Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 214 Assignments

The Work of Jan van Eyck and Religious Vision

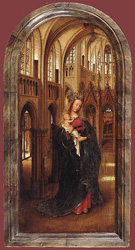

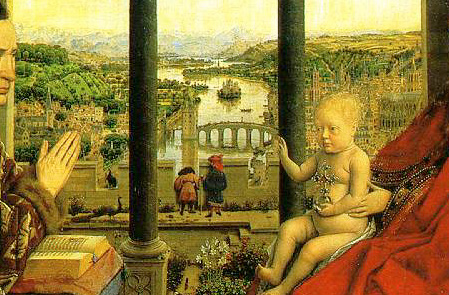

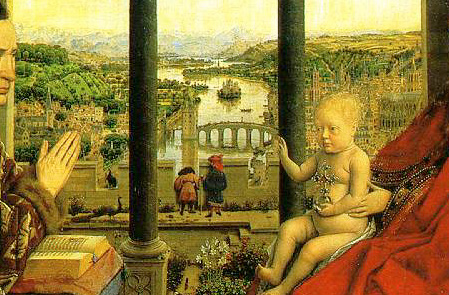

Jan van Eyck's mastery in the representation of space and light along with his meticulous attention to detail have challenged scholars to attempt to identify the details included in his paintings. For example, the details of the church included in the Berlin Madonna in the Church are so precise that scholars have tried to relate this to particular known structures. Van Eyck has very obviously studied Gothic architecture enough to introduce a contrast in design between the clerestory and triforium in the nave and in the transept. Despite the best efforts of scholars no convincing identification has been made. Comparably the cities in the background of the Rolin Madonna have defied identification. What becomes evident in these attempts is a difference between our and van Eyck's conceptions of reality. Where we tend to want to base our reality in immediate and direct experience, van Eyck sought to use experience and references to our immediate world as a means to what he would consider his true reality which transcends immediate experience. Van Eyck's conception of reality can be seen to be based on the tradition of medieval theology. St. Augustine in his On Christian Doctrine (I, iv) will state:

| Thus in this mortal life, wandering from God, if we wish to return to our native country where we can be blessed we should use this world and not enjoy it, so that the "invisible things" of God "being understood by the things that are made" may be seen, that is, so that by means of corporal and temporal things we may comprehend the eternal and spiritual." |

Following Neo-Platonic thought Augustine asks us to use the experience of the world as a means to attain eternal and spiritual truth. As a homo viator (wandering man), one should place their attention on attaining their true home. While drawing upon his experience of the world, van Eyck uses this as a means to represent his vision of spiritual reality. This is well illustrated by the two cities in the background of the Rolin Madonna:

St. Augustine writes in his City of God:

| Two loves have created these two cities, namely self-love to the extent of despising God, the earthly; love of God to the extent of despising one's self, the heavenly city. The former glories in itself, the latter in God. For the former seeks the glory of men while to the latter God as the testimony of the conscience is the greatest glory. The former lifts its head in self-glory, the latter says to its God: 'Thou art my glory, and the lifter up of my head' (Psalm, iii,4). The former dominated by the lust of sovereignty boasts of its princes or of the nations which it may bring under subjection; in the latter men serve one another in charity, the rulers by their counsel, the subjects by their obedience. The former loves its strength in the person of its masters, the latter says to its God: 'I will love thee, O Lord, my strength' (Psalm xvii, 2). Hence the wise men of the former, living according to the flesh, follow the good things either of the body, or of the mind, or of both; and such as might know God 'have not glorified him as God or given thanks: but became vain in their thoughts. And their foolish heart was darkened. For professing themselves to be wise [that is extolling themselves proudly in their wisdom], they became fools. And they changed the glory of the incorruptible God into their likeness of the image of a corruptible man and of birds, and of four-footed beasts and of creeping things [for they were either the people's leaders or followers in all these idolatries],... and worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed for ever' (Rom. i, 21). But in the heavenly city there is no wisdom of man but only the piety by which the true God is fitly worshipped, and the reward it looks for is the society of the saints...'that God may be all in all' (I Cor. xv, 28). De civ. Dei, XIV, 28 |

Such a passage

would carry great meaning for an individual like Nicholas Rolin who as Chancellor

of the Duke of Burgundy has reached the pinnacle of earthly power. Rather than

submitting to the "lust of sovereignty" and revelling in self-glory,

Rolin is reminded that his glory and strength come from God and that he should

focus on the love of God rather than self-love. ![]()

The

historiated capitals above with the images of the Fall and Expulsion of Adam

and Eve from Paradise along with the image of the drunkeness of Noah demonstrate

the corrupted nature of humanity, while the capital on the side of the Virgin

which apparently represents Melchisedech's offering to Abraham reminds us that

earthly power should subject itself to divine power. Rather than being a "citizen

of this world" one should be a "pilgrim in this world whose home is

the city of God, being by grace predestinate, by grace elect, by grace a pilgrim

here below, and by grace a citizen of heaven." (de. civ. Dei, XV,

1). This is given visual form by van Eyck with the bridge in the background

linking the two sides of the painting and thus the two cities. The cross on

the bridge and the group of figures that walk across the bridge to the side

of Christ establish the connection to pilgrimage.

The

historiated capitals above with the images of the Fall and Expulsion of Adam

and Eve from Paradise along with the image of the drunkeness of Noah demonstrate

the corrupted nature of humanity, while the capital on the side of the Virgin

which apparently represents Melchisedech's offering to Abraham reminds us that

earthly power should subject itself to divine power. Rather than being a "citizen

of this world" one should be a "pilgrim in this world whose home is

the city of God, being by grace predestinate, by grace elect, by grace a pilgrim

here below, and by grace a citizen of heaven." (de. civ. Dei, XV,

1). This is given visual form by van Eyck with the bridge in the background

linking the two sides of the painting and thus the two cities. The cross on

the bridge and the group of figures that walk across the bridge to the side

of Christ establish the connection to pilgrimage.

In Augustinian terms, rather than representing the earthly world, Jan van Eyck has used his experience of this world to create his vision of the heavenly Jerusalem. The city of churches that appears beyond Christ in the Rolin Madonna is the heavenly city of which the city on Rolin's side is the earthly embodiment.

A question that is frequently asked in discussions of the Rolin Madonna, is whose space is represented in the painting: Rolin's or the Virgin's? How can such an immediate, earthly person as Rolin appear elevated into the throne room of the Virgin? This question is reminiscent of medieval discussions about the relationship between eternity and the temporal duration of human time. For St. Augustine, there was no relationship, but theologians of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries developed the concept of what they labelled as the aevum which signified the duration that participates both in human time and eternity. In religious vision or prayer, the spirit can share in God's eternal vision. This idea can be connected to the conception of art as presented in the writings of Abbot Suger of St. Denis:

| Whence, when the many-colored beauty of the gems had called me from external cares out of delight in the comeliness of God's house, and serious meditation had induced me to concentrate on transferring the variety of holy virtues from the material to the immaterial; then I seem to see myself as if dwelling on some foreign shore of the earth neither wholly in the slime of the earth nor wholly in the purity of heaven. By God's grace I seem to be able to be transported from this inferior world to that superior one in an anagogical manner. |

These concepts of the aevum and the idea of anagogical vision are very useful constructs for understanding van Eyck's paintings. Does not van Eyck present in a work like his Rolin Madonna the experience of the aevum which is the goal of Rolin's prayer? This chamber which is clearly based on the chambre à parer or presence chamber of contemporary palace design is, in Suger's words, "neither wholly in the slime of the earth nor wholly in the purity of heaven." It is significant that van Eyck based his representation of the Virgin and Child in the Rolin Madonna on the conventional devotional image of the sedes sapientiae or the Throne of Wisdom that can be traced back to Romanesque sculpture:

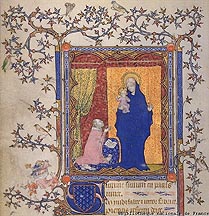

Is Rolin praying before a devotional image like Yolande de Soisson is in her Psalter Hours in the Morgan Library?:

Or is Rolin

praying before the heavenly prototype? Both answers are true following the concept

of the aevum.  A similar ambiguity of spaces can be seen in the miniatures showing Jean de Berry in prayer in his Petites heures. Is this space the Virgin's or is it the Duke's? What is clear is that the artist is connecting this image of prayer to the images of the chamber we saw in the presentation images associated with the manuscripts of Jean's brother, Charles V. Rolin in the context of prayer uses the devotional text

and the image, in Augustinian terms, as vehicles in the wanderer's pilgrimage

to his true home. Does not Rolin model for us the stance that van Eyck would

like us to take in contemplating his images? We need to use them to go through

them to find the spiritual reality. One way that van Eyck does this is through

the relationship of different details on the picture plane. Details that in

the illusionistic space are very removed from each other are linked on the picture

plane. A prime example of this is presented again by the Rolin Madonna.

A similar ambiguity of spaces can be seen in the miniatures showing Jean de Berry in prayer in his Petites heures. Is this space the Virgin's or is it the Duke's? What is clear is that the artist is connecting this image of prayer to the images of the chamber we saw in the presentation images associated with the manuscripts of Jean's brother, Charles V. Rolin in the context of prayer uses the devotional text

and the image, in Augustinian terms, as vehicles in the wanderer's pilgrimage

to his true home. Does not Rolin model for us the stance that van Eyck would

like us to take in contemplating his images? We need to use them to go through

them to find the spiritual reality. One way that van Eyck does this is through

the relationship of different details on the picture plane. Details that in

the illusionistic space are very removed from each other are linked on the picture

plane. A prime example of this is presented again by the Rolin Madonna.

On the surface of the panel we can see that the blessing gesture of Christ in the foreground touches the end of the bridge in the background that in turn spans the central opening in the tri-partite arcade in the middle-ground. In the syntax of the painting Christ is identified as the bridge between the earthly and heavenly cities, and that Christ is the door to salvation (John 10, 9). The Trinitarian implications of the triple arcade would also not have been lost on fifteenth-century viewer.

Van Eyck uses the relationship of details on the picture plane regularly in his images. The central axis of the Arnolfini Wedding Portrait that runs through the chandelier, signature, mirror, hands, and dog is another good example. These details all point to a divine presence that joins the couple like the traditional priest in marriage images who is the embodiment of the divine presence. This reminds us that van Eyck's signature that testifies to his presence verifies his witnessing of the oath on behalf of the duke who reigns by the grace of God.

(Ghent Altarpiece: Exterior / Interior )

Ghent Altarpiece: Macrophotography

Quatrain on the frame of the painting: Pictor Hubertus e Eyck * maior quo nemo repertus Incepit* pondus* q[ue] Johannes arte secundus [Frater perfunctus]* Judoci Vijd prece fretus* Versu sexta mai vos collocat acta tueri. The painter Hubert van Eyck, greater than whom no one was found, began [this work]; and Jan, his brother, second in art, having carried through the task at the expense of Jodocus Vyd, invites you by this verse, on the sixth of May, to look at what has been done [The year 1432 is given in the red chronogram of the last line] May 6, 1432 was the baptism of Prince Joos of Burgundy, the son of Duke Philip the Good and Isabella of Portugal. This took place in the church of St John (now St. Bavo’s Cathedral). The coincidence of the dedication of the altarpiece on this day and the baptism of the Duke's son on the same day suggests the close political relationship between Jodocus Vyd and Philip the Good. |

There is, of course, also the very prominent central axis linking the God-head at the top with the dove of the Holy Spirit, the Lamb on the altar, and the baptismal font in the lower panel. We experience God through the sacraments of Baptism and Eucharist.

In designing the Berlin Madonna in the Church, van Eyck also seems to have paid attention to the positioning of details on the picture plane.

Master

of 1499, Virgin in the Church and Abbot Christiaan de Hondt, 1499. |

Jan

Gossaert, Virgin in the Church and Antonio Siciliano and St. Anthony |

||

As later copies suggest, this painting was probably originally a diptych of which the right panel is now missing. In the original format of the painting, the Madonna's glance was probably directed to a kneeling patron occupying the right wing of the diptych. If a line is traced through the eyes of the Virgin to the assumed figure in the right wing intriguing relationships are established.

The line runs from the clerestory window, through the eyes of the Virgin, through the head of the statue of the Virgin in the niche in the roodscreen, through the Angels chanting in the apse, through the choirbook in front of the angels, and to the supposed kneeling donor. As in the Rolin Madonna, the singling out of the choirbook and statue of the Virgin reminds of the function of texts and images in devotional practices. They are vehicles that are to used to go through to spiritual contemplation. In praying before the statue we imagine ourselves actually before the Virgin in the heavenly church. As Panofsky noted long ago, this is truely the heavenly church with the divine light streaming in through the north windows the beginning of our line. A secondary line can be seen to run from the eyes of Christ through the right eye of the Virgin through the head of the Virgin atop the roodscreen to the head of the Crucified Christ on the rood screen. Essential doctrines of the Incarnation and Redemption and the central role of the Church are suggested by this line.

Another possible example is presented is presented by the Madonna and Child with Canon George van der Paele. Scholars have noted that the Canon is not looking directly at Christ. Tracing a line from the Canon's eyes presents a possible explanation for this disconnect.

On the plane of the picture this line connects the Canon's eyes, with the head of Christ, with the reliquary cross, and ends with St. Donatian, the patron of the van der Paele's Bruges church. George van der Paele's angle of vision appears to be directed towards the reliquary cross and St. Donatian. This suggests the important roles relics played in the medieval church. In a tradition that can be traced back to the early church [see web-page discussing the cult of the relics in medieval art], relics like images and texts are again vehicles toward spiritual revelation. St. Jerome, as quoted by Thomas Aquinas, gives the classic justification of the cult of the relics in the following passage: " We pay honor to the martyr's relics only so that we may venerate him whose martyrs they are; we pay honor to the servants only so that the servants' honor may glorify their Lord" [Summa Theologiae, 3a, 25,6]. We thus go through the relic to the saint to get to Christ. It is this same chain that is linked by the proposed line through the painting.

In employing these relationships which are seen on the picture plane when we deny van Eyck's illusionistic space, I think van Eyck is calling attention to a spiritual vision that transcends the limitations of human sight. The eyeglasses held by George van der Paele calls attention to the limitations of his corporeal sight.