Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments

The Christianization of Rome and the Romanization of Christianity

The emperor said that about the noon hour, when the day was already beginning to wane, he saw with his own eyes in the sky above the sun a cross composed of light, and that there was attached to it an inscription saying, "By this conquer." At the sight, he said, astonishment seized him and all the troops who were accompanying him on the journey and were observers of the miracle. He said, moreover, that he doubted within himself what the import of this apparition could be, And while he continued to ponder and reason on its meaning, night suddenly came on; then in his sleep, the Christ of God appeared to him with the same sign which he had seen in the heavens, and commanded him to make a likeness of that sign which he had seen in the heavens, and to use it as a safeguard in all engagements with his enemies. At dawn of day, he arose, and communicated the marvel to his friends; and, then, calling together the workers in gold and precious stones, he sat in the midst of them, and described to them the figure of the sign he had seen, bidding them represent it in gold and precious stones.-- Eusebius, Life of Constantine, I, chapters 28-30. |

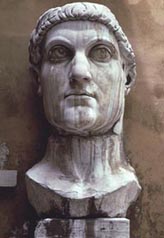

On October 28, 312, as Constantine prepared for the Battle of the Milvian Bridge against his rival Maxentius, Constantine, according to his biographer Eusebius, saw the sign of Christ in the heavens. What to the modern reader has the ring of a constructed fiction to the Late Antique and Medieval world was a fundamental reality. Just as God had called Moses to lead the Israelites to the Promised Land, God had intervened in human history to insure Constantine's victory at the Milvian Bridge. This was a central moment in western history. Before that moment, Christianity had been an outlawed religion in the Roman world. As an acknowledgement of divine aid at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Constantine, in 313, issued the Edict of Milan which granted toleration for Christianity. Constantine became imperial patron for Christianity. Although Christianity would not become the official religion of Rome until later in the fourth century, Christianity and Rome would never be the same after the time of Constantine.

Constantinian coin issued by the mint in London, 313-314. On the obverse appears the profile portrait of the cuirassed Constantine with inscription: CONSTANTINUS P F AVG; on the reverse appears the standing figure of Sol holding a globe in his left hand with inscription: SOLI INVICTO COMITI |

As characteristic

of emperors under the Dominate,

Constantine from the beginning of his career asserted his divine election.

In the coin above, Constantine pairs his

profile image on the obverse with the image of the Invincible Sun on the

reverse. Instead of the traditional inscriptions like "To the Genius

of the Roman People", Constantine's coin bears the inscription "To

the Invincible Sun my companion." The power of Constantine comes from

a divine source, and he becomes the companion of divinity. The cult of "Sol

Invictus", begun

in the third century, reflected a trend towards monotheism with Sol being

"one universal Godhead" who was "recognized under a thousand

names." Monotheism

was understood as an effective tool for consolidating power under a single

ruler who received divine election. The

remains of the palace Constantine built in the northern capital of Trier

before

his encounter with Maxentius

reflect his concern with constructing a stage for his awesome power.

The throne room, or basilica, still exists today. Although stripped of

its

original elaborate decoration, the basilica with its scale (200' X 100')

and strong central axis still echoes the imposing effect it must have

had on an ambassador approaching Constantine enthroned in the apse. The

following passage from Eusebius's biography of Constantine makes the identification

of Constantine and the Sun and captures the magnificence of his presence:

The

remains of the palace Constantine built in the northern capital of Trier

before

his encounter with Maxentius

reflect his concern with constructing a stage for his awesome power.

The throne room, or basilica, still exists today. Although stripped of

its

original elaborate decoration, the basilica with its scale (200' X 100')

and strong central axis still echoes the imposing effect it must have

had on an ambassador approaching Constantine enthroned in the apse. The

following passage from Eusebius's biography of Constantine makes the identification

of Constantine and the Sun and captures the magnificence of his presence:

| In short, as the sun, when he rises upon the earth, liberally imparts his rays of light to all, so did Constantine, proceeding at early dawn from the imperial palace, and rising as it were with the heavenly luminary, impart the rays of his own beneficence to all who came into his presence. It was scarcely possible to be near him without receiving some benefit, nor did it ever happen that any who had expected to obtain his assistance were disappointed in their hope. --Eusebius, Life of Constantine, I, 43. |

Why did Constantine convert to Christianity? We cannot discount a sincere commitment to Christianity on the part of Constantine, but the specific nature of Christianity was useful in consolidating his political control of the empire. Like the cult of "Sol Invictus," Christianity offered Constantine with the advantages of a Monotheist faith, linking a single God with a single ruler. As a mystery religion, Christianity called for the faithful to go through a rite of initiation to enter the faith. In contrast to the pagan cults that were open ended and inclusive, Christianity through the sacrament of Baptism had at its core a defined body of the faithful.

From our experience with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, we assume that religion is synonymous with belief. At the core of the dominant western religions is the question of orthodoxy. There are essential tenets of the faith that are accepted through belief. In ancient Greece and Rome, questions of doctrine and teachings were a matter of philosophy. Rather than being based on Orthodoxy, the pagan cults were founded on Orthopraxy, or the right practice of customary rituals. There was never a question of belief in the divine nature of Zeus for example. The Greek and Roman acknowledged the existence of divine powers. As Christianity developed over the first centuries after Christ, it came into contact with Classical culture. As Early Christian communities debated about the nature of Jesus, Christians came under the influence of philosophy, and developed a body of thought we know as Christian Theology. This early Christianity was noted for fractious debates over central questions like the nature of Christ and the composition of the accepted body of Christian texts.

While the Edict of Milan granted religious toleration, Constantine was very much concerned about the unity of Christianity. In 313, the same year of the edict, Constantine sent a letter to a prefect in northern Africa to suppress the Donatists, a schismatic Christian sect:

| I consider it absolutely contrary to the divine law that we should overlook such quarrels and contentions, whereby the Highest Divinity may perhaps be moved to wrath, not only against the human race, but also against me myself, to whose care He has, by His celestial will, committed the government of all earthly things, and that He may so far moved as to take some untoward step. For I shall really and fully be able to feel secure and always to hope for prosperity and happiness from the ready kindness of the most mighty God, only when I see all venerating the most holy God in the proper cult of the catholic religion with harmonious brotherhood of worship.--Jame Carroll, Constantine's Sword..., p. 184. |

Constantine understood himself to be the Thirteenth Apostle of Christ charged with leading a catholic or universal church. Establishing orthodox doctrine was a central concern for Constantine. To that end he convened an international council of bishops in 325 at Nicea. At question was who among the different factions should embody the catholic church. The product of the council was the core of what is known as the Nicene Creed that is still recited in churches today:

| We believe (I believe) in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, and born of the Father before all ages. (God of God) light of light, true God of true God. Begotten not made, consubstantial to the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven. And was incarnate of the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary and was made man; was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate, suffered and was buried; and the third day rose again according to the Scriptures. And ascended into heaven, sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead, of whose Kingdom there shall be no end. And (I believe) in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father (and the Son), who together with the Father and the Son is to be adored and glorified, who spoke by the Prophets. And one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. We confess (I confess) one baptism for the remission of sins. And we look for (I look for) the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen. |

This creed that was intended to define orthodox Christianity can be read as a political document as well.

With Constantine we see the coming together of two institutions which will be central to western civilization to this day. Rome through its military, tradition of law, administration, and culture had established an Empire that would be a model of political hegemony to this day. Christianity with its messianic message of human salvation at the end of time through the death and resurrection of Christ provided a vision of a unified and orthodox faith that would be inextricably linked to political authority. The vision of a Heavenly Kingdom of God presented in Orthodox Christianity would be the model for the Earthly Kingdom. Orthodox belief was essential to political loyalty. A critical role for the ruler was defending the faith from heresy. Aren't modern beliefs in patriotism echoes of assertions of orthodoxy?

Despite our Constitutional separation of Church and State, the linking of Christianity and political authority is still with us. Consider for example the Pledge of Allegiance, our secular version of the Nicene Creed: I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Don't we still swear oaths on the Bible? Doesn't the expression "In God We Trust" still appear on our money? We justify such inconsistencies by defining them as civil religious expression that is inclusive rather than exclusive, but can an atheist be possibly included in such a conception? The vision of Christianity still plays a central role in the formation of the political ideology of our leaders. See the Frontline show entitled The Jesus Factor that explores the influence of Christianity on George W. Bush. President Bush during his Press Conference on April 13, 2004 made the following statement: "I also have this belief, strong belief that freedom is not this country's gift to the world. Freedom is the Almighty's gift to every man and woman in this world. And as the greatest power on the face of the earth we have an obligation to help the spread of freedom." [see David Suskind,"Without a Doubt," Magazine section, New York Times, Sunday, October 16, 2004]

Supplementary Website:

From Jesus to Christ: Why did Christianity Succeed? See especially the segment entitled Legitimization under Constantine. For the formation of the Christian Canon. Particularly interesting is the non-canonical Gospel of Thomas. It presents a radically different conception of the Kingdom of God and of Christ from that found in canonical texts like the Gospel of John. Elaine Pagels presents an interesting discussion on the Gospel of Thomas on The Frontline site. Pagels has developed her discussion in a book entitled Beyond Belief: the Secret Gospel of Thomas.