|

|

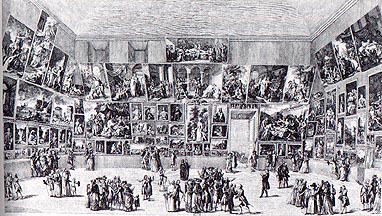

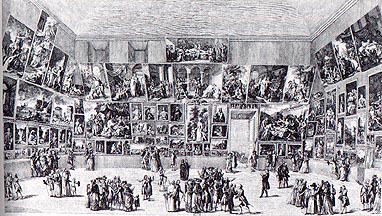

p. 1 Ambitious painting most conspicuously entered the lives of eighteenth-century Parisians in the Salon exhibitions mounted by the Academy of Painting and Sculpture. These had begun as regular events in 1737; held in odd-numbered years, except for a brief early spell of annual exhibitions, they opened on the feast-day of St. Louis (August 25) and lasted from three to six weeks. During its run, the Salon was the dominant public entertainment in the city. As visual spectacle, it was dazzling: the Salon carré of the Louvre --the vast box of a room which gave the exhibition its names-- packed with pictures from eye-level to the distant ceiling, the overflow of still-life and genre pictures spilling down the stairwells that led to the gallery; an acre of color, gleaming varnish, and teeming imagery in the midst of the tumble-down capital (the dilapidation of the Louvre itself was the subject of much contemporary complaint). "Ceaseless waves" of spectators filled the room, so the contemporary accounts tell us, the crush at times blocking the door and making movement inside impossible. The Salon brought together a broad mix of classes and social types, many of whom were unused to sharing the same leisure-time diversions. Their awkward, jostling encounters provided constant material for satirical commentary....

After 1737...[the Salon's] status was never in question, and its effects on the artistic life of Paris were immediate and dramatic. Painters found themselves exhorted in the press and in art-critical tracts to address the needs and desires of the exhibition "public"; the journalists and critics who voiced this demand claimed to speak with the backing of this public; state officials responsible for the arts hastened to assert that their /p. 2: decisions had been taken in the public's interest; and collectors began to ask, rather ominously for the artists, which pictures had received the stamp of the public's approval. All those with a vested interest in the Salon exhibitions were thus faced with the task of defining what sort of public it had brought into being.

This proved to be no easy matter, for any of those involved. The Salon exhibition presented them with a collective space that was markedly different from those in which painting and sculpture had served a public function in the past. Visual art had of course always figured in the public life of the community that produced it: civic processions up the Athenian Acropolis, the massing of Easter penitents before the portals of Chartres cathedral, the assembly of Florentine patriots around Michelangelo's David-- these would just begin the list of occasions in which art of the highest quality entered the life of the ordinary European citizen and did so in a vivid and compelling way. But prior to the eighteenth century, the popular experience of high art, however important and moving it may have been to the mass of people viewing it, was openly determined and administered from above. Artists operating at the highest levels of aesthetic ambition did not address their wider audience directly; they had first to satisfy, or at least resolve, the more immediate demands of elite individuals and groups. Whatever factors we might name which bear on the character of the art object, these were always refracted through the direct relationship between artists and patrons, that is, between artists and a circumscribed, privileged minority.

The broad public for painting and sculpture would thus have been defined in terms /p. 3 other than those of interest in the arts for their own sake. In the pre-eighteenth-century examples cited above, it was more or less identical with the ritualized assembly of the political and/or religious community as a whole --and it could be identified as such. The eighteenth-century Salon, however, marked a removal of art from ritual hierarchies of earlier communal life. There the ordinary man or woman was encouraged to rehearse before works of art the kinds of pleasure and discrimination that once had been the exclusive prerogative of the patron and his intimates.... [T]he Salon was the first regularly repeated, and free display of contemporary art in Europe to be offered in a completely secular setting and for the purpose of encouraging a primarily aesthetic response in large numbers of people.

/p. 212: [David based his Oath of the Horatii of 1785] on the same narrative material on which Corneille had based his Horaces, the tale of three sons of Horatius, heroic champions of the ancient Roman kingdom. The story of the Horatii derives ultimately from the Roman histories of Livy, Plutarch, and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. These triplets were selected to represent the city against the Curiatii, the three corresponding champions of neighboring Alba. The horrific (and sentimental) twist to the story is that the two families were related by marriage: one of the Horatii was married to a sister of the Curiatii, while their only sister, Camilla, was betrothed to one of their opponents. The two sets of brothers nevertheless fought to the death, and only one of the Roman warriors survived; thus Rome triumphed. The story has a violent coda as well: the returning victor, finding his sister mourning her betrothed, killed her in patriotic rage. Their father, however, /p. 213: putting zeal for country above all else, defended him before the assembled people of Rome and succeeded in winning his exoneration.