, Christine, in her The Book

of the Three Virtues, discussed the appropriate conduct of

a queen and her household. Christine emphasizes the need for chastity,

sobriety, and prudence in order to maintain the good public reputation

of the queen and her court. In this context, the London frontispiece

with its clear distinctions in placement and dress of the various

participants could almost act as an illustration for a chapter

in Christine's Book of the Three Virtues entitled: "How the

wise princess will keep the women of her court in good order."