Art

Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH

209 Home | ARTH 209 Assignments

Excerpts

from Homer, Odyssey, IX

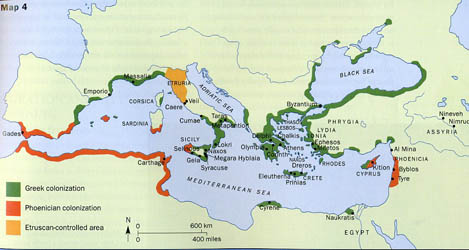

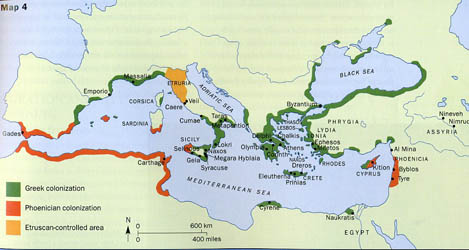

The end of the eighth

century and the seventh century was marked in Greek culture by the process

of colonization, when the Greek city states established colonies in other

parts of the Mediterranean world. This period is also called the Orientalizing

period. This label given by modern scholars is a reference to the Eastern

or Oriental influences on Greek culture brought about by the contact the Greeks

had with the Ancient Near Eastern cultures during this period of colonization.

The Odyssey can be read from these perspectives. In the first part of this

passage, Odysseus and his cohorts arrive on the island of the Cyclopes and

they assess their environs. Note the colonist’s perspective here as they

assess the adjacent island. The most famous part of Odyssey IX recounts Odysseus’s

encounter with the Cyclops Polyphemos. In this context the Cyclopes can be

read as the non-Greek, “barbarian.” It is also a good example of

heroic “arete”. Try to articulate the values and priorities of Greek

culture re-presented in these passages.

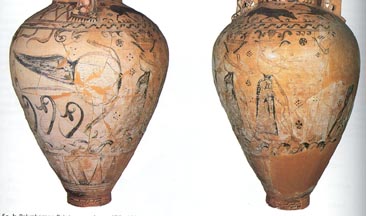

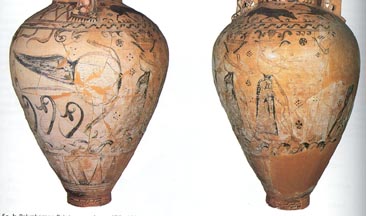

The amphora

above was found at an ancient graveyard at Eleusis. It was a gravemarker for

a male's grave. It is an important monument in the development of narrative

representations. On the belly of the vase is represented the story of the

hero Perseus fleeing with the aid of Athena from the Gorgons after he had

beheaded Medusa.

This

story was widely popular in the art of the 7th and 6th centuries. It is interesting

to note the experimental nature of this narrative by observing the form of

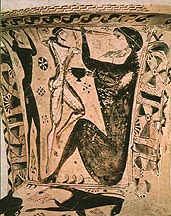

the gorgons that do not reflect the later canonical form. On the neck of this

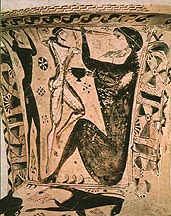

vase is represented the story of Odysseus Blinding Polyphemos:

Compare

this representation to the Homeric account that follows. Note the thematic

connections of the stories shown on this vase.

[105] “Thence we

sailed on, grieved at heart, and we came to the land of the Cyclopes, an overweening

and lawless folk, who, trusting in the immortal gods, plant nothing with their

hands nor plough; but all these things spring up for them without sowing or

ploughing, [110] wheat, and barley, and vines, which bear the rich clusters

of wine, and the rain of Zeus gives them increase. Neither assemblies for

council have they, nor appointed laws, but they dwell on the peaks of lofty

mountains in hollow caves, and each one is lawgiver [115] to his children

and his wives, and they reck nothing one of another.

“Now there is a level

isle that stretches aslant outside the harbor, neither close to the shore

of the land of the Cyclopes, nor yet far off, a wooded isle. Therein live

wild goats innumerable, for the tread of men scares them not away, [120] nor

are hunters wont to come thither, men who endure toils in the woodland as

they course over the peaks of the mountains. Neither with flocks is it held,

nor with ploughed lands, but unsown and untilled all the days it knows naught

of men, but feeds the bleating goats. [125] For the Cyclopes have at hand

no ships with vermilion cheeks, nor are there ship-wrights in their land who

might build them well-benched ships, which should perform all their wants,

passing to the cities of other folk, as men often cross the sea in ships to

visit one another — [130] craftsmen, who would have made of this isle

also a fair settlement. For the isle is nowise poor, but would bear all things

in season. In it are meadows by the shores of the grey sea, well-watered meadows

and soft, where vines would never fail, and in it level ploughland, whence

[135] they might reap from season to season harvests exceeding deep, so rich

is the soil beneath; and in it, too, is a harbor giving safe anchorage, where

there is no need of moorings, either to throw out anchor-stones or to make

fast stern cables, but one may beach one's ship and wait until the sailors'

minds bid them put out, and the breezes blow fair. [140] Now at the head of

the harbor a spring of bright water flows forth from beneath a cave, and round

about it poplars grow. Thither we sailed in, and some god guided us through

the murky night; for there was no light to see, but a mist lay deep about

the ships and the moon [145] showed no light from heaven, but was shut in

by clouds. Then no man's eyes beheld that island, nor did we see the long

waves rolling on the beach, until we ran our well-benched ships on shore.

And when we had beached the ships we lowered all the sails [150] and ourselves

went forth on the shore of the sea, and there we fell asleep and waited for

the bright Dawn.

“As soon as early

Dawn appeared, the rosy-fingered, we roamed throughout the isle marvelling

at it; and the nymphs, the daughters of Zeus who bears the aegis, roused [155]

the mountain goats, that my comrades might have whereof to make their meal.

Straightway we took from the ships our curved bows and long javelins, and

arrayed in three bands we fell to smiting; and the god soon gave us game to

satisfy our hearts. The ships that followed me were twelve, and to each [160]

nine goats fell by lot, but for me alone they chose out ten....

“As soon as early Dawn

appeared, the rosy-fingered, he [the cyclops Polyphemus] rekindled the fire

and milked his goodly flocks all in turn, and beneath each dam placed her young.

[310] Then, when he had busily performed his tasks, again he seized two men

at once and made ready his meal. And when he had made his meal he drove his

fat flocks forth from the cave, easily moving away the great door-stone; and

then he put it in place again, as one might set the lid upon a quiver. [315]

Then with loud whistling the Cyclops turned his fat flocks toward the mountain,

and I was left there, devising evil in the deep of my heart, if in any way I

might take vengeance on him, and Athena grant me glory.

“Now this seemed to

my mind the best plan. There lay beside a sheep-pen a great club of the Cyclops,

[320] a staff of green olive-wood, which he had cut to carry with him when dry;

and as we looked at it we thought it as large as is the mast of a black ship

of twenty oars, a merchantman, broad of beam, which crosses over the great gulf;

so huge it was in length and in breadth to look upon. [325] To this I came,

and cut off therefrom about a fathom's length and handed it to my comrades,

bidding them dress it down; and they made it smooth, and I, standing by, sharpened

it at the point, and then straightway took it and hardened it in the blazing

fire. Then I laid it carefully away, hiding it beneath the dung, [330] which

lay in great heaps throughout the cave. And I bade my comrades cast lots among

them, which of them should have the hardihood with me to lift the stake and

grind it into his eye when sweet sleep should come upon him. And the lot fell

upon those whom I myself would fain have chosen; [335] four they were, and I

was numbered with them as the fifth. At even then he came, herding his flocks

of goodly fleece, and straightway drove into the wide cave his fat flocks one

and all, and left not one without in the deep court, either from some foreboding

or because a god so bade him. [340] Then he lifted on high and set in place

the great door-stone, and sitting down he milked the ewes and bleating goats

all in turn, and beneath each dam he placed her young. But when he had busily

performed his tasks, again he seized two men at once and made ready his supper.

[345] Then I drew near and spoke to the Cyclops, holding in my hands an ivy

bowl of the dark wine:

“‘Cyclops, take

and drink wine after thy meal of human flesh, that thou mayest know what manner

of drink this is which our ship contained. It was to thee that I was bringing

it as a drink offering, in the hope that, touched with pity, [350] thou mightest

send me on my way home; but thou ragest in a way that is past all bearing. Cruel

man, how shall any one of all the multitudes of men ever come to thee again

hereafter, seeing that thou hast wrought lawlessness?’

“So I spoke, and he

took the cup and drained it, and was wondrously pleased as he drank the sweet

draught, and asked me for it again a second time:

[355] “‘Give it

me again with a ready heart, and tell me thy name straightway, that I may give

thee a stranger's gift whereat thou mayest be glad. For among the Cyclopes the

earth, the giver of grain, bears the rich clusters of wine, and the rain of

Zeus gives them increase; but this is a streamlet of ambrosia and nectar.’

[360] “So he spoke,

and again I handed him the flaming wine. Thrice I brought and gave it him, and

thrice he drained it in his folly. But when the wine had stolen about the wits

of the Cyclops, then I spoke to him with gentle words:

“‘Cyclops, thou

askest me of my glorious name, and I [365] will tell it thee; and do thou give

me a stranger's gift, even as thou didst promise. Noman is my name, Noman do

they call me — my mother and my father, and all my comrades as well.’

“So I spoke, and he

straightway answered me with pitiless heart: ‘Noman will I eat last among

his comrades, [370] and the others before him; this shall be thy gift.’

“He spoke, and reeling

fell upon his back, and lay there with his thick neck bent aslant, and sleep,

that conquers all, laid hold on him. And from his gullet came forth wine and

bits of human flesh, and he vomited in his drunken sleep. [375] Then verily

I thrust in the stake under the deep ashes until it should grow hot, and heartened

all my comrades with cheering words, that I might see no man flinch through

fear. But when presently that stake of olive-wood was about to catch fire, green

though it was, and began to glow terribly, [380] then verily I drew nigh, bringing

the stake from the fire, and my comrades stood round me and a god breathed into

us great courage. They took the stake of olive-wood, sharp at the point, and

thrust it into his eye, while I, throwing my weight upon it from above, whirled

it round, as when a man bores a ship's timber [385] with a drill, while those

below keep it spinning with the thong, which they lay hold of by either end,

and the drill runs around unceasingly. Even so we took the fiery-pointed stake

and whirled it around in his eye, and the blood flowed around the heated thing.

And his eyelids wholly and his brows round about did the flame singe [390] as

the eyeball burned, and its roots crackled in the fire. And as when a smith

dips a great axe or an adze in cold water amid loud hissing to temper it —

for therefrom comes the strength of iron — even so did his eye hiss round

the stake of olive-wood. [395] Terribly then did he cry aloud, and the rock

rang around; and we, seized with terror, shrank back, while he wrenched from

his eye the stake, all befouled with blood, and flung it from him, wildly waving

his arms. Then he called aloud to the Cyclopes, who [400] dwelt round about

him in caves among the windy heights, and they heard his cry and came thronging

from every side, and standing around the cave asked him what ailed him:

“‘What so sore

distress is thine, Polyphemus, that thou criest out thus through the immortal

night, and makest us sleepless? [405] Can it be that some mortal man is driving

off thy flocks against thy will, or slaying thee thyself by guile or by might?’

“‘Then from out

the cave the mighty Polyphemus answered them: ‘My friends, it is Noman

that is slaying me by guile and not by force.’

“And they made answer

and addressed him with winged words: [410] ‘If, then, no man does violence

to thee in thy loneliness, sickness which comes from great Zeus thou mayest

in no wise escape. Nay, do thou pray to our father, the lord Poseidon.’

“So they spoke and

went their way; and my heart laughed within me that my name and cunning device

had so beguiled. [415] But the Cyclops, groaning and travailing in anguish,

groped with his hands and took away the stone from the door, and himself sat

in the doorway with arms outstretched in the hope of catching anyone who sought

to go forth with the sheep — so witless, forsooth, he thought in his heart

to find me. [420] But I took counsel how all might be the very best, if I might

haply find some way of escape from death for my comrades and for myself. And

I wove all manner of wiles and counsel, as a man will in a matter of life and

death; for great was the evil that was nigh us. And this seemed to my mind the

best plan. [425] Rams there were, well-fed and thick of fleece, fine beasts

and large, with wool dark as the violet. These I silently bound together with

twisted withes on which the Cyclops, that monster with his heart set on lawlessness,

was wont to sleep. Three at a time I took. The one in the middle in each case

bore a man, [430] and the other two went, one on either side, saving my comrades.

Thus every three sheep bore a man. But as for me — there was a ram, far

the best of all the flock; him I grasped by the back, and curled beneath his

shaggy belly, lay there face upwards [435] with steadfast heart, clinging fast

with my hands to his wondrous fleece. So then, with wailing, we waited for the

bright dawn.

“As soon as early Dawn

appeared, the rosy-fingered, then the males of the flock hastened forth to pasture

and the females bleated unmilked about the pens, [440] for their udders were

bursting. And their master, distressed with grievous pains, felt along the backs

of all the sheep as they stood up before him, but in his folly he marked not

this, that my men were bound beneath the breasts of his fleecy sheep. Last of

all the flock the ram went forth, [445] burdened with the weight of his fleece

and my cunning self. And mighty Polyphemus, as he felt along his back, spoke

to him, saying:

“‘Good ram, why

pray is it that thou goest forth thus through the cave the last of the flock?

Thou hast not heretofore been wont to lag behind the sheep, but wast ever far

the first to feed on the tender bloom of the grass, [450] moving with long strides,

and ever the first didst reach the streams of the river, and the first didst

long to return to the fold at evening. But now thou art last of all. Surely

thou art sorrowing for the eye of thy master, which an evil man blinded along

with his miserable fellows, when he had overpowered my wits with wine, [455]

even Noman, who, I tell thee, has not yet escaped destruction. If only thou

couldst feel as I do, and couldst get thee power of speech to tell me where

he skulks away from my wrath, then should his brains be dashed on the ground

here and there throughout the cave, when I had smitten him, and my heart [460]

should be lightened of the woes which good-for-naught Noman has brought me.’

“So saying, he sent

the ram forth from him. And when we had gone a little way from the cave and

the court, I first loosed myself from under the ram and set my comrades free.

Speedily then we drove off those long-shanked sheep, rich with fat, [465] turning

full often to look about until we came to the ship.