Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 200 Assignments | ARTH 213 Assignments | ARTH 294 Assignments

Mona Lisa and Her Sisters

[large]

| Leonardo undertook to execute, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Monna Lisa, his wife; and after toiling over it for four years, he left it unfinished; and the work is now in the collection of King Francis of France, at Fontainebleau. In this head, whoever wished to see how closely art could imitate nature, was able to comprehend it with ease; for in it were counterfeited all the minutenesses that with subtlety are able to be painted, seeing that the eyes had that lustre and watery sheen which are always seen in life, and around them were all those rosy and pearly tints, as well as the lashes, which cannot be represented without the greatest subtlety. The eyebrows, through his having shown the manner in which the hairs spring from the flesh, here more close and here more scanty, and curve according to the pores of the skin, could not be more natural. The nose, with its beautiful nostrils, rosy and tender, appeared to be alive. The mouth, with its opening, and with its ends united by the red of the lips to the flesh tints of the face, seemed, in truth, to be not colors but flesh. In the pit of the throat, if one gazed upon it intently, could be seen the beating of the pulse. And, indeed, it may be said that it was painted in such a manner as to make every valiant craftsman, be he who he may, tremble and lose heart. He made use, also, of this device: Monna Lisa being very beautiful, he always employed, while he was painting her portrait, persons to play or sing, and jesters, who might make her remain merry, in order to take away that melancholy which painters are often wont to give to the portraits that they paint. And in this work of Leonardo's there was a smile so pleasing, that it was a thing more divine than human to behold; and it was held to be something marvellous, since the reality was not more alive. [Vasari, Lives of the Artists] |

This passage from Vasari's biography of Leonardo da Vinci in his Lives of the Artists is the foundation for the identification of the portrait in the Louvre as that of Lisa di Antonio Maria Gherardini, the wife of the prominent Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo. "Mona" is an abbreviation of the Italian ma donna, or my lady. In France, the painting is known as La Joconde after her husband's name. This identification appears to have been confirmed by the discovery in 2005 of a marginal note in a 1477 edition of the Epistolae ad familiares of Cicero.

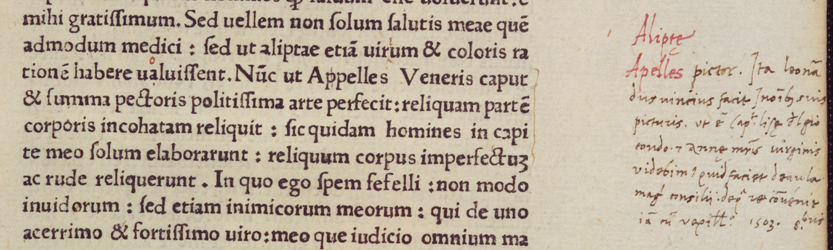

The marginal note written in October of 1503 by Agostino Vespucci compares Leonardo to the great classical painter Apelles and states that Leonardo is working on a portrait of "Lisa del Giocondo":

| Apelles the painter. That is the way Leonardo da Vinci does it with all of his paintings, like, for example, with the countenance of Lisa del Giocondo and that of the holy Anne, the mother of the Virgin. We will see how he is going to do it regarding the great council chamber, the thing which he has just come to terms about with the gonfaloniere. October 1503 [See Wikipedia] |

Vespucci's note is not only important for the identification of a portrait by Leonardo of Lisa del Giocondo but it also should be seen in the context of the Cicero passage which describes Apelles' working method:

| Nunc ut Appelles [sic] Veneris caput et summa pectoris politissima arte perfecit; reliquam partem corporis incohatam reliquit.... |

| As Apelles completed the head and upper part of the chest of Venus with the greatest art; the remaining part of the body was left incomplete.... |

While documenting that Leonardo was working on the portrait of Lisa del Giocondo in 1503, the marginal note's connection to the Cicero passage which comments on a half completed painting of Venus by Apelles suggests that Leonardo's painting was half completed. The Vasari passage describes how Leonardo after toiling on the Mona Lisa for four years had still not completed the painting. Leonardo took the painting to France, and when he died in 1519, it was inherited by his close assistant Salai. After the latter's death in 1524, the Mona Lisa along with Leda and the Swan, the Madonna, Child, St. Anne, and a Lamb, another portrait of a woman, the St. John the Baptist, the St. Jerome, and other works were included in an inventory of his possessions that were inherited by his sisters. By the 1540s, the Mona Lisa is recorded as being in the possession of Francis I at Fontainebleau.

There will always be intriguing alternative identifications, but the most convincing identification of the sitter of the Louvre portrait is Lisa del Giocondo. While accepting this identification, the question emerges as to the function of the painting. Significantly the painting never belonged to the Giocondo family. It is important to understand the Mona Lisa in the context of the functions or purposes of portraits of women in Leonardo's own art and Italian painting in general.

Fifteenth century Italy is understood as the first great period of European portraiture. While frequently associated with the Burckhardt idea of the "Discovery of the Individual", the creation of portraits needs to be understood in the context of their social and cultural functions. Many of the portraits women need to be understood in the context of the central role of the family in Italian social life. For the elite families marriage alliances and the need for off-spring to continue the dynastic claims are motivating factors in the creation of portraits of women.

A double portrait of a man and woman possibly by Fra Filippo Lippi and dated to the early 1440s contains elements that became conventional for portraits of women in the context of fifteenth century portraiture: the profile point of view, elaborate dress and coiffure, jewels, an interior setting with a window looking out at a landscape beyond. In a highly influential article published in 1988, Patricia Simons explored this tradition of profile portraits [see excerpts]. Lorenzo di Ranieri Scolari and Angiola di Bernardo Sapiti have been proposed as the subjects of this painting. The motto lealtà or "loyalty" embroidered into the woman's sleeve with gold thread and pearls suggests that this painting was intended to document the marriage.

One of the most magnificent female portraits of the fifteenth century by Domenico Ghirlandaio illustrates a slightly different function of the female portrait. The portrait represents Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni. Giovanna was the wife of Lorenzo Tornabuoni, the eldest son of Giovanni Tornabuoni. The couple had been married in 1486. The following year, she bore son, but died during her second childbirth in October of 1488. The dress she wears identifies her as a member of the Tornabuoni family. The interlaced "L" on shoulder refers to her husband Lorenzo and the diamond was an emblem of the Tornabuoni family. The objects in the niche behind her call attention to her piety and purity. The cartellino on the wall can be translated as: "O art, if you could depict character and soul, no painting on earth would be more beautiful." [compare to the following Leonardo passage: "A good painter has two chief objects to paint, man and the intention of his soul; the former is easy, the latter hard, because he has to represent it by the attitudes and movements of the limbs.... The most important consideration in painting is that the movements of each figure expresses its mental state, such as desire, scorn, anger, pity, and the like."]The date inscribed on the cartellino suggests that the portrait is probably posthumous. While documenting the alliance between two dominant Florentine families, the Ghirlandaio is probably intended to honor her fulfillment of her primary obligation to continue the family lineage and the ultimate sacrifice she made to fulfill this obligation.

Giovanni Tornabuoni, Giovanna's father in law, was apparently very interested in documenting the family through portraiture. Bronze portrait medals for both Giovanna and her sister in law Lodovica Tornabuoni have come down to us. Their portraits were also included in the fresco cycle decorating the Tornabuoni family chapel commissioned by Giovanni from Domenico Ghirlandaio. Conforming to conventions, Lodovica's status as a maiden is signified by her hair hanging down her back. It is important to note how both women are identified on the medals by their relationships to Tornabuoni men: in the case of Ludovica she identified as the daughter of Giovanni, while Giovanna is labeled as the wife of Lorenzo Tornabuoni. It has been suggested that a double portrait of a man and woman in the Huntington Library in San Marino is perhaps a portrait of Lodovica and her husband Alessandro Nasi who were betrothed in 1489 and married in 1491. Attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, the Huntington portrait share a number of elements in common with the Giovanna Tornabuoni portrait.

|

|

The Huntington double portraits continue conventions found in the Fra Filippo Lippi portrait. The woman, unlike the man, is set in an interior space with a loggia in the background overlooking a landscape beyond. The three-quarter point of view of the man is in contrast to the pure profile of the woman.

Patricia Simons emphasizes the role the profile portraits played in the political and social ambitions of Florentine families:

| The age of the women in these profile portraits, along with the lavish presence of jewelry and fine costumes (usually outlawed by sumptuary legislation and rules of morality and decorum), with multiple rings on her fingers when her hands are shown, and hair bound rather than free-flowing, are all visible signs of her newly married (or perhaps sometimes betrothed) state. The woman was a spectacle when she was an object of public display at the time of her marriage but otherwise she was rarely visible, whether on the streets or in monumental works of art. In panels displayed in areas of the palace open to common interchange, she was portrayed as a sign of the ritual's performance, the alliance's formation and its honorable nature. |

Or as Mary Garrard succinctly sumarizes Simons' discussion: "The Quattrocento profile portrait convention presented young women, usually at the time of their marriages , as beautiful but passive possessions of male heads of households, inert mannequins for the display of family wealth [and status] to the gaze of other males."

These two paintings by Botticelli, while they at first seem to conform to the profile portrait convention, diverge from this in notable ways. The profiles are not pure, but rather the heads are slightly turned so that you can see a little bit of the far eye. Also in contrast to portraits like Ghirlandaio's portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni, the perfect and highly stylized hair style of the Ghirlandaio has been loosened in these two Botticelli portraits. The Frankfurt panel breaks from the standard convention of the woman facing left. Scholars have generally agreed that while the same person, likely Simonetta Vespucci, is the model for both paintings, that these two are intended to present an ideal of female beauty. Scholars have related these to the tradition of love poetry from Petrarch and the ideas of ideal beauty. Petrarch wrote love poetry dedicated to "Laura." As in the tradition of the courtly love, Laura is unattainable; it is destined to be an unrequited love. This tradition was continued in the circle of the Medicis in the fifteenth century. In 1469 Lorenzo de' Medici organized a jousting tournament in honor of Lucrezia Donati, the wife of Niccolò Ardinghelli. As conventional in the context of courtly love, the relationship between Lucrezia and Lorenzo was platonic rather than physical. Lorenzo and his circle dedicated poems to extolling virtues of Lucrezia who was seen as the revered object but unattainable object of their affections. Verrochio was commissioned to do a portrait of Lucrezia apparently for Lorenzo.

Giuliano de' Medici, Lorenzo's brother, dedicated his attention to Simonetta Vespucci, who was born Simonetta Cattaneo and married Marco Vespucci in 1468. In 1475 Giuliano awarded Simonetta the victor's crown from a tournament he sponsored. The humanist poet Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494) devoted a poem commemorating this tournament entitled La giostra. The poem was a part of a cult dedicated to la bella Simonetta likely written after her untimely death the following year and Giuliano's own death the next year. Botticelli's panels along with his Venus and Mars in the National Gallery in London provide visual testament to this cult:

The physiogomy and details of the hair of the Venus figure have striking similarities to the woman in the Frankfurt portrait. The wasps that buzz around the head of Mars in the London panel suggests an association with the Vespucci family which had on its coat of arms wasps (Vespucci in Italian means "little wasps). It is has been noted that the pearl net woven into the hair of the woman in the Frankfurt panel was known as a vespaio because of its similarity to a wasp's nest.

While the Berlin and Frankfurt portraits and the London Venus and Mars are likely based on Simonetta Vespucci, these figures can also be likened to Petrarch's descriptions of his Laura especially with the elaborately curled hair:

| Breeze, blowing that blonde curling hair, stirring it, and being softly stirred in turn, scattering that sweet gold about, then gathering it, in a lovely knot of curls again, you linger around bright eyes whose loving sting pierces me so, till I feel it and weep, and I wander searching for my treasure, like a creature that often shies and kicks: now I seem to find her, now I realise she’s far away, now I’m comforted, now despair, now longing for her, now truly seeing her. Happy air, remain here with your living rays: and you, clear running stream, why can’t I exchange my path for yours? (227: La Canzoniere) |

The two Botticelli portraits of Simonetta and the Verrocchio portrait of Lucrezia that was likely commissioned by Lorenzo were intended to present visual equivalents of the poetic descriptions. Probably owned by men these paintings became substitutes for the unattainable objects of their romantic attentions. We can not assume that these portraits are accurate likenesses of their subjects. In fact they are more likely representations of an idealized beauty, the contemplation of which was understood in Neoplatonic thought to draw one closer to God. There can be seen a parallel between the lover trying to attain the unattainable lover, and the poet and artist with their literary and visual descriptions trying to represent these embodiments of unattainable divine beauty. As Poliziano writes: "He inwardly praises her arms, her face, and her hair, and in her he discerns something divine."

Botticelli alludes to this in the Frankfurt panel with the detail of the cameo necklace showing the competition between Apollo and Marsyas. Botticelli's detail is based on an antique gem owned by Lorenzo de' Medici and that was the source of several bronze copies. The story of the satyr Marsyas's attempt to defeat the divine Apollo in a musical competion was popular in the Renaissance as relating the artists' attempts to achieve divine beauty.

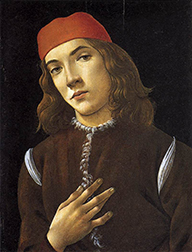

In these two portraits, therefore, it seems that Botticelli has taken the conventional formula of the profile portrait and has modified it to the context of romantic love. Consider what Botticelli has done to the male portrait in the portrait dated to 1482-83 in the National Gallery of Art in Washington:

|

The Portraits of Women by Leonardo

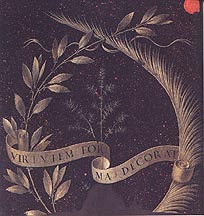

Leonardo's earliest portrait of a woman is the Ginevra da Benci in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The identification is based on a reference in Vasari to a portrait of Ginevra who had married Luigi Niccolini in 1474. The three-quarters point of view and the figure set into a landscape are in striking contrast to the conventional marriage portraits of the period.While still disputed, the function of the portrait is widely accepted as a commemoration of the platonic attachment of a Venetian diplomat and humanist Bernardo Bembo to Ginevra. Petrarchan poems written by members of the Medici circle commemorate this relationship. Ginevera's own father, Amerigo, was a patron and friend of the Marsilio Ficino, the most important Neoplatonist in the Medici circle. The laurel and palm branch enframing a juniper sprig on the back have been associated with the emblems of Bembo and Ginevra. The juniper reappears behind the head of Ginevra and is a pun on Ginevra's name (juniper in Italian is ginepro). The motto on the reverse, Virtutem forma decorat or "Beauty decorates virtue," suggests the context of Neoplatonic discussions of beauty. Like the Botticelli portraits related to Simonetta Vespucci discussed earlier, Leonardo likely intended this painting to be a visual statement of beauty in rivalry to the poetic descriptions [for more on this painting, see the excerpts from the Mary Garrard article].

The Lady with an Ermine in Kraków is generally accepted to be a portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, who was the mistress of Ludovico Sforza from 1489 to 1491/92. Leonardo would have painted this while he was serving as Ludovico's painter in Milan. The alert glance and active turning pose of Cecilia is in striking contrast to the traditional portraits of the period. Leonardo is drawing an analogy between Cecilia's alertness and that of the ermine she holds in her arms. Like the juniper trees in the Ginevra da Benci portrait, the ermine which in ancient Greek would have been translated as galée is undoubtedly a pun on Cecilia's family name, Gallerani. It also might be a reference to Ludovico who was invested into the Order of the Ermine by the King of Naples in 1488. Ludovico was sometimes called L'Ermillino. Leonardo's attention to texture accentuates the way Cecilia gently strokes and fondles the ermine. Cecilia herself was not a passive, silent figure. She was known among the humanists at the court of Milan for both her beauty and intelligence. She was known for her poetry and her oratory. The funds given her by Ludovico granted Cecilia an independence not known to many other women of the period. It is not certain whether Ludovico or Cecilia commissioned the painting. She perhaps would have wanted the painting as a reminder of her relationship to Ludovico.

A sonnet published in 1493 by Bernardo Bellincioni, a Florentine poet active in the Sforza court, records a dialog between Nature and the Poet celebrating the Cecilia Gallerani portrait and the superior power of painting: "How many paintings have preserved the image of divine beauty of which time or sudden death have destroyed Nature's original, so that the work of the painter has survived in nobler form than that of Nature, his mistress [see Garrard, p. 65]."

A drawing of Isabella d'Este should be considered here. Isabella was the daughter of Ercole I d'Este and Eleonora of Naples. Isabella married in 1490 Francesco II Gonzaga, the Marquess of Mantua. Her younger sister, Beatrice, married Ludovico in 1491. The marriages of Isabella and Beatrice had been arranged since they were six and five respectively. After Beatrice's death in childbirth in 1497, Isabella contacted her sister's rival Cecilia requesting to borrow the Leonardo portrait with the prospect of having Leonardo paint her portrait. The Louvre drawing is all that remains from this proposed commission, but she would become an important patron of the arts, including artists like Raphael and Titian among others. She had a good humanist education and a special passion for music. Isabella used her position as the Marchesa of Mantua to become one of the leading female figures in the cultural and political worlds of the Italian Renaissance.

[large] |

We can now return to the Mona Lisa. It is important see the painting in the context of conventional marriage portraits like the Ghirlandaio portrait of possibly Ludovica Tornabuoni. Both artists place the sitters in a loggia looking out on a landscape. The bases of columns are visible on the ledge behind the figure.  Later copies like one in the Walters Art Museum show the columns much more prominently. This suggests that the painting was cut down at some point, but

Later copies like one in the Walters Art Museum show the columns much more prominently. This suggests that the painting was cut down at some point, but  the recent discovery in the Prado of a version of the Mona Lisa that appears to have been done concurrently with the Louvre painting by a student suggests that the columns were cut off. The relationship of the figure to the landscape is radically different between the Mona Lisa and the Ghirlandaio. The woman in the latter painting is cut off from the background landscape especially with the prominent column. In the Leonardo it has long been noted how the figure is integrated into the mysterious landscape. The eye-level of the sitter is the same as the landscape's horizon. The columns enframe the landscape and do not bar the figure from it. Mary Garrard's article develops the relationship of the woman to the landscape. As has been noted above the profile view was the dominant convention of marriage portraits in Florence during the fifteenth century. It is likely that Leonardo is making reference to this by the positioning of the chair arm as parallel to the picture plane. If the figure was turned in the direction of the chair, she would be in a profile looking left as was the convention in profile marriage portraits. While referencing the conventional marriage portrait, Leonardo is also drawing a dramatic contrast.

the recent discovery in the Prado of a version of the Mona Lisa that appears to have been done concurrently with the Louvre painting by a student suggests that the columns were cut off. The relationship of the figure to the landscape is radically different between the Mona Lisa and the Ghirlandaio. The woman in the latter painting is cut off from the background landscape especially with the prominent column. In the Leonardo it has long been noted how the figure is integrated into the mysterious landscape. The eye-level of the sitter is the same as the landscape's horizon. The columns enframe the landscape and do not bar the figure from it. Mary Garrard's article develops the relationship of the woman to the landscape. As has been noted above the profile view was the dominant convention of marriage portraits in Florence during the fifteenth century. It is likely that Leonardo is making reference to this by the positioning of the chair arm as parallel to the picture plane. If the figure was turned in the direction of the chair, she would be in a profile looking left as was the convention in profile marriage portraits. While referencing the conventional marriage portrait, Leonardo is also drawing a dramatic contrast.

It is significant that the Agostino Vespucci marginal reference to Leonardo painting the Mona Lisa comments on a passage in which Cicero refers to Apelles painting a picture of Venus. This identifies Leonardo as Apelles and the Mona Lisa as Venus, the embodiment of divine beauty. Vasari's account of the painting alludes to this in his reference to the smile: "[I]n this work of Leonardo's there was a smile so pleasing, that it was a thing more divine than human to behold...."

Like the juniper branches in the Ginevra da Benci and the ermine in the Cecilia Gallerani, the smile of the Mona Lisa is undoubtedly a pun on her family name, del Giocondo. Our word "jocund" has the same root as Giocondo[Excerpts from Poliziano's La giostra]

Much has been made about the glance of the Mona Lisa. Already in contrast to the blank stare of the fifteenth century profile portraits, Cecilia Gallerani and the ermine consciously turn towards an unseen presence to our right, perhaps Ludovico her lover, while in the Mona Lisa, she looks consciously at us. This reminds us of the importance of the glance of the lover in Petrarchan poetry. As quoted above, Petrarch wrote: "you linger around bright eyes whose loving sting pierces me so." Or, for example, Poliziano in his La giostra writes:

| From her eyes there flashes a honeyed calm in which Cupid hides his torch; wherever she turns those amorous eyes, the air about her becomes serene. Her face, sweetly painted with privet and roses, is filled with heavenly joy; every breeze is hushed before her divine speech, and every little bird sings out in its own language [XLIV]. |

Central to the thought of Leonardo was the paragone or the competition in the arts. Leonardo staunchly claimed the superiority of sight and painting over poetry and the other arts. In the following excerpts Leonardo makes the comparison between painting and poetry:

| If the poet knows how to describe and write down the appearance of forms, the painter can make them so that they appear enlivened with lights and shadows which create the very expression of the faces. Herein the poet cannot attain with the pen what the painter attains with the brush.

And if the poet serves the understanding by way of the ear, the painter does so by the eye --the nobler sense; but I will ask no more than that a good painter should represent the fury of a battle and that that a poet should describe one and that both these battles be put before the public; you will soon see which will draw most of the spectators, and where there will be most discussion, to which more praise will be given and which will satisfy the more. Undoubtedly the painting being by far the more intelligible and beautiful will please more. Inscribe the name of God and set up His image opposite, and you will see which will be more revered. Painting embraces within itself all the forms of nature, while you have nothing but their names which are not universal as form is. If you have the effects of demonstrations we have the demonstrations of the effects. Take the case of a poet who describes the beauties of a lady to her love and a painter who portrays her; and you will see whither nature will more incline the enamoured judge. Surely the proof of the matter should be allowed to rest on the verdict of experience. |

The latter passage with its reference to a furious battle scene and painting of the "beauties of a lady" was perhaps written while Leonardo was working on the Mona Lisa which was concurrent with his painting of the Battle of Anghiari.

Mona Lisa Images for a Modern World

large ; beforeRaphael, Portrait Study.

Raphael, Double Portrait of Angelo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi Doni, c. 1506.

| Martin Kemp, Leonardo, p. 253: Leonardo was documented as working on a small picture of this subject in 1501, after his return to Florence. The patron was Florimond Robertet, Secretary of State to successive French kings. He appears to have received his picture in Blois in 1507. Technical examination has revealed strikingly complex and similar underdrawings in both versions, indicating Leonardo's direct involvment in making two pictures of this subject. Which went to Robertet is presently unclear. | |