|

Constantine's conversion did not mean the end of paganism (if you are interested in exploring this end of Paganism read James O'Donnell's article on the Web entitled "The Demise of Paganism"). Especially in Rome which was the home of the staunchly conservative members of the Senatorial class, paganism was still active at the end of the fourth century. It was then that Theodosius issued edicts banning paganism and making Christianity the official religion of Rome. The old guard in Rome did not want to give up their "pietas" to their ancestral cults. This is best represented by a famous debate between the Pagan Symmachus and Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, over the maintenance of the Altar of Victory. Dating back to Roman Republican days and located in the Roman Senate, the Altar of Victory was one of the most important symbols of paganism. Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (c. 354-410), the Prefect of Rome and member of one of the most prominent Roman families of the period (see entry for the Symmachus family in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica) argues:

"Excellent Emperors, Fathers of your country, respect these years to which pious rites have conducted me. Let me use the ancient ceremonies, for I do not repent of them. Let me live in my own way, for I am free. The worship reduced the world under my laws; these sacred rites repulsed Hannibal from the walls and the Gauls from the Capitol. Am I reserved for this, to be censured in my old age? I am not unwilling to consider the proposed decree, and yet late and ignominious is the reformation of old age.

We pray therefore for a respite for the gods of our fathers and our native gods. That which all venerate should in fairness be accounted as one. We look on the same stars, the heaven is common to us all, the same world surrounds us. What matters it by what arts each of us seeks for truth? We cannot arrive by one and the same path at so great a secret....

The attitudes expressed by Symmachus find an eloquent visual parallel in a famous ivory diptych bearing the names: Nicomachi and Symmachi:

|

The left panel now in the Musée de Cluny in Paris show a priestess dedicated to the cults of Ceres and Cybele, while the right panel now in the Victoria Albert Museum in London shows a priestess making an offering dedicated to Bacchus and Jupiter. It is likely that the diptych was made to celebrate the marriage of members of these two prominent Roman Senatorial families. The connections to the pagan past is not only evident in the subject matter, but is also apparent in the style of the panels. The conception of the figures especially evident in the rich drapery patterns can be traced back to fifth century Greek works such as the pedimental sculpture of the Parthenon:

Or the famous late fifth century relief of Nike binding her sandal from the parapet of the Temple of Athena Nike:

Although the style of the diptych clearly emulates this high Classical style, careful examination of the conception of details justifies the characterization of these works as classicizing rather than classical.

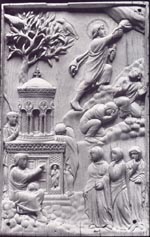

While Senatorial families like the Nicomachi and Symmachi were trying to preserve their pagan heritage, other Senatorial families were becoming converted to Christianity. While accepting the new religion, these patrons still wanted to hold onto the Classical tradition. An ivory panel now in Munich showing the Holy Women at the Tomb and the Ascension of Christ shows how the Christian subject matter has been converted to the style and conventions of the Classical tradition:

The gestures and mood of the women can be connected to the language of pathos developed in Greek art as exemplified by the fourth century B.C. so-called Mourners Sarcophagus:

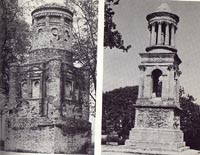

The conception of Christ's tomb is clearly connected to the tradition of Roman tomb architecture that would be produced for Senatorial families:

The rural setting of the tomb with the tree has significant parallels to the conventions of so-called sacral idyllic landscapes found in Roman painting:

A striking feature of art of the Early Christian period is the plurality of styles. In the comparison below observe the differences in style and relate these differences in style to the different artistic traditions.