Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 212 Assignments

The Threshold

Excerpt from the chapter entitled "The Threshold" from Georges Duby, The Age of the Cathedrals:

| "God cannot be seen directly. The contemplative life that begins on earth will only be perfect once God has been seen face to face. When a gentle, simple soul has been elevated to speculative heights and when, breaking the ties of the flesh, it has contemplated what lies in heaven, it cannot remain long above itself, for the weight of the flesh pulls it back down to earth. Though it is struck by the immensity of the light on high, it is quickly reminded of its own nature; yet the little it has been able to taste of the divine sweetness is of utmost benefit to it, and soon thereafter, inspired by great love, it hastens to resume its upward flight." |

These were the tensions in monastic spirituality. Eleventh-century man was confined within close limits by his senses and the pitiable means available to him. The spiritual life aspired through experiencing perfect brotherhood, through the liturgy, through music, and lastly through works of art, to transcend those limits. It was on continuous effort to outreach sense perception and intellectual understanding, to glimpse what would be revealed to mankind, entire and resurrected, when the world's last day came, to fathom that other part of the universe whose attractions and powers could be guessed but not seen. A yearning for God --in other words, a yearning for mystery.

No matter how scholarly they were, the men of the Church could not intellectualize their faith. Their equipment for reasoning proved to be as inadequate as the wooden plows that farmers dragged over parcels of cleared land. They did not read Greek, and the wisdom of the antique philosophers was lost to them once and for all. The handful of scientific treatised that a moribund Rome, indifferent to any genuined science, had bequeathed to them were not enough to liberate their thinking from the patterns that governed peasant wisdom. Like their worldly brothers, the /p. 76 terrified hunters and knights who ventured into unknown thickets and the ambushes of war, the men of God were on the alert....

By means of collective rites, of participation -- through gestures-- in the mysteries, men could rise above their own natures and, as Rupert of Deutz expressed it, become prophets themselves, that is, heralds of God. Among the instruments used to grasp the ungraspable, music and liturgy were foremost. No one as yet included reasoning among them. The tool universally used was exegesis, encompassing all the types of mental inquiry. Signs issued from the invisible God; they were as mysterious as he was himself. It was vital to decipher those messages, and all the teaching methods had aimed for that goal ever since the rebirth of study in the Carolingian monasteries.

The Benedictine monk Raban Maur, "preceptor of Germania" and abbot of Fulda in the second quarter of the ninth century, was one of the first to define the approach. "It has occurred to me," he said, "to compose a short treatise which would deal not only with the nature of things and the property of words but also with their mystical meaning." Words and nature were the two fields accessible to the human mind in which God consented to appear. Accordingly, every monk pored over the Scriptures, and the teaching of grammar prepared him to progress from the oral to the spiritual and so, by degrees, to penetrate the meaning of every syllable. He also pored over the created world in search of analogies whose interlinking might lead him toward the truth. "Through the countless differences which God, Creator of all things, established between the faces and forms of his creatures, he intended to enable the soul of a scholarly man to rise, by means of what the eyes see and the mind grasps, to a simple knowledge of divinity." And Raoul Glaber added: "These indubitable connections between things preach God to us in a way that is evident, beautiful, and silent all at the same time; for whereas each thing, with an immutable movement, presents the other in itself by proclaiming the principle from which it proceeds, it needs to rest on that principle anew."

Such was the methodological itinerary. Since God created the universe that the human sense perceived, there remained a substantive identity between the Almighty and his creature -- or at least a very close union, the universitas mentioned by Johannes Scotus Erigena. Thus it was possible to discern God by, in the words of Saint Paul, gradually moving ahead per visibilia ad invisibilia [through the visible to the invisible] /p. 77: Creation, as a mute and motionless predication, embodied the richest lesson in the divine pedagogy. But just as one acquired greater understanding of the Scriptures by bringing out the correspondences between the words, the verses, and the various passages of the Old Testament and the New, just so it was important to discover relationships, harmonies --in short, a certain order amid the diversity of shapes and faces to be found in the visible universe. As William of Conches and Geroh of Reichersberg were later to put it, the world was "an orderly collection of creatures." It was quasi magnum citaram, "like a great zither." What man called art existed for one purpose: to make the harmonic structure of the world visible, to arrange a certain number of signs in exactly the right places. Art gave substance to the fruits of the contemplative life and transposed them into simple forms so as to make them perceivable by persons having just begun their initiation. Art was a discourse on God, as were liturgy and music. Like them, art aimed to prune and thin out the undergrowth and abstract the fundamental values buried in the dense core of nature and the Scriptures. Art revealed the inner framework of the orderly edifice called creation. To that end, art relied on certain texts containing the divine words, on the images which those words aroused, and on the numbers that marked off the cadences of the universe. Like both music and the liturgy, art used several means. Symbolism was one; the unexpected juxtaposition of conflcting values was also a means because, by striking one another, they caused truth to leap forth; and the rhythms through which the world breathed in unision with the divine respiration were yet another means. A monument, an example of the goldsmith's art, or a piece of sculpture constituted a gloss of the world, an explanation of it by virtue of their structures, the relative positions of the various elements composing them, the numerical relations maintained between those elements , and the patterns they made visible. Under the effects of its gradual action, which, between 980 and 1130, accompanied the emergence of polyphonic music and scholastic meditation, art offered a clue to the mystery. Art enabled man to grasp the substantive reality of the universe instantaneously, more perfectly than through reading and the mere seeing of things, more profoundly than through reasoning....

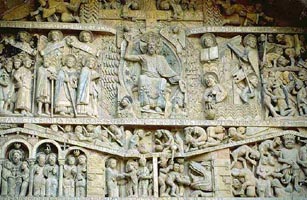

/p. 78: The new representation

type of sculpture on a monumental scale that appeared after 1100 was available

to the gathering throngs  of

believers as a teaching instrument. Some of the greatest examples of Romanesque

sculpture, placed at the threshold of abbey churches or the crossroads of the

principal pilgrimage itineraries, were very obviously designed for the edification

of the masses and therefore used a visual terminology that would be understandable

by all. The tympanum of Conques is one example....

of

believers as a teaching instrument. Some of the greatest examples of Romanesque

sculpture, placed at the threshold of abbey churches or the crossroads of the

principal pilgrimage itineraries, were very obviously designed for the edification

of the masses and therefore used a visual terminology that would be understandable

by all. The tympanum of Conques is one example....

For the universe did not stand still. It moved with God's own movement. Every spiritual experience was lived as a forward thrust, a progress, wed and guided at the same time by music and liturgy; and although architecture, sculpture, and painting were immobile by nature, they too had a mission to convey the universal movement, which in fact appeared twofold. To begin with, it was circular. The rhythms of the cosmos, the stars in their courses, the turning of day into night and season into season, and all types of biological growth followed cyclical patterns, and their periodic repetitions had to be taken as signs of eternity.

That was why in the Benedictine monasteries divine service --to which, according to the Rule, "nothing should be preferred"-- took place in accordance with two concentric circles. The first one was the one described each day by the singing of psalms. While it was still dark, the bell awoke the monks for the nocturnal rites. Then came lauds, a celebration of God offered at the first light of dawn, followed by prime, simultaneous with the rising sun. During the daytime hours, when the monks had to go about various occupation, just like other men, the offices of terce, sext, and nones were briefter; but prayer came into its own again as the night hours approached. At compline the brethern were reunited, and, as they sang together, found courage to face the dark.

The other cycle was the yearly one centered on Easter. One of the main tasks of both the sacristan and the cantor, who were responsible for the liturgical arrangements, was to work out the calendar each year, assign the various texts to be read, and plan the service so as to take exceptional celebrations into account. Hence a life of prayer implied the uninterrupted experience of cosmic time. By submitting to its circular rhythms and avoiding any accident that might upset them, the monastic community was /p. 79: already living eternity. It had genuinely overcome death, for the reiteration of daily and yearly prayers wiped out all trace of personal destiny, all awareness of growth and decline. Hence the symbol of the sidereal rhythms was the most important of the figures placed in the cloister and in books for purposes of guiding their beholder's meditation. Yet from the very instant when God created the world, he had stepped outside the eternal in order to establish his creature --and himself-- in time and in a destiny that was a straight line. And from that instant everything --man's progress, the progress of history itself-- was oriented, and religous monuments also had to be oriented, turned towards a specific point in space, if they were to interpret the divine intentions faithfully....

Writing history was one [the monks] specific functions. The monks chronicled their own times and recorded past events. They did so for several reasons. First of all, out of respect for a tradtion that the authors of antiquity had made illustrious.... But in addition the taste for historic accounts was in harmony with the ultimate purpose of monastic culture. After all, what was history if not one way of taking inventory of creation? History offered an image of man; in other words, an image of God. Oderic Vital, a Benedictine monk who was one of the best historians of his day, proclaimed: "History must be sung like a hymn in praise of the Creator, the just Governor of all things." Since history was a song of glory, it too fitted into the liturgy. And finally, history made it easier to follow mankind as it moved through the web of time, toward salvation, to recognize the several stages of its progress and discern how it was oriented. History opened out onto a prospect. It helped men to choose the right path, swim in the mainstream, and more surely reach port. From the origins of the world up to its end, one continuous /p. 80: procession appeared. The Scriptures, which were no different from a history, described it as a gradual ascension in three phases. The New Testament -- the second phase-- had smoothed out the rough spots that remained in humankind during the first phase, prior to the Incarnation. But compared to what he would become after the Second Coming, man was in exactly the same situation as the just men had been in, under the old law, in relation to the apostles. The world was growing older; the end of time could not be far away. Eleventh-century man lived in expectation of it. His sense of human history had to prepare him for that transition. It was the duty of all men who prayed, particularly the monks, to show --and smooth-- the way. The processions to and within the abbey churches were symbolic realizations of history. They completed the last phase as they mimed the entry into the Kingdom of Heaven. The goal of all monastic meditation and all monastic art was rend the veil and contemplate what lay beyond the open sky.

Since this was so, it became

less essential to observe visible nature. In fact, man had to leave it behind,

for it was in the Scriptures that he could discover what prefigured the Revelation.

Because eleventh-century Christianity, guided by its monks, insisted on depicting

what would soon take place before its eyes, and because it considered human

history an accidental, subordinate development, it did not scrutinize the Synoptic

Gospels or the Acts of the Apostles as closely as it did the Old Testament or

the Book of Revelation. Scenes from the life of Jesus did not often appear in

the figurative art of the times [In cases where they do appear like the Incarnation cycles at Moissac and Vézelay,

the emphasis is less on the narrative of the particular stories but on seeing

these scenes as theophanies and thus prefigurations of the final theophany at

the end of time.] ... Accordingly, eleventh-century sacred art concentrated

on condensing the teachings of the Gospel into a handful of signs. It turned

them into pillars of fire, like the one Jehovah used to guide his people toward

the Promised Land. None of these images showed Jesus as a brother. Instead he

was the master, the one who judges from on high, the Lord

[In cases where they do appear like the Incarnation cycles at Moissac and Vézelay,

the emphasis is less on the narrative of the particular stories but on seeing

these scenes as theophanies and thus prefigurations of the final theophany at

the end of time.] ... Accordingly, eleventh-century sacred art concentrated

on condensing the teachings of the Gospel into a handful of signs. It turned

them into pillars of fire, like the one Jehovah used to guide his people toward

the Promised Land. None of these images showed Jesus as a brother. Instead he

was the master, the one who judges from on high, the Lord  [,and

the one who does battle with the devil]. Against the golden background of the

pericopes the painters installed the apostles --outside of time, remote from

/p. 81: unpredictable nature, far from mankind. Who in those days woulc have

imagined Saint James or Saint Paul --those overwhelmingly powerful beings whose

tombs were the site of so many miracles, and who hurled lightning and intolerable

skin inflammations at those who contemned their rights --as fishermen and paupers?

How could the Christianity of the year 1000, prostrate before its reliquaries,

have dared to emphasize Christ's human traits? The Roman apostles lived in an

invisible universe -- that of the Christ resurrected at Easter, who forbade

the holy women to touch his body, that Jesus rising from the earth on Ascension

day, that of the Almighty entrhoned in the apse at Cluny or Tahull.

[,and

the one who does battle with the devil]. Against the golden background of the

pericopes the painters installed the apostles --outside of time, remote from

/p. 81: unpredictable nature, far from mankind. Who in those days woulc have

imagined Saint James or Saint Paul --those overwhelmingly powerful beings whose

tombs were the site of so many miracles, and who hurled lightning and intolerable

skin inflammations at those who contemned their rights --as fishermen and paupers?

How could the Christianity of the year 1000, prostrate before its reliquaries,

have dared to emphasize Christ's human traits? The Roman apostles lived in an

invisible universe -- that of the Christ resurrected at Easter, who forbade

the holy women to touch his body, that Jesus rising from the earth on Ascension

day, that of the Almighty entrhoned in the apse at Cluny or Tahull.

Neither the Christ of Cluny nor the Christ of Tahull was derived from the Gospels. They came straight from the Book of Revelation --from the dazzling heart of light. No other portion of the Scriptures offers more details about the structures of the world to come or any more exalting description of "the holy Jerusalem [whose] light was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal.... And the city had no need of the sun, neither of the moon, to shine in it: for the Glory of God did lighten it, and the Lamb is the light therof" [Rev. 21: 11, 23]. The cloisters, the religious meditated constantly on these strange words; they were commented upon, repeated, illustrated. What Saint John's vision showed was a magnificent, transfigured universe, but one that was not really different from the visible universe. For heaven and earth were arranged in very similar ways and closely related at the bosom of the divine harmony. As bishop Adalbero noted:

| This mighty Jerusalem is simply, it seems to me, a vision of peace. The King of Kings does govern it, the Lord does reign over it. Though it be divided into parts, nonetheless it is a whole. Not one of its gleaming gates is divided by the slightest length of metal. Its walls have no stones; its stones, no walls. Its stones are living stones; the gold paving its courtyards is living gold. It sparkles and gleams, more resplendent than molten gold. It is constituted at one and the same time by a citizenry of angels, who reign over the city, and the throng of men, who aspire to do so. |

The city of God and the earthly City communicated....

/p. 82: The art of the eleventh century, reflected men's hopes. The visible universe was narrow, restive, transitory, and decaying. The type of Christianity preached and practiced by the medieval Church sought to free the people from it. It followed that its art did not attempt to render palpable reality. But at the same time it was not abstract art, for the essential concordances made nature a faithful reflection of what was beyond nature. While an artist drew his inspiration from the forms found in nature, he also refined them and sifted through them so as to make them worthy of the glory of the Second Coming. He strove to find equivalents for the gleams of light glimpsed through mystic contemplation, to depict the absolute. And this aim fit in neatly with the monasteries' missions. It was there that works of art as such had begun to appear. The function of a monastery was not only to offer up to God the public and unceasing praises that were due him, but also to prepare men as a whole for the Resurrection. The monks were in the vanquard. They had already left the temporal world behind; an enclosing wall separated them from it. As abstinence of various kinds had already purified them, they had covered half the distance, and were toiling up the mountain whence one could see, through the mist, the marvels of the land of Canaan. It was as if the monks' desire for God sucked up every aspect of their art.

| Who shall give us wings like those of the dove so that we may then fly through all the kingdoms of the world and enter within the southern sky? Who shall lead us into the city of the great King, so that we noe read on the written page, what we perceive as riddles as if in a mirror, we shall then see by the grace of God, close by God in his presence, and shall rejoice over it? |

Perhaps study would make this possible; surely music and liturgy would, and art along with them.

| Let us lift up our hearts to them as well as our hands, let us transcend all transitory things. Let our eyes shed tears without end amid the joys that are promised to us. Let us rejoice over what has already been wrought among the faithful, for but yesterday they were fighting for Christ, and today thei reign with him. Let us rejoice over what we have been told, in truth: we shall enter the land of the living. |

This lyrical passage by an anonymous disciple of John of Fécamp indicates the vocation of sacred art: it must do all in its power to break the chains. The door to the monks' church opens onto the mystery of God.

At the entrance to each place of worship heaven did in fact open up. As a result of liturgical innovations, certain funerary ceremonies took place in the /p. 83: narthex, as did the special rites devoted to the Savior. This was where scenes illustrating the Apocalypse were placed so as to initiate the people into the mysteries....

But before the light could stream out from the Lamb, the four angels that guard the four winds of the earth would blow their trumpets and everything would be destroyed. Therefore any man, living or dead, who entered the church must first wipe out the germs of corruption within himself and strip himself of everything --weapons, wealth, relatives, even his will power-- just as the monks did when they took their vows. Then he would be fit to fall in with the great procession.

| And the nations of them which are saved shall walk in the light of it: and the kings of the earth do bring their glory and honor into it. And of the gates of it shall not be shut at all by day: for there shall be no night there. And they shall bring the glory and honor of the nations into it. And here shall in no wise enter into anything that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie; but they which are written in the Lamb's book of life [Revelation 21: 24-27] |

Romanesque art was created by a handful of men whose spiritual ascension carried them toward this mirage. For the sake of creating its image they gathered together the most marvelous things they could find: gold and lapis lazuli and the strange perfumes which the merchant caravans brought back in tiny quantities from the East. One day they decided to carve their vision in stone....

/p. 84: The door opening onto the unknowable and onto glory was Jesus:; he said it himself. In the course of the eleventh century an idea slowly made its way to the surface: the terrifying God whose throne, above the door at Moissac, towered over a throng of judges, the God who vented his wrath by visiting plagues and famine on mankind, along with war and the unknown looters who had poured out of the remoteness of Asia, the God whose return was eagerly awaited, was none other than the Son, that is, man himself. Gradually, dimly, the notion of incarnation gained ground.