Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200

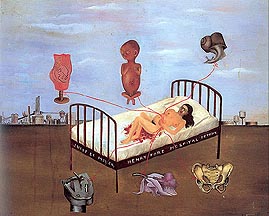

Frida Kahlo's Self-Representations and Questions of Identity

The art of Frida Kahlo has been the focus of great interest for critics and scholars in the last generation. This is dramatically manifested in the 2002 movie Frida starring Selma Hayek. While her work was generally ignored by scholars in the 1960s undoubtedly due to her pro-Communist stance, the rise of feminism and questions of identity in recent critical theory have led scholars to reevaluate her work. The following excerpt from John Tagg's Ground of Dispute (p. 20) suggest why Kahlo's work would gain recent critical acceptance:

| It was in 1984 that Adrienne Rich called for such a 'politics of location', beginning with 'the geography closest in --the body', more exactly, my body: my place to see from (and be seen), my place to ask my questions (and to listen), my point of multiple perspectives (and my part in the problem), my place of comparing, beginning to discern patterns, undoing bonds and building alliances. But if my body is a locus, it is not the centre of a discourse; and if it is located, it is at once 'a place in history' and a site of 'more than one identity'. In this sense, my body is never one place: it is always elsewhere, dispersed in meaning and differentiation, given over to the unequal exchanges of discipline and desire.... |

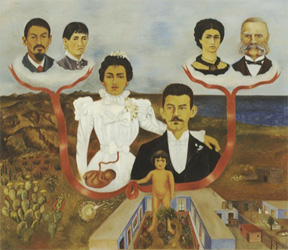

Kahlo's body and her cultural identity(ies) are central to an understanding of her work. Kahlo (1907-1954) was born in 1907 in the "Blue House" in Coyoacán, a quiet town in the outskirts of Mexico city. Her father Wilhelm Kahlo, was a Hungarian Jewish immigrant who arrived in Mexico in 1891 and married a Mexican native. He changed his first name to Guillermo and worked as a photographer specializing in architectural monuments of the pre-Hispanic and colonial eras. Soon after his first wife died in childbirth, Kahlo's father married Matilde Calderón, a mestiza, a Mexican of mixed European and American Indian ancestry, who was to become Frida's mother. Frida's awareness of herself as a mestiza is central an understanding of her work. Many of her works deal with this dialectic between her European and indigenous Mexican identities. This is illustrated by her 1939 painting The Two Fridas, with the Frida on the left wearing a white lace dress of the European tradition while the one on the right wears the traditional local dress of Tehuana:

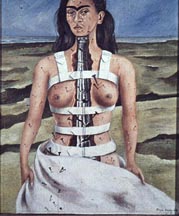

A tragic bus accident in 1925 when she was 18, left Frida with a fractured spine, a crushed pelvis, and broken foot. She was to remain partially handicapped and in pain for the rest of her life. This life-changing event set in motion the practice of faithfully recording the painful episodes of her life through her art. Many of her works focus on her pain and the multiple surgeries that she endured. The Broken Column of 1944 shows her wearing the backbrace that appears regularly in her paintings:

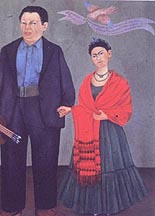

Kahlo married Diego Rivera (1886-1957), the great Meixcan muralist, in 1929. They had a complex relationship defined by mutual admiration, painful separations and reconciliations. Her identity as the wife of the "great artist" was another theme in her work:

Rivera was attracted to the patronage opportunities in the United States. Living in the United States for several year, Rivera and Kahlo socialized with such prominent American figures as Conger Goodyear, the Rockefellers, Henry Ford, and Clare Boothe Luce, often making the newspaper headlines. Although Kahlo and Rivera spent a number of years working in the United States, their connection with the life and culture of Mexico – their sense of Mexicanidad – remained absolute and was the defining element of their identities. A painting like Self Portait on the Border Between Mexico and the United States of 1932 reflects this dialect between her experience in the United States and her sense of Mexicanidad:

While working for the great American capitalists, Rivera and Kahlo were advocates of Marxism and Communism. When she died in 1954, her body lay in state in the Palace of the Arts in Mexico City. Her coffin was draped with a large flag bearing the Soviet hammer and sickle superimposed upon a star. A painting like My Dress Hangs There of 1933 reflects the tensions of her experience:

Janice Helland in her "Culture, Politics, and Identity in the Paintings of Frida Kahlo" (reprinted in The Expanding Discourse, pp. 396-407:

| In another painting from her United States sojourn, My Dress Hangs There, Kahlo scourges the United States with representations of the accoutrements of bourgeois life-style (a toilet, a telephone, and a sports trophy) and indicts its hypocrisy by wrapping a dollar sign around the cross of a church. Her appropriated photographs of Depression-era unemployment, which constitute the lower part of the pictgure, juxtapose "reality" with the "made-up" painting and thereby highlight the vulgar display of American wealth and well-being as opposed to the poverty and suffering of the lower classes. In the midst of this Kahlo places a pristine image: the Tehuana dress. This traditional costume of Zapotec women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is one of the few recurring indigenous representations in Kahlo's work that is not Aztec. Becauce Zapotec women represent and ideal of freedom and economic independence, their dress probably appealed to Kahlo. |

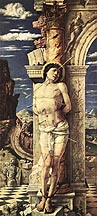

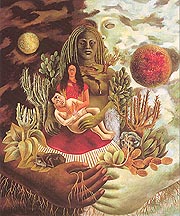

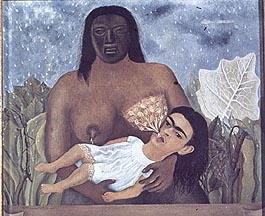

Kahlo's works thus represent a mixture of cultural and artistic traditions. The Pre-Columbian art of the Aztec is mixed with the traditional Mexican Catholic art, especially images of martyrdom and the Passion of Christ. Traditional religious imagery focused on the Instruments of the Passion and the wounds or Stigmata of Christ. Images of the suffering of Christ and the Saints surrounded the traditional Mexican Catholics in their spiritual life. The message taught by the Church was to learn to endure the pain and hardship and be prepared to suffer and sacrifice as Christ and his Martyrs did. Despite the intense pain undoubtedly the result of their torture, Christ and his Matryrs confront the faithful with their expressionless stares. Her Broken Column can be traced back through the Mexican Catholic art to its European sources in images like Andrea Mantegna's Saint Sebastian:

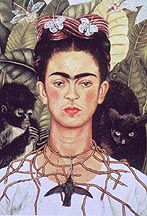

In Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, Kahlo mixes indigenous Aztec tradition with Christian imagery. The thorn necklace echoes Christ's Crown of Thorns while at the same echoes Aztec practices where priests performed self-mutilation with agave thorns and stingray spines. The dead hummingbird is sacred to the chief god of Tenochtitlan, Huitzilopichtli, the god of sun and of war. The fearful Aztec goddess Coatlicue wears a necklace of skulls:

Examine the works in the gallery below and identify the different cultural and artistic traditions included in the works. For further material on Kahlo see the links to other webpages below.

|

Gallery

of the Work of Frida Kahlo

|

|

|

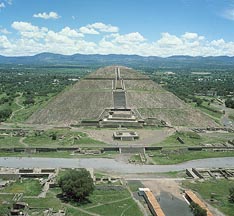

Pyramid of the Sun, c. 350-650 from Teotihuacán. |

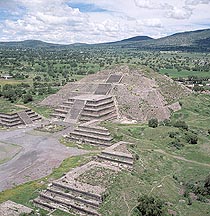

Pyramid of the Moon, c. 350-650 from Teotihuacán. |

Web Sites:

Artcyclopedia entry on Frida Kahlo.

Mesoamerican Cultures : a useful site for exploring the Pre-Columbian imagery in Kahlo's art.

Ancient Mesoamerican Civilizations: site developed by Kevin L. Callahan of the University of Minnesota.

Teotihuacán: City of the Gods:

Further Reading:

Gloria Anzalduá's Borderlands/La Frontera

Gloria Anzalduá's Borderlands/La Frontera (1987), although more recent and informed by contemporary critical theory, explores many of the same issues of cultural identity found in Kahlo's paintings. The following excerpts are from version of Anzaldúa's text that appeared in Ways of Reading, Third edition, David Bartholomae and Anthony Petrosky eds:

Coatlalopeuh, She Who Has Dominion over Serpents

/p. 26: ...My family, like most Chicanos, did not practice Roman Catholicism but a folk Catholicism with many pagan elements. La Virgen de Guadalupe's Indian name is Coatlalopeuh. She is the central deity connecting us to our Indian ancestry.

Coatlalopeuh

is descended from, or is an aspect of, earlier Mesoamerican fertility and

Earth goddesses.  The earliest is Coatlicue, or "Serpent Skirt."

She had a human skull or serpent for a head, a necklace of human hearts, a

skirt of twisted serpents, and taloned feet. As creator goddess, she was mother

of the celestial deities, and of Huitzilopochtli and his sister, Coyolxauhqui,

She with Golden Bells, Goddess of the Moon, who was decapitated by her brother.

Another aspect of Coatlicue is Tonantsi. The Totonacs, tired

of the Aztec human sacrifices to the male god, Huitzilopochtli, renewed

their reverence for Tonantsi who preferred the sacrifice of birds and

small animals.

The earliest is Coatlicue, or "Serpent Skirt."

She had a human skull or serpent for a head, a necklace of human hearts, a

skirt of twisted serpents, and taloned feet. As creator goddess, she was mother

of the celestial deities, and of Huitzilopochtli and his sister, Coyolxauhqui,

She with Golden Bells, Goddess of the Moon, who was decapitated by her brother.

Another aspect of Coatlicue is Tonantsi. The Totonacs, tired

of the Aztec human sacrifices to the male god, Huitzilopochtli, renewed

their reverence for Tonantsi who preferred the sacrifice of birds and

small animals.

The male-dominated Azteca-Mexica culture drove the powerful female/ p. 27:deities underground by giving them monstrous attributes and by substituting male deities in their place, thus splitting the female Self and the female deities. They divided her who had been complete, who possessed both upper (light) and underworld (dark) aspects. Coatlicue, the Serpent goddess, and her more sinister aspects, Tlazolteotl and Cihuacoatl, were "darkened" and disempowered much in the same manner as the Indian Kali.

Tonantsi --split from her dark guises, Coatlicue, Tlazolteotl, and Cihuacoatl-- became the good mother. The Nahuas, through ritual and prayer, sought to oblige Tonantsi to ensure their health and the growth of their crops. It was she who gave México the cactus plant to provide her people with milk and pulque. It was she who defended her children against the wrath of the Christian God by challenging God, her son, to produce mother's milk (as she had done) to prove that his benevolence equalled his disciplinary harshness.

After the Conquest, the Spaniards and their Church continues to split Tonantsi / Guadalupe. They desexed Guadalupe, taking Coatlalopeuh, the serpent / sexuality, out of her. They completed the split begun by the Nahuas by making la Virgen de Guadalupe / Virgen María into chaste virgins and Tlazolteotl / Coatlicue /la Chingada into putas; into the Beauties and the Beasts. They went even further; they made all Indian deities and religious practices the work of the devil....

/p. 30: Before the Aztecs became a militaristic, bureaucratic state where male predatory warfare and conquest were based on patrilineal nobility, the principle of balance opposition between the sexes existed. The people worshipped the Lord and Lady of Duality, Ometecuhtli and Omechihuatl. Before the change to male dominance, Coatlicue, the Lady of the Serpent Skirt, contained and balanced dualities of male and female, light and dark, life and death.

The changes that led to the loss of the balanced oppositions began when the Azteca, one of the twenty Toltec tribes, make the last pilgrimage from a place called Aztlán. The migration south began about the year A.D. 820. Three hundred years later the advance guard arrived near Tula, the capital of the declining Toltec empire. By the eleventh century, they had joined /p. 31: with the Chichimec tribe of Mexitin (afterwards called Mexica) into one religious and administrative organization within Aztlán, the Aztec territory. The Mexitin, with their tribal god Tetzauhteotl Huitzilopochtli (Magnificent Hummingbird on the Left), gained control of the religious system. (In some stories Huitzilopochtli killed his sister, the moon goddess Malinalxoch, who used her supernatural power over animals to control the tribe rather than wage war.)

Huitzilopochtli assigned the Azteca-Mexica the task of keeping the human race (the present cosmic age called the Fifth Sun, El Quinto Sol) alive. They were to guarantee the harmonious preservation of the human race by unifying all the people on earth into social, religious, and administrative organ. The Aztec people considered themselves in charge of regulating all earthly matters. Their instrument: controlled or regulated war to gain and exercise power.

After 100 years in the central plateau, the Azteca-Mexica went to Chapultepec, where they settled in 1248 (the present site of the park on the outskirts of Mexico City). There, in 1345, the Aztec-Mexica chose the site of their capital, Tenochtitlan. By 1428, they dominated the Central Mexican lake area.

The Aztec ruler, Itzcoatl, destroyed all the painted documents (books called codices) and rewrote a mythology that validated the wars of conquest and thus continued the shift from a tribe based on clans to one based on classes. From 1429 to 1440, the Aztecs, emerged as a militaristic state that preyed on neighboring tribes for tribute and captives....

Matrilineal descent characterized the Toltecs and perhaps early Aztex society. Women possessed property, and were curers as well as priestesses. According to the codices, women in former times had the supreme power in Tula, and in the beginning of the Aztec dynasty, the royal blood ran through the female line. A council of elders of the Calpul headed by a /p. 32: supreme leader, or tlactlo, called the father and mother of the people, governed the tribe. The supreme leader's vice-emperor occupied the position of "Snake Woman" or Cihuacoatl, a goddess....

Nevertheless, it took less than three centuries for Aztec society to change from the balanced duality of their earlier times and from the egalitarian traditions of a wandering tribe to those of a predatory state...

Coatl. In pre-Columbian America the most notable symbol was the serpent. The Olmecs associated womanhood with the Serpent's mouth which was guarded by rows of dangerous teeth, a sort of vagina dentate. They considered it the most sacred place on earth, a place of refuge, the creative womb from which all things were born and to which all things returned. Snake people had holes, entrances to the body of the Earth Serpent; they followed the Serpent's way, identified with the Serpent deity, with the /p. 33: mouth, both the eater and the eaten. The destiny of humankind is to be devoured by the Serpent.

Like Frida Kahlo, Gloria Anzaldúa bases her work on her mestiza identity, merging Anglo, European, Mexican, and Chicano identities. Andzaldúa advocates a mestiza consciousness where the borders between the different identities are broken down. In her words, "It is a consciousness of the Borderlands."

p. 50: These numerous possibilities leave la mestiza floundering in uncharted seas. In perceiving conflicting information and points of view, she is subject to a swamping of her psychological borders. She has discovered that she can't hold concepts or ideas in rigid boundaries. The borders and walls that are supposed to keep the undesirable ideas out are entrenched habits and patterns of behavior; these habits and patterns are the enemy within. Rigidity means death. Only by remaining flexible is she able to stretch the psyche horizontally and vertically. La mestiza constantly has to shift out of habitual formations; from convergent thinking, analytical reasoning that tends to use rationality to move towards a single goal (a Western mode), to divergent thinking, characterized by movement away from set patterns /p. 51: and goals and towards a more whole perspective, one that includes rather than excludes.

The new mestiza copes by developing a tolerance for contradictions, a tolerance for ambiguity. She learns to be an Indian in Mexican culture, to be Mexican from an Anglo point of view. She learns to juggle cultures. She has a plural personality, she operates in a pluralistic mode --nothing is thrust out, the good the bad and the ugly, nothing rejected, nothing abandoned. Not only does she sustain contradictions, she turns the ambivalence into something else....

This assembly is not one where severed or separated pieces merely come together. Nor is it a balancing of opposing powers. In attempting to work out a synthesis, the self has added a third element which is greater than the sum of its severed parts. That third element is a new consciousness -- a mestiza consciousness-- and though it is a source of intense pain, its energy comes from continual creative motion that keeps breaking down the unitary aspect of each new paradigm.

En unas pocas centurias, the future will belong to the mestiza. Because the future depends on the breaking down of paradigms, it depends on the straddling of two or more cultures. By creating a new mythos --that is, a change in the way we perceive reality, the way we see ourselves, and the ways we behave-- the mestiza creates a new consciousness.

The work of mestiza consciousness is to break down the subject-object duality that keeps her a prisoner and to show in the flesh and through the images in her work how duality is transcended. The answer to the problem between the white race adn the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could, in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war.