Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments |ARTH 213 Assignments

Donatello's David

|

Medici Palace Court |

Probably the most famous example of fifteenth-century sculpture is the bronze David by Donatello. Dates for the work vary from the 1430s to the 1460s. It is recorded as the centerpiece of the first courtyard in the Palazzo Medici during the wedding festivities of Lorenzo de' Medici and Clarice Orsini in 1469. Some have argued that it was commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici in the 1430s to be the centerpiece of the courtyard of the older Medici house on the Via Larga.

The following collection of images demonstrates the wide popularity of the image of David and Goliath in fifteenth century Florentine art. It is well known that David was a symbol of the Florentine Republic, which like the Old Testament youth stood up to its rivals.

|

Master of the David and Saint John Statuettes, David, c. 1490. |

||

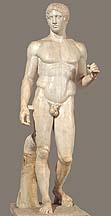

The

nakedness of Donatello's bronze David stands out starkly in contrast

to the other fifteenth century images of David. Even though other works show

knowledge of the Donatello bronze, like the hand holding the sword in Bellano's David or

the hand on the hip in the Master of the David and Saint John Statuettes, David, none

of them repeat the nudity of the Donatello. The choice of bronze, the nudity,

and the contrapposto pose all put this work in the Humanist context of emulating

the antique. While referencing the classical contrapposto pose in the tradition

of Polyclitus's Doryphoros, Donatello has softened the static balance

and firm stance of the traditional male figure. This softening is evident in

the placement of the two hands as well as the way David's free leg gently rests

on the head of Goliath. The

smooth, polished skin is set off against the rougher boots and curly locks

of hair. This reference to touch is especially apparent in the detail of the

feather stroking the inner thigh of David's leg and in the detail of the way

David runs his toes through the locks of Goliath's beard. There is a disjunction

between David's refined and graceful pose with the apparent reverie and beauty

of the facial expression and the gruesomeness of the decapitated head of Goliath

at his feet. It is hard to imagine this beautiful youth has moments ago had

been engaged in mortal combat and cut off the head of Goliath.

The

nakedness of Donatello's bronze David stands out starkly in contrast

to the other fifteenth century images of David. Even though other works show

knowledge of the Donatello bronze, like the hand holding the sword in Bellano's David or

the hand on the hip in the Master of the David and Saint John Statuettes, David, none

of them repeat the nudity of the Donatello. The choice of bronze, the nudity,

and the contrapposto pose all put this work in the Humanist context of emulating

the antique. While referencing the classical contrapposto pose in the tradition

of Polyclitus's Doryphoros, Donatello has softened the static balance

and firm stance of the traditional male figure. This softening is evident in

the placement of the two hands as well as the way David's free leg gently rests

on the head of Goliath. The

smooth, polished skin is set off against the rougher boots and curly locks

of hair. This reference to touch is especially apparent in the detail of the

feather stroking the inner thigh of David's leg and in the detail of the way

David runs his toes through the locks of Goliath's beard. There is a disjunction

between David's refined and graceful pose with the apparent reverie and beauty

of the facial expression and the gruesomeness of the decapitated head of Goliath

at his feet. It is hard to imagine this beautiful youth has moments ago had

been engaged in mortal combat and cut off the head of Goliath.

|

|

|||

A useful interpretive strategy has been to place the statue in the context of fifteenth century notions of male identity. Whereas girls became brides in their teens, men did not marry generally until their mid-twenties or later. Adolescence was thus an extended period between childhood and full adult maturity for the male in Renaissance Florence. Portraits of youthful males like the Botticelli above have a strong effeminate quality. The figure's slim proportions, long locks of hair, and detached glance parallel those of the Donatello David. The social construction of the adolescent in Renaissance Florence is given visual form in these representations.

Excerpt from Adrian W.B. Randolph, Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence,

p. 184: Given its breadth, the ramifications of male sodomitical practices touched all Florentines in one way or another. So famous was the city on the Arno for promoting it, that in Germany, homosexual sex was described by the verb florenzen, and in France its was called "the Florentine vice."...

/p. 185: In a phrase destined to become one of the more renowned in Renaissance studies, Rocke describes the omnipresence of sodomy in fifteenth-century Florentine culture: "In the later fifteenth century, the majority of local males at least once during their lifetimes were officially incriminated for engaging in homosexual relations." In this simple and carefully worded statement lies the basis for a radical reappraisal of sexuality in early Renaissance Florence. Sodomy, rather than representing a dusty and esoteric corner of historical analysis, moves to center stage. No longer can modern binaries emphasizing heterosexual relations be taken as an unquestioned given. We must realign our sights on the past, taking into account the cultural norm produced by homosexual relations in early modernity. Another of Rocke's conclusions follows from this . Male-male sexual relations were not eccentric, but they were in fact important constituent elements in the production of Renaissance masculinity and therefore contributed fundamentally to the shape of public life in a broad sense. For the condemnation of homosexual relations did more than yield interest for dowries and build communal brothels, it also structured social relations, and most importantly, relations between men.

It would, as Rocke indicated, be misleading to speak of a "homosexual subculture" in fifteenth-century Florence. Homosexual relations, although proscribed and circumscribed, were nonetheless a pervasive and "centric" mode of behavior, linking individuals normally separated by class and by neighborhood affiliations....

/p.186: The picture painted by Rocke of male-male sex is panoramic. It occcurred throughout the city, involving men from all walks of life. Its publicness, even though it is recorded fundamentally through its prosecution, emerges clearly. In fifteenth-century Florence, although defined as "unmentionable" by social critics and theologians, sodomy possessed as irrepressible life of its own. Not only was it practiced widely and publicly by Florentines, but it produced particular categories of masculinity, structuring "homosocial" relations. The language of prosecution --derived directly from theology-- provides the basis for describing particular male roles within homosexual relations. In an overwhelming majority of cases, such relations involved an older, active partner and an adolescent, passive partner. Adult males only rarely pursued other adult males; indeed, Rocke asserts that ninety percent of the "passive" partners recorded in court proceedings were eighteen years old or younger, concluding that the "focus of men's homoerotic was on what Florentines called 'fanciulli,' or boys, and we would tend to call adolescents." Most passive adolescents were not prosecuted for their 'crimes.' Active male sodomy was, on the other hand, perceived as punishable: the penetrator was the perpetrator. Having said that, active sodomy did not represent a threat to a man's masculine identity. His virility, if anything, represented a reinscription of male sexual power. The passive partner was quite differently defined. He was seen as "effeminized" and altered by the act. But even this redefinition did not substantially threaten masculinity, for the passive role was seen as a temporary phase, one the adolescent would quickly shed with maturity. The cultural gaze produced by the adult and active masculine desire for the passive adolescent male body constituted one important aspect of Florentine homosociality.

On the streets of Florence, the male adolescent body was both a compromised site for homoerotic gazing and also an expressive sign, guaranteed effective via its potential innocence and purity. In early Renaissance Florence a "boy" was himself a sexual drama. To understand how the David embodied this dialectic between desire and its repression, one must take the culture of fifteenth-century Florentine sodomy into account....

/ p. 188: The David is not entirely naked. His large hat, perhaps originally adorned with a feather, draws as muc attention to his nudity, as his naked body emphasizes the striking presence of this contemporary headdress. The inclusion of a hat was an iconographic novelty. Although David was sometimes represented with a garland, the distinctive hat in Donatello's bronze David remarkable. That it is a modern hat would have brought to the fore the performative aspect of the statue, which is today somewhat obscured by historical distance. The hat reminds us that the David represents a quotidian drama, which contemporaries would have recognized. It is curious, and to /p. 189: my mind very suggestive, that within popular culture sodomitical culture, the hat, too, signifies prominently.

Rocke describes in detail the 'game' of hat stealing, which he calls "a sort of ritual extortion for sex." Men seeking sodomitical sex would swipe the hats of the boys who attracted them and refuse to hand the caps back unless the adolescents succumbed to their advances. "I won't ever give it back to you unless you service me," cried Piero d'Antonio Rucellai, according to his victim, the fifteen-year-old Carlo di Guglielmo Cortigiani, testifying in a trial of 1469. After submitting to sex in an alley, Cortigiani got back his hat. On the street a hat on an attractive boy would have drawn attention. It was a signal of potential gratification. The retention of a hat, conversely, transmitted the conservation and reassertion of corporeal and sexual authority.

The hat atop the head of the bronze David can be seen to reproduce this ambivalence. It amplified the "boy's" seductive beauty by coding the adolescent body as desirable. On the other hand, David's garlanded hat, so firmly on his head and beyond the reach of the beholders below, simultaneously functioned to underscore the boy's victory. If one sees the David as embodying the victory of an adolescent boy over the homoerotic gaze, his otherwise iconographically inexplicable hat takes on new significance, symbolizing the boy's retention of honor and dismissal of sexual "attack." While still, perhaps, attracting stolen homoerotic gazes, David's atemporal and predestined victory over any such spectatorial thievery is cast in bronze. The hat, therefore, might elicit a desirous visuality, but, from the front, David's serious innocence conjoined with his brazen nudity simultaneously would have undermined all lasciviousness. Like the boy-saint Pelagius, who, when fondled by the Caliph of Cordoba, threw off his clothes taunting his persecutor with that which was unattainable, the David seems both to elicit and to dismiss attraction percisely through its nudity.

Paradoxically enticing and dismissive, the boy warrior rose above

all heads in the courtyard of the Medici palace. The unplacated adult male

gazes rising up to meet the David were aligned, therefore, with the

remnant  of male power at the boy's feet: Goliath's head. There is an automatic

analogy between Goliath and the viewer. At the feet of the boy, the beholder

calibrates his gaze with that of the felled Philistine; like Goliath, the

viewer is to be punished, struck by the power of the reflected and blunted

gaze.

of male power at the boy's feet: Goliath's head. There is an automatic

analogy between Goliath and the viewer. At the feet of the boy, the beholder

calibrates his gaze with that of the felled Philistine; like Goliath, the

viewer is to be punished, struck by the power of the reflected and blunted

gaze.

In both its representation and reception the statue ignites the homerotic gaze only to extinguish it. The statue does not leave the homoerotic gaze unpunished. Goliath is beheaded, and the active and desiring eyes of the viewer are --morally-- shut with the Philistine's. It is precisely this moral trumping that makes the homoeroticism of the David both licit and effective.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of Francesco Sassetti and His Son (?), c. 1485

Excerpt from Christopher Fulton, "The Boy Stripped Bare by His Elders: Art and Adolescence in Renaissance Florence," Art Journal, 56, 1997, pp. 31-40:

p. 31: In the milieu of fifteenth-century Florence depictions of adolescent males were self-consciously employed in the training and socialization of youth. What makes the heuristic art of this period especially intriguing, and even paradoxical, is its frequent homoreroticization of the young male subject. Here an effort is made to explain the reasons why this homoerotic element appeared in Florentine portrayals of adolescent males and how it may have worked on a quattrocento audience. By paying heed to the social foundation for these images, one discovers that the artistic treatment of youth, instead of proclaiming a liberation from social strictures, served as an instrument in the enforcement and reproduction of patriarchal authority.

"Boys will be men" --or so one might subtitle Ghirlandaio's double portrait of a dignified man of affairs and his dreamy-eyed child. Ostensibly an image of the Florentine merchant Francesco Sassetti with his second son, Teodoro, whose names appear in an inscription at the top of the image, the painting shows the father sitting with magesterial aplomb as the paterfamilias: strong, majestic, impassive, and possessed of the virtues of gravitas and manly nobility that are endlessly extolled in the humanistic literature of the period. The boy, in pointed contrast, is a rather insubstantial creature and portrayed as a dependent: physically slight, even frail, his clothing and adornments deriving from his father's largesse. At an immature stage of development, he leans for support against the grown man's side, his gaze expressing awe and reverence for his elder while also appealing for paternal recognition. But, conspicuously, the boy's affections are not returned. The male parent remains the silent bulwark of the family and a distant idol for the youth's admiration; psychologically remote, the father is cut off from his son's entreaties. How is one to understand these disturbing inequalities portrayed in Ghirlandaio's painting? What is the nature of the emotional passivity of the elder , the anxious fixation of his son?

One may begin by considering the social status of adult men in quattrocento Florence. To prepare themselves to assume the responsibilities of heading a family unit, males from this social environment customarily postponed their marriage and sired children only after they had achieved a measure of status in the community. The resultant gaps in age contributed to psychological rifts between husbands and their wives and between fathers and their children. In the special case of the father-son relationship, the division caused by the discrepancy in age was exacerbated by prevalent mores and patterns of social interaction. Boys were easily intimidated by fathers who adhered to the moral principles of gravity and self-control. The /p. 32 ethic of the Florentine merchant inhibited the display of affection and undermined strivings for emotional contact. Additionally, fathers of the mercantile elite took the business of rearing their male progeny with deadly seriousness. They aspired to raise dutiful and responsible heirs who would perpetuate the estate and augment the family's honor, and, to these ends, a male child's upbringing and education tended to be extremely strict and highly regulated. Florentine youth were not allowed to develop according to their innate tendencies or desires; rather, their conduct and actions were closely supervised by the controlling hand of fathers and their appointed surrogates.

With no role in business or politics, excluded from adult organizations, and though sexually potent or at least incipiently so and as yet unmarried, male adolescents composed a marginalized population within quattrocento Florence, estranged in the indeterminate social space between the spheres of maternal care and adult male enterprise. For once a boy began to show the capacity to distinguish between virtue and vice, at around the age of seven, he left the care of his mother, "il sceno domestico," in the words of Matteo Palmieri, for moral training and education under his father's supervision. Throughout the difficult period of adolescence, while boys were required to leave behind feminine attitudes associated with the domestic realm, they were yet withheld the privileges and dignity reserved for grown men. In an effort to lay claim on the benefits of adulthood, youths often clashed with their fathers over resources and symbols of authority, thus tingeing the father-son relationship with an element of competition that occasionally erupted in envy, suspicion, and even hostility....

In an effort to abate the threats represented by obstreperous youth, the adult community instituted social mechanisms for taming the independent wills of their sons. Adolescent confraternities and informal secular brigades channeled the energies of young men into the city's ritual life; ecclesiastical schools and private humanist tutors inculcated Christian values and a deep respect for elders.

[relate the deployment of age in Ghirlandaio's Confirmation of the Franciscan Order, from the Sassetti Chapel to the discussion above]