The Making of Early Copies of the French Translation

of Boccaccio's De mulieribus claris

An illuminated manuscript

is a nexus of various branches of medieval studies. This insight underlies

many recent studies of late medieval manuscripts.

Derek Pearsall has written: "...palaeography, codicology and manuscript studies

generally are now more than ever before to be seen as an integral part of the

study of literature and literary history, and vice versa. The fact of their interdependence

becomes clearer and clearer as research advances, and the nature of that interdependence

needs to be similarly clarified." Scholars have emphasized the attention

paid by authors like Guillaume de Machaut and Christine de Pizan to the production

of copies of their texts. The traditional disciplinary boundaries separating

studies of the textual and pictorial contents have been broken down: literary

and art historians alike have explored text-image relationships. With the

advent of codicology, the interests of the art historian and palaeographer

have begun

to merge. Art historians have sought to examine the paintings in manuscripts

not in isolation but as part of an integrated study of a book as a totality.

The appreciation of a manuscript as a product of a carefully conceived plan

and of the coordinated activities of different specialists has led historians

of

the medieval book to explore the social and economic contexts involved in

the book industry.

These perspectives inform this present study which will examine the production

of three early copies of a French translation of Boccaccio's De mulieribus

claris. On September 12, 1401, an anonymous translator completed work on

the French version

, entitled Des femmes nobles et renommées. On New Year's day of 1403,

Jacques Rapondi, a Lucchese merchant established in Paris, presented a copy of

the translation to Philippe le Hardi, the duke of Burgundy. In February of 1404,

Jean de la Barre, receveur general des finances in Languedoc and Guyenne, presented

a copy of the same text to Jean de Berry. Both of these copies are currently

preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris. On the basis of the

Burgundian inventory of 1420, MS fr. 12420 can be identified as the copy given

to Philippe, while the ex libris of the Duke of Berry written by his secretary,

Jean Flamel, appears at the beginning of MS fr. 598 and the signature of Jean

de Berry appears on folio 161. A third early copy of the text is in the Bibliothèque

Royale in Brussels (MS 9509). Although this manuscript appears in inventories

of the Burgundian collection, its date and original ownership are unclear.

Meiss has dated the Brussels' manuscript to between 1410-1415 on the basis

of his assessment

of the style of the miniatures. Although the more limited miniature cycle

of this manuscript distinguishes it from MS fr. 12420 and MS fr. 598, examination

of the manuscript reveals its close association to the other copies.

These manuscripts

are significant for both the intellectual and art historian. They are early

testament to the French interest in the writings of "modern" authors,

especially the works of Boccaccio. The heavy emphasis Boccaccio places

on the mythology and history of the ancient world apparently appealed to

the growing "humanist" interests

within the intellectual circles associated with the French court at the

beginning of the fifteenth-century. Bella Martens pointed to the art historical

importance

of the miniatures in these books in the developing naturalism of early

fifteenth-century French manuscript illumination. She attributed the miniatures

in MS fr. 12420

and MS fr. 598 along with a group of other manuscripts to an artist she

dubbed the Master of 1402. More recent assessments by Millard Meiss and

Patrick de Winter,

while agreeing with Martens on the stylistic importance of the miniatures,

have seen that each manuscript is dominated by a distinct artistic personality.  With

the exception of a few miniatures, Meiss has attributed the miniatures

of MS fr. 12420 to an artist he has called the Coronation Master after

a representation

of the Coronation of the Virgin this artist added to a copy of the Golden

Legend (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 242).

In turn, Meiss used the miniatures of MS fr. 598 as the eponymous manuscript

on which to base the corpus of an artist he named the Master of Berry's

Cleres Femmes. After earlier attributing both manuscripts to the same

group of miniaturists,

de Winter has subsequently come to agree with Meiss's attribution, although

he identifies the principal artist of MS fr. 12420 after this manuscript

as the

Maître du livre Des Femmes nobles et renommées de Philippe

le Hardi. De Winter has distinguished three distinct hands in the miniatures

of MS fr.

598. Meiss has attributed the miniatures of MS 9509 to an artist related

to his Master of Berry's Cleres Femmes.

With

the exception of a few miniatures, Meiss has attributed the miniatures

of MS fr. 12420 to an artist he has called the Coronation Master after

a representation

of the Coronation of the Virgin this artist added to a copy of the Golden

Legend (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 242).

In turn, Meiss used the miniatures of MS fr. 598 as the eponymous manuscript

on which to base the corpus of an artist he named the Master of Berry's

Cleres Femmes. After earlier attributing both manuscripts to the same

group of miniaturists,

de Winter has subsequently come to agree with Meiss's attribution, although

he identifies the principal artist of MS fr. 12420 after this manuscript

as the

Maître du livre Des Femmes nobles et renommées de Philippe

le Hardi. De Winter has distinguished three distinct hands in the miniatures

of MS fr.

598. Meiss has attributed the miniatures of MS 9509 to an artist related

to his Master of Berry's Cleres Femmes.

The studies, to date, have focused primarily on examinations of the style

and iconography of the miniatures. Little consideration

has been given to other aspects of the making of these books, most

notably

to the

copying of the text and the secondary decoration. These issues will

be the focus of this

paper, which will examine the discrete stages of the production of

the books from the laying out of the page and the scribal work, through

the

secondary

decoration, to the creation of the miniature cycles. What this examination

will reveal is

that the manuscripts are closely linked in each of these stages. The

connections go beyond general similarities based on standardization

of book making

practices. We will see that some of the same scribes and decorators

were active in each

manuscript. Although I agree with Meiss and de Winter that the miniatures

were created by distinct artisans, an assessment of the relationship

of the miniatures

to the text suggests that the miniaturists were not working independently

but worked under the supervision of a planner. The implications of

these connections

between the manuscripts in their various stages of production suggest

that they represent a veritable first edition of this new text.

THE SCRIBAL ACTIVITY

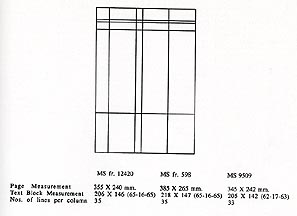

Before the scribes could have begun their work, the lay-out or mise-en-page needed to be defined. All three copies have nearly identical lay-outs, with a two column format and similar ruling patterns. In both MS fr. 12420 and MS fr. 598, there are 35 rows of text per column, while in MS 9509 there are only 33 rows. The measurements of the text blocks in the respective manuscripts although not identical are similar. In laying out the manuscript, it was decided to have allowed between 11 and 14 lines for a miniature and between 4 and 6 lines for an initial to introduce each new text. The type of script to be used also needed to be decided. All three manuscripts are written in the same script, gothica textualis.

The striking similarities in the lay-outs of the three manuscripts

could reflect the standardization of manuscript making practices,

and not necessarily

a direct

relationship in their production. Many of the similarities

noted above can be found in a large number of other books produced

in Paris at

the same time.

Similar

lay-outs are found in copies of texts like the Bible

historiale (e.g. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale,

MS fr. 159), the Livre

des propriétés

des Choses (e.g. Brussels, Bibliothèque royale,

MS 9094), and the Légende

dorée (e.g. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale,

MS fr. 242).  The choice of this mise-en-page for the Boccaccio

text

was probably intended

to place

it in the context of the clerkly tradition of authoritative

texts to which

these

other texts belong. The miniatures introducing the Dedication

and Prologue show Boccaccio dressed as a cleric thereby

attesting

to

the author's

link to the tradition

of Classical and Christian auctores.

The choice of this mise-en-page for the Boccaccio

text

was probably intended

to place

it in the context of the clerkly tradition of authoritative

texts to which

these

other texts belong. The miniatures introducing the Dedication

and Prologue show Boccaccio dressed as a cleric thereby

attesting

to

the author's

link to the tradition

of Classical and Christian auctores.

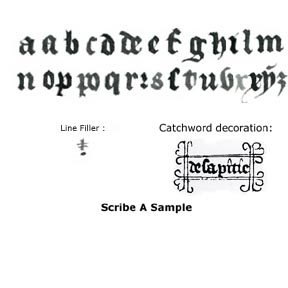

Closer examination of the scripts of the manuscripts reveals

the work of three distinct scribes. This identification

is based on

three different

criteria: general aspect of the scripts, particular letter

formations,

and general

scribal habits.  The

general aspect of the script of the scribe here designated

as A is very regular and controlled with the

letters being

comparatively

widely

spaced. Among

the distinguishing letter formations, the descender of

this copyist's "g" generally forms a long,

fluid curve going off to the left. The letter "y" generally

has a faint, hair-line descender trailing down to the left,

and this letter is

characteristically

dotted with a short stroke that ascends from the left to

the right. As a scribal habit, Scribe A frequently fills

the empty

space at

the end

of a

line of text

with a faint vertical stroke crossed by horizontal dashes.

The framing device for catchwords appears

regularly and

is virtually

a

signature for Scribe A's work.

The

general aspect of the script of the scribe here designated

as A is very regular and controlled with the

letters being

comparatively

widely

spaced. Among

the distinguishing letter formations, the descender of

this copyist's "g" generally forms a long,

fluid curve going off to the left. The letter "y" generally

has a faint, hair-line descender trailing down to the left,

and this letter is

characteristically

dotted with a short stroke that ascends from the left to

the right. As a scribal habit, Scribe A frequently fills

the empty

space at

the end

of a

line of text

with a faint vertical stroke crossed by horizontal dashes.

The framing device for catchwords appears

regularly and

is virtually

a

signature for Scribe A's work.

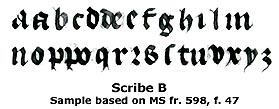

In

contrast to the work of Scribe A, Scribe B's script is smaller, more compact,

and angular. The letter "y" used by this scribe

can easily be distinguished from that of Scribe A by

the hairline descender which loops upwards to the right and the stroke

above which descends from the left

to the right. This scribe's "g" has a descender

which is frequently joined with the upper part of the

letter and

is placed off-center to

the right. Scribe B fills out empty spaces at the end

of lines with a pronounced

minim

stroke crossed by a dash and a dot beneath it.

In

contrast to the work of Scribe A, Scribe B's script is smaller, more compact,

and angular. The letter "y" used by this scribe

can easily be distinguished from that of Scribe A by

the hairline descender which loops upwards to the right and the stroke

above which descends from the left

to the right. This scribe's "g" has a descender

which is frequently joined with the upper part of the

letter and

is placed off-center to

the right. Scribe B fills out empty spaces at the end

of lines with a pronounced

minim

stroke crossed by a dash and a dot beneath it.

The

work of Scribe C has the appearance of being more fluid and more hastily

written than that of the other

scribes. The "y" has

a hairline dash which ascends from the left to the right. This copyist's letter "s" is

typically closed with the lower part being more pronounced. The "a" created

by this scribe is characteristically closed. Period

marks, especially if they appear at the end of a line,

have pronounced

hairline

tails. Like Scribe

A,

Scribe C decorates his catchwords with distinctive

decoration which is again almost

a signature for this scribe's work.

The

work of Scribe C has the appearance of being more fluid and more hastily

written than that of the other

scribes. The "y" has

a hairline dash which ascends from the left to the right. This copyist's letter "s" is

typically closed with the lower part being more pronounced. The "a" created

by this scribe is characteristically closed. Period

marks, especially if they appear at the end of a line,

have pronounced

hairline

tails. Like Scribe

A,

Scribe C decorates his catchwords with distinctive

decoration which is again almost

a signature for this scribe's work.

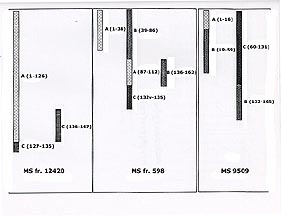

The work of these three scribes can be found in more than one copy of the Boccaccio text. Scribe A and Scribe C worked on all three copies, while Scribe B limited activity to MS fr. 598 and MS 9509. Usually the scribes were responsible for the rubrics and running-titles on pages which they transcribed, but exceptions suggest the distinction in stages between the transcription of the text and the addition of rubrics and running-titles. In MS fr. 598, the rubrics and running-titles in Scribe B's portions were written by Scribe A, while in MS 9509, Scribe C transcribed the rubrics and running-titles for Scribe A's stint.

Closer examination of the division of labor between

these scribes in relationship to the physical structure

of

the manuscripts

gives important

insights into

the production of these books. Two types of scribal

break are evident. The first

type is represented by instances where there is

a change in scribes in the middle of a gathering or even between

a recto

and verso of

a leaf.

Such breaks

suggest

consecutive copying with one scribe picking up

where another left off. The second type is represented by

instances where

there is a

break

in scribes after a short

gathering not containing the standard eight leaves,

or where there is a break

at the beginning of a gathering which introduces

a new text. This type of break suggests the division

of the

text into separate

scribal

units

which

could have

been distributed to the various copyists who could

have worked concurrently on the different scribal

units.

Diagramming these two types of scribal breaks gives

a better picture of the production of these

manuscripts. In the case

of MS fr. 12420,

Scribe A

was responsible for the whole manuscript up

to the recto of

folio 127.

Scribe C was responsible for the verso of this

leaf and the remainder of the gathering.

Significantly this break occurs in a gathering

before a short quire of six leaves (fols. 130-135)

completing

a

scribal unit.

Scribe C

was responsible

for the entirety

of the next scribal unit which extends from

folio 136 to folio 167, the end

of the manuscript. This suggests that Scribe

C actually began activity with folio

136 and worked concurrently with Scribe A who

was completing a stint, and then for some reason Scribe

A suspended

work with Scribe C completing

the

unit, in

all probability after the last scribal unit

had been completed .

Diagramming these two types of scribal breaks gives

a better picture of the production of these

manuscripts. In the case

of MS fr. 12420,

Scribe A

was responsible for the whole manuscript up

to the recto of

folio 127.

Scribe C was responsible for the verso of this

leaf and the remainder of the gathering.

Significantly this break occurs in a gathering

before a short quire of six leaves (fols. 130-135)

completing

a

scribal unit.

Scribe C

was responsible

for the entirety

of the next scribal unit which extends from

folio 136 to folio 167, the end

of the manuscript. This suggests that Scribe

C actually began activity with folio

136 and worked concurrently with Scribe A who

was completing a stint, and then for some reason Scribe

A suspended

work with Scribe C completing

the

unit, in

all probability after the last scribal unit

had been completed .

In MS fr. 598, three distinct scribal units

can be defined. Scribe A was again responsible

for

the beginning

of the

manuscript. Here

this copyist's

first stint

was only the first 38 leaves. While Scribe

A was working on the first scribal unit,

Scribe B probably

began

the next unit

extending from

folio 39 to

folio 135. For some reason Scribe B suspended

activity on this unit on folio 86,

and then likely began work on the last scribal

unit extending from folios 136-162.

Scribe A, picking up for Scribe B in the

second scribal unit, was responsible for folios 87-112r,

while Scribe

C completed

this scribal

unit (fols.

112v-135). In MS 9509, there are only two

scribal units. Scribe A and Scribe B collaborated

on the first unit extending from folios 1-59,

with Scribe A responsible for only the first

18 folios.

While Scribes

A and

B were working

on this first

unit, Scribe

C probably began the second unit, transcribing

folios 60-131, while Scribe B reappears on

folio

132 and completes

the

manuscript (fols.

132-165).

Dividing a text up into discrete scribal

units with different scribes working concurrently

expedited the production

of a book. Comparing

the length of

the scribal units gives a rough estimate

of

the relative

amount of time it took to

transcribe the different copies of the

text. For example, the amount of time it took to

produce MS fr. 12420

corresponds to the length

of the first

textual

unit, assuming, as argued above, that the

first and second units were transcribed

concurrently. The amount

of time

it

took to produce

MS

fr. 598 is determined

by the second unit. This again assumes

that this unit was begun at the same time as the

first

unit,

and that

the

third unit

was written

concurrently

with the

second. For MS 9509, the estimate is based

on the second unit. Since the first unit

in

MS fr.

12420

is 135 leaves

and the

second unit

in MS fr.

598

is composed

of 97 leaves, it took 72% of the time to

transcribe MS fr. 598 as opposed to MS

fr. 12420. Comparably,

MS 9509,

which

has a longest

unit of 106

leaves, took roughly 79% as long to write as

MS fr. 12420. Recent studies allow us to conjecture

an approximate

number

of days it

took to complete

the scribal

work on the respective

manuscripts. Donal Byrne, in a study of a Sallust

manuscript in Geneva, interpreted a set of

roman numerals at the

bottom of leaves to be

records of the days

it took to write the manuscript. He concluded

that the scribe completed between 3 and 3.5

leaves per

day. Since

this manuscript

is similar

to the Boccaccio

manuscripts

in format and script, the scribal work of MS

fr. 12420 could have taken between 38 and 45

days, that

of MS

fr. 598 between

28 and 32

days,

while that of

MS 9509 between 30 and 35 days.

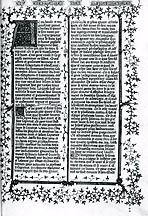

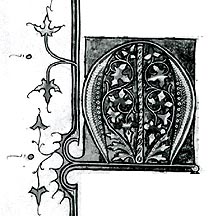

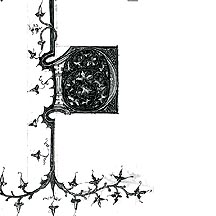

THE SECONDARY DECORATION

The conclusions reached in the study of

the scribal activity are closely paralleled

in

an examination

of the secondary

decoration. The decorative

plan of the manuscripts,

like the lay-out of the page, reflects

the standardization of the

Parisian book industry. Each new text

is introduced by a large gold ground foliate

initial.

Along the margin adjacent to the large

initial runs a bar staff with painted

and gold rinceaux

sprouting

along

its

length and

at the top

and bottom

of the page. Dentelle paragraph marks

appear in the body of the text. This decorative

plan can be found in a number of books

produced in Paris during this period.

Closer

examination reveals the significant relationships between the three copies

of the text. I have

demonstrated elsewhere the ability to isolate

the contributions

of individual decorators. Although

unity and coherence of decorative

plans were

essential concerns for

decorators, a division of

labor can

be articulated

on

the basis of identifying distinct

repertoires of motifs and characteristic treatments

of decorative components.

Such an

examination of the

decoration of the Boccaccio

manuscripts reveals the work of six

distinct decorators.

Of

the decorators, the one here labelled

as

the A Decorator is

clearly

the finest.

His work is distinguished by the

delicacy of the treatment of the

various decorative components, most

apparent in the white highlighting

of bodies of the gold ground

foliate initials and of the dentelle

paragraph marks and line endings.

This delicacy is also apparent in

the thin pen line used in the stems

and tendrils of the penned

line rinceaux and the outlines of

the initials and of the painted rinceaux

leaves.

Closer

examination reveals the significant relationships between the three copies

of the text. I have

demonstrated elsewhere the ability to isolate

the contributions

of individual decorators. Although

unity and coherence of decorative

plans were

essential concerns for

decorators, a division of

labor can

be articulated

on

the basis of identifying distinct

repertoires of motifs and characteristic treatments

of decorative components.

Such an

examination of the

decoration of the Boccaccio

manuscripts reveals the work of six

distinct decorators.

Of

the decorators, the one here labelled

as

the A Decorator is

clearly

the finest.

His work is distinguished by the

delicacy of the treatment of the

various decorative components, most

apparent in the white highlighting

of bodies of the gold ground

foliate initials and of the dentelle

paragraph marks and line endings.

This delicacy is also apparent in

the thin pen line used in the stems

and tendrils of the penned

line rinceaux and the outlines of

the initials and of the painted rinceaux

leaves.

The

high quality of the A Decorator becomes immediately apparent

by comparing

the work by this craftsman to that

of the B Decorator,

whose white highlighting of the initials and

of the dentelle paragraph marks

and line endings is more simplified in

the repertoire of decorative

motifs. The painted lines lack

the control and delicacy of those of

the A Decorator. The pen line of

the B Decorator is thicker and

lacks the subtlety of that of

the A Decorator. This can be seen

in the more angular cusps created

by the ink outlining of the initials,

and the less fluid stems and tendrils

of the penned

line rinceaux.

The

high quality of the A Decorator becomes immediately apparent

by comparing

the work by this craftsman to that

of the B Decorator,

whose white highlighting of the initials and

of the dentelle paragraph marks

and line endings is more simplified in

the repertoire of decorative

motifs. The painted lines lack

the control and delicacy of those of

the A Decorator. The pen line of

the B Decorator is thicker and

lacks the subtlety of that of

the A Decorator. This can be seen

in the more angular cusps created

by the ink outlining of the initials,

and the less fluid stems and tendrils

of the penned

line rinceaux.

The general appearance of the work of the C Decorator is finickier and more cramped (Fig. 15), most apparent in the pen line employed by this decorator. The stems of the penned line rinceaux are frequently broken up by curls and dashes, while the outlining of the painted rinceaux creates more pronounced cusps.

The tendrils projecting from the stems of the penned line rinceaux are signatures for the work of the D Decorator (Fig. 16). These are formed by a pronounced curl usually followed by a loose "S" shaped curve. This decorator frequently includes a dragon projecting from the top of the bar staff.

The

general aspect

of the E Decorator

suggests a rapidity of execution, perhaps

most apparent in

the tendrils of the penned

line rinceaux generally

formed by a comma stroke

followed by a quick "2" shape.

Clusters of gold

balls with the

distinctive

tendril decoration

frequently appear

in the borders

associated with

this hand.

The E Decorator

also creates denser

clumps

of painted

rinceaux from

which frequently

projects a gold

tongue

shape.

The

general aspect

of the E Decorator

suggests a rapidity of execution, perhaps

most apparent in

the tendrils of the penned

line rinceaux generally

formed by a comma stroke

followed by a quick "2" shape.

Clusters of gold

balls with the

distinctive

tendril decoration

frequently appear

in the borders

associated with

this hand.

The E Decorator

also creates denser

clumps

of painted

rinceaux from

which frequently

projects a gold

tongue

shape.

The F Decorator typically adds trilobed painted leaves in a concave space created by the bar staff adjacent to initials. The decorator also increases the number of cusps in the ink outlining of the staffs and initials. The gold leaves of this decorator are also typically thinner than those of the other decorators. The concave space left on the right side of paragraph marks are distinctive of this decorator's contributions.

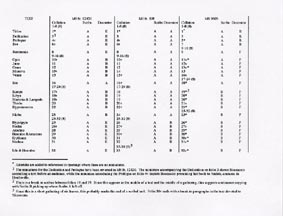

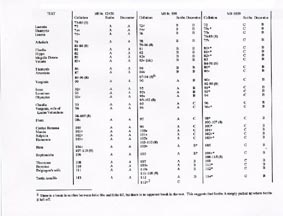

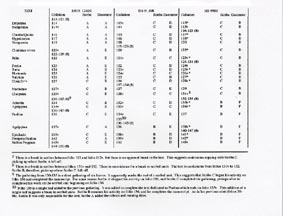

The following tables identify the contributions

of

these distinct decorators:

The decoration of MS fr. 12420 was the responsibility of the A, B, and E Decorators, while five decorators worked on MS fr. 598 ( A, B, C, D, and E Decorators) and two decorated MS 9509 (B and F Decorators). Only the B Decorator worked on all three copies of the text, while the A and E Decorators worked on both MS fr. 12420 and MS fr. 598. The three other decorators (C, D, and F Decorators) contributed to only one of the copies. The collaboration of some of the decorators in multiple copies of the text reaffirms the conclusion reached in the discussion of the scribal activities that the different manuscripts are linked in their process of production. Since there is no correlation between the work of specific scribes and decorators, there is no evidence to conclude that any of the scribes also acted as a decorator.

The

division

of

labor

in

the

decoration

gives

a

better picture

of

the

production

of

the

books.

In

the

majority

of

cases

a

single

decorator

was

given

responsibility

for

the

decoration

of

a

gathering. It

seems,

especially

in

the

early

stages

of

production,

groups

of

gatherings

were

turned

over

to

a

decorator

at

a

single time.

For

example,

in

MS

fr.

598,

the

A

Decorator was

given

the

first

three

gatherings,

while

the

B

Decorator

was

given

the

next

nine

gatherings.

The

decorators

could

have

worked

concurrently

on

their

stints.

In

the

latter

portions

of

MS

fr.

598,

the

division

of

labor

is

more

complex.

With

the

gathering

beginning

on

folio

95,

decorators

appear

to

have

been

given

individual

gatherings

with

the

C,

B,

and

D

Decorators

each

being

given

a

single

gathering.

The

pattern

in

MS

fr.

598

becomes

more

complicated

with

the

gathering

beginning

on

folio

119

where

as

many

as

three

different

decorators

participated

in

the

decoration

of

an

individual

gathering.

Here

the

division

of

labor

is

by

bifolio.

It

is

noteworthy

that

in

these

latter

portions

of

MS

fr.

598

appear

the

only

contributions of

our C

and D

Decorators

in the

Boccaccio

manuscripts.

This

suggests

that

the

makers

of MS

fr. 598

were

under

pressure

to complete

the

manuscript

as soon

as possible,

necessitating

the

more

complicated

pattern

of the

division

of labor

and the

appearance

of these

other

decorators

who were

apparently

called

in to

help

speed

up the

process

of production.

These

conclusions

parallel

those

we

have

already

reached

in our

discussion

of the

division

of labor

in

the scribal

activity.

In

contrast to

MS fr.

598, the

division of

labor of

MS 9509

is much

simpler. Here,

only two

decorators participated

with each

apparently being

given groups

of gatherings

at a

single time.

The way

the B

and F

Decorators leap

frog through

the manuscript

suggests that

they were

working concurrently

with each

other and

with the

scribes. Groups

of gatherings

could be

parcelled out

to the

decorators as

the scribes

completed their

work on

them. The

decoration of

MS fr.

12420 presents

an intermediate

case between

the apparently

hectic pace

of MS

fr. 598

and the

leisurely one

of MS

9509. The

three decorators

divided their

labor by

groups of

gatherings in

the early

stages of

production. It

is only

with the

gathering beginning

on folio

114 that

a more

complex pattern

becomes apparent

with decorators

dividing the

labor by

bifolios.

THE

MINIATURE CYCLES

As

noted earlier,

MS fr.

12420, MS

fr. 598,

and MS

9509 were

dominated by

distinct artistic

personalities. In

contrast to

the other

stages of

production, there

is no

evidence of

individual miniaturists

working on

more than

a single

copy of

the Boccaccio

text. Acknowledging

this, the

striking similarities

in the

selection and

composition of

scenes in

corresponding miniatures

in the

various copies

of the

text needs

to be

explained. Instead

of concentrating

on the

issue of

miniature style,

the focus

here will

be on

a comparison

of the

different miniature

cycles and

their relationship

to the

texts they

illustrate.

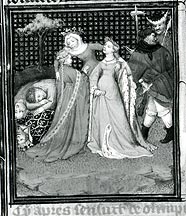

The

relationship between

text and

image can

be demonstrated

by considering

the illustrations

associated with

the story

of the

infamous Olympias,

wife of

Philip of

Macedon and

the mother

of Alexander

the Great

(Figs. 1,

2, & 3).

The miniatures show

the crowned figure

of Olympias, wearing

a wimple and

being supported

by two women,

while armed

figures approach

Olympias. This

illustrates Boccaccio's

account of how

the jailed

Olympias, aware

of the approaching

executioners, prepared

herself and with

the assistance

of two servants

stood fearlessly

to face her death.

The miniatures include

a pile of bodies

among which

can be seen

a crowned figure.

This detail

demonstrates how

different moments

in the narrative

are combined.

Earlier in

the text, Boccaccio

tells how Olympias,

who had been

spurned by her

husband Philip

for committing adultery,

had

urged Pausanias,

her lover,

to kill Philip.

After Pausanias

had been executed

for the assasination,

Olympias had

his body placed

over the remains

of King Philip.

The three

miniatures, thus,

visualize the story

in the same

way even to the

point of

conflating different

episodes of the

account. But

comparison

of corresponding figures

in

the different

manuscripts suggests

no evidence

of dependence on a

common visual

model. The correspondences

evident

in the

Olympias miniatures are

characteristic of the

relationship

between the miniature

cycles in the three copies.

Even

when the

text does

not articulate

a particular

scene, the

conception of

the miniatures

is the

same. This

is exemplified by the

illustrations opening

the text

dedicated to

Minerva. The text enumerates Minerva's

various gifts: the art of wool (how it should be cleaned, softened

with a comb, placed on a distaff and spun with the fingers, and

woven); the pressing of olives

for oil; the invention of the cart; how to make iron weapons; the

use of armor; the strategy for soldiers and rules of battle; the

use of numbers; and the creation

of the flute. Each miniature shows Minerva seated on a throne with

figures illustrating her various gifts encircling her. Comparing

the list of gifts enumerated by the

text to those illustrated reveals significant variations. None

of the miniatures illustrate either the invention of the cart or

the strategy and rules of battle.

The miniatures conflate the creation of iron weapons and the use

of armor by showing a man beating a helmet on an anvil, and all

visualize the use of numbers

by showing a money-changer at his counting desk. There are differences

between the miniatures. In MS fr. 12420, Minerva is represented

without a crown and halo,

and

the art of wool is represented

by a single figure separating

wool. In contrast, both

MS fr. 598 and MS 9509

represent Minerva as crowned

and haloed,

and the art of wool is

represented by a woman

combing wool and a man

weaving.

These differences,

however, do not

override the striking

similarities between

the miniatures, and,

as will be

argued later,

these variations

possibly reflect

a revision in the

program

of the

illustrations.

Differences

in the

placement and

poses of

the figures

in the

corresponding miniatures

argue against

the use

of a common visual

model. The

relationship between

the different

miniature cycles

is best

explained by

their dependence

on a

common written

model. It

was a

common practice

to provide

miniaturists with

written directions

for miniatures.

In margins

adjacent to

miniatures in

a number

of manuscripts

erased instructions

can be

found. We

also have

the famous

case of

the pictorial

program that

Jean Lebègue wrote for the illustration of Sallust's Conspiracy

of Catiline and Jugurthine War. Another example is presented by what Gilbert

Ouy has identified as a maquette or manuscript model for luxury copies of the

text. This is a paper copy of Honoré Bouvet's

Somnium

super

schismatis, where

marginal notes

provide instructions

for the addition

of miniatures.

Although

in most

cases the

miniatures correspond

well with

the texts

they illustrate,

cases can

be found

where particular

miniatures are inconsistent with

the text

and disagree

with other

versions of

the pictorial

cycle. An

example of

this is

the miniature

in MS

fr. 598 accompanying

the

story of

Polyxena. The

text describes

how the

son of

Achilles, Neoptolemus,

revenges his

father's death

which had

innocently been

caused by

Polyxena.

The

story recounts

how Neoptolemus

slays Polyxena

by the

tomb of

Achilles. The

miniatures in

both MS

fr. 12420

and MS

fr. 598

show

the

son wielding

a sword

over the

figure of

Polyxena who

kneels by

a tomb.

In MS fr. 598,

however, instead

of showing a closed

tomb which

would have

been consistent

with the text,

an empty

tomb is depicted

with its lid

ajar. Without knowledge

of the

text it would

be natural to assume

that the

coffin was intended

for Polyxena.

We can imagine

this type

of assumption being

made by a

miniaturist who did

not consult

the text but followed

instructions that

called for Polyxena

to be represented

kneeling by a tomb.

The

miniature of

Veturia in

MS fr.

12420 presents

another instance

of a

miniaturist's probable

misinterpretation of

written instructions.

The narrative

tells how

Veturia's son,

Coriolanus, had

been exiled

from Rome

and fled

to the

Volscians. In

time, he

became the

commander

of

the Volscian

army which

he led

in a

war against

his native

Rome. After

Volscian victories,

the

Romans

sent three

embassies to

Coriolanus

to

sue for

peace. In

each case,

Coriolanus rebuffed

the

Roman

appeals. The

Roman matrons

turned to

Veturia

in

hopes that

she

could

persuade her

son. Veturia,

along with

Coriolanus' wife

and his

children, went

to the

Volscian camp,

and there

made an

impassioned appeal

to

Coriolanus.

In general

terms, all

three miniatures

visualize the

confrontation between

Veturia

and

Coriolanus in

the

same

way. The

miniatures are

divided

in

two groups,

one showing

Coriolanus before

his army

and the

other having

Veturia as

the principal

figure.

However,

MS fr.

598

and

MS 9509

are much

closer to

the

details

of the

narrative.

The

text describes

Veturia

as being

old and specifies

that

she was

accompanied by Coriolanus'

wife

and his children.

While

MS fr.

598

and MS

9509 are consistent

with

the

text

in these

details, MS fr.

12420 does

not represent Veturia

clearly

as an

older woman

and her companions

are not clearly

specified as

Coriolanus'

wife

and

children.

But most

significantly, the miniature

in

MS fr. 12420

misinterprets the confrontation

between

Veturia and Coriolanus.

It

is Veturia's

speech which

is

the

central

point of the

account. In both

MS fr. 598 and

MS 9509, the gestures

indicate

that

Coriolanus is listening

to

his mother's

appeal.

In

these miniatures,

Veturia uses

a

pointing

gesture while

Coriolanus' hands

are raised with

his palms placed

outwards, the

conventional gesture

of

someone

listening. In the

case

of

MS fr. 12420,

however,

the

gestures are reversed.

Coriolanus

is

shown ticking

points off on

his fingers, while

Veturia has her

hands raised

as if listening

to Coriolanus' speech.

Anyone

familiar

with the text

would

not

make

this critical

error. Again,

a miniaturist misinterpreting

written

instructions or imprecise

instructions

explain

such

inaccuracies. An

instance like this

strongly

argues against

the possibility mentioned

by others

that the miniatures

of the later

copies of

the text

were based

on the miniatures

of MS fr. 12420.

Again,

the dependence on a

common model,

verbal as opposed

to visual, is the

most satisfactory

explanation.

Although

misinterpretations

of

verbal instructions

can account

for many

of the

inconsistencies between

the different

miniature cycles,

there are

instances where

differences do

occur between

corresponding miniatures

which can

not be

explained by

miniaturists misrepresenting

the

instructions. This

is exemplified

by the

miniatures in

MS fr.

12420 and

MS fr.

598 which

accompany the

story of

Opis.

In MS fr. 12420,

Opis

sits in

a building with

three men kneeling

before her,

while in MS

fr. 598 Opis,

seated in a

temple, gestures

to three statues

placed on pedestals.

Comparison to the

text suggests

that both

miniatures are consistent.

The text

tells how an

image of Opis

was brought to

Rome,

and

was placed in a

noble temple.

The Romans

and Italians honored

the image

for many years

in a variety

of manners and ceremonies.

This

clearly explains

the miniature in MS

fr. 12420,

while earlier

in the text,

it is noted

that the

fame of Opis

is largely

due to her

rescue of her

three

sons,

Jupiter, Neptune,

and Pluto, and their

father

Saturn from

Titan's plans

to kill them.

This linking

of the veneration

of Opis with

that of her

sons is

represented in MS

fr. 598 by having Opis

gesture

to the three

statues, presumably

representing Jupiter,

Neptune, and Pluto.

MS fr. 598 image is not available |

Another

example of

this type

of disagreement

between the

miniature cycles

is represented

by the

second to

last miniature

in the two Paris

manuscripts.

The story of Camiola

tells how after

a sea battle

a certain Roland

was held

as a prisoner.

While Roland's

brother refused

to pay the ransom,

Camiola, a woman

of great wealth,

took pity

on Roland languishing

in prison. She realized

to have him released

she needed

to marry him

and pay the

ransom. The text

tells how Camiola

secretly sent

someone to Roland

to seek

his consent to her

proposal. With

his approval,

Roland and Camiola

were married

by proxy through

the mediation

of a procurator

with the

pledging of

a ring. Camiola

immediately sent

the ransom of two

thousand ounces

of silver to Roland

to have him

released. The

text does

not indicate

that Camiola

and Roland met until

after they

were married

and the ransom

had been paid.

The miniature of MS

fr. 12420

represents Roland

inside

the

prison holding

the hand of

Camiola who stands

outside while

a servant offers

the ransom

to another

man.

Although disagreeing

with the

letter of the

text which

refers to Camiola

and Roland

being married

by proxy, this

miniature is still

consistent with

the spirit of the

text with

the joining

of hands signifying

the marriage

while Roland

was in prison.

In the case

of MS fr.

598, the miniature

is much more

consistent

with

the letter

of the

text.

In

this illustration

Camiola is

represented standing

alone on

the right

side

of the miniature

while her servant,

holding the

ransom offers

Camiola's

proposal

to Roland

inside

the prison.

Since

the Opis

and Camiola

miniatures are

consistent to

at least

the spirit

if not

the letter

of the

text, the variations can

not be

attributed to

miniaturists misinterpreting

verbal

instructions. Also

our knowledge

of book

making practices

suggests that

it would

be extremely

unlikely that

the miniaturists

made these

revisions independently.

These variations

most probably

reflect a

revision in

the pictorial

program. One

can imagine

a planner,

once MS

fr. 12420

was completed,

deciding to

make minor

revisions in

the pictorial

program. Being

aware of

the inconsistency

between the

text and

miniature in

the Camiola

miniature in

MS fr.

12420, he

could have

revised his

instructions to

produce the

corresponding miniature

in MS

fr. 598.

At the

same time,

the planner

might have

made minor

revisions in

other miniatures.

The crown

and halo

could have

been added

to the

Minerva miniature

at the

same time

adding in

the same

miniature the

woman combing

wool and

the man

weaving. The

type of

revisions in

miniature cycles

found in

the Boccaccio

manuscripts parallels

the variations

Sandra Hindman

has identified in her analysis

of the early copies of Christine de Pizan's Epistre

Othéa.

As Hindman's

study

clearly

reveals,

miniaturists

did not

work independently,

but worked

under close

supervision.

Before

leaving

the

miniature

cycles,

I would

like

to

introduce

a

possible

example

of how

the illustrations

enhanced

a

reader's

understanding

of the

text.

This

is suggested

by Christine

de Pizan's use

of

these

manuscripts.

It is

well

known

that

Boccaccio's Des

femmes

noble

et renommées served as a principal source

for Christine's Livre

de

la

Cité des Dames, and Hindman has already determined

how Christine used miniatures in the Boccaccio manuscripts in the creation of

the pictorial cycle for her Epistre

Othéa.

At

least

one

example

can

be

identified

where

a

miniature

in

our

manuscripts

was

probably

used

as

a

source

in

Christine's

writings.

This

is

represented

by

the

miniatures

illustrating

the

account

of

Sempronia

which

show

her

embracing

a

man

while

behind

her

are

placed

a

variety

of

string

instruments

(Fig.

16).

The

text

recounts

the

richness

of

Sempronia's

intellectual

accomplishments.

It

notes

her

mastery

of

Latin

and

Greek

and

her

ability

to

write

verses.

She

was

also

an

accomplished

singer

and

dancer,

and

knew

how

to

play

all

instruments

(...Elle

savoit

de

tous

instrumens

jouer....).

Boccaccio

goes

on

to

note

how

Sempronia

used

these

abilities

as

instruments

of

sensuality

and

turned

to

wantonness.

Christine

includes

an

account

of

Sempronia

in

her

Cité des dames. Her account closely follows Boccaccio's listing

of the abilities of Sempronia except for a subtle, but I think a significant

difference. Whereas Boccaccio states that Sempronia was accomplished in all instruments,

Christine is more specific and states that Sempronia "...played all string

instruments so skillfully that she won every contest" (emphasis

added). The only

source of which

I am aware

which specifies

her mastery of string

instruments as opposed

to musical instruments

in general is represented

by the miniatures

of our Boccaccio

manuscripts.

This

suggests that

Christine de

Pizan did not

base her

borrowings

simply

on the text

of Boccaccio,

but she,

as has already

been demonstrated

by Hindman,

had access

to one of the

early

copies

of our French

translation.

Christine-

perhaps

used

both the

text and the miniatures

as

sources for

the

composition

of

her text.

CONCLUSIONS

All

stages

of

production from

the transcribing

of the

text,

through

the painting

of the

secondary

decoration,

to the

creation

of

the miniature

cycles

are

closely interconnected

in the

three earliest

extant copies

of the

Boccaccio

text.

All the

scribes

and

the majority

of the

decorators

collaborated

on multiple

copies, and

that, although

different miniaturists

were responsible

for the

pictorial cycles

in the

respective books,

their work

was apparently

based on

the same,

albeit at

times revised,

written instructions.

Such interconnection

raises important

questions about

the nature

of the

Paris book

industry. Undoubtedly

the various

specialists were

working under

common supervision.

Can it

be determined

who was

responsible for

coordinating production?

The question

of the

working relationship

of the

various makers

also needs

to be

examined. Were

they working

within the context

of

a workshop,

or were they working

independently?

Patrick

de Winter

has speculated

about the

role the

financier Jacques

Rapondi might

have played

in the

creation of

these Boccaccio manuscripts.

De

Winter has

gone as

far as

to say

that, at

least in

the case

of MS

fr. 12420,

Jacques Rapondi

directed the

project, and

he has

suggested that

Rapondi provided

Jean de

la Barre

with the

copy of

the text

which the

latter presented

to Jean

de Berry.

Further study

of the

Burgundian accounts

attest to

Rapondi's frequent

dealings with

the book

industry. Examination

of the

other extant

manuscripts clearly

associated with

Rapondi do

suggest interesting

correspondences. For

example, Scribe

A (Fig.

17) and

Decorators B

(Fig. 17)

and E

(Fig. 18)

contributed to

the production

of the

Livre

des

propriétés des Choses (Brussels, Bibliothèque

royale, MS 9094) which Jacques Rapondi sold to Philippe le Hardi in 1402, while

the A Scribe (Figs. 19-21) and the A (Fig. 19), D (Fig. 20), and E (Fig. 21)

Decorators appear to have collaborated on a copy of Hayton's Fleur

des

histoires

de

la

terre

d'Orient (Paris, Bibliothèque

nationale, MS fr.

12201), known

to be one

of three copies

Rapondi had completed

for Philippe le

Hardi in May

of 1403.

These instances

of repeated collaboration

support de Winter's

conclusion that

Jacques Rapondi

played a central

role in the

production of these

manuscripts, but I

question whether

Rapondi, considering

his other

activities, would

have been directly responsible

for coordinating production.

He perhaps

served as a

financial backer

for the

project, and left

the task of oversight to someone

else.

The

dealings of

another financier

Bureau de

Dampmartin present

possible parallels

to the

activities of

Jacques Rapondi.

Dampmartin served

as the patron of

Laurent de

Premierfait, who,

while living

in Dampmartin's

Paris "hotel", worked

on a French translation of Boccaccio's Decameron. This translation was subsequently

dedicated to Jean de Berry. The inventories of the Duke of Berry's collection

indicates that Dampmartin was an important source for new additions to the library.

François Avril has discussed the role Dampmartin played in the production

of at least one of these acquisitions. The Berry inventory of 1413 refers to

a "livre de Troye la grant" that Jean de Berry bought from Bureau de

Dampmartin in April of 1402. Avril has identified this manuscript as MS fr. 301

in the Bibliothèque nationale which, along with another copy, was copied

from a fourteenth-century Neapolitan manuscript of an Histoire

ancienne

jusqu'a

Cesar now in the British Library (Royal 20.D.I). This London manuscript contains

the following intriguing note on folio 8v: "Ci faut le secont cayer que

maistre Renaut doit avoir, qui baillé à Perrin Remiet pour faire

l'enluminure de l'autre cayer." Avril has convincingly identified the "maistre

Renaut" as Regnault du Montet, an important Parisian "libraire" of

the beginning of the fifteenth-century, and as Avril notes, Perrin Remiet was

an active "enlumineur" in

Paris at the

end of the

fourteenth and

beginning of

the fifteenth-century. As

Avril

has argued, in order

to make copies

of the London

manuscript, it was

unbound so that

different portions

could be distributed

to the scribes

and miniaturists involved

in the project.

Apparently, Regnault

du Montet

served as the

coordinator of

the production of the

copies, and

when the original

manuscript was

being rebound

after the

copies were

completed, the second

gathering was

found to be

missing. Unfortunately

there is no

clear documentary

evidence about

the relationship

between Regnault

du Montet and

Bureau de Dampmartin

in the production

of BN fr. 301.

It has

been assumed

that Dampmartin

purchased the manuscript

from Regnault

du Montet, but considering

the significant

financial outlay

involved in producing

such a manuscript,

the question

should be

raised whether

Regnault du

Montet acted

independently. Did Montet

carry out the

project with

the financial

backing of Bureau

de Dampmartin?

The roles of merchants

like Bureau

de Dampmartin and Jacques

Rapondi as middlemen

between authors

and/or manuscript makers and patrons

deserves closer study.

If

Jacques Rapondi

served as

the financial

backer of

the project,

this leaves

open the

question of

who took

direct responsibility for supervising

production. A

possible candidate

could be

the anonymous

author of

the translation.

Recent studies

of the

activities of

Christine de

Pizan have convincingly demonstrated

the strong

control she

had over

the production

of copies

of her

work. Reno

and Ouy

have demonstrated

that Christine

frequently acted

as a

scribe in

her own

manuscripts, and

Sandra Hindman's

study of

the Epistre

Othéa has convincingly

demonstrated the control Christine had over the creation of miniature cycles

that illustrate her texts. The author of the translation would be the most logical

person to have had the responsibility of devising and then revising the pictorial

program. Study of various copies of Christine's texts shows that she regularly

corrected and revised her work as different examples were produced. As Hindman

has observed, the comparative importance of creating a miniature cycle is suggested

by noting that when we can identify the creator of a miniature cycle it is usually

a highly educated person. For example, Ouy, on the basis of paleographic evidence,

has identified the creator of the maquette of Bouvet's Somnium

super

schismatis as Jean Gerson, the principal Parisian theologian of the early fifteenth-century.

Likewise, the humanist and royal functionary, Jean Lebègue,

devised

the

pictorial

program

for

the

work

of

Sallust.

Add

Rouse and Rouse discussion of Raoulet d'orleans in the Vaudetar bible.

Another

possible

candidate

could

be

one

of the

scribes.

Documents

reveal

that scribes,

or écrivains,

regularly

were given

the responsibility

of coordinating

production.

Here Scribe

A is a possibility.

Scribe A

was responsible

for the beginning

portions

of each copy

of the Boccaccio

text, and

he also completed

the rubrics

and running-titles

for Scribe

B's stints

in MS fr.

598. It is

significant

to recall

that the

work of Scribe

A can be

identified

in the two

other extant

manuscripts

which Jacques

Rapondi provided

for Philippe

le Hardi

(Brussels,

Bibliothèque

royale, MS 9094 and Paris, Bibliothèque

nationale, MS fr.

12201). Since

he was the

sole scribe

of MS fr.

12201 and was

responsible for

the opening portions

of MS 9094,

he was likely

the principal scribe

for these

other projects.

Scribe A could

have been

Jacques Rapondi's

principal contact

with the

book industry.

Having the responsibility of

coordinating the

work of the

different specialists,

Scribe A could

also have

worked with

the anonymous

translator, who

is the likely

candidate responsible

for the creation

and revision of

the written

guides for the miniature cycles.

Another

question which

needs to

be explored

is the

relationship of

the various

makers of

the Boccaccio

manuscripts to

each other. Were the

artisans members

of an équipe , or were they independent craftsmen hired on an ad hoc basis

to make their contributions? The appearance of different miniature styles in

the respective copies suggests that the miniaturists at least were independent,

but what about the relationship of the scribes and decorators? The collaboration

of a number of the makers in other projects for Jacques Rapondi has already been

noted, and the work of these scribes and decorators can be found in a number

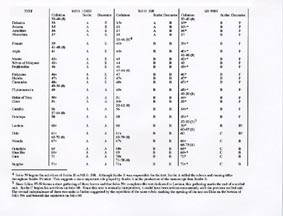

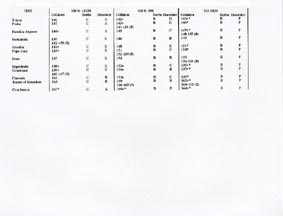

of other manuscripts. Text Figure 4 charts out the appearance of these specialists.

While there are examples of repeated collaboration, there is no consistent pattern

of collaboration. The examples of repeated collaboration probably suggest more

about the common supervision of different projects than the possible existence

of a single workshop. For example, Scribe C and Decorators A and B along with

other specialists shared in the responsibility of creating three copies of the

Bible

historiale (Brussels, Bibliothèque royale, MS 9024-9025; Paris,

Arsenal, MS 5057-5058; Paris, Bibliothèque

nationale,

MS

fr.

159).

These

correspondences

probably

indicate

that

these

manuscripts

were

produced

under

the

guidance

of

the

same

coordinator.

Although

a

more conclusive

answer

about the relationship

of

the

makers

needs

to

await

a

more

detailed examination

of

a

larger

group

of

manuscripts,

the

evidence

to

date

suggests that

the

different

specialists

did

not

work

in

a

shared

workshop,

but

rather

that

they

worked

independently.

Other

study has

suggested that

artisans did

work independently

and were

called in

on an

ad hoc

basis to

contribute to particular projects.

There is

also little

documentary evidence

for the

existence of

large workshops

that would

employ the

number of scribes and

decorators involved in the

production of

the Boccaccio

manuscripts. In

fact, documents

suggest that

workshops were

composed of

members of

a family

with the

addition of

maybe a

couple of

assistants. It

seems that

the book

industry depended

on the

close physical

proximity of

the shops

of the

various practitioners.

It is

well known

that artisans

involved in

book production

lived in

the neighborhood

near the

university, especially

on the

streets around

St. Severin.

The Pont-du-Notre

Dame and

the rue

Neuve de

Notre Dame,

adjacent to

the cathedral,

were also

popular locations

for workshops

involved in

the industry.

The collaboration

of Regnault

du Montet

and Perrin

Remiet in

the production

of copies

Histoire ancienne

jusqu'a Cesar

demonstrates how

the centering

of the

industry in

specific neighborhoods

facilitated the

participation of

several

shops in the

making of individual

manuscripts. Rent

records for Paris

from 1450-51

list as

a previous owner

of a

house on the

rue de la

Parcheminerie a Pierre

Remiot, perhaps

identifiable as Perrin

Remiet. Significantly

this house

was adjacent to one

which had belonged

to Regnault du Montet.

Standardization of

book making

practices such

as types of

scripts and

decoration also

facililated the coordination

of production

shared by independent

shops.

The

manuscript

industry,

thus,

demanded

a clear

articulation

and standardization

of the

discrete

specialties.

The success

of a practitioner

depended

on the ability

to conform

to the

standards of the trade

and to

work

effectively

with

the network

of interdependent

shops.

With

full

awareness

of

the

conjectural

nature

of

the

following

conclusions,

a

hypothetical

account

of

the

process

of

production of the

Boccaccio manuscripts

can be

proposed. Jacques

Rapondi, being

aware of

the growing

interests of

members of

the Valois

family in

such new

texts, could

have served

as the

patron of

the anonymous

translator just

as Bureau

Dampmartin was

the patron

of Laurent

de Premierfait

while the

latter was

producing the

French translation

of the

Decameron. By

giving such

a deluxe

manuscript to

the Duke

of Burgundy

as a

New Year's

present, Rapondi

was aware

that he

would not

only receive

a monetary

gift in

return, but

as a

token of

his allegiance

to Philippe

le Hardi,

such a

gift would

further his

other commercial

interests as

well. This

is implicit

in the

record of

Philippe le

Hardi's gift

of 300

francs to

Jacques Rapondi

for not

only the

presentation of

the Boccaccio

manuscript but

also for "...les bons services qu'il [Jacques Rapondi] lui

faiz chascun jour et espere que face ou temps avenir...." De

Winter

has

already

suggested

that

the

motivation

of

Jean

de

la

Barre

in

giving

a

copy of

the

text

to

Jean

de

Berry

was

directly

connected

to

his

hope

for

a

positive

resolution

of

the

legal

difficulties

he

was

facing.

In

completing

the

translation,

the

anonymous

author in

all

probability

produced

a maquette

comparable

to

the one

Gerson

produced

for the

Bouvet

text.

This model,

possibly

written

on paper,

would

have

provided

the

basic

lay-out

of the

text with

spaces

defined

for the

large

initials and miniatures

that introduce

each account.

In the

maquette's margins

adjacent to

the spaces

designed for

miniatures could

have appeared

the guides

for the

pictorial program.

The author

could then

have either

parcelled out

the work,

or could

have turned

the project

over to

an écrivain, possibly our Scribe A, who would have had the responsibility

of overseeing the work of the different specialists. In either case, the continued

involvement of the author in the production of the different copies is suggested

by the revisions we have observed in the pictorial cycles. The maquette seems

to have been divided into separate scribal units which were distributed to various

scribes who probably worked concurrently. When the writing of a group of gatherings

was completed, they could then be distributed to the decorators. Once the decorators

completed their work, the gatherings could then be given to the miniaturists

along with the pictorial guides. These guides could have been in the form of

the maquette created by Gerson, or they could have been on separate sheets like

those composed by Jean Lebègue

for the Sallust

text. The separate

stages of production

could have

been carried

out

concurrently

so

that

while

the

scribes

were

working

on

the later

portions

of

the

text,

the

decorators

and miniaturists

could

have

already

been

at work

on their

contributions.

Although considering our current state of knowledge significant questions about the nature of the manuscript industry need to be left without conclusive answers, the type of integrated study of the different stages of book production presented in this paper can provide valuable clues to the resolution of these questions. This type of research appears to be particularly rich in its implications. For the literary historian, it can provide a better picture of the creation and production of new texts. The art historian can gain a better understanding of the nature of the creative process involved in painting a new pictorial cycle. The economic historian can gain insights into the workings of a major medieval industry. While the historian can learn much about the role patronage played in the social and political life of the period.