Mosaics of San Vitale in Ravenna

The Chancel of San Vitale |

|

Mosaics of San Vitale in Ravenna

The Chancel of San Vitale |

|

The mosaic decoration in the sanctuary of San Vitale is undoubtedly one of the most important monuments of medieval art that has come down to us. It represents one of the most complete programs of mosaics still extant, and it was produced during extremely interesting historical circumstances.

Barberini Ivory (details), mid 6th century.

Coin commemorating Justinian's reconquests of Africa, c. 535

Procopius, historian and biographer of Justinian, presents in his On Building the following summary of the Emperor's accomplishments:

| In our own age there has been born the Emperor Justinian, who, taking over the State when it was harassed by disorder, has not only made it greater in extent, but also much more illustrious, by expelling from it those barbarians who had from of old pressed hard upon it, as I have made clear in detail in the Books on the Wars. Indeed they say that Themistocles, the son of Neocles, once boastfully said that he did not lack the ability to make a small state large. But this Sovereign does not lack the skill to produce completely transformed states — witness the way he has already added to the Roman domain many states which in his own times had belonged to others, and has created countless cities which did not exist before. And finding that the belief in God was, before his time, straying into errors and being forced to go in many directions, he completely destroyed all the paths leading to such errors, and brought it about that it stood on the firm foundation of a single faith. Moreover, finding the laws obscure because they had become far more numerous than they should be, and in obvious confusion because they disagreed with each other, he preserved them by cleansing them of the mass of their verbal trickery, and by controlling their discrepancies with the greatest firmness; as for those who plotted against him, he of his own volition dismissed the charges against them, causing those who were in want to have a surfeit of wealth, and crushing the spiteful fortune that oppressed them, he wedded the whole State to a life of prosperity. Furthermore, he strengthened the Roman domain, which everywhere lay exposed to the barbarians, by a multitude of soldiers, and by constructing strongholds he built a wall along all its remote frontiers. |

In reviewing the mosaic program of San Vitale, note how all of these priorities are manifested in the mosaics. As we will see these political and religious concerns play a central role in the mosaics of San Vitale, which are virtually a manifesto of Justinian's political and religious authority and orthodox Christianity. Von Simson, in his Sacred Fortress, has written: "San Vitale was to become the stage and setting proper to the sacred drama by which the emperor meant to communicate his theological and political concepts to the West (p. 23)."

Ravenna, located on Italy's Adriatic coast some eighty

miles south of Venice, rose to prominence during the fifth and sixth centuries.

In 404, the Emperor Honorius, being threatened by Visigothic invasion led by

their King Alaric, needed a new and more defensible capital. Ravenna's location

on the coast allowed effective communication with the capital of the eastern

empire in Constantinople. The swamps surrounding Ravenna provided a natural

defense for the new capital. In 476 Ravenna fell to Odoacer, the first Germanic

king of Italy, who in turn was overthrown by Theodoric, the king of the Ostrogoths

from 471, and ruler of Italy from 493-526. Theodoric made  Ravenna his capital

in 493. As king of Italy, Theodoric in the monuments he constructed in Ravenna

clearly emulated the tradition of Roman imperial monuments. This is well exemplified by the mausoleum in Ravenna that Theodoric constructed for himself about 520. In plan and materials it echoes the tombs made by Roman senatorial families. In 540, the Byzantine

general Belisarius conquered Ravenna, a critical step in Justinian's campaign

to restore Roman authority.

Ravenna his capital

in 493. As king of Italy, Theodoric in the monuments he constructed in Ravenna

clearly emulated the tradition of Roman imperial monuments. This is well exemplified by the mausoleum in Ravenna that Theodoric constructed for himself about 520. In plan and materials it echoes the tombs made by Roman senatorial families. In 540, the Byzantine

general Belisarius conquered Ravenna, a critical step in Justinian's campaign

to restore Roman authority.

St. Vitalis, a second century martyr, was believed to be the head of a family of martyrs who were associated with the local foundation of Christianity. St. Vitalis was believed to be the husband of St. Valeria and the father of Sts. Gervase and Prothase. According to the story of Gervase and Prothase, they along with St. Vitalis were martyred on the spot of a "little Colosseum," the site of the church of San Vitale. As effectively the "proto" or first martyr of Ravenna, St. Vitalis was seen as the spiritual head of the Christian community in Ravenna.

The Church was begun by the Orthodox bishop of Ravenna, Ecclesius (522-32), shortly after the death of Theodoric in 526. The church was apparently financed by Julius Argentarius, whose name suggests he was a banker. Several capitals bear the monogram of Bishop Victor (538-545). The Church was dedicated by Bishop Maximian (546-56) in 547. The apse mosaic shows on the left hand side St. Vitalis receiving the crown of martyrdom from the enthroned Christ, while on the right hand side of the same mosaic Ecclesius is shown presenting a model of the church. Bishop Maximian appears as the only labeled figure in the Justinian mosaic.

Since Maximian was appointed as bishop of Ravenna in 546, this suggests that the mosaic must be from after that date.

Architecture

Beautiful images of the interior spaces of San Vitale are found at the following web site: http://web.kyoto-inet.or.jp./org/orion/eng/hst/byzantz/sanvital.html. These images capture the effect of the interior of the church. In looking at these views, imagine yourself in the interior. What would be your response to the architecture? Remember that the church interior is a stage space for the celebration of the liturgy.

In its octagonal form, the church was understood as a martyrium to San Vitale. Von Simson writes: "Liturgically and mystically, a martyr's sanctuary is both his tomb and Christ's sepulcher; and early Christian theology conceived the dignity of martyrdom as the martyr's mystical transfiguration into Christ. The architecture of San Vitale, evoking this relation of the death and resurrection of the titular saint to the death and resurrection of Christ, is a significant tribute to the Christ-like dignity of St. Vitalis."

A useful collection of images of Ravenna mosaics can be found at a site entitled Images from World History. I would like to thank Erick Romero for this reference.

In order to "read" the mosaics and gain an understanding of the richness of their meaning, we must have an understanding of the nature of Biblical interpretation. From Early Christianity, Biblical interpretation played an integral role in religious experience. Biblical exgesis, or interpretation, traditionally defines four different levels of meaning: 1) literal or historical; 2) allegorical; 3) tropological or moral; 4) anagogical. Reading of the Bible is, thus, not limited to a record of past events, but is seen as a key to an understanding of a universal plan of history. Critical here is the relationship of the Old and New Testaments. The Old Testament is not seen as just an account of events before the time of Christ, but the events of the Old Testament are seen to "prefigure" or typologically connect to events of the New Testament. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), one of the Four Church Fathers, in his City of God (XVI. 26) states that "the New Testament is hidden in the Old; the Old is clarified by the New." Christ himself articulates this relationship when he compares Jonah's three days spent in the belly of the sea monster to the three days he would spend in the tomb awaiting Resurection (Matt. 12:40). The story of Jonah can also be seen to link to the sacrament of Baptism. In the ritual of Baptism, the immersion in water is seen as a dying of the old self and a rebirth through Christ. In a more general sense, the story of Jonah refers to the importance of faith and prayer as the way of salvation of the "elect" from damnation. Because of his belief in God, Jonah was willing to have himself cast into the sea in order to save his shipmates. This self-sacrifice by Jonah was regularly seen as an Old Testament prefiguration of Christ's Sacrifice on the Cross on behalf of humanity.

In your study of the mosaics, try to find the typological

parallels and relationships between the different parts of the mosaic program.

From the perspective of our knowledge of later Christian art, it is significant

to acknowledge the absence in the mosaics of San Vitale of direct representations

of New Testament images, but they are typologically alluded to in the other

mosaics. Pay special attention to the importance of the figures of Christ and

the Emperor Justinian. Note the number of different figures represented in the

mosaic program which can be typologically related to Christ or Justinian.

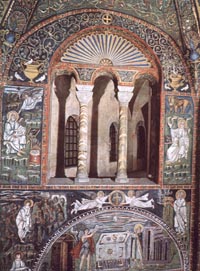

Chancel Vault

The entrance to the chancel is marked by a Triumphal Arch showing medallions with the Apostles and Gervase and Prothase. Christ appears at the apex or keystone of the arch. The chancel vault has at the center a representation of the Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God, directly above the altar. Christian iconography used the Agnus Dei as an allegorical representation of the "Sacrifice" of Christ. The symbolic link of the Agnus Dei to the altar beneath clearly establishes a vertical axis focusing on the sacrificial symbolism of the Eucharist. See how this symbolism is continued in the flanking north and south walls. The wreath encircling the Lamb can be related to the Triumphal crowns offered to Emperors or Generals to commemorate victories. The Child's Sarcophagus from the end of the fourth century has a comparable crown encircling the chi-rho and being supported by angels. Note that a similar crown is being presented to St. Vitale in the apse mosaic to commemorate his martyrdom. The wreath is supported on four sides by angels standing on orbs. The chancel vault is clearly connected to the tradition of dome architecture going back to monuments like Pantheon constructed by the Emperor Hadrian in the early second century:

As implicit in the dedication of the Pantheon to "All the Gods," the dome carried the traditional symbolism of univerality and all-inclusiveness. In the vault of San Vitale, the four angels standing on orbs clearly echoes this symbolism with the reference to the four corners of the world.

At the top of the wall marking the entrance to the apse appear three windows. Considering the central role the Trinity played in the doctrinal debates of the period, the windows clearly are a Trinitarian reference. As one of the primary sources of light in this interior, these windows carry the traditional light symbolism of the Trinity as equated to the light of the world. This use of triple openings is found regularly at San Vitale.

|

|

|

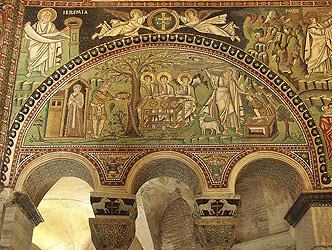

The north and south walls flanking the altar focus principally on Old Testament figures. The lunette on the north wall represents two different episodes in the story of Abraham and Isaac:

The center and left hand side of the mosaic represents the angels announcing to Abraham the birth of his son Isaac.

|

|

|

It is based on Genesis 18: 1-15: And the Lord appeared to him [Abraham] in the vale of Mambre as he was sitting at the door of his tent, in the very heat of the day. And when he had lifted up his eyes there appeared to him three men standing near him: and as soon as he saw them he ran to meet them from the door of his tent, and adored down to the ground. And he said: Lord, if I have found favour in thy sight, pass not away from thy servant. But I will fetch a little water, and wash ye your feet, and rest ye under the tree. And I will set a morsel of bread, and strengthen ye your heart, afterwards you shall pass on: for therefore are you come aside to your servant. And they said: Do as thou hast spoken. Abraham made haste into the tent to Sara, and said to her: Make haste, temper together three measures of flour, and make cakes upon the hearth. And he himself ram to the herd,, and took from thence a calf very tender and very good, and gave it to a yound man: who made haste and boiled it. He took also butter and milk, and the calf which he had boiled, and set before them: but he stood by them under the tree. And when they had eaten, they said to him: Where is Sara thy wife? He answered: Lo, she is in the tent. And he said to him: I will return and come to thee at this time, life accompanying, and Sara thy wife shall have a son. Which when Sara heard, she laughed behind the door of the tent. Now they were both old, and far advanced in years, and it had ceased to be with Sara after the manner of women. And she laughed secretly, saying: After I am grown old and my lord is an old man, shall I give myself to pleasure?And the Lord said to Abraham: Why did Sara laugh, saying: Shall I who am an old woman bear a child indeed? Is there any thing hard to God? according to appointment I will return to thee at this same time, life accompanying, and Sara shall have a son....

Notice how the mosaic includes a number of the details referred to in the text. Try to do a typological reading of the story. See how many of the details included in the text and mosaic have typological significance.

The right hand side of this mosaic represents the famous story of the Sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham. This is based on Genesis 22. Abraham is tested by the Lord and is called upon to sacrifice Isaac, his only son: And [Abraham] took the wood for the holocaust, and laid it upon Isaac his son: and he himself carried in his hand fire and a sword. And as they went on together, Isaac said to his father: My father. And he answered: What wilt thou, son? Behold, saith he, fire and wood: where is the victim for the holocaust? And Abraham said: God will provide himself a victim for an holocaust, my son. So they went together. And they came to the place which God had shewn him, where he built an altar, and laid the wood in order upon it: and when he had bound Isaac his son, he laid him on the altar upon the pile of wood. And he put forth his hand and took the sword, to sacrifice his son. And behold an angel of the Lord from heaven called to him, saying: Abraham, Abraham. And he answered: Here I am. And he said to him: Lay not thy hand upon the boy, neither do thou any thing to him: now I know that thou fearest God, and hast not spared thy only begotten son for my sake. Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw behind his back a ram amongst the briers sticking fast by the horns, which he took and offered for a holocaust instead of his son.

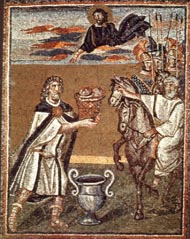

The Eucharistic symbolism of the lunette on the south wall is explicit with an altar bearing bread and wine between the figures of Abel and Melchisedech presenting their offerings. This mosaic conflates two narratives of offering from the book of Genesis. Abel is shown offering the "firstlings of his flock" that is part of the story of the offering of Cain and Abel.

Genesis 4:3-5: And it came to pass after many days, that Cain offered, of the fruits of the earth, gifts to the Lord. Abel also offered of the firstlings of his flock, and of their fat: and the Lord had respect to Abel and to his offerings. But to Cain and his offerings he had no respect: and Cain was exceedingly angry and his countenance fell.

Cain's jealousy will lead him to kill Abel. Melchisedech's offering is part of the story of Abraham when Melchisedech, the priest / king of Salem, offers Abraham bread and wine:

Genesis 14:18-20: But Melchisedech the king of Salem, bringing forth bread and wine, for he was the priest of the most high God, Blessed him, and said: Blessed be Abram by the most high God, who created heaven and earth. And blessed be the most high God, by whose protection the enemies are in they hands. And he gave him the tithes of all.

Note: Salem later became Jerusalem.

Hebrews 7: 1-2 : For this Melchisedech was king of Salem, priest of the most high God, who met Abraham returning from the slaughter of the kings, and blessed him. To whom also Abraham divided the tithes of all: who first indeed by interpretation, is king of Justice: and then also king of Salem, that is, king of peace....

Melchisedech's offering appears frequently in Early Christian art as exemplied by this nave mosaic from Santa Maria Maggiore:

Try to explain the inclusion of Abel and Melchisedech in the mosaics of San Vitale.

Eastern Spandrels on the North and South Walls

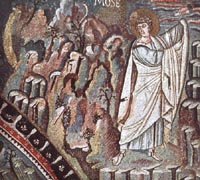

The eastern spandrel on the south wall shows the mission of Moses who appears first at the bottom tending the sheep of Jethro and again above with the calling of Moses by God in the Burning Bush to lead the Israelites out of Egypt.

Exodus 3:1-5: Now Moses fed the sheep of Jethro his father in law, the priest of Median: and he drove the flock to the inner most parts of the desert, and came to the mountains of God, Horeb. And the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush: and he saw that the bush was on fire and was not burnt. And Moses said: I will go and see this great sight, why the bush is not burnt. And when the Lord saw that he went forward to see, he called to him out of the midst of the bush, and said: Moses, Moses. And he answered: Here I am. And he said: Come not nigh hither, put off the shoes from thy feet: for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.

The eastern spandrel on the north side represents Moses receiving the Ten Commandments:

Try to explain the inclusion of these mosaics.

The western spandrels on the north and south represent Prophets: Jeremiah and Isaiah respectively. Isaiah prophecies were principally connected with the Incarnation of Christ, while Jeremiah was traditionally seen as the prophet of Christ's Passion.

The four evangelist appear on the next level. Each evangelist is associated with one of the corners of the chancel mosaic, and the division between the level shows the break between the Old and New Testaments:

|

|

|

The most famous mosaics in San Vitale are the pair of mosaics representing the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora. These appear in the apse adjacent to the apse mosaic representing Christ in Majesty. Justinian is shown carrying a paten, or bowl containing the Eucharistic bread, while Theodora carries the chalice or vessel for the Eucharistic wine. Maximian carries a cross, while a tonsured priest carries the Gospel book. These figures are preceded by another priest swinging an incense burner. The direction of these mosaics from west to east or towards the apse suggests both the bringing in the Eucharistic elements into the church and their presence as gifts to be offered to Christ above. The appears of the Three Magi or Kings bearing gifts on the hem of Theodora's robes reinforces the latter meaning. The moment represented has been identified liturgically as the Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Symbolically this entrance is understood to mark the First Coming of Christ (the Incarnation).

Christ in the apse is represented seated on a globe from which flow the four rivers of paradise. Christ holds in his hands a sealed book which is probably the Book of Life, which Christ will have at the time of the Second Coming and Last Judgment.

Analyze the organization and meaning of these mosaics, especially the Justinian one. Try to articulate the relationship of these to the other mosaics in the church. Consider what we have said to date in this course about the function of the imperial portrait. Otto von Simson includes in his Sacred Fortress the following discussion of the function of the imperial portrait:

"This image assumed its most important political function when an emperor had just ascended the throne or when he wished to demonstrate his authority even in the remotest parts of the Empire. Whether to legalize the imperial power or to proclaim it, the emperor's portrait was sent out in the most solemn way. When the procession carrying it approached a city, the whole population went out with candles and incense to pay homage to the new ruler. These 'sacred images,' as they were significantly called, were subsequently erected in a public place, an act which furnished the occasion for the declaration of submission on the part of the people (p. 28)."

Bishop Theodosius, at the Second Council of Nicea (787),

writes of the power of imperial images:

If the Imperial effigies are sent through the cities and the provinces, the

crowd comes to meet them bearing wax tapers and incense, thus honoring not a

picture painted in wax but the Emperor; how much more then should this happen

to the image of Christ our God painted in the Church, of his unstained Mother

and of all the Saints, both Blessed Fathers and Ascetics.

What do you make of the fact that Justinian never visited Ravenna?

Articulate the relationship of these mosaics to the rest of the mosaic programme.

Key Dates

404 Emperor Honorius makes Ravenna his western capital.

410 Sack of Rome by the Visigoths

455 Rome sacked by Vandals

476 Deposition of last Roman Emperor in the West, Romulus Augustulus. German King Odoacer captures Ravenna.

493 Control of Italy gained by Ostrogothic King Theodoric (he takes Ravenna from Odoacer)

522-532 Ecclesius Orthodox Bishop of Ravenna

524 Composition of Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius while waiting execution

526 Theodoric dies.

c. 526 San Vitale probably begun to be built by Ecclesius after the death of Theodoric

527 Justinian (born c. 482) begins his reign as Emperor in the Eastern part of the Empire

529- 534 Promulgation of by Justinian of first edition of the Corpus juris civilis

532 Nika revolt in Constantinople

532-537 Construction of Hagia Sophia (previous church destroyed in Nika revolt) in Constantinople

533 Byzantine conquest of north Africa by general Belisarius

535 Byzantine invasion of Italy

538- 545 Victor is the Bishop of Ravenna (several capitals in San Vitale bear his monogram).

540 Byzantine occupation of Ravenna; Persian invasion of Syria and capture of Antioch

546 Maximian appointed Bishop of Ravenna

547 Dedication of San Vitale

548 Death of the Empress Theodora

565 Death of Justinian

568 Beginning of the Lombard invasion of Italy

Related Web pages

The Buildings of Procopius (excerpts from Procopius, On Building)

Irina Andreescu-Treadgold and Warren Treadgold,"Procopius and the Imperial Panels of San Vitale," The Art Bulletin , 1997 (79). pp. 708-723 (available on JSTOR).

San Vitale of Ravenna. Pages prepared by Mary Ann Sullivan of Bluffton University.