Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments

Baccio Bandinelli, Self Portrait, c 1530.

This self portrait by the Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli testifies to the transformation in the  concept

of the artist. Instead of showing a workshop with its members actively collaborating

on projects, Bandinelli depicts himself in isolation in a splendid, classical

architectural setting. He wears a gold chain with a pendant identifiable as

the symbol of the chivalric Order of St. James (Santiago). As this gold chain

suggests, Baccio Bandinelli fashioned himself as a court artist. His most

important commissions were from the Medici Dukes of Florence as well as the

Papacy. Bandinelli had sought the patronage of the Emperor Charles V and

had presented him with various gifts including a relief of the Deposition. In response to these gifts Charles V rewarded Bandinelli with knighthood of the Order of St. James in October 1529. To support his claim to the title of knighthood, Baccio claimed descent from the noble family of Bandinelli from Siena. In his Memoriale, Bandinelli writes the following account in which he identifies himself as a courtier of noble status:

concept

of the artist. Instead of showing a workshop with its members actively collaborating

on projects, Bandinelli depicts himself in isolation in a splendid, classical

architectural setting. He wears a gold chain with a pendant identifiable as

the symbol of the chivalric Order of St. James (Santiago). As this gold chain

suggests, Baccio Bandinelli fashioned himself as a court artist. His most

important commissions were from the Medici Dukes of Florence as well as the

Papacy. Bandinelli had sought the patronage of the Emperor Charles V and

had presented him with various gifts including a relief of the Deposition. In response to these gifts Charles V rewarded Bandinelli with knighthood of the Order of St. James in October 1529. To support his claim to the title of knighthood, Baccio claimed descent from the noble family of Bandinelli from Siena. In his Memoriale, Bandinelli writes the following account in which he identifies himself as a courtier of noble status:

| Being desirous to bring splendor to my lineage, I took the occasion offered by Charles V's trip to Italy...to ask the emperor to induct me into the Order of Santiago. I was a courtier in the suite of the pope, who testified that I was born into the very ancient and very noble house of the Bandinelli of Siena...many princes and lords of the Order ignorantly opposed my nomination, saying that as a sculptor I did not deserve it.... |

In Renaissance and Baroque art the gold chain is a regular feature in many self-portraits. The gold chain signified status at court and a reciprocal relationship between the artist and ruler. In return for the ruler's favor and financial support, the court artist was expected to glorify him and his office. Titian's Self Portrait illustrates this type of portrait with a gold chain. In 1533, Charles V appointed Titian Count Palatine and raised him to the rank of a Knight of the Golden Spur. Notice how Titian does not show himself with the normal "tools of the trade," but is shown wearing a fur coat and satin blouse appropriate to an individual of high social standing. Contemporary descriptions of Titian identify him as a courtier. Vasari writes: "[He was] extremely courteous, with very good manners and the most pleasant personality and behavior." Dolce presents the following description:

In Renaissance and Baroque art the gold chain is a regular feature in many self-portraits. The gold chain signified status at court and a reciprocal relationship between the artist and ruler. In return for the ruler's favor and financial support, the court artist was expected to glorify him and his office. Titian's Self Portrait illustrates this type of portrait with a gold chain. In 1533, Charles V appointed Titian Count Palatine and raised him to the rank of a Knight of the Golden Spur. Notice how Titian does not show himself with the normal "tools of the trade," but is shown wearing a fur coat and satin blouse appropriate to an individual of high social standing. Contemporary descriptions of Titian identify him as a courtier. Vasari writes: "[He was] extremely courteous, with very good manners and the most pleasant personality and behavior." Dolce presents the following description:

| [H]e is a brilliant conversationalist, with powers of intellect and judgment which are quite perfect in all contingencies, and a pleasant and gentle nature. He is affable and copiously endowed with extreme courtesy of behavior. And the man who talks to him once is bound to fall in love with him for ever and always. |

Service at court usually meant liberation from guild regulations and freedom from the rules that governed the trade. As Chapman writes in her book on Rembrandt Self-portraits (p.51): "The chain did not only signify a painter's rank and achievement. It also had important implications for the status of his profession.... Since chains were traditionally bestowed for intellectual pursuits, they signaled that painters had risen above craftsmen, that painting had entered the liberal arts."

Humanists had redefined painting and sculpture as liberal activities associated with the intellect. Thus the status of the artist was elevated from the more lowly status of Antiquity and the Middle Ages when the practice of art was associated with the mechanical arts and not the liberal arts. Humanists saw the foundation of art in the science of geometry one of the traditional disciplines of the Quadrivium, the four mathematical sciences of the Seven Liberal Arts. Geometry concerned itself with essential reality, the underlying order of nature. Painting and sculpture were also compared with poetry, generally associated with the Trivium which was formed by grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Bandinelli was a writer and poet as well as an artist. He became a member of the literary Accademia Fiorentina in 1545.

Bandinelli points to a drawing representing Hercules victory over Cacus. The choice of a drawing as opposed to a piece of sculpture was undoubtedly intentional. It is significant that Bandinelli does not show himself as a sculptor with the "tools of the trade." Bandinelli's fine clothing and absence of tools disassociates him from the manual practice of the sculptor, while the reference to drawing associates Bandinelli with what was understood as the most intellectual element of artistic practice. Disegno, drawing or design, was the foundation of the Florentine artistic tradition. Vasari, Bandinelli's contemporary and rival, praised Bandinelli's mastery of disegno: "His disegno was praised by experts...." Vasari presents the following definition of disegno, which Vasari sees as the "visible expression and manifestation of the idea which exists in [the mind of the artist]":

Father of our three arts (architecture, sculpture, and painting), disegno proceeds from the intellect, drawing from many things a universal judgment similar to a form or idea of all the things of nature, which is most singular in its measures (...) [And] from this cognition is born a certain concept (...) such that something is formed in the mind and then expressed with the hands, which is called disegno. One could conclude that this disegno is none other than an apparent expression and declaration of the concept that evolves in the soul(...) When it has derived from [a universal] judgment an image of something, disegno [then] requires that the hand be trained through study and practice to draw and express (with pen, with silver-point, with charcoal or with chalk) whatever nature has created. For when the intellect puts forth concepts and judgments purged [of the accidents of the phenomenal world], the hands that have many years of practice make known the perfection and excellence of the arts along with the knowledge of the artist. |

More specifically disegno focuses on the mastery of the artist to represent the three dimensional form of the human body in two dimensions. Vasari in the following passage emphasizes the importance of the study of the figure as the foundation to art:

The best thing is to draw men and women from the nude and thus fix in the memory by constant exercise the muscles of the torso, back, legs, arms, and knees, with the bones underneath. Then one may be sure that, through much study, attitudes in any position can be drawn by help of the imagination without one's having the living forms in view [Anthony Blunt, Artistic Theory in Italy 1450-1660, p. 90] . |

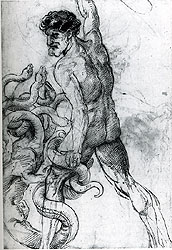

Artists were challenged to render figures in complex, turning poses and accurately render the skeletal and muscular structure of the body through the contour and modeling of the surfaces of the body. Michelangelo set the standard which all artists attempted to emulate. His mastery of disegno is well illustrated by his drawing for the Libyan Sybil of the Sistine Ceiling and a drawing of male nude.

Raphael

in his drawing of Hercules and the Hydra of about 1508 with its strong emphasis

on contour lines articulating a dramatically turning pose and the modelling

of the bulging muscles demonstrates the impact of Michelangelo on his work.

In learning from Michelangelo, Raphael is also rivalling him. In disegno, the

fundamental principle of all the arts in Florentine eyes, the artist demonstrated

his virtù through his invenzione which was understood

as "the solving of difficult problems and the treatment of new problems

achieved by a lively intelligence." Artists challenged themselves to

present the human body in complex poses. By doing this they overcame difficultà. The

fluid movement or grazia (grace) of these figures also speaks of

the artist's demonstration of sprezzatura, which is the apparently

effortless resolution of difficulty. Sprezzatura was identified

by Baldesar Castiglione in his Book of the Courtier as one of the

attributes of a refined courtier. He explicitly drew the parallel between

the manner of the courtier and the artist's ability to draw a seemingly effortless

line: "Often too in painting, a single line not laboured, a single brushstroke

easily drawn, so that it seems as if the hand moves unbidden to its aim according

to the painter's wish, without being guided by care or any skill, clearly

reveals the excellence of th craftsman, which every man appreciates according

to his capacity for judging." In

conceiving of his disegno shown

in his self-portrait in these terms, Bandinelli was claiming the heroic status

of the artist. As such his choice of subject matter of Hercules and Cacus

was undoubtedly intended to equate the labors of Hercules to that of the

Florentine artist. In both the painted drawing and his own pose with their

dramatic turning poses, Bandinelli displays his mastery of disegno.

Raphael

in his drawing of Hercules and the Hydra of about 1508 with its strong emphasis

on contour lines articulating a dramatically turning pose and the modelling

of the bulging muscles demonstrates the impact of Michelangelo on his work.

In learning from Michelangelo, Raphael is also rivalling him. In disegno, the

fundamental principle of all the arts in Florentine eyes, the artist demonstrated

his virtù through his invenzione which was understood

as "the solving of difficult problems and the treatment of new problems

achieved by a lively intelligence." Artists challenged themselves to

present the human body in complex poses. By doing this they overcame difficultà. The

fluid movement or grazia (grace) of these figures also speaks of

the artist's demonstration of sprezzatura, which is the apparently

effortless resolution of difficulty. Sprezzatura was identified

by Baldesar Castiglione in his Book of the Courtier as one of the

attributes of a refined courtier. He explicitly drew the parallel between

the manner of the courtier and the artist's ability to draw a seemingly effortless

line: "Often too in painting, a single line not laboured, a single brushstroke

easily drawn, so that it seems as if the hand moves unbidden to its aim according

to the painter's wish, without being guided by care or any skill, clearly

reveals the excellence of th craftsman, which every man appreciates according

to his capacity for judging." In

conceiving of his disegno shown

in his self-portrait in these terms, Bandinelli was claiming the heroic status

of the artist. As such his choice of subject matter of Hercules and Cacus

was undoubtedly intended to equate the labors of Hercules to that of the

Florentine artist. In both the painted drawing and his own pose with their

dramatic turning poses, Bandinelli displays his mastery of disegno.

The drawing of Hercules and Cacus is also a reference to Bandinelli's most famous public sculpture of the same subject made between 1525-34 for the exterior of the Palazzo Vecchio:

Comparison to the completed sculpture demonstrates that the painting presents a preliminary version of the sculptural group. The history of this commission teaches us about the Florentine conception of the artist. When Michelangelo made his David it was intended to be paired by a statue of Hercules by Leonardo da Vinci. The block for this Hercules figure was quarried in 1506. Leonardo's work on this project never progressed beyond preliminary drawings. Michelangelo had sought unsuccessfully to receive the commission to complete the pendant to his own David. Bandinelli received the commission to create the Hercules figure through his family's connection to the Medici family. The republican sentiments of many Florentines lead to the hatred of the Medici Dukes and by association of Bandinelli who was seen as a Medici propagandist. Michelangelo as well as his followers Giorgio Vasari and Benevenuto Cellini were very vocal in their attacks on Baccio and his works. Cellini directly attacked Baccio and lauded Michelangelo before his patron Duke Cosimo de Medici by reminding the Duke "that marble from which Bandinello made his Hercules and Cacus was quarried for the marvellous Michelangelo Buonarroti,

When Michelangelo made his David it was intended to be paired by a statue of Hercules by Leonardo da Vinci. The block for this Hercules figure was quarried in 1506. Leonardo's work on this project never progressed beyond preliminary drawings. Michelangelo had sought unsuccessfully to receive the commission to complete the pendant to his own David. Bandinelli received the commission to create the Hercules figure through his family's connection to the Medici family. The republican sentiments of many Florentines lead to the hatred of the Medici Dukes and by association of Bandinelli who was seen as a Medici propagandist. Michelangelo as well as his followers Giorgio Vasari and Benevenuto Cellini were very vocal in their attacks on Baccio and his works. Cellini directly attacked Baccio and lauded Michelangelo before his patron Duke Cosimo de Medici by reminding the Duke "that marble from which Bandinello made his Hercules and Cacus was quarried for the marvellous Michelangelo Buonarroti,  who had made for it a model of a Samson, four figures in all [...]: and your Bandinello got only two figures out of it." Rembering how we emphasized in our discussion of Michelangelo's David how it was seen as a major accomplishment and a testament to Michelangelo's ability to overcome difficultà how he was able to carve this figure out of this giant block that was understood to be imperfect. The strong similarities of the pose of Hercules with its open stance and positioning of the arms to the figure of St. George by Donatello demonstrate Bandinelli's knowledge of the work of the great fifteenth century precursor. The similarity of the Hercules to the Donatello is made more evident when it is remembered that the St. George originally had a sword in his right hand corresponding to the club held by Hercules. The apparent borrowing from Donatello was perhaps intended by Bandinelli to be a slight to Michelangelo. The turning motion of the Hercules challenges the frontality of Michelangelo's David. These details attest to the intense rivalries that existed among the Florentine artists.

who had made for it a model of a Samson, four figures in all [...]: and your Bandinello got only two figures out of it." Rembering how we emphasized in our discussion of Michelangelo's David how it was seen as a major accomplishment and a testament to Michelangelo's ability to overcome difficultà how he was able to carve this figure out of this giant block that was understood to be imperfect. The strong similarities of the pose of Hercules with its open stance and positioning of the arms to the figure of St. George by Donatello demonstrate Bandinelli's knowledge of the work of the great fifteenth century precursor. The similarity of the Hercules to the Donatello is made more evident when it is remembered that the St. George originally had a sword in his right hand corresponding to the club held by Hercules. The apparent borrowing from Donatello was perhaps intended by Bandinelli to be a slight to Michelangelo. The turning motion of the Hercules challenges the frontality of Michelangelo's David. These details attest to the intense rivalries that existed among the Florentine artists.

While the history of the Hercules commission testifies to the rivalry between Bandinelli and Michelangelo, the pose of Baccio's self portrait would be unthinkable without the precedents of the work of Michelangelo. The powerful pose with strong hands and the intensity of his eyes and long flowing beard calls to mind Michelangelo's prophets from the Sistine Chapel and the Moses he made for the Tomb of Julius II. The power and intensity of this divinely inspired figure can be seen to give visual form to the idea of terribilità.

Gaining Perspective

As a way of getting perspective on the transformations in the conceptions of the artist since the early fifteenth century, it is useful to compare the Bandinelli self-portrait to the predella of Nanni di Banco's Quattro Santi Coronati group that he did between c. 1408-![]() 13 for the niche of the guild of the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname (Guild of the Stone and Woodcutters) on the exterior of Or San Michele. The four figures in the niche represent Christian sculptures who were martyred for having refused to create a sculpture of Aesculapius for the Emperor Diocletian. The predella shows members of the guild busy at work on the products of the guild. Compare this relief to the Bandinelli self-portrait.

13 for the niche of the guild of the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname (Guild of the Stone and Woodcutters) on the exterior of Or San Michele. The four figures in the niche represent Christian sculptures who were martyred for having refused to create a sculpture of Aesculapius for the Emperor Diocletian. The predella shows members of the guild busy at work on the products of the guild. Compare this relief to the Bandinelli self-portrait.