Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 212 Assignments | Carolingian Empire

Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel

Excerpt from Heinrich Fichtenau's Carolingian Empire, pp. 54-55: When the palace chapel at Aix-la-Chapelle was built, it was planned as a double church. On the ground level the servants attended divine service at the altar of Mary. The magnates assembled in the choirs of the octagon around the king's seat....

From that seat one could look down upon the altar of Mary and, looking across the centre of the octagon, one could see the altar of the Saviour in the eastern choir. Master and servants were strictly separated; so much so that even Mary, the Lord's servant, had to have her altar below that of her Son. One might even wonder whether it was more than accident that her altar was below the royal seat. We must avoid rash conclusions because, although the altar of the Saviour and the royal seat were on the same level, the one was in the east and the other in the west end of the building. In the symbolism of ecclesiastical architecture the contrast between east and west plays a decisive role, by separating the sacred east with the space for the altar from the western part, built like a stronghold and reserved for the faithful.

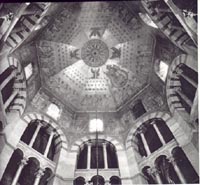

Above the places reserved for the people and the king there was the sphere reserved for God. The cupola which rose above the octagon is no longer in existence and we can form an impression of what it looked like only by reconstruction....

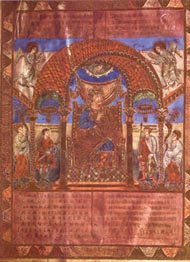

The inside of the cupola was covered with golden mosaics illustrating the fourth chapter of the Apocalypse. Christ was shown enthroned among the twenty-four elders and among the four symbols of the evangelists, the lion, the ox, the man, and the eagle. This was the first important representation of maiestas [majesty] on German soil. During the Romanesque period such representations were to become the dominant themes of pictorial and plastic art. The heavenly splendour of this sphere outshone the spectacle of earthly pomp offered on the middle floor by the gilded bronze railings and the polished pillars. From the ground floor the servants and the common people looked up to all this splendour, while they themselves stood among the plain pillars of ordinary stone.... The palace chapel of Aix-la-Chapelle was the reflection of the great cosmic order of government.

|

|

The different spheres of the cosmic order, though clearly distinct, showed a similarity in structure. Any occurrence in one of the spheres produced an effect in all the others. If the ruler was angry there appeared threatening signs in the sky. Comets, downpours of blood or of stones, storms and floods signified discord, dissension and disturbance of the cosmic order. The devil was anxious to promote confusion in nature as well as in the hearts of men by inciting servants against their masters and the masters against the ruler. On the other hand, if everybody willingly accepted their status and the undisturbed exercise of royal authority under God and over men, the result would be victory for the royal armies, calm winds, fertility of both earth and women, and the health of the whole people. Such conditions meant that the world was well balanced and in a state of pax [peace]. The king's most important task was to achieve such peace and to maintain it.

This task had been assigned to him by Christ. The king was the vice-regent of the earthly sphere which he ruled on behalf of the King of the whole creation which included both the upper and nether regions. An earthly king was therefore no absolute ruler. He was the lieutenant of a greater power to whom he had to render the strictest account. He was supposed to appear, on the day of the Last Judgment, as a faithful servant and steward, Towards Christ he occupied the same position of service as the officials of his own realm occupied towards himself. The church, far from protesting against the idea that the heavenly King had set a special task for the earthly king, emphasized it through unction. An attack upon the ruler was an attack upon a person removed from the sphere of everyday life by a heavenly mandate and invested with a 'taboo'....

The ruler was appointed by the grace of God, by the favour of the real, heavenly Emperor, to govern his Christian subjects as his lieutenant. The right to judge and the power of the 'ban' formed the essence and the mark of all government. This power meant the right and duty to punish evil-doers, to issue orders to the law-abiding and to summon them to military service in the Christian army in the cause of order against all devilish attempts to sow dissension. We may well ask at this point whether the earthly emperor or king had received, from the hand of the heavenly ruler, not only his administrative, judicial, and military authority, but also the power of the sacred mysteries. Was the earthly ruler, in the proper sense of the words, a rex et sacerdos, king and priest at the same time?

People were wont to compare Charles, as well as his predecessors and his successors, with David and Solomon. But according to the Old Testament, neither David nor Solomon were priest-kings. In the Old Testament Melchizedek was the only priest-king; and when the Byzantines wanted to justify the formula for the priest-kingship, they cited him. This formula and the conception it implied had already, during the eighth century, been decisively rejected by the church. The pope actually forbade the Byzantine emperors to use that title, and subsequent conciliar decrees laid down that it was reserved for Christ alone....