Our modern museums with collections of medieval art are full of costly objects made of gold, silver, decorated with precious gems, ivory panels, and even antique cameos. These objects were not seen as simply beautiful and costly physical objects, but were seen as central objects in the liturgy of the Church. This Webpage is intended to help us appreciate the role and power of these objects in Medieval life.

These objects were housed in the treasuries of churches. The power of the church was clearly reflected in the holdings of its treasury. One of the richest Church treasuries was that housed at the Abbey Church of St Denis just outside of Paris. In 1706, Dom Michel Félibien (Histoire de l'Abbaye Royale de Saint-Denys en France) produced a series of engravings that present a visual inventory of the rich collection of the treasury of St. Denis. Alison Stones, in a work in progress, has provided an extremely useful study of these illustrations and the treasury itself at her website dedicated to Medieval Art and Architecture (click on the St. Denis link ). Since the treasury was dispersed or destroyed during the French Revolution, these illustrations provide us with critical documentation as to the original holdings. These images can be compared with Abbot Suger's De Administratione which documents the monastery during his tenure as abbot in the middle of the twelfth century. A fifteenth century painting of the Mass of St Gilles, depicting the great Golden Cross and the Altar Frontal of Charles the Bald is another critical document in the reconstruction of the treasury of St Denis.

The following engraving from Félibien's series can give an idea of the nature of holdings of a church treasury:

Prominently in the center is a reliquary of St Benedict, the founder of the Benedictine order (in a future class we will study the medieval cult of the relics). To the left is the Cross of St Eloi perhaps given to the monastery by Charles the Bald. To the right of the St Benedict is the so-called Screen of Charlemagne. At the the bottom left corner appears a book that has been identified as the Pontifical used in the Coronations of the French Kings. What were believed to be the sword and spurs of Charlemagne appear on the left wall of the engraving. The crown of Charlemagne appears at the lower right. Among the other objects is the so-called eagle of Suger. This last object is preserved today in the Louvre:

Suger transformed this Roman porphyry vase into an eagle. Suger in his de Administratione presents the following account of this object:

Hanging from the back wall between the reliquary of St Benedict and the Screen of Charlemagne is an object believed to be the cup of Solomon, while the bowl of the cup just to the left of the crown of Charlemagne has been attributed to the Ptolemies, the Hellenistic rulers of Egypt. This sardonyx bowl was then given a metalwork setting and donated to the abbey by Charles III (Charles the Simple, Charlemagne, or Charles the Bald).

This is just a part of the collection, but it clearly attests to the authority of the monastery with the associations believed to go back to King Solomon, the Ptolemies, Roman Emperors, St. Benedict, and Charlemagne. In effect this collection presents a conspectus of ancient and early medieval history.

Another object from the treasury of St Denis that is still extant is the so-called Suger Chalice currently preserved in the National Gallery of Art collection in Washington:

The sardonyx bowl dates from the 2nd or 1st centuries B.C. and was mounted in the present metalwork form by Suger. Suger presents the following description of the cup:

Like many other monuments of the medieval church treasuries, this object combines elements from diverse periods. This challenges our modern assumptions of artistic creation. We also need to examine how an object like this would be understood in the celebration of the liturgy.

During the later Middle Ages and the early Renaissance a very popular theme was the Mass of St. Gregory. This legend tells the story of Pope Gregory the Great and how during the celebration of the Mass at St. Peter's a Roman matron question that the Host is transformed into the body of Christ. Images like Dürer's 1511 print of the subject were intended to answer the doubts being raised about the nature of the Sacrament.

In this print Dürer effectively represents

the central reality of the Mass. The divisions between physical

and spiritual reality have been broken down. Christ as the Man

of Sorrows surrounded by the instruments of His Passion appears

powerfully alive. The altar cross has become the wood of the True

Cross, and the altar table has become the sepulchrum domini

(or the sepulcher of Christ). Significantly except for Gregory

the Great and the Angels above, we are the only ones who see the

True Presence of Christ. We, in effect, become the sceptical Roman

matron who becomes convinced by the miraculous presence of Christ.

The attention of the deacon assisting Gregory at the altar is

directed to the sacrament on the altar, acolytes on the right

attend to a thurible, while Cardinals and Bishops in the background

are apparently oblivious to the mystery occuring before them.

The group is dominated by the physical symbols of ecclesiastical

authority including the Papal crown and the bishop's crozier.

Through these details Dürer is asking us to transcend the

physical to see the spiritual reality. Dürer in this print

visualizes what Gregory the Great himself articulates in his Dialogues:

"...what right believing Christian can doubt that in the

very hour of the sacrifice, at the words of the Priest, the heavens

opened, and the quires of Angels are present in that mystery of

Jesus Christ; that high things are accomplished with low, and

earthly joined to heavenly, and that one thing is made of visible

and invisible...."

Following Dürer's lead, when we look at the lavish liturgical objects in collections of medieval art, we should see how these objects lead us from the visible to the invisible reality. A similar point can be made by examining facing pages from an eleventh century manuscript from Regensburg, the Uta Codex:

|

The miniature on the right shows St Erhard celebrating Mass, while at the top right corner of the miniature we see the Abbess Uta, the original owner of the manuscript, looking over to the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God). A verse above the Lamb states : "Lamb of God, you who take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us [+Agnus Dei+ Qui tollis peccata mundi misere[re] n[os]tri]." The positioning of the Lamb in relationship to the canopy above the head of St. Erhard presents a nice parallel to the chancel dome of San Vitale. The Agnus Dei is the allegorical representation of Christ's sacrifice commemorated in the Mass. The eucharistic symbolism is continued in an inscription along the underside of the canopy which reads: "Jesus Christ the true bread from heaven [Iesus Christus verus panis veniens de celis]. A second inscription along the underside of the canopy continues this theme: "He nourishes the Church with his body through faith on earth Who nourishes the angels in the heavens through his form [Hic pascit aec[c]lesiam corpore suo p[er] fidem in terris Qui p[er] specie[m] suam a[n]gelos pascit i[n] celis]."

Texts integrated into the miniature indicate the image can be understood as an allegory of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Written in Greek capitals, the word IHPAPXHIA, "hierarchy" ,appears on the band between the shoulders of St. Erhard. Extending from this diagonally appear the words sacer principatus, "holy supremacy / leadership." This inscription is apparently based on the Neo-Platonic text entitled The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy writtend by the Pseudo-Dionysius. In this text, the bishop is understood as the "hierarch" or pinnacle of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. In this function, the bishop best approximates the divine on earth. The words ordo s[ae]c[u]lor[um] appear along the vertical band bisecting Erhard's body. This band links three medallions bearing from bottom to top the inscriptions: umbra legis [shadow of the law], corp[us] ecl[es]i[ae] (the body of the Church), and lux aetern[a]e vit[ae] [light of eternal life]. This "order of the ages" refers to the different stages in the Christian plan of history: the Old Testament era of the Law of Moses, the era of the Church beginning with the life of Christ, and the fulfillment of the Christian plan with the era of eternal life. The movement from lowest to highest from shadow to body to light reflects the Neo-Platonic hierarchy from the physical to the divine.

St Erhard with his outstretched hands looks to his right past the liturgical objects on the altar to the facing page of Christ on the Cross. It is significant that Erhard's eyes pass through the liturgical objects to the Crucifixion. He is thus led by these visible signs to the spiritual reality. The saint's orant gesture makes the point of the identification of the priest with Christ during the celebration of the Mass. Bishop Durandus writes in the twelfth century: "The celebrant therefore, representing this [crucifixion] while speaking of the blessed Passion, extends his hands in the manner of a cross, to represent the extension of the body and hands of Christ on the Cross."

Closer examination of the altar in front of St Erhard has led to the identification of the actual objects represented here:

On the altar appears the Ciborium of King Arnulf:

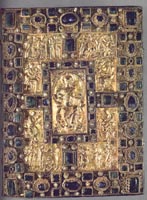

This ciborium, an object intended to house the sacrament, was apparently made about 870 for Charles the Bald. The ciborium was presented by King Odo or Charles the Simple to King Arnulf in about 896. Arnulf in turn gave it to the monastery of St Emmeram at Regensburg. The book on the altar in the Uta Codex miniature has been identified as the Codex Aureus of St Emmeram:

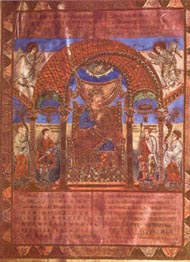

|

|

This Gospel manuscript closely parallels the ciborium. It was made for the Charles the Bald at his palace school about 870 and then given to Arnulf, who in turn gave it to St Emmeram. The book cover is closely related to the now lost altar frontal given by Charles the Bald to St. Denis. At the center of the cover appears Christ in Majesty seated on the globe of the world and holding on his knee a book inscribed with the words "I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No man cometh to the Father, but by me (John 14:6)." The inclusion of this inscription again identifies the Gospel Book with Christ. The verse makes equal sense if we read the speaker as Christ or as the Gospel Book.

Texts integrated into the miniature indicate the image should be understood as an allegory of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Following the Neo-Platonic thought which was revived by the Carolingians, where the world is understood as a hierarchic system moving from the lower, physical forms to the divine forms and the oneness of God, the liturgical objects, St Erhard, and the deacon symbolize three different degrees of access to God. These liturgical objects are thus important physical objects, intrinsically costly, and venerable due to their links back to Carolingian imperial power, and they play a central role in the mystery of the liturgy where one needs to go through these immediate physical objects to the spiritual reality beyond.

The miniature of the Crucifixion which faces the image of St. Erhard emphasis the triumph of the Cross. Christ is represented wearing a gold crown and clothes of imperial purple suggesting Christ's identity as Priest-King. The texts accompanying the facing Crucifixion miniature point to the central role the Cross plays in the plan of Salvation. The inscription around the oval or mandorla containing Christ reads: "By the stronghold of the cross, Erebus [hell], the cosmos, death and the devil, These things Christ, the omnipotent knowledge of the Father, conquered [Arce crucis herbu[m] cosmu[m] loetu[m] q[ue] diablu[m] H[a]ec patris om[ni]p[oten]s vicit sapientia XPC [Christus]]." The proportions of the Cross are related to the order of the macrocosm. Through the sacraments celebrated with these liturgical objects we are led to Eternal Life on the left hand side of the Cross. Without them we are subject to Death on the right side of the miniature.

Review Linked Pages: