Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments

Excerpts from:

Mary D. Garrard

Leonardo da Vinci: Female Portraits, Female Nature

from Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, New York, 1992, pp. 58-86:

p. 59: In this essay, I will suggest a way of looking at Leonardo's art that reveals it as indeed abnormal, but in social rather than psychological terms. For Leonardo presented through art a view of the female sex that was culturally abnormal in the patriarchy of his day: woman understood individually as an intelligent being, biologically as an equal half of the human species, and philosophically as the ascendant principle in the cosmos. His position deserves our attention, for it was distinctive in a period when women were neither politically nor socially empowered to make such a case for themselves.

I begin with the earliest preserved portrait by Leonardo's hand, the Ginevra de'Benci in the National Gallery, Washington, D.C., probably painted in the late 1470s, which puts forth a fundamentally /p. 60: new female image. The sitter is posed in a three-quarter view and engages the eyes of the viewer. Full-faced female sitters appeared occasionally in Northern European portraits of the fifteenth-century, and in painting Ginevra de' Benci, Leonardo may have followed a Netherlandish type, just as he shows some influence of Netherlandish style. In Italy, however, Leonardo's portrait of Ginevra de'Benci was revolutionary, setting in motion the replacement of the profile portrait type customary for women in the first three-quarters of the fifteenth century....

The change in the preferred pose for female sitters initiated by Leonardo was of greater than mere formal significance. Occasionally in Northern fifteenth-century portraits, but --as far as I can tell-- never before in Italian portraits, does a female sitter look directly into the eyes of the viewer. The difference is profound, for the reason that Leonardo himself stated in the famous aphorism "The eye is said to be the window of the soul." The sitter who looks at the viewer confronts us personally, piercing the picture plane to establish a psychic intercourse in human time....

Recent feminist scholarship has clarified the terms of this exceptionality. As Patricia Simons has shown, the Quattrocento profile portrait convention presented young women, usually at the time of their marriage, as beautiful but passive possessions of male heads of households, inert mannequins for the display of family wealth to the gaze of other males. The convention supported patriarchal values, draining the bride of any sign of inner animation or worth, and reifying the inequality of the marital partners. By contrast, Leonardo presents the woman named Ginevra de' Benci in dramatically different terms: imbued with psychic life, she confronts the viewer's gaze with an icy, noncoquettish stare. The latter distinction is important, because it separates the National Gallery painting from a class of female "portraits" that emerged at the turn of the sixteenth century, of which Bartolomeo Veneto's Portrait of a Woman is an example, women recognizable as courtesans or prostitutes by their provocative gaze at the viewer, a posture that marked them as brazen because, in art, ordinary /p. 61: Renaissance wives did not directly engage the (male) viewer's eye.

But then,

Ginevra de' Benci was not an ordinary Renaissance wife. She was a member of

a wealthy and educated family, the Benci, who were of considerably greater

cultural influence than the man she married in 1474, Luigi Niccolini. Ginevra's

grandfather, Giovanni de' Benci, was general manager of the Medici bank and

an artistic patron in his own right; her father, Amerigo, was patron and friend

of the Neoplatonist Marsilio Ficino. Ginevra de' Benci herself, born in 1457,

was recognized as a poet, though we know almost nothing of her literary work.

The Washington picture was long ago identified with a portrait of Ginevra

de' Benci said by Vasari and other writers to have been painted by Leonardo

da Vinci, and it has long been regarded as her marriage picture. The identifying feature of the image is the juniper bush behind the sitter's

head, which recurs as a sprig on the obverse of the panel, an allusion to

the name "Ginevra" (the Italian for juniper is ginepro).

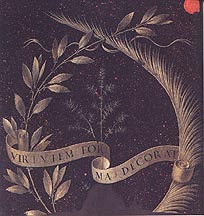

The inscription on the obverse, VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT (she adorns her virtue

with beauty), has been taken to refer to the attributes relevant to the sitter's

status as a bride.

The identifying feature of the image is the juniper bush behind the sitter's

head, which recurs as a sprig on the obverse of the panel, an allusion to

the name "Ginevra" (the Italian for juniper is ginepro).

The inscription on the obverse, VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT (she adorns her virtue

with beauty), has been taken to refer to the attributes relevant to the sitter's

status as a bride.

As a woman of renowned beauty, Ginevra de' Benci was also the subject of ten poems written by members of the Medici circle, Cristoforo Landino and Alessandro Braccesi, and of two sonnets by Lorenzo de' Medici himself. The ten poems were commissioned by Bernardo Bembo (the father of the writer Pietro Bembo), who was in Florence in 1475-76 and again from 1478 to 1460 as Venetian ambassador, and who --by evidence of the poems-- selected Ginevra de' Benci as the object of his platonic love. It has recently been argued that Bembo may have also commissioned the portrait now in the National Gallery. Jennifer Fletcher has pointed out that the emblematic design on the verso of the panel, a bay laurel and a palm branch encircling a sprig of juniper, is almost identical with Bernardo's personal device, a near-circular wreath formed by embracing laurel and palm branches, with varying elements inside. In this interpretation, the emblem painted by Leonardo on the back of the panel should be read as Bernardo's impresa framing Ginevra's, paralleling her desire to join herself to his family line, a desire attributed to Ginevra herself by Landino (and Fletcher).

Bernardo's passion for Ginevra may have been personally grounded, but it also partook of a poetic literary convention in which a female paragon of ideal beauty, beloved by the poet, inspires his love, virtue, and artistic achievement. The classic models are Dante's Beatrice and Petrarch's Laura. Leonardo's portrait of Ginevra de' Benci, along with its emblematic verso, has been linked with this genre by Elizabeth Cropper, as a painter's response to Petrarch's claim that perfect beauty could not be realized in a pictorial image. Cropper argues that in Leonardo's Ginevra, "the poet's denial of the validity of painted appearance is refuted through painting itself," and that the image joins the discourse of competition between /p. 62: painting and poetry, demonstrating the power of art to sustain the presence of the absent living. Thus she interprets the juniper behind the sitter's head on the verso as a punning reference to her own name, Ginevra, which is intended to invoke the parallel association of Petrarch's Laura with laurel.

These new interpretations of the Ginevra de' Benci portrait --that it was produced to signify Bembo's platonic (or romantic) love for Ginevra, and that it was produced to demonstrate the power of the art of painting -- offer fresh explanations for the painting's genesis. The Bembo thesis in particular is useful for moving the work out of the category of the conventional marriage portrait and for permitting a stylistically more plausible dating, between 1476 and 1481....

/p. 64: The unconventionality of the Ginevra de' Benci is sustained in other female images produced by Leonardo. Two portraits painted at the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan, where Leonardo worked from 1483 to 1499, both partake of and deviate from the category they helped establish. Most firmly accepted as autograph is the portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, paramour of Duke Ludovico and, like Ginevra de' Benci, a woman of a noble family who wrote poetry. Acclaimed for her incomparable beauty and sparkling intelligence, Gallerani was noted for her ability to carry on learned discussions with famous theologians and philosophers. She wrote epistles in Latin and poems in Italian, which were celebrated in other poems. Orphaned at about fifteen on her father's death in December 1480, she was taken up by Duke Ludovico, who gave her a residence at Saronno in 1481, and for ten years she was his lover. Tradition has described Cecilia Gallerani as the duke's mistress, but it is difficult to reconcile her high social status and intellectual renown with the previously clandestine and inferior position of mistresses at court. More likely, Gallerani's position at the Sforza court was as an early instance of the courtesan, the new type emerging in the late fifteenth century who --in contrast to the silent, chaste, and obedient wife-- was rhetorically celebrated as intelligent, accomplished, outspoken, and sensual. She may herself have been a model for the court lady who would be celebrated a quarter century later by Castiglione[Book III of the Courtier]....

Leonardo's portrait of Cecilia Gallerani painted ca. 1484-85, is widely recognized as a major advance in the history of portraiture, introducing, as Martin Kemp describes it, a new "living sense of the sitter's deportment" and "of human communication," as Gallerani is seen to interact with someone outside the picture, an achievement for which "there simply is not equal...in contemporary or earlier portraiture...." This self-possessed woman now rotates on her own axis and firmly grasps the animal that alludes either to her own name... or to the ermine that was the duke's emblem. The prominent hand exhibits the force of ideal structure, rhyming in shape with the animal under its control, and thereby suggesting that the sharp, fierce creature might stand for an aspect of her personality or for someone under her dominance....

| The portrait of the living ermine, whose fur was much sought after, served a threefold purpose: its designation in Greek, galee, was a pun on the sitter's family name; it was a well-known symbol of purity because it was believed too fastidious to soil itself; and it was a heraldic emblem of the duke of Milan [Ludovico Sforza]- from Joanna Woods-Marsden, "Portrait of the Lady, 1430-1520," in Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo's Ginevra de' Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, David Alan Brown ed., 2001, p. 76. |

There is, in fact, a strking analogy between the situations of artists and mistresses, whose relationships with their ducal patrons were undergoing similar transformation in the late Quattrocento courses: from mistress to courtesan, from craftsman to artistic genius. Each was a move from a hierarchic business relationship to a more personal one that acknowledged the intellectual brilliance of the artist or courtesan, resulting in a gain in status (though perhaps a loss of personal freedom). Leonardo was at that moment personally helping to accomplish the transition for the artist and, in this context, he would have had reason to identify with a brilliant woman whose social progression mirrored his own....

/p. 67: The spectacular example of resistance to commodification is the so-called Mona Lisa, the world's most famous portrait, of a woman who --whatever else she may be-- is no known person's mistress and only conjecturally someone's wife. A host of writers on the Mona Lisa, from Walter Pater to Kenneth Clark, have recognized that it is not only, and perhaps not at all, a portrait, but rather an image that conflates portraiture with broader philosophical ideas. The picture have begun as a Florentine female portrait ca. 1503-6, but it is not known to have left Leonardo's hands, and when he went to France for the final three years of his life, he almost certainly took the painting with him....

Since the nineteenth century, the Mona Lisa has frequently been identified as a female archetype. This is typified by Walter Pater's famous description (1869): "She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave." Pater's version of the archetypal female draws heavily upon the nineteenth-century femme fatale, yet he implies an identity between this ancient woman, or Woman, and the cycles of geological time. Simlarly Kenneth Clark noted that the woman's face and the landscape background together express the processes of nature as symbolized by the image of a female, whose connection with human generation links her sex with the creative and destructive powers of nature. The medical historians Kenneth D. Keele at once localized and enlarged this interpretation, identifying in the portrait image unmistakable signs of a woman at an advanced stage of pregnancy, /p. 68: which he understood as a symbol of Genesis, "God-the-Mother...enclosed within the body of the earth."

More recently, David Rosand has connected the Mona Lisa with the Renaissance concept of the portrait as an image of triumph over mortality and death. Pointing to Leonardo's preoccupation with transience and the ravages of time (O Time, who consumes all things!), Rosand quotes the artist's competitive edge held by art over destructive nature: "O marvelous science [i.e. painting], which can preserve alive the transient beauty of mortals and endow it with a permanence greater than the works of nature; for these are subject to continual changes of time, which leads them to inevitable old age." According to Rosand, the Mona Lisa holds in dialectical tension the fluid and changing landscape, subject to endless deformation by water, agent of time and the generative and destructive forces of life, with the contrasting image of perfect human beauty --a figure who, in life, would undergo the same transformations of time but who, as a creation of art, will live forever. In Rosand's view, the beautiful woman is not herself identified with the forces of nature, except as a product of them, subject to their ravages; symbolically, she is allied with the realm of art, as image of perfection and permanent substitute for transitory life. In this interpretation, the Mona Lisa is another example of the genre of female portraits in which a beautiful woman's image represents the triumph of art, functioning, in Elizabeth Cropper's words, "as a synedoche for the beauty of painting itself."

The Mona Lisa conspicuously departs from this convention, however, in the very hypnotic strangeness that has made it uniquely famous, in Leonardo's personal stylization of a beauty that is quite different from living or ideal specimens. Moreover, as many writers have observed, she is of a piece with her setting. Laurie Schneider and Jack Flam have pointed to "a system of similes" between figure and landscape, of visual echoes between curved arcs and undulating folds, and to a unity between them expressed through the diffuse lighting and consistent sfumato. Martin Kemp has also taken account of the extraordinary geological activity in the background of the Mona Lisa, which he sees (as did Keele and Clark) as coextensive with the portrait image, not in dialectical opposition to it. Noting correspondences between the flowing movements and dynamic processes visible in the landscape and the cascading, rippling patterns of the lady's clothing and hair, Kemp describes them as united exempla of the "processes of living nature." For Kemp, the painting expresses Leonardo's idea of the earth as a "living, changing organism," a macrocosm whose mechanisms and circulations of fluids are echoed in the microcosm of human anatomy, and whose fecundity is echoed in "the procreative powers of all living things."

Webster Smith has likewise interpreted the Mona Lisa as a micro-macrocosmic commentary on the geological processes of the earth, pointing to Leonardo's comparison of the circulation of blood in the human body with rivers on the earth.

| [Man has been called by the ancients a lesser world and indeed the term is well applied. Seeing that if a man is composed of earth, water, fire, and air, this body of earth is similar. While man has within himself bones as a stay and framework for the flesh, the world has stones which are the supports of earth. While man has within him a pool of blood wherein the lungs as he breathes expand and contract, so the body of the earth has its ocean, which also rises and falls every six hours with the breathing of the world; as from the said pool of blood proceed the veins which spread their branches through the human body so the ocean fills the body of the earth with an infinite number of veins of water.... The cause which moves the water through its springs against the natural course of its gravity is like that which moves the humours in all the shapes of animated bodies [Quotation from Leonardo's Notebooks]] |

...Smith reminds us that for Leonardo this relationship is not merely metaphoric, since he describes earth not as "like a living body" but literally as a living body. Smith is hard pressed, however, to explain why this philosophical commentary should be joined with a female portrait ....

Missing from these analyses is a framework that would situate in historical perspective the analogy between woman and nature, an analogy that was already ancient in the Renaissance. The use of a female figure to symbolize the nutritive and generative processes of nature is found in a long line of writers, from Plato, who described the earth metaphorically as "our nurse," to the twelfth-century poet Alain of Lille, who ascribed human and natural generation to a cosmic force personified as the goddess Natura. The figure of Natura creatrix had been given impetus by Roman writers such as Lucretius and Cicero, who believed the universe to be ruled by an intelligent and divine female Nature, identical with god yet immanent in the material world. As a deity this figure was exalted in the early Middle Ages by Boethius and Claudian. Claudian describes how "mother Nature made order out of elemental chaos," preserving one of many versions of the creation myth in which the creator of the universe is female....

|

[ In Antiquity and the Middle Ages it had been a regular practice to personify Nature by a usually reclining female figure, like Terra or Tellus. For example, at the bottom of the breastplate of the Augustus of Primaporta shows this figure: Another comparable figure is found at the bottom of the late fourth century silver plate made for the Emperor Theodosius, the Missorium of Theodosius: Note how in these examples the figure of Terra or Natura is regularly subordinated (subjugated) to the male power above and in the heavens.] |

However, in ancient and medieval philosophy the metaphoric figure of a powerful and creative female Natura coexisted with misogynous beliefs about the deficiency of woman's nature. The key text for the negative gendering of nature is Aristotle's Generation of Animals, where it is argued that human procreation is the result of the generative action of masculine form upon inert female matter.

| [the female does not contribute semen to generation, but does contribute something, and that this is the matter of the catamenia, or that which is analogous to it in bloodless animals, is clear from what has been said, and also from a general and abstract survey of the question. For there must needs be that which generates and that from which it generates; even if these be one, still they must be distinct in form and their essence must be different; and in those animals that have these powers separate in two sexes the body and nature of the active and the passive sex must also differ. If, then, the male stands for the effective and active, and the female, considered as female, for the passive, it follows that what the female would contribute to the semen of the male would not be semen but material for the semen to work upon. This is just what we find to be the case, for the catamenia have in their nature an affinity to the primitive matter [Aristotle, Generation of Animals, 729 a, as translated by Arthur Platt in The Basic Works of Aristotle, Richard McKeon ed.]] [ See also webpage entitled Form and Matter.] |

This viewpoint provided the philosophical foundation for the Christian view of nature as corrupt and the female as corrupting, epitomized by Saint Augustine's doctrine of original sin, and for the nexus that developed in the Middle Ages between the evil of the flesh, the negativity of matter, and the femaleness of matter....

Leonardo entered a discourse to which he made a conscious and original contribution, by affirming to a remarkable extent that the relationship between nature and the female passed beyond the metaphoric, and by presenting evidence in his anatomic studies that directly refuted dominant views about women's deficiencies. Although he had once depicted sexual intercourse in an image that distinctly privileged the male role, reflecting Aristotle's influential dictum that females contributed only passive matter to human procreation while the male played the vitalizing part, he increasingly questioned this theory. Instead, Leonardo drew upon the philosophical opinion of Lucretius and the medical opinion of Galen that both female and male contribute "seed" necessary for conception....

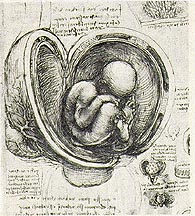

The so-called Great Lady drawing, which dates from ca. 1510, exemplifies his adoption of a new understanding of human generation. In an annotation on this sheet..., Leonardo challenges the Aristotelian view of generation... that the "spermatic vessels" (ovaries) do not generate real semen, observing instead that these vessels "derive in the same way in the female as in the male." Here he adopts the Galenic position that both sexes contribute in equal part. Elsewhere, citing the ability of a white mother mating with a black father to produce a child of mixed color, Leonardo concludes that "the semen of the mother has power in the embryo equal to the semen of the father." On /p. 70: the same sheet, he asserts that the mother nourishes the fetus with her life, food, and soul (anima), countering the Aristotelian belief still commonly held then that women, deficient in soul, were made incubators for gestation: "As one mind governs two bodies...likewise the nourishment of the food serves the child, and it is nourished from the same cause as the other members of the mother and the spirits, which are taken from the air --the common soul of the human race and other living things." Leonardo further appears to identify the active power of the womb as generative rather than nutritive, an important distinction within the camp of those who considered the womb to have an active power, under which nutritive virtue would generate something joined to it, while the greater virtue, generative, would produce a distinct entity....

In the "Great Lady" drawing, Leonardo presents a synthesized image of circulatory, respiratory, and generative processes in the female body. The drawing differs significantly in this respect from his representations of male anatomy, which typically illustrate blood circulation, the genito-urinary system, and other workings in independent images. The distinctive graphic completeness of the drawing expresses Leonardo's precocious awareness that blood flow in the female body is linked with its role in procreation, and implies his comprehension of the systemic order of organic process in the female body.... If we remember Leonardo's preoccupation with the interconnected functions of microcosm and macrocosm, it is a short step from here to a belief that the living earth is female, in its regenerative capability and its mysterious life-supporting powers.

For all that Leonardo wrote, it was to his visual explorations that he entrusted the primary task of representing nature: "Painting presents the works of nature to our understanding with more truth and accuracy than do words or letters." Because for Leonardo art was an instrument of discovery, a form of knowing and not merely an illustration of what was already known, the anatomical drawings reveal a process of visual reasoning....

/p.71: [Speaking the drawing of a fetus] Originating in observation but developed under belief in the correspondence between microcosm and macrocosm, the image gives information about human birth that is of a philosophical order, expressing its connection with other forms of birth and growth in the universe. Leonardo found analogy everywhere --the movement of wind currents is like that of water currents, and the trajectories of a bouncing ball are like both. "The earth has a spirit of growth," he said, whose flesh is the soil, whose bones are the mountains, whose blood is its waters.

Leonardo's belief in the interconnection of nature's largest patterns and smallest elements was sharply at odds, however, with prevailing beliefs about nature in the fifteenth century. A medieval distinction that remained in force throughout the Quattrocento was that between natura naturans and natura naturata, between the dynamic, generative principle and the inert material result of that creation. For Alberti, Nature was a vestigial female personification (carried over from the medieval allegorical figure of Natura), "the wonderful maker of things" who "clearly and openly reveals" such things as the correct proportions of the human body. The principles of Nature's true order --largely mathematical and proportional-- might be inferred from disparate imperfect examples by the artist, who could reproduce them in corrected form. In this way of thinking, art was not to imitate the mere phenomena of nature (natura naturata) but, rather, its higher invisible principles (natura naturans); and by giving them perfected visible form, art could successully compete with Nature herself.

The strength of this theory, and its intensification under the Neoplatonist doctrines that dominated later fifteenth-century Florence, may be the chief reason why Quattrocento art does not display a linear progressive naturalism. The hierarchic distinction between an abstract creative principle and the discredited material forms of the visible world effectively kept intellectually serious painters (such as Piero della Francesca) from too close an involvement with the latter. The hierarchy /p. 72: was reinforced by its gender associations, in that the Aristotelian differentiation of form and matter --the active male principle molding passive and static female matter-- supported the binary opposition of, and value distinction between, natura naturans and naturata. However, creative and material nature were in another sense conflated into a single entity, a female Nature whose creative powers were challenged by the male artist. These overlapping metaphoric structures are most clearly expressed in the model of perspective space construction, in which the artist positions himself outside nature, the better to attain mastery over it, and assigns his eye hierarchic priority over the segment of the world that it surveys, symbolically the whole of nature.

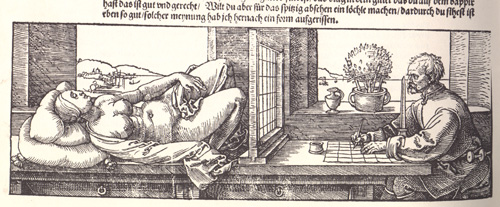

What is implied in the Albertian perspective diagram is boldly stated in an image by Dürer [see linked page for other recent critical discussions of this image], where we see the omniscient male eye focused through a framing device upon his subject, recumbent female form, who is surely a metonymic figure of Nature herself: objectified, passive matter, a mere model, waiting to be given meaningful form in art by the creative powers of the artist....

/p. 73: In

Leonardo's ... painting, the Virgin of the Rocks, the Louvre version

of the 1480s, material nature is described in meticulous detail, but in a

form that assures the presence of cosmic nature as well. The distinctive difference

lies not in the degree, but in the nature of Leonardo's naturalism.  Here,

as in numerous independent drawings, Leonardo forms the image of a plant in

shapes that emphasize its pattern of growth, implying that the source of change

is within matter and not transcendent of it. The arrangement of the leaves

at the plant's base evokes the spiral form of generation, now presented as

inseparable from matter itself....[Rather than seeing nature as a cosmic power]

Leonardo expresses its [Nature's] cosmic operations through its particulars,

deriving his understanding of the larger movements from observation of the

smaller....

Here,

as in numerous independent drawings, Leonardo forms the image of a plant in

shapes that emphasize its pattern of growth, implying that the source of change

is within matter and not transcendent of it. The arrangement of the leaves

at the plant's base evokes the spiral form of generation, now presented as

inseparable from matter itself....[Rather than seeing nature as a cosmic power]

Leonardo expresses its [Nature's] cosmic operations through its particulars,

deriving his understanding of the larger movements from observation of the

smaller....

/p. 77: Leonardo was in may ways a man of his age, for he not only shared but helped define his era's faith in the capacity of art to preserve life and transcend time. In his passionate championing of the art of painting, the artist had no peer, and he proclaimed often in his notebooks what many other Quattrocento artists believed, that " the painter strives and competes with nature." However, that was only part of Leonardo's complex understanding of the relationship between nature and art. In both his writings and his art, he demonstrated constantly that nature (mentioned far more frequently than God) is the superior guide, the teach of all good artists. Implicit in his thinking about art and nature is a recognition of nature's preeminence: "for painting is born of nature --or, to speak more correctly, we shall call it the grandchild of nature, for all visible things were brought forth by nature, and those her children have given birth to painting." In a similar spirit, he announces nature's superiority to technology: "Though human ingenuity may take various inventions which, by the help of various machines, answer the same end, it will never devise any invention more beautiful, nor more simple, nor more to the purpose than Nature does; because in her inventions nothing is wanting and nothing is superfluous...."

[H]is faith in human ability to control or direct nature was limited, both by his own pessimism and by his respect for nature's ultimate superiority. This point of view was not common in Renaissance Italy, when the quest to master and dominate nature grew /p. 78: steadily, and such slogans as "art is more powerful than nature" (Titian's motto) were brandished. Leonardo's drawings representing the Deluge may thus be understood as a response to man's dream of mastering nature. In those images of ferociously spiraling explosions of water, a giant apocalyptic flood repeatedly destroys the tiny structures of cities and towns. It is a celebration, rare in Italian Renaissance art, of the superior power of nature over human civilization --implicitly also a gender construct, of the endurance of female generation over male culture.

See page showing Images of Women in Fifteenth Century Art. This page also includes relevant excerpts from Leonardo's Notebooks.

Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments