| Wealth is indeed useful,

since it is both an embellishment for those who possess it, and the means

by which they may exercise virtue. It is also of benefit to one's sons,

who can by means of it rise more easily to positions of honor and distinction

[Leonardo Bruni, Preface to Book I of the Aristotelian Treatise on Economics,

or Family Estate Management Addressed to Cosimo de' Medici: p. 305]....

|

Richard Goldthwaite,

Wealth and the Demand for Art in Italy 1300-1600:

p. 206: ...Petrarch and the first generation of his followers

at the end of the fourteenth century who upheld the model of the contemplative

life, had embraced the ideal of poverty, inspired no doubt by Franciscan spirituality

but also by the Stoic doctrine of indifference to material things found in some

Roman writers.... The next generation of humanists, however, had very different

ideas, especially those Florentines who addressed themselves not so much to

other intellectuals as to a public of wealthy entrepreneurs. They discovered

a different side of Aristotle --above all, in the pseudo-Aristotelian Economics,

translated and edited by Leonardo Bruni --that opposed poverty and reevaluated

the importance of private wealth for both the well-being of society and the

self-fulfillment of the individual. Bruni, Alberti, and Matteo Palmieri, far

from condemning wealth, or being suspicious of it, now extolled it as a necessary

condition for the exercise of virtue in the active life. Wealth presents a moral

challenge because it puts virtue to the test in ways not experienced by the

person who is not burdened by the encumbrances of material possessions. These

Florentine writers assumed an active involvement in civic life, where the rich

have a special role to play; and they recognized both the reputation and the

special authority the rich enjoy among their fellows. What these intellectuals

were in fact doing was establishing the nobility of a wealthy upper class that

had no cultural traditions to appeal to for underpinning its status: its only

credential was wealth and what wealth could buy --political power and social

status....

The central problem that had to be addressed was the proper use

of wealth. The humanists considered the problem entirely in secular terms, although

their reliance on classical sources, above all Aristotle, who had exercised

so much influence throughout the Middle Ages, gave their arguments a familiar

ring. For them wealth does indeed have a usefulness beyond the traditional claims

on it by charity and good works, and this usefulness can be entirely a matter

of private advantage / p. 207: and pleasure.... To an extent they defined the

usefulness of wealth in the traditional aristocratic terms of glory seeking,

albeit now in a civic context; but the consumption model the humanists came

up with was not the traditional one of the feudal nobility. It reflected the

new habits of spending that possessed Italians at the time: it centered on architecture.

As indicated in the previous section, the quality of magnificence associated

with architecture was highly touted throughour the fifteenth century by numerous

writers.

| Magnificence is a more elevated form of liberality having to do with enormous

expenditures --for example, when someone builds a public theater, or sponsors

the Megalensian Games, or a gladiatorial show, or a public banquet. These

acts, and acts of this sort which surpass the powers of the average private

person, have a certain aura of greatness about them and are spoken of, not

simply as liberal, but as magnificent [Leonardo Bruni, An Isagogue of

Moral Philosophy, p. 276].... |

Magnificence is the key term in the discussion by the humanists

of the positive uses of wealth. In dealing with the subject they of course referred

to classical authorities; but at the same time they were also appropriating

a medieval notion associated with the uses of wealth by princes. Feudal princes

became more self-conscious about magnificence when they began to lead a more

settled existence. The concept involved the splendor with which they sought

to endow their presence with the authority of their position in the feudal hierarchy,

but it also called for generosity in the spirit of virtuous liberality. Medieval

discussions of liberality, largely inspired by Aristotle, focused on the right

uses of wealth: liberality was the mean between the extremes of the vices of

prodigality and avarice. It was, however, a princely virtue involving those

gestures of spectacle, feasts, gifts, and charity by which a prince asserted

a public presence.... Magnificence, in a sense,was a rationalization for luxury,

which was otherwise condemned as sinful and unnatural. In the courtly literature

of England, which has been carefully combed for usage of the term, magnificence

was synonymous with magnanimity and was inextricably associated with the Christian

concept of nobility; and it was demonstrated in generous and splendid hospitality

on a grand public scale. This sense of term continues to find expression in

the literary tradition through the Renaissance and into the seventeenth century....

The

January page from the Très riches heures presents a good

example of what Goldthwaite calls princely magnificence. In this miniature

the patron of the manuscript, Jean duc de Berry is shown celebrating

the New Years Day feast of étrennes. He and the rest of

his court is turned out in luxurious fabrics. On the side board are

exhibited the luxurious metalwork which were presumably gifts exchanged

at this feast. In the background hangs a tapestry illustrating the Fall

of Troy which provided the medieval noble the model of a good warrior.

The feast of étrennes was specifically associated with

the renewal of allegiances. The gifts exchanged gave physical testament

to the personal allegiances.

|

/p. 208: In Italy the term

underwent a redefinition to fit a nonfeudal society. The basic meaning remained

the same: magnificence is the use of wealth in a way that manifests those qualities

that express one's innate dignity, thereby establishing one's reputation by

arousing the esteem and admiration of others. But it is now distinct from princely

magnanimity and largely deprived of its overtone of Christian charity. It becomes

associated with that greatness of spirit so characteristic of the humanists'

notion of the civic nature of man. True to the Aristotelian idea, however, it

is regarded as a social concept, involving a grand gesture made toward the collectivity

of society if for no other reason than it provided a spectacle on the public

stage.

Also truer to the original

discussion of the concept in Aristotle, the Italians explicitly associate magnificence

with the proper use of wealth and money in general and not just by princes in

particular; it is a virtue that only the rich can possess.... Giovanni Pontano,

who takes up the subject in a tract written on just those social virtues that

involve the spending of money, opens his discussion calling magnificence the

"fruit" of wealth. Although magnificence involves an extraordinary

manifestation of wealth and luxury, these writers shift the emphasis from expenditures

for the public good to private expenditures to establish one's public reputation

or simply to give one pleasure. Aristotle had emphasized the public-spirited

nature of magnificence and only in passing allowed for its application alsos

to the furnishing of the rich man's house as a suitable use of his wealth. Alberti,

however, elaborates on how such possessions, by enhancing a man's reputation

and fame, strengthen the public image of his family and help build those networks

of friends that were so important in urban public life. Pontano, too, shows

how magnificence can consist of private posssessions as well as extravagant

expenditures for ceremonies, feasts, hospitality, gifts, and the other gregarious

activities of an expansive social life. Thus a classical notion with all its

added feudal overtones was detached from claims of feudal legitimacy and power

and appropriated to serve an elite in a society with different foundation....

pp. 220-221:

The concept of magnificence was by far the most frequently cited rationale for

building in fifteenth-cetury Italy. The point of departure was Aristotle's notion,

found also in Aquinas, that the virtuous use of money consisted in expenditures

for religious, public, and private things if they were permanent.... The humanists

took full possession of this classical notion that buildings as permanent private

monuments adorning public space assured the fame that great and worthy men seek.

"Since all agree that we should endeavor to leave a reputation behind us,

not only for our wisdom but our power too," asserts Alberti (appealing

to the authority of Thucydides), "for this reason we erect great structures,

that our posterity may suppose us to have been great persons." Building

is therefore an activity that could be rationalized (always echoing classical

authors) as the proper expression of one's inner qualities, a moral act as the

measure of a man: "the magnificence of a building," according to Alberti,

"should be adapted to the dignity of the owner," and for Palmieri

"he who would want...to build a house resembling the magnificent ones of

noble citizens would deserve blame if first he has not reached or excelled their

/p. 221 virtue."

p. 248: The

Medici palace represented one of the most splendid residences in fifteenth-centuy

Ialy, and the famous inventory of its contents made on the death of Lorzenzo

il Magnifico in 1492 reflects something of the new spending habits. The forms

of conspicuous wealth associated with princely treasuries in the north are less

in evidence: there is little silver plate, and liturgical utensils and vestments

in the chapel fill up less than three folio sides. Arms and armor are concentrated

in the chamber of Lorenzo's son Piero, and in the munitions rooms; and little

was in evidence in the rest of the house. Most of the gold jewelry falls into

the range of only 15 to 30 florins, and the most precious jewels are assessed

at no more than the ancient cameos. The extraodinary collection of Chinese porcelain

had a relatively modest monetary value. The most valuable items are antiquities,

such as cameos and objects made out of semiprecious stones. The splendor that

emanated from the contents of Italy's most magnificent household at the time

was not in the intrinsic value of rare materials or even in market value.

In the overall

picture of luxury expenditures, in short, consumption demonstrated taste more

conspicously than wealth. The more intimate relation with objects sharpened

one's appreciation of them for their craftsmanship apart from the inherent value

of materials and generated that self-conscious refinement of a sense of taste

that is one of the highest expressions of culture developed in Italy during

this period. Perhaps, as is often said, there is no accounting for taste; but

it is another /p. 249: matter when taste, whatever that taste may be, is extended

to new kinds of objects. What is taste, after all, but one way of transforming

physical objects into high culture, thereby rationalizing the feeling of possessiveness,

the sense of attachment to physical objects. These objects incorporated values

other than sheer wealth: for a product as mundane as a maiolica plate, these

values ranged from standards of personal comportment at table to the literary

erudition displayed by its painted decoration. These were social values through

which people sought to say something about themselves and to communicate that

to others, thereby establishing their credentials as a new elite, one of wealth,

to be sure, but also one of taste and refinement. As Sabba da Castiglione wrote

in his chapter on household ornaments, musical instruments, sculpture, antiquities,

medals, engravings, pictures, wall hangings all testify to the intelligence,

civility, and manners of the owner.

Splendor is

one word Italians repeatedly used in talking about this phenomenon. The humanis

Matteo Palmieri exalts splendor as the quality sought in all those things needed

to enhance one's life with beauty ("per bellezza di vita"), including

the house, its furnishings, and other apurtenances for living in private splendor....

Machiavelli observes that Italians eat and even sleep with greater splendor

than other Europeans; and Pontano criticizes the French because they eat only

to satisfy their gluttony and not to endow their lives with splendor. It is

the complement of magnificence, being the logical extension of magnificence

into the private world. Whereas magnificence is manifest in public architecture,

splendor expresses itself in the elegance and refinement with which one lives

his life within buildings; it therefore consists of household furnishings, everyday

utensils, and ornaments of personal adornment a things that do with town houses

as well as in the gardens that go along with villas in the countryside.

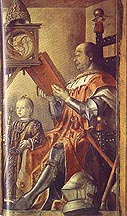

Portait of Frederigo

da Montefeltro and his son Guidobaldo: wearing the armor in which he made

his military reputation and reading a large manuscript, Federigo is shown as

both magnificent and wise, the exemplar of arms and of letters. Each element

of the picture adds to this argument. The duke's ermine-edged cloak and the

sceptre of his papal vicariate refer to the legality with which he held power.

He wears the heavy gold and enamelled chain of the chivalric Order of the Ermine;

around his calf he find the Order of the Garter, given to Federigo by King Edward

IV of England in 1474. The young Guidobaldo acts as a page-boy, carrying the

sceptre which he would inherit in due course. Appearing as a virtuous signore,

one acknowledged by the kings of Europe, there is no hint of the fact that Federigo's

accession in 1443 after his half-brother was assassinated was far from straightforward.

Cosimo de' Medici (1389-1464), Pater

Patriae, obverse, c. 1465/1469

bronze, diameter: .078 m (3 1/16 in.)

Inscription: COSMVS MEDICES DECRETO PVBLICO P[ater] P[atriae]

(Cosimo de Medici, the Father of the Country by Public Decree)

|

Florence Holding an Orb and Triple

Olive-branch, reverse, c. 1465/1469

bronze, diameter: .078 m (3 1/16 in.)

Inscription: PAX LIBERTAS QVE PVBLICA; across bottom: FLORENTIA

(Public Peace and Liberty/ Florence)

|

The Renaissance Medal

Excerpt from Laurie Schneider Adams, Italian Renaissance

Art, p. 145: A feature of the Classical revival in fifteenth-century

Italy was the production of medals, usually made of bronze or lead.

They were inspired by imperial Roman coins, which were smaller than

the medals but similar in design --a bust-length profile of an emperor

on the obverse, a emblem on the reverse, and an inscription.

|

|

|

|

Augustus,

Denarius, 19 B.C.

|

During the Renaissance, medals were commissioned by various

rulers and wealthy families as a way of circulating their images in

portable, relatively inexpensive form. In addition, the message conveyed

by the emblem or scene on the reverse could serve the function of political

propaganda. To a certain extent, the iconography of a medal and its

inscription provide biographical insights into the patron. Sometimes

medals were struck to commemorate the design of a building in which

case they can be useful architectural documents.

|

Excerpt from Vincent Cronin, The Florentine Renaissance, chapter entitled

"The Republic and the Medici":

/p. 59: The political development of Florence in the fifteenth century is intimately

linked with three generations of a single family.

The first Medici of consequence probably practised medicine, for the name is

a shortening of dei Medici -'of the doctors'- and the family blazon,

five red roundels or palle, probably represent pills or cupping glasses....

The Medici are heard of as a middle-class family during the fourteenth century

with political leanings toward the popolo minimo, lesser guilds, but

they remained unimportant until Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici founded a bank

specializing in accounts with the Roman Curia....

Giovanni married Piccarda, daughter of one Odoardo Bueri.... In 1389 Piccarda

gave birth to her first son, Cosimo. He received the usual primary education,

then /p. 60: took a step that influenced him for life: from the ages of fourteen

to seventeen he studied the classics in the house of Roberto de' Rossi, a rich

bachelor who had learned Greek from Emmanuel Chrysoloras.... Cosimo became an

enthusiast for the new learning and planned a journey with Niccolò Niccolo

to look for Greek manuscripts in the Holy Land, but his father, whose shelves

held only three books --the Gospels, the Legend of St. Margaret, and a sermon

in Italian-- doubtless did not sympathize with this new kind of pilgrimage.

Anyway, Cosimo started at once in the family bank....

In 1414 Cosimo made an excellent marriage to Contessina Bardi, whose family

were Giovanni's partners, and undertook his first important job....

/p. 61:In 1424 Cosimo became branch agent of the Medici bank in Rome, a responsible

post because Rome was the most profitable branch in relation to invested capital,

the yield exceeding 30 per cent....

On his father's death in 1429 Cosimo became head of the bank and Florence's

second richest citizen. The classics --particularly a treatise on economics

attributed to Aristotle-- had given him a different attitude toward wealth from

old Giovanni's. Cosimo believed that in so far as virtue was action, money could

foster virtue. As his friend Poggio expressed it in a dialogue Concerning

Avarice, private and public life would be ruined if each man earned only

what is strictly necessary. "Money is an indispensable goad for the State,

and those who seek money must be considered its basis and foundation."

This more positive outlook towards money combined with Cicero's more positive

outlook towards citizenship. Cosimo had already stood for, and held, office;

now, as the head of the family, he decided to follow an active political career.

Here it becomes necessary to look at Florence's constitution.

Citizenship was confined to members of the guilds, that is, to men following

a recognized profession or trade. Out of an estimated male population over twenty-five

of 14,500, perhaps 6,000 were citizens: that is, they had the right to vote

and hold office. But the important thing is that the ranks were open. Anyone

[male that is], whatever his birth, might become a citizen by matriculating

into one of the guilds. When it came to filling Councils or magistracies, members

of the Greater Guilds --wool and cloth merchants and professional men-- were

given a marked numerical advantage --roughly in the ratio of three to one--

over members of the Lesser Guilds --carpenters, blacksmiths, harness-makers

and so on. Florence, then, was a republic with, for that time, a widely based

franchise, but its constitution favoured the merchant class.

/p. 62:

Excerpt describing Cosimo de' Medici from Gene Brucker, Renaissance Florence:

p. 119: Cosimo de' Medici ...[was] the most prominent citizen that reached manhood

in the early fifteenth century. Vespasiano da Bisticci's biography of Cosimo

is laudatory and uncritical, but it is an honest evaluation of the man, /p.

120: and depicts him as he was seen by the majority of his fellow-citizens.

No modern biographer has succeeded in penetrating the surface of Cosimo's personality,

of exposing the man behind the public facade. We can use this facade, however,

to measure some of the changes that had occurred in the life style of the patriciate.

Cosimo's authority derived from his great wealth and his leadership of a faction.

Vespasiano da Bisticci described a conversation between Cosimo and a political

rival, in which the former articulated his political philosophy: "Now it

seems to me only just and honest that I should prefer the good name and honor

of my house to you: that I should work for my own interest rather than for yours.

So you and I will act like two big dogs who, when they meet, smell one another

and then, because they both have teeth, go their ways. Wherefore now you can

attend /p. 121: to your affairs and I to mine." He demonstrated a particular

talent for working behind the scenes, achieving his goals by manipulating others.

His instruments were the bonds of obligation by which he tied his supporters

to himself. Vespasiano wrote: "He rewarded those who brought him back [from

exile], lending to one a good sum of money, and making a gift to another to

help marry his daughter or buy lands...." His political enemies were not

killed but exiled; the refusal to shed blood was characteristic of this cautious

politician who gained his objectives by less flamboyant methods. In one sense,

his style represented the triumph of the mercantile mentality. He typified the

rational and calculating entrepreneur, the shrewd, toughminded realist who had

banished passion and emotion from politics.

The material dimensions of Cosimo's life also reflect significant

innovations in the patrician mode of living. The construction of a massive palace

on the Via Larga provided the arena for a more refined and luxurious style of

existence, which set the pattern for the Florentine upper class. Although Cosimo

deliberately affected the manner of an old-fashioned merchant with simple tastes,

his living style signalled the abandonment of such traditional virtues as austerity,

thrift, and frugality, and the acceptance of ostentation as a socially desirable

trait. The new ethic received political sanction with the repeal or the nonenforcement

of sumptuary legislation, a characteristic feature of communal policy in earlier

times. Seven years after Cosimo's death, his grandson Lorenzo stated that the

Medici had spent over 600,000 florins for public purposes since 1434, and he

remarked that this expenditure "casts a brilliant light upon our condition

in the city." The living standard in the Medici palace was more luxurious

than Cosimo's ancestors had ever known. This expenditure for magnificent decor,

costly furnishings, and elegant clothing was designed to provide an impressive

setting for prominent guests, to create an image of Medici (and Florentine)

wealth and taste. Cosimo was host to both the German emperor Frederick III and

the Byzantine emperor John Paleologue, as well as other, less distinguished

princes of church and state who dined and lodged in the palace on the Via Larga,

or in the villas at Careggi and Cafaffiuolo. The Medici were not the only /p.

122: Florentine family to dispense lavish hospitality, but the scale and opulence

of their entertainments marked them as the city's most illustrious house. A

visit to the Medici household was a dazzling experience, as young Galeazzo Maria

Sforza, son of the lord of Milan, testified in letters to his father Francesco.

This product of a courtly milieu extolled the beauties and charms of the villa

at Careggi, and praised the musical and dramatic entertainments which were provided

for his amusement.