The following are excerpts from Carol Duncan, "The MoMA's Hot Mamas," repr. in The Expanding Discourse, eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, pp.346-357.

/p. 348: In theory, museums are public spaces dedicated to the spiritual enhancement of all who visit them. In practice, however, museums are prestigious and powerful engines of ideology. They are modern ritual spaces in which visitors enact complex and often deep psychic dramas about identity --dramas that the museum's stated, consciously intended programs do not and cannot acknowledge overtly. Like those of all great museums, the MoMA's ritual transmits a complex ideological signal. My concern here is with only a portion of that signal --the portion that addresses sexual identity. I shall argue that the collection's recurrent images of sexualized female bodies actively masculinize the museum as a social environment. Silently and surreptiously, they specify the museum's ritual of spiritual quest as a male quest, /p. 349 as they mark the larger project of modern art as primarily a male endeavor.

If we understand the modern art museum as a ritual of male transcendence, if we see it as organized around male fears, fantasies, and desires, then the quest for spiritual transcendence on the one hand and the obsession with a sexualized female body on the other, rather than appearing unrelated or contradictory, can be seen as part of a larger, psychologically integrated whole....

Even works that eschews such imagery and gives itself to the drive for abstract, transcendent truth may also speak of these fears, in the very act of fleeing the realm of matter (mater) and biological need that is woman's traditional domain. How often modern masters have sought to make their work speak of higher realms --of air, light, the mind, the cosmos-- realms that exist above a female, biological earth.....

Since the heroes of this ordeal are generically men, the presence of women artists in this mythology can be only an anomaly. Women artists, especially if they exceed the standard token number, tend to degender the ritual ordeal. Accordingly, in the MoMA and other museums, their numbers are kept well below the point where they might effectively dilute the masculinity. The female presence is necessary only in the form of imagery. Of course men, too, are occasionally represented. But unlike women, who are seen primarily as sexually accessible bodies, men are portrayed as physically and mentally active beings who creatively shape their world and ponder its meanings....

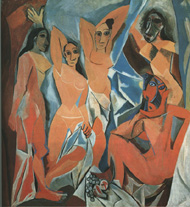

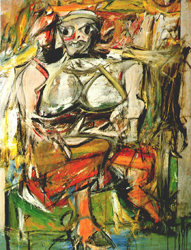

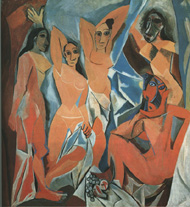

/p. 350: de Kooning's Woman I and Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon are two of art history's most important female images. They are key objects in the MoMA's collection and highly effective in maintaining the museum's masculinized environment [they are "seminal" works of Modernism].

The museum has always hung these works with precise attention to their strategic roles in the story of modern art. Both before and after the 1984 expansion, de Kooning's Woman I hung at the threshold to the spaces containing the big Abstract Expressionist "breakthroughs" --the New York school's final collective leap into absolutely pure, abstract, nonreferential transcendence: Pollock's artist and psychic free flights, Rothko's sojourns in the luminous depths of a universal self, Newman's heroic confrontations with the sublime..., and so on. And always seated at the doorway to these moments of ultimate freedom and purity, and literally helping to frame them, has been Woman I. So important is her presence just there, that when she has to go on loan, Woman II appears to take her place. With good reason. De Kooning's Women are exceptionally successful ritual artifacts, and they masculinize the museum's space with great efficiency.

The woman figure had been emerging gradually in de Kooning's work in the course of the 1940s. By 1951-52, it had fully revealed itself in Woman I as a big, bad mama --vulgar, sexual, and dangerous. De Kooning imagines her facing us with iconic frontality --large, bulging eyes; open, toothy mouth; massive breasts. The suggestive pose is just a knee movement away from open-thighed display of the vagina, the self-exposing gesture of mainstream pornography.

These features are not unique in the history of art. They appear in ancient and tribal cultures, as well as in modern pornography and graffiti. Together, they constitute a well-known figure type. The Gorgon of ancient Greek art , an instance of that type, bears a striking resemblance to de Kooning's Woman I and, like her, simultaneously suggests and avoids the explicit act of sexual self-display that elsewhere characterizes the type.

|

|

/ p. 351 In her guise as the Gorgon witch..., the terrible aspect of the mother goddess, her lust for blood and her deadly gaze, is emphasized. Especially today, when the myths and rituals that may have suggested other meanings have been lost --and when modern psychoanalytic ideas are likely to color any interpretation-- the figure appears especially intended to conjure up infantile feelings of powerlessness before the mother and the dread of castration: in the open jaw can be read the vagina dentata --the idea of a dangerous, devouring vagina, too horrible to depict, and hence transposed to the toothy mouth.

Feelings of inadequacy and vulnerability before mature women are common (if not always salient) phenomena in male psychic development. Such myths as the story of Perseus and such visual images as the Gorgon can play a role in mediating that development by extending and re-treating on the cultural plane its core psychic experience and accompanying defenses. Thus objectified and communally shared in imagery, myth, and ritual, such individual fears and desires may achieve the status of higher, universal truth. In this sense, the presence of Gorgons on Greek temples, important houses of cult worship (they also appeared on Christian church walls) -- is paralleled by Woman I's presence in a high-cultural house of the modern world.

The head of de Kooning's Woman I is so like /p.352 that of the archaic Gorgon that the reference could well be intentional, especially since the artist and his friends placed great store in ancient myths and primitive images and likened themselves to archaic and tribal shamans. Writing about de Kooning's Women, Thomas Hess echoed this claim in a passage comparing de Kooning's artistic ordeal to that of Perseus, slayer of the Gorgon. Hess is arguing that de Kooning's Women grasp an elusive, dangerous truth "by the throat."

And truth can be touched only by complications, ambiguities and paradox, so, like the hero who looked for Medusa in the mirroring shield, he must study her flat, reflected image every inch of the way.

[Duncan includes much of the material from this essay in a chapter on the Modern Art museum in her book Civilizing Rituals. She does extend her argument in this later version:

p. 122: Thomas Hess understood exactly the way in which de Kooning's Women enabled one to both experience the dangerous realm of woman-matter-nature and symbolically escape into male-culture-enlightenment. The following passage is a kind of brief user's manual for any of de Kooning's Women.... It also articulates the core of the ritual ordeal I have been describing. Hess begins with characterizing de Kooning's materials. They are clearly female, engulfing, and slimy, and must be controlled by the skilled, instrument-wielding hands of a male:

| There are the materials themselves, fluid, viscous, wet or moist, slippery, fleshy and organic in feel; spreading, thickening or thinning under the artist's hands. Could they be compared to the primal ooze, the soft underlying mud, from which all life has sprung? To nature? |

Now comes the artist, brandishing his phallus-tool, to pierce, cut, and penetrate the female flesh:

| And the instruments of the artist are, by contrast, sharp, like the needlepoint of a pencil; or slicing, like the whiplash motion of the long brush. |

And finally, the symbolic act of the mind that the viewer witnesses and re-lives:

| Could not the artist at work, forcing his materials to take shape and become form [be a] paradigm? The artist becomes the tragicomic hero who must go to war against the elements of nature in the hope of making contact with them. (Thomas Hess, Willem de Kooning: Drawings, New York, 1972, p. 18) ] |

p. 352 (cont.) The Woman is not only monumental and iconic. In high-heeled shoes and brassier, she is also lewd, her pose indecently teasing. De Kooning acknowledged her oscillating character, claiming for her a likeness not only to serious art --ancient icons and high-art nudes-- but also to pinups and girlie pictures of the vulgar present. He saw her as simultaneously frightening and ludicrous. The ambiguity of the figure, its power to resemble an awesome mother goddess as well as a modern burlesque queen, provides a fine cultural, psychological, and artistic field in which to enact the modern myth of the artist-hero --the hero whose spiritual ordeal becomes the stuff of ritual in the public space of the museum. As a powerful and threatening woman, it is she who must be confronted and transcended --gotten past on the way to enlightenment. At the same time, her vulgarity, her "girlie" side --de Kooning called it her "silliness" --renders her harmless (or is it contemptible?) and denies the terror and dread of her Medusa features. The ambiguity of the image thus gives the artist (and the viewer) both the experience of danger and a feeling of overcoming it. Meanwhile, the suggestion of pornographic self-display... specifically addresses itself to the male viewer. With it, de Kooning knowingly and assertively exercises his patriarchal privilege of objectifying male sexual fantasy as high culture....

/p. 353 Of course before de Kooning...created [his] ambiguous self-displaying women, there was Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon of 1907. The work was conceived as an extraordinarily ambitious statement --it aspires to revelation-- about the meaning of Woman. In it, all women belong to a universal category of being, existing across time and place. Picasso used ancient and tribal art to reveal woman's universal mystery: Egyptian and Iberian sculpture on the left, and African art on the right. The figure on the lower right looks as if was directly inspired by some primitive or archaic deity. Picasso would have known such figures from his visits to the ethnographic art collections in the Trocadero.... Significantly, Picasso wanted her to be prominent --she is the nearest and largest of all the figures. At this stage [refers to prepatory drawing (fig. 4)], Picasso also planned to include a male student on the left and, in the axial center of the composition, a sailor --a figure of horniness incarnate. The self-displaying woman was to have faced him, her display of genital turned away from the viewer.

In the finished work, the male presence has been removed from the image and relocated in the /p. 354 viewing space before it. What began as a depicted male-female confrontation thus became a confrontation between viewer and image.... As restructured, the work forcefully asserts to both men and women the privileged status of male viewers -- they alone are intended to experience the full impact of this most revelatory moment.....

Finally, the mystery that Picasso unveils about women is also an art-historical lesson. In the finished work, the women have become stylistically differentiated so that one looks not only at present-tense whores but also back down into the ancient and primitive past, with the art of "darkest Africa" and works representing the beginnings of Western culture (Egyptian and Iberian idols) placed on a single spectrum. Thus does Picasso use art history to argue his thesis: that the awesome goddess, the terrible witch, and the lewd whore are but facets of a single many-sided creature, in turn threatening and seductive, imposing and self-abasing, dominating and powerless -- and always the psychic property of a male imagination. [ Civilizing Rituals ,p. 117: In this context, the use of African art constitutes not an homage to "the primitive" but a means of framing woman as "other," one whose savage animalistic inner self stands opposed to the civilized, reflective male's.] Picasso also implies that truly great, powerful, and revelatory art has always been and must be built upon such exclusively male property.

That museums are not neutral institutions and that they become a site for rituals of male transcendence is brought about by many of the works developed by the feminist collective known as the Guerrilla Girls like the following example:

The following is an excerpt

from a very influential article by Leo Steinberg, an eminent art historian and

art critic. Note the language that Steinberg uses and how it continues the sexual

politics discussed by Duncan above:

"Comparison with the numerous studies for the Demoiselles revealed

how tenaciously Picasso pursued this end; he was resolved to undo the continuities

of form and field which Western art had so long taken for granted. The famous

stylistic rupture at right turned out to be merely a consummation. Overnight,

the contrived coherences of representational art --the feigned unities of time

and place, the stylistic consistencies-- all were declared to be fictional.

The Demoiselles confessed itself a picture conceived in duration and

delivered in spasms. In this one work Picasso discovered that the demands of

discontinuity could be met on multiple levels: by cleaving depicted flesh; by

elision of limbs and abbreviation; by slashing the web of connecting space;

by abrupt changes of vantage; and by a sudden stylistic shift at the climax.

Finally, the insistent staccato of the presentation was found to intensify the

picture's address and symbolic charge: the beholder, instead of observing a

roomful of lazing whores, is targetted from all sides. So far from suppressing

the subject, the mode of organization heightens its flagrant eroticism."

The major German, 20th century painter, Kandinsky, describes the act of painting in the following terms:

Thus I learned to battle with the canvas, to come to know it as a being resisting my wish (dream), and to bend it forcibly to this wish. At first it stands there like a pure chaste virgin...And then comes the willful brush which first here, then there, gradually conquers it with all the energy peculiar to it, like a European colonist.

View of a gallery in the Museum of Modern Art: in the foreground is Rodin's St. John the Baptist and the painting on the far wall is Cezanne's Walking Man. Photograph from Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals. p. 105. Duncan uses the photograph to illustrate the point that the narrative of Modern Art in MoMA is introduced by the works of Rodin and Cezanne. While Duncan's essay focuses on questions of gender, her photograph makes an important connection to the works of Fred Wilson who focuses on the question of the representation of race in the museum.

Fred Wilson, Guarded View, 1991.

Fred Wilson, Whipping Post, from Exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society, Mining the Museum, 1992.

(Judith Stein. Sins of Omission: Fred Wilson's Mining the Museum)

Fred Wilson, Mine/Yours, 1995