As a way of introducing our discussion of Northern Renaissance art, I want to consider the image above. It is a miniature in a type of prayer book known as a Book of Hours. Especially in the early part of this course, many of the major monuments we will be considering will be this type of book. The book of hours developed as a distinct form in the latter part of the thirteenth century, and became extremely popular during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Modelled on the Breviary used by members of the religious orders and clergy in their daily cycle of prayers, the Book of Hours was made primarily for members of the laity and their private devotion. Although there are conventional contents of the Book of Hours, each Book of Hours is unique with components added to reflect the specific needs of the original or subsequent owners of the book. This individuality of content and the emphasis on private devotion reflects an important religious and ideological shift that occurs during this period towards a greater emphasis on individuality.

This particular Book of Hours has long believed to have been made for Mary of Burgundy (1457-1482; r. 1477) the daughter and only child of Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy (1433-1477, r.1467-1477 ). She was born into a family, the Valois, that traced its ancestry back to the French monarchs of the later fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Mary's marriage to Maximilian of Austria marked an important consolidation of power integrating the rich domains of Burgundy in the Netherlands and central France with the Hapsburg-Spanish line of Austria and Spain. More recently scholars have suggested that the book was made for Margaret of York, the third wife of Charles the Bold and Mary's stepmother.

This specific image shows Mary in her own private chamber attending to her private devotion. In her lap appears a book whose opening letter "O" clearly identifies it as a Book of Hours since two of the most popular prayers to the Virgin begin with the letter "O": Obsecro te and O intemerata. The gold edges and cloth used to protect the book from direct hand contact suggests the preciousness of the book as an object. A fourteenth century poem by Eustache Deschamps is useful to compare to the Mary of Burgundy image:

An Hours of the Virgin must be mine

As it should belong to a woman

Coming from noble peerage

Which are of subtle work

Of gold and of blue, rich and elegant

Well ordered and well appointed,

Well covered with fine, gold cloth;

And when it will be open,

Two clasps of gold which will close it

That anyone who will see it

Can say and assess by it all

That one could not carry one more beautiful.

(Eustache Deschamps, Oeuvres, IX, pp. 44-46 (quoted in De Winter, Philippe le hardi, p. 328):

Heures me fault de Nostre Dame

Si comme il appartient a fame

Venue de noble paraige

Qui soient de soutil ouvraige

D'or et d'azur, riches et cointes,

Bien ordonnées et bien pointes,

De fin drap d'or tresbien couvertes;

Et quant elle seront ouvertes,

Deux fermaulx d'or qui fermeront

Qu'adonques ceuls qui les verront

Puissent par tout dire et compter

Qu'on ne puet plus belle

porter)

A Book of Hours was not just a symbol of religious piety, but was also a clear indication of status. Notice how in the syntax of Deschamps' poem the patron's noble status (noble paraige) is paralleled to the work's fine craftsmanship (soutil ouvraige). The poem places a heavy emphasis on the richness and elegance of the book: "Of gold and of blue, rich and elegant." "Richness" was a very important attribute in this court culture of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It is not just a coincidence that one of the major monuments of this first part of this course is the Très riches heures of John of Berry. We need to distinguish our conception of "richness" from this culture's conception. We judge richness in our culture on the basis of monetary wealth, but as an examination of the accounts of noble households reveals, richness was not based during this period on the basis of accumulation of money. Frequently aristocratic households depended on loans from bourgeois merchants and bankers to subsidize their lifestyles. Rather this court culture can be characterized as a display culture which means that power and status is reflected in the material display of possessions. Great attention was paid in aristocratic households to the "magnificence" of the dress of its members. Members of a court were regularly compensated by a salary and provided with clothing appropriate to their status in the court. We should understand how the richness of the decoration of a book like the Hours of Mary of Burgundy was a direct reflection of the power and the status of the owner.

This miniature of Mary of Burgundy reflects well one of the major visual aspects of art of this period. Traditional studies of the art of the Northern Renaissance place a major emphasis on this period's break from the more abstract styles of the earlier Middle Ages to the increasing emphasis on naturalism. Clearly the artist of this miniature has learned the techniques for rendering space and light in art. The window in the miniature appears to present us with a perfect visual example of the Renaissance conception of a painting as a window onto a world. The light in the miniature not only articulates the solidity of the figures but also renders their physical properties. The artist differentiates the way light reflects off of or is absorbed by different materials. Note details like the transparency of the glass.

This seems to us a tour-de-force of the observation of the material world. We can appreciate the almost botanical accuracy of a detail like the purple iris or carnation.

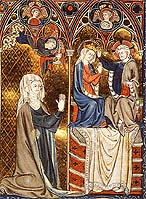

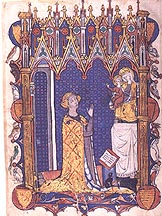

We should not see this naturalism of the miniature as an end in itself, but we need to understand this culture's conception of reality and the function of this miniature within the Book of Hours. The miniature can be seen as a reflection of this culture's conception of prayer and the relationship between the physical and spiritual worlds. In prayer, one learns to go through the text or image that one is contemplating to the spiritual reality that lies beyond. The text and religious image were understood as aids in this spiritual movement. In the following illustration, Yolande de Soissons is shown kneeling at her prie dieu on which is placed a devotional text. On an altar appears a statue of the Madonna and Child:

Psalter Hours of Yolande de Soissons, French, Amiens, c. 1280-90 (New York, Morgan, MS M.729, fol. 232v)

In contemplating the image of the Madonna and Child, Yolande is spiritually imagining herself in front of Mary and the infant Christ. The sculpture appears to come to life, even the dog looks up attentively.

An

early fourteenth century French manuscripts illustrates the different stages

of

An

early fourteenth century French manuscripts illustrates the different stages

of mystical vision. In the first scene a Dominican nun is being instructed by her

confessor. This is followed by an image of the nun praying before an image of

the Coronation of the Virgin, one of the popular subjects of devotional images

in the later Middle Ages. This scene represent corporeal vision. The ultimate

goal of mystical contemplation is presented by the image at the lower right.

Here the same nun looks up at an image of the Throne of Mercy, another popular

devotional image, but instead of a physical statue, the enthroned God the Father,

Crucified Christ, and Dove of the Holy Spirit hover above the altar. The transcendent

nature of this vision is signified by cloud form around the Trinity. The nun

has gone through the corporeal devotional statue to its heavenly prototype.

mystical vision. In the first scene a Dominican nun is being instructed by her

confessor. This is followed by an image of the nun praying before an image of

the Coronation of the Virgin, one of the popular subjects of devotional images

in the later Middle Ages. This scene represent corporeal vision. The ultimate

goal of mystical contemplation is presented by the image at the lower right.

Here the same nun looks up at an image of the Throne of Mercy, another popular

devotional image, but instead of a physical statue, the enthroned God the Father,

Crucified Christ, and Dove of the Holy Spirit hover above the altar. The transcendent

nature of this vision is signified by cloud form around the Trinity. The nun

has gone through the corporeal devotional statue to its heavenly prototype.

After she became the Duchess of Burgundy in 1468 when she married Charles the Bold, Margaret of York commissioned several devotional and moral treatises. Her almoner, Nicolas Finet wrote a text entitled Dialogue de la duchesse de Bourgogne à Jésus Christ. Margaret's copy now in the British Library (Add 7970) is introduced with a miniature of Margaret experiencing an apparition of the resurrected Christ in her bed chamber. The object of Margaret's devotion has become physically present in her own bed chamber.

After she became the Duchess of Burgundy in 1468 when she married Charles the Bold, Margaret of York commissioned several devotional and moral treatises. Her almoner, Nicolas Finet wrote a text entitled Dialogue de la duchesse de Bourgogne à Jésus Christ. Margaret's copy now in the British Library (Add 7970) is introduced with a miniature of Margaret experiencing an apparition of the resurrected Christ in her bed chamber. The object of Margaret's devotion has become physically present in her own bed chamber.

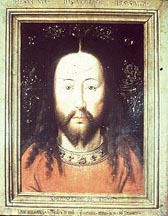

A similar point  is

is

made

by two miniatures from the early sixteenth century Hours of King James

of Scotland. On the left, James is shown in prayer before an altarpiece

of Christ as the Salvator Mundi (or saviour of the world), like the

one on the left associated with the style of Jan Van Eyck. In another

miniature Queen Margaret is shown praying before an altar on which

stands

a sculptural

group

of the

Annunciation.

Above

appears

a vision of the Virgin and Child with a crescent moon. This is a standard

iconographical convention for representing the Virgin and Child, the Madonna

of the Crescent

Moon. This is the Apocalyptic

Woman described in the first verse of the 12th chapter of the Book of Revelation:

"And a great sign appeared in heaven: A woman clothed with the sun, and

the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars." An

example of this formula can be

made

by two miniatures from the early sixteenth century Hours of King James

of Scotland. On the left, James is shown in prayer before an altarpiece

of Christ as the Salvator Mundi (or saviour of the world), like the

one on the left associated with the style of Jan Van Eyck. In another

miniature Queen Margaret is shown praying before an altar on which

stands

a sculptural

group

of the

Annunciation.

Above

appears

a vision of the Virgin and Child with a crescent moon. This is a standard

iconographical convention for representing the Virgin and Child, the Madonna

of the Crescent

Moon. This is the Apocalyptic

Woman described in the first verse of the 12th chapter of the Book of Revelation:

"And a great sign appeared in heaven: A woman clothed with the sun, and

the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars." An

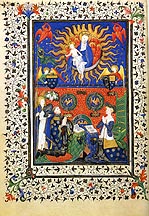

example of this formula can be found

in the Boucicaut Hours, one of

the major monuments of early fifteenth century, Parisian manuscript illumination.

This miniature shows the the Virgin as the Apocalyptic Woman above while

below are seen Marshall Boucicaut and his wife in prayer. Significantly the

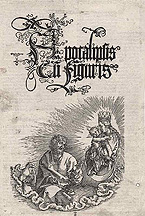

Boucicaut miniature merges the physical with the spiritual. Albrecht Dürer

in 1511 created a new frontispiece for his Apocalypse series showing Saint

John

before the Apocalyptic Woman. Returning to the miniature of Margaret of Scotland

in prayer, close examination of her angle of vision suggests that her physical

vision is directed to the Annunciation group which leads her to the spiritual

vision

of the Virgin

as

the Apocalyptic

Woman. Thus she goes through the physical to the spiritual.

found

in the Boucicaut Hours, one of

the major monuments of early fifteenth century, Parisian manuscript illumination.

This miniature shows the the Virgin as the Apocalyptic Woman above while

below are seen Marshall Boucicaut and his wife in prayer. Significantly the

Boucicaut miniature merges the physical with the spiritual. Albrecht Dürer

in 1511 created a new frontispiece for his Apocalypse series showing Saint

John

before the Apocalyptic Woman. Returning to the miniature of Margaret of Scotland

in prayer, close examination of her angle of vision suggests that her physical

vision is directed to the Annunciation group which leads her to the spiritual

vision

of the Virgin

as

the Apocalyptic

Woman. Thus she goes through the physical to the spiritual.

Comparably in the Mary of Burgundy image, the aim of Mary's devotion is realized in the image of the church through the window:

Here we see Mary again in prayer before the Virgin and Child. Any student of Medieval art can clearly identify the characteristics of Gothic architecture in this building. But closer inspection reveals a detail that suggests that this is not a church in our physical realm but one that exists in the spiritual realm. The light in this church is clearly coming in from the left hand side. Considering that it was a rule in Medieval architecture to "orient" churches so that the altar is placed at the east end of the building, the light in this miniature is coming from the north, a physical impossibility in the northern hemisphere. The same detail is shown in a painting entitled The Madonna in the Church by Jan Van Eyck:

As scholars have shown, the light here is clearly a spiritual light, a symbol of Christ, the True Light. An original frame now lost for this painting included a lengthy inscription derived from a popular hymn associated with the feast of the Nativity. This hymn ends with the lines: "As the sunbeam through the glass passes but not stains, so the Virgin, as she was, a virgin still remains." It should be remembered that during the Middle Ages the Church was understood as a symbol of the Virgin, "Ecclesia." Christ spiritually enters the Church like He entered the womb of the Virgin, entering but not breaking. This symbolism is reinforced in the miniature by placing the Vigin and Child directly in front of the altar of the sanctuary. In medieval symbolism the lap of the Virgin was seen as an altar upon which is placed Christ in the form of the host of the Eucharist. This image makes visible the spiritual reality or anagogical meaning of the Eucharist. In receiving the host in celebrating the Mass the faithful imagine themselves before Christ in the Heavenly Church.

In contemplating this image, we are asked, therefore, to go through the material forms to the spiritual reality beyond. The objects in the foreground can be seen as symbols of spiritual realities. For example in both the Yolande de Soissons and Mary of Burgundy images, the owners are accompanied by dogs:

Certainly dogs were frequent pets in aristocratic households, but as anyone who has studied Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Wedding Portrait with its prominent dog in the center foreground, the dog amongst other meanings was a symbol of faith, explaining the popular canine name "Fido," the Latin word for faith:

Flowers were a frequent symbol of spiritual realities. One of the most frequent was the iris:

The ancient name for the iris was gladiolus, or "sword-lily." As such, the lily alludes to a traditional representation of Mary after the Passion, her heart transfixed by a sword, here illustrated by a miniature of the Crucifixion from the so-called Gotha Missal dating from about 1375:

The sword here relates to the statement

made by the priest Simeon during the Presentation of the infant

Christ into the temple: "Yea, a  sword shall pierce through

thy soul also [Luke 2:35]." The sword and lily regularly appear flanking the head of Christ in images of the Last Judgment such as Albrecht Dürer's. The lily on the left is associated with the mercy shown to the elect while the sword on the right is associated with the judgment of the damned. The lily is regularly held by the Angel Gabriel in images of the Annunciation like that in the Trés riches heures.

sword shall pierce through

thy soul also [Luke 2:35]." The sword and lily regularly appear flanking the head of Christ in images of the Last Judgment such as Albrecht Dürer's. The lily on the left is associated with the mercy shown to the elect while the sword on the right is associated with the judgment of the damned. The lily is regularly held by the Angel Gabriel in images of the Annunciation like that in the Trés riches heures. Carnations were a symbols of

betrothal which suggests the possibility that the book was made

for Mary's marriage to Maximilian in 1477. In Christian thought the Virgin was

understood as the Bride of Christ, her son. The

glass

holding

the

iris, following the interpretation of the windows above, could

also be a symbol for Mary's virginity.

Carnations were a symbols of

betrothal which suggests the possibility that the book was made

for Mary's marriage to Maximilian in 1477. In Christian thought the Virgin was

understood as the Bride of Christ, her son. The

glass

holding

the

iris, following the interpretation of the windows above, could

also be a symbol for Mary's virginity.

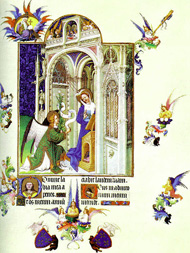

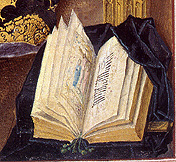

The

page above also from the Hours of Mary of Burgundy

The

page above also from the Hours of Mary of Burgundy  places

the miniature of Christ Nailed to the Cross into a devotional context.

Unlike the other page, Mary of Burgundy is not represented here. Instead we

the viewer take on her role as we contemplate the image. The Book of Hours at

the lower right is opened to what is probably the Hours of the Passion. A string

of pearl and gold prayer beads lie on the pillow. These beads refer to one of

the most popular devotional practices in Catholicism, the saying of the Rosary.

According to the Roman Breviary: "The Rosary is a certain form of prayer

wherein we say fifteen decades or tens of Hail Marys with an Our Father between

each ten, while at each of these fifteen decades we recall successively in pious

meditation one of the mysteries of our Redemption." The pearl beads mark

off the decades of the Hail Marys while the gold beads correspond to the Paternosters

or Our Fathers. The chain has at one end a small cross and at the other end

appears a gold ball or the final Paternoster bead.

places

the miniature of Christ Nailed to the Cross into a devotional context.

Unlike the other page, Mary of Burgundy is not represented here. Instead we

the viewer take on her role as we contemplate the image. The Book of Hours at

the lower right is opened to what is probably the Hours of the Passion. A string

of pearl and gold prayer beads lie on the pillow. These beads refer to one of

the most popular devotional practices in Catholicism, the saying of the Rosary.

According to the Roman Breviary: "The Rosary is a certain form of prayer

wherein we say fifteen decades or tens of Hail Marys with an Our Father between

each ten, while at each of these fifteen decades we recall successively in pious

meditation one of the mysteries of our Redemption." The pearl beads mark

off the decades of the Hail Marys while the gold beads correspond to the Paternosters

or Our Fathers. The chain has at one end a small cross and at the other end

appears a gold ball or the final Paternoster bead. The boxwood Paternoster or prayer-nut on the left comes from the southern

Netherlands about 1500. It shows on the left an image of the Crucifixion. The

quantity of detail crammed into the bead which measures a little over an 1 1/2"

in diameter is a clear demonstration of the love of miniaturization in the art

of the period. The artist makes visible the pain of Christ and the thieves and

the sorrow of the Virgin who swoons at the base of the Cross. On the right hand

half of the bead is shown a representation of the Mass of St. Gregory. This

recounts how one day while celebrating the Mass, a woman doubted the true presence

of Christ in the elements of the Eucharist. Her belief is restored when Pope

Gregory the Great shows her how the bread of the Eucharist had been transformed

into the flesh of Christ. This subject was particularly popular in the art of

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was a visual demonstration of the

doctrine of Transubstantiation, which contends that the bread and wine become

transformed into the body and blood of Christ. The popularity of the story can

also be explained by understanding how it also demonstrates the importance of

the religious image. Just as bread and wine are transformed into the body and

blood, so in contemplation what is represented in the religious images becomes

present in the inner eye of the faithful. An example of this is presented by

a woodcut by

The boxwood Paternoster or prayer-nut on the left comes from the southern

Netherlands about 1500. It shows on the left an image of the Crucifixion. The

quantity of detail crammed into the bead which measures a little over an 1 1/2"

in diameter is a clear demonstration of the love of miniaturization in the art

of the period. The artist makes visible the pain of Christ and the thieves and

the sorrow of the Virgin who swoons at the base of the Cross. On the right hand

half of the bead is shown a representation of the Mass of St. Gregory. This

recounts how one day while celebrating the Mass, a woman doubted the true presence

of Christ in the elements of the Eucharist. Her belief is restored when Pope

Gregory the Great shows her how the bread of the Eucharist had been transformed

into the flesh of Christ. This subject was particularly popular in the art of

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was a visual demonstration of the

doctrine of Transubstantiation, which contends that the bread and wine become

transformed into the body and blood of Christ. The popularity of the story can

also be explained by understanding how it also demonstrates the importance of

the religious image. Just as bread and wine are transformed into the body and

blood, so in contemplation what is represented in the religious images becomes

present in the inner eye of the faithful. An example of this is presented by

a woodcut by  Albrecht

Dürer, dated 1511, of the Mass of St. Gregory. The divisions between physical

and spiritual reality have been broken down. Christ as the Man of Sorrows surrounded

by the instruments of His Passion appears powerfully alive. The altar cross

has become the wood of the True Cross, and the altar table has become the sepulchrum

domini (or the sepulcher of Christ). Significantly except for Gregory the

Great and the Angels above, we are the only ones who see the True Presence of

Christ. We, in effect, become the sceptical Roman matron who becomes convinced

by the miraculous presence of Christ. The attention of the deacon assisting

Gregory at the altar is directed to the sacrament on the altar, acolytes on

the right attend to a thurible, while Cardinals and Bishops in the background

are apparently oblivious to the mystery occuring before them. The group is dominated

by the physical symbols of ecclesiastical authority including the Papal crown

and the bishop's crozier. Dürer in this print visualizes what Gregory the

Great himself articulates in his Dialogues: "...what right believing

Christian can doubt that in the very hour of the sacrifice, at the words of

the Priest, the heavens opened, and the quires of Angels are present in that

mystery of Jesus Christ; that high things are accomplished with low, and earthly

joined to heavenly, and that one thing is made of visible and invisible...."

Dürer demonstrates to the viewer how true contemplation leads to a realm

where the physical and spiritual are miraculously present.

Albrecht

Dürer, dated 1511, of the Mass of St. Gregory. The divisions between physical

and spiritual reality have been broken down. Christ as the Man of Sorrows surrounded

by the instruments of His Passion appears powerfully alive. The altar cross

has become the wood of the True Cross, and the altar table has become the sepulchrum

domini (or the sepulcher of Christ). Significantly except for Gregory the

Great and the Angels above, we are the only ones who see the True Presence of

Christ. We, in effect, become the sceptical Roman matron who becomes convinced

by the miraculous presence of Christ. The attention of the deacon assisting

Gregory at the altar is directed to the sacrament on the altar, acolytes on

the right attend to a thurible, while Cardinals and Bishops in the background

are apparently oblivious to the mystery occuring before them. The group is dominated

by the physical symbols of ecclesiastical authority including the Papal crown

and the bishop's crozier. Dürer in this print visualizes what Gregory the

Great himself articulates in his Dialogues: "...what right believing

Christian can doubt that in the very hour of the sacrifice, at the words of

the Priest, the heavens opened, and the quires of Angels are present in that

mystery of Jesus Christ; that high things are accomplished with low, and earthly

joined to heavenly, and that one thing is made of visible and invisible...."

Dürer demonstrates to the viewer how true contemplation leads to a realm

where the physical and spiritual are miraculously present.

The

window is

enframed by jamb sculptures that represent two

Old

Testament

stories:  Abraham's

Abraham's  Sacrifice

of Isaac on the left and Moses Raising the Brazen Serpent on the right.

To explain the inclusion of these two scenes we must have an understanding

of Biblical interpretation in the Middle Ages. A central issue for even

Jesus and his immediate followers especially Peter and Paul was the relationship

of Christ's ministry to the Jewish tradition and its scriptures. The events

of Christ's life were understood to fulfill Old Testament prophesy. The

Old Testament was understood not just as an account

of events before the time of Christ, but the events of the Old Testament were

seen to "prefigure" or typologically connect to events of the

New Testament. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), one of the Four Church

Fathers, in his City of God (XVI. 26) states that "the New

Testament is hidden in the Old; the Old is clarified by the New." Christ

himself articulates this relationship when he speaks of his coming Crucifixion:

"as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert so must the Son of man be

lifted up (John 3:14)." Christ also compares Jonah's three days spent in

the belly of the sea monster to the three days

he would

spend

in the tomb awaiting Resurrection (Matt. 12:40).

Sacrifice

of Isaac on the left and Moses Raising the Brazen Serpent on the right.

To explain the inclusion of these two scenes we must have an understanding

of Biblical interpretation in the Middle Ages. A central issue for even

Jesus and his immediate followers especially Peter and Paul was the relationship

of Christ's ministry to the Jewish tradition and its scriptures. The events

of Christ's life were understood to fulfill Old Testament prophesy. The

Old Testament was understood not just as an account

of events before the time of Christ, but the events of the Old Testament were

seen to "prefigure" or typologically connect to events of the

New Testament. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), one of the Four Church

Fathers, in his City of God (XVI. 26) states that "the New

Testament is hidden in the Old; the Old is clarified by the New." Christ

himself articulates this relationship when he speaks of his coming Crucifixion:

"as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert so must the Son of man be

lifted up (John 3:14)." Christ also compares Jonah's three days spent in

the belly of the sea monster to the three days

he would

spend

in the tomb awaiting Resurrection (Matt. 12:40).

Since Early Christianity, Biblical interpretation played an integral role in religious experience. Any Christian would have been aware of the echoes between the Old and New Testaments. Sermons, liturgical references in the Mass and Divine Offices, hymns, devotional literature, and the visual arts would all expose the Christian to this pattern of prefigurations. Belief in the relationships between the Old and New Testaments were central to the understanding of a universal Christian plan of history. The story of Abraham being given a test of his faith by God who asked him to sacrifice his only son Isaac was one of the most frequently cited prefigurations for Christ's Crucifixion. Both stories speak of the willingness of a father to sacrifice his only son for faith. The story of the Brazen Serpent (Numbers 21: 5-9) recounts how the Israelites, feeling lost in the wilderness, had turned away from Moses and God. In punishment the Lord sent fiery serpents. Repenting, the Israelites asked Moses to save them. The Lord instructed Moses to make a brazen or bronze serpent and to hang it from a tree, so that whoever looked upon it would be saved from the serpents. The lifting of the brazen serpent was understood to be a prefiguration of Christ being lifted on the Cross. Just as the brazen serpent saves the Israelites, Christ's sacrifice on the Cross will lead to Christian Salvation and remedying Original Sin that was brought on Adam and Even in the Garden through the temptation of the devil in the guise of a serpent.

In the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance, one of the most popular religious texts was the so-called Biblia Pauperum, or "Bible of the Poor" [also see the Catholic Encyclopedia article].Printed versions of this text, like the one illustrated above from about 1460, were widely available. The principal structure of the book is the narrative of the life of Christ. Each episode in the life of Christ is paired with two Old Testament scenes that were understood to be prefigurations for the New Testament story. The Old Testament scenes that are associated with the Crucifixion are Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac and Moses Raising the Brazen Serpent. Old Testament prophesies are also included with the inclusion of two prophet figures above and below the New Testament scene. That the designer of the Mary of Burgundy page consulted the Biblia Pauperum in laying out this page is suggested by the specific wording of the account of the Sacrifice of Isaac included in the Biblia Pauperum:

| We read in Gen. xxii. that when Abraham had stretched forth his hand to slay his son, the angel of the Lord from heaven prevented him, saying, "Stretch not forth thine hand against the child." Abraham signifies the Heavenly Father, who sacrificed His Son, to wit, Christ, for us all, on the Cross, that thus He might show us a sign of His fatherly love. |

The emphasis on the stretched hand of Abraham in this passage presents a clear parallel to the arms of Christ being stretched on the Cross in the scene through the window.

The

Old Testament scenes on the jambs of the window lead us to the scene of Nailing

of Christ to the Cross. Significantly one of the women

in the foreground dressed in court fashion seemingly is aware of our presence

and looks back at us and thus reinforcing the immediacy of this vision. The

goal of this type of meditation is to enter into the passion of Christ, to

feel compassion for the pain Christ suffered and for the sorrow of the Virgin

witnessing the death of her son. We are confronted by a complexity of time

and space: the Old Testament time alluded

to in the

jamb

figures,

the

time of Christ's Passion that appears immediately present outside the

window, and the time and space of the princess's private oratory in a late

fifteenth

century palace all are mixed in the image. What connects them is the

reality of religious devotion. In reciting the text of the Hours of the

Passion,

in contemplating the image of the Crucifixion in the Book of Hours,

in concentrating her prayers with the prayer beads, Mary of Burgundy would

imagine herself as being present at the Crucifixion. Devotional texts

like the late

fourteenth

century Life

of Our Blessed Saviour Jesus Christ call upon the worshipper to

empathetically imagine the different details of the Crucifixion, to

imagine the physical

pain Christ

suffered and the sorrow of Mary and the other followers:

The

Old Testament scenes on the jambs of the window lead us to the scene of Nailing

of Christ to the Cross. Significantly one of the women

in the foreground dressed in court fashion seemingly is aware of our presence

and looks back at us and thus reinforcing the immediacy of this vision. The

goal of this type of meditation is to enter into the passion of Christ, to

feel compassion for the pain Christ suffered and for the sorrow of the Virgin

witnessing the death of her son. We are confronted by a complexity of time

and space: the Old Testament time alluded

to in the

jamb

figures,

the

time of Christ's Passion that appears immediately present outside the

window, and the time and space of the princess's private oratory in a late

fifteenth

century palace all are mixed in the image. What connects them is the

reality of religious devotion. In reciting the text of the Hours of the

Passion,

in contemplating the image of the Crucifixion in the Book of Hours,

in concentrating her prayers with the prayer beads, Mary of Burgundy would

imagine herself as being present at the Crucifixion. Devotional texts

like the late

fourteenth

century Life

of Our Blessed Saviour Jesus Christ call upon the worshipper to

empathetically imagine the different details of the Crucifixion, to

imagine the physical

pain Christ

suffered and the sorrow of Mary and the other followers:

In discussing these pages from the Hours of Mary of Burgundy, I have put a good deal of emphasis on details and their symbolic interpretation. This has been intentional. It echoes the contemplative practice of the later Middle Ages. This is well illustrated by popular devotional images like an English woodcut from about 1500 which shows at the center the Man of Sorrows:

The objects that enframe the central figure bring to mind particular moments in Christ's Passion. In the spirit of devotional tracts like Life of Our Blessed Saviour Jesus Christ, the focus on the specific details helps to visualise and then meditate on the pain and humiliation Christ suffered during the Passion. The details begin with the Chalice and host reminding us of the Last Supper and goes on to represent details associated with Christ's Betrayal (lantern, 30 pieces of silver, and clubs & swords), Peter's Denial (rooster), Judgments before the High Priest and Pontius Pilate (heads of Priest and Pilate), Mocking (soldier), Flagellation (scourge and column), Way to Calvary (Veronica's Veil), Crucifixion (hammer, nails, dice, spear, stick with vinegar, and Pelican in its Piety), Deposition (ladder and pincers), and Resurrection (jars with spices and ointments brought to the tomb by the women on Easter morning). It is significant that the objects are not placed in a chronological order following the narrative. This makes the viewer of the image focus more on each object and its part in the Passion. The text, which was probably crossed out by a Protestant, can still be read. It states that anyone who says five Our Father, five Hail Marys, and recites the Creed while contemplating the image will be given an Indulgence of 32,755 years.

Philip the Good at Mass

A

miniature in a treatise on the Lord's Prayer demonstrates again the importance

of texts, images, and liturgy in directing the faithful to the spiritual

reality.

A

miniature in a treatise on the Lord's Prayer demonstrates again the importance

of texts, images, and liturgy in directing the faithful to the spiritual

reality. Mary

of Burgundy's grandfather, Philip the Good, is shown in a tent which has

been specially erected beside the high altar of a church. Philip is kneeling

at a prie-dieu with an open Book of Hours or prayer book before him. The

words Patre nostre in gold make it clear that the Duke is saying

the Lord's Prayer. His eyes are directed to a diptych showing on the left

panel an image of the Madonna and Child while on the right wing appears a

kneeling figure. This is undoubtedly the Duke himself. As in the Mary of

Burgundy image, Philip is directed by both the text and image to the goal

of his devotion which is to imagine praying before Virgin and Child in heaven.

Mary

of Burgundy's grandfather, Philip the Good, is shown in a tent which has

been specially erected beside the high altar of a church. Philip is kneeling

at a prie-dieu with an open Book of Hours or prayer book before him. The

words Patre nostre in gold make it clear that the Duke is saying

the Lord's Prayer. His eyes are directed to a diptych showing on the left

panel an image of the Madonna and Child while on the right wing appears a

kneeling figure. This is undoubtedly the Duke himself. As in the Mary of

Burgundy image, Philip is directed by both the text and image to the goal

of his devotion which is to imagine praying before Virgin and Child in heaven.

This miniature illustrates the different contexts of religious practice of the period. While attending to his private devotion, Philip's angle of vision also ties him to the priest standing at the altar and the public liturgical celebration. The priest prays before the Eucharistic elements. A gold sculptured altarpiece shows episodes of Christ's passion: Carrying the Cross on the left, the Crucifixion in the center, and the Descent from the Cross on the right. This altarpiece reminds us of the nature of the Eucharist as a commemoration of Christ's sacrifice on the Cross: the bread and wine of the Eucharist become the body and blood of Christ.

A fifteenth century observer would have been much more attuned to the magnificence and splendor of this image. The miniaturist has been very meticulous in emphasizing the richness of the fabrics, especially note the priest's blue chasuble decorated with gold and red embroidery and the Duke's black velvet houppelande lined with fur. The walls of the sanctuary are decorated with red silks again embroidered with gold decorations. The tent enclosing the Duke is again blue and embroidered in gold with the ducal devices of flint and firesteel. The candlesticks and chalice on the altar are clearly gold. It is significant to note that the sculptured altarpiece is gold. The richness of the furnishings of this chapel can be compared to the objects associated with the chapel of Philip the Bold, the grandfather of Philip the Good. These include a gold cross worth 900 francs composed of a crucifix set on a base of enameled silver with representation of the Nativity. There were also four gold angels holding depictions of the Virgin, apostles, and "Jews." Philip acquired in 1395 for 1,708 francs a statuette of St. Michael in gilded silver, placed on a silver pedestal; and a gilded silver cross on which were represented "a compassionate god," a Virgin, St. John, the four Evangelists, and some angels. There was also a gilded silver statue of the Virgin holding a Christ child in her arm. The Virgin was seated on a base decorated with enamel and her coat of arms. This figure was embellished with pearls and encrusted with ivory. The extraordinary richness of the objects included in the collection strikes the reader. Many of these objects were decorated with the Duke's coat of arms. The attention given to the richness of the ducal chapel reflects the intersection of politics and piety.

While many have assumed the diptych in front of the duke is a painting, Belozerskaya (p. 134), acknowledging the Burgundian preference for goldwork, considers it more likely that the diptych is an enameled gold piece. Painted after 1457, this miniature post-dates the great innovations of Netherlandish painting. We might expect a reference to works by Jan van Eyck who was Philip the Good's court painter, but this reflects our own biases. None of the great works of Jan van Eyck that have come down to us were painted for the duke. As inventories suggest, the duke's collection and taste focused primarily on fine tapestries, rich metalwork, and exquisite jewels.

A common denominator of the duke's taste was his interest in rich and costly materials. The Duke was very attentive to the political role of magnificent material display. The miniaturist leaves little doubt as whose space this is. As observed above the duke's tent is decorated with his devices while the ducal arms appear on the carpet before the altar. To the modern observer there seems to be a contradiction between the material display here and Christian piety.

The choir singing from a gradual or hymn book for the celebration of the Mass also documents a ducal interest that frequently gets overlooked in art historical discussions. The duke was very interested in sacred polyphony. His chapel choir was known as the envy of Europe. That princes were aware of the importance of music in enhancing a ruler's reputation is documented by the following quotation from the writings of Johannes Tinctoris, a Netherlandish composer actove at the court of the king of Napes:

| [T]he most Christian princes...desiring to enhance the divine service, founded chapels after the manner of David to which, at enormous expense, they appointed various singers to sing joyous and comely praise in different (but not conflicting) voices to our God. And since royal singers, if their princes are endowed with that generosity which brings men fame, are rewarded with honor, glory, and wealth, many are kindled with a passionate zeal for study of this kind.... [as quoted in Belozerskaya, Rethinking the Renaissance, p. 133] |

All of this suggests a very different conception of reality during the fifteenth century than our own. True reality was understood to be the spiritual realm, and that the physical reality of our day to day existence should be understood to be a symbol for this divine realm. All of the material forms are signs that are to lead us to God. St. Augustine, in his influential De Doctrina Christiana ("On Christian Doctrine"), wrote:

| [I]n this mortal life, wandering from God, if we wish to return to our native country where we can be blessed we should use this world and not enjoy it, so that the "invisible things" of God "being understood by the things that are made" may be seen, that is, os that by means of corporal and temporal things we may comprehend the eternal and spiritual. |

Bibliography:

Marina, Belozerskaya, Rethinking the Renaissance: Burgundian Arts across Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Illuminating the Renaissance, pp. 137-141, no. 137

For an example of a late fifteenth century Book of Hours to give a sense of the typical structure see the web pages dedicated to a Book of Hours in the Frick Fine Arts Library at the University of Pittsburgh.

For the Bibli Pauperum see Avril Henry, Biblia Pauperum: a Facsimile and Edition, Cornell University, 1987.

Hours of Mary of Burgundy: the Mass of the Blessed Mary