Art Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 213 Assignments

Giotto, Arena Chapel

|

|

|

|

|

|

History:

In 1300, the wealthy Paduan merchant Enrico Scrovegni bought a piece of land on the site of a former Roman arena. Included in the palace that he built on the site was a chapel dedicated to the Virgin of the Annunciation, Santa Maria Annunziata, and the Virgin of Charity, Santa Maria del Carità. Enrico is shown in the fresco of the Last Judgement presenting a model of the chapel to the Virgin:

The family wealth had been amassed by Enrico's father, Reginaldo, whom Dante singled out as the arch usurer in his Inferno. Usury, the lending of money for profit, was considered a sin during the Middle Ages. It is likely that Enrico constructed the chapel as a means to expiate the father's sin. The dedication of the Chapel to the Virgin of Charity, referred to in a document of March of 1304 in which Pope Benedict XI granted indulgences to those who visited "Santa Maria del Carità de Arena," was an obvious choice to disassociate the family from taint of greed and miserliness.

The theme of usury is developed in a number of frescoes in the Arena Chapel. This is most evident in the prominent positioning of the scene of Judas being paid for betraying Christ on the north side of the Chancel Arch adjacent to the altar:

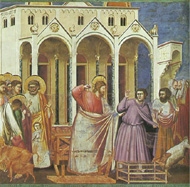

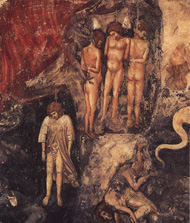

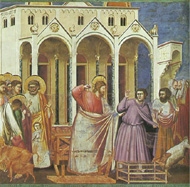

But the theme of usury is also developed in the adjacent image of Christ expelling the merchants from the Temple and the detail of usurers hanging from the their money bags in the Hell scene included in the Last Judgment:

|

|

|

The size and splendor of the Arena Chapel offended the monks of the neighboring Eremitani Church, who lodged a complaint before the Episcopal Curia in Padua. We, thus, can see the Arena Chapel as both a token of Enrico Scrovegni's piety and his contrition for the sins of his father and also as a symbol of his family's status as wealthy merchants who are emulating the aristocracy with the lavish palace and private family chapel. Enrico Scrovegni's seeming conflicting motivations in commissioning the Arena Chapel is brought out in the following passage:

"Among the factors that relate specifically to Enrico Scrovegni are a possible desire to expiate his father's usury and at the same time to make his own expenditure conspicuous; an ambition for status combined with a fear of damnation; a desire, on the one hand, to be regarded as an ascetic devoted to the cult of the Virgin, and, on the other, to secure for himself a fitting property to serve as his personal monument (Source:Diana Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Volumr II: Case Studies, p. 92)."

It is likely that the Chapel was formally consecrated on March 25, 1305, the Feast of the Annunciation. An entry in the records for March 16,1305 of the High Council of Venice documents the lending of tapestries to Enrico Scrovegni on the occasion of the dedication of his chapel.

The earliest reference to Giotto's frescoes in the Arena Chapel is found in an allegorical poem entitled The Documents of Love written by Francesco da Barberino between 1308-1313. The text refers to a figure of Envy that "Giotto painted excellently in the Arena at Padua." This figure of Envy can be identified as one of the series of Virtues and Vices which are located on the bottom register of the Arena Chapel:

Since it was a regular practice in fresco paintings to begin at the top and work down, the Arena Chapel frescoes must have been largely completed by the time Barberino completed his text in 1312-1313, and quite likely they were completed before 1308, the year Barberino left Padua for Provence. Many scholars feel the frescoes were largely completed by the time of the consecration of the chapel in 1305.

Although far from certain, a number of scholars have argued that Giotto was the architect of the Chapel. Whether this was the case or not, the Chapel with its expanse of unbroken wall surface is ideally suited for the fresco cycle.

Technique:

Excerpt from Giuseppe Basile, Giotto : The Arena Chapel Frescoes: (p. 11) Fresco has characteristics and specific requirements that other forms of painting do not have: it requires a fresh coat of plaster which is usable only up to a particular stage of dryness, so that you cannot plaster a greater area than you expect to paint that day. This area --the giornata, or 'day' -- varies according not only to the complexity of the image to be painted and the skill of the painter, but also to the season and the local conditions. You cannot alter or retouch a fresco except by painting over it ( the a secco method) or by cutting out the dry portion of plaster and starting again. The technique demands that you work from the top downward --and usually , though only for the sake of convenience, from left to right. Its use is incompatible with a number of pigments (especially azurite), which are damaged by the main ingredient, lime: consequently, these can only be used in conjunction with a binding medium, which is mixed with the pigment and will cause it to adhere to the plaster. Metal foil --gold leaf, or tin either gilded or covered with silversmith's varnish (meccato), can also be applied only to the dry plaster, on top of one or more intermediate layers. In addition, before the design can be drawn and the pigments applied to the final layer of plaster, a whole series of prepatory operations must be carried out: snapping the cords (establishing a centre line or a grid by means of a taut cord dipped in paint and snapped against the surface), applying the rough plaster undercoat or arriccio, incising lines, drawing the design with sinopia red. It is thus clear how unreliable it can be to calculate the time taken to execute a fresco simply from the number of giornate -- especially if we do not know how many workers were involved. To get a comprehensive idea of the time needed to produce a fresco, you have also to take into account all the preliminary work, which in the fourteenth century included the preparation of much of the materials and of drawings to be transferred to the wall. Even if we consider only the application of the water-based pigments on the freshly laid plaster, all that can confidently be said is that it is possible to paint more than a single giornata in one day, if small areas of plaster are used, but that it is not usually possible to paint less than one giornata , because of the risk of imperfect carbonation of the area painted later.

Giornata analyzed in The Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple:

|

|

|

Giornata analyzed in The Nativity:

|

|

|

Fresco Cycle:

The fresco cycle presents a narrative of the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ. The prominence of the story of the Virgin is appropriate considering the dedication of the Chapel to the Virgin. The more specific dedication to the Virgin of the Annunciation helps to explain the prominent positioning of the Annunciation on the Chancel Arch leading to the altar of the Chapel. This scene also marks the break from the Life of the Virgin to the Life of Christ.

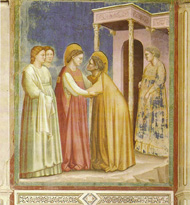

The narrative begins on the upper level of the south wall with the Story of Joachim and Anna, the parents of the Virgin. The story moves from east to west beginning with the Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple and ending with Joachim and Anna meeting at the Golden Gate.

The Story of the Virgin begins on the upper register of the north wall with scenes moving from west to east of the Birth of the Virgin through to the Marriage of the Virgin.

The Incarnation and Infancy of Christ begins on the Chancel Arch with the Annunciation and Visitation and is then continued on middle register of the south wall with scenes of the Nativity to the Sacrifice of the Innocents.

The middle register of the North wall focuses on scenes pertaining to the Ministry of Christ, beginning with Christ among the Elders and ending with the Expulsion of the Money Changers from the Temple.

The most extensive narrative is dedicated to scenes of the Passion, Resurrection, Ascension, and Pentecost. The Passion cycle begins on the Chancel Arch with the Pact of Judas, and then continues in sequence from the bottom register of the South Wall through the bottom register of the North Wall.

Giotto as Storyteller:

Giotto's success as a storyteller is manifest in his ability to transform the formulas of conventional religious images and make them appear physically and emotionally present to the viewer. This can be seen by comparing the Betrayal of Christ from the Arena Chapel to the same scene on the apron of a thirteenth century Crucifix:

|

|

|

While corresponding in many details, including the kiss of Judas and St. Peter's rash response of cutting off the ear of Malchus the servant of the high priest, these images are clearly worlds apart. Giotto has transformed the weightless, puppet-like figures of the earlier work into truely monumental figures who appear to convincingly occupy space. Perhaps even more significantly Giotto has added an emotional depth to the scene. At the center is the face to face confrontation of Judas and Christ. Judas's sinister and animalistic embrace is met with an all-knowing expression of absolute forgiveness:

Christ's acceptance of the Betrayal is opposed to Peter's violent attack of Malchus:

Giotto brings out the emotional response of the high priest whose harsh vengeance is suddenly checked by his sudden realization of Christ's true nature:

Giotto's ability to render this psychological drama in the detail of the hand anticipates an artistic tradition that will lead to juxtaposed hands of Adam and God in Michelangelo's Creation of Adam from the Sistine Ceiling.

|

|

|

The Lamentation on the left is also from the same twelfth century Crucifix. Compare it to Giotto's representation of the same subject matter.

Giotto's accomplishment of making the story of Christ physically and emotionally present is directly connected to a popular trend in religious piety of the early-fourteenth century to break down the barriers between religious and everyday experience. This trend is manifest in the Franciscan devotional text entitled The Meditations on the Life of Christ. Throughout this text attributed to the Pseudo-Bonaventura emphasis is placed on Christ's human nature, and the author frequently appeals to the readers immediate experience to make the Biblical narrative directly present. This is brought out in the following excerpt from the account of the Betrayal of Christ:

"Even as He spoke, that wicked man, Judas, most evil merchant, came before the others and kissed Him. It is said to have been the custom of the Lord Jesus to receive disciples He had sent out with a kiss on their return. Therefore the traitor gave the kiss as the sign. Preceding the others, he returned with a kiss, almost as though to say, 'I have not come with these soldiers but, returning, I kiss you according to custom and say '"Ave Rabbi, God save You, Master." ' O real traitor! Pay careful attention and follow the Lord as He patiently and benignly receives the treacherous embraces and kisses of that wretch whose feet He had washed but a short time before and to whom He had given the supreme food. How patiently He allows Himself to be captured, tied, beaten, and furiously driven, as though He were an evil-doer and indeed powerless to defend Himself! How He even pities His fleeing and errant disciples! And see also their grief as, unnerved, sorrowfully weeping and lamenting like orphans, and frightened by fear, they leave; and their sorrow grows greater as they see their Lord so miserably led away...."

While the layout of the cycle clearly asks us to follow the narrative sequence, it is also evident that Giotto was very much aware of the relationships of adjacent images and the development of particular themes in the fresco cycle. Note for example the contrast between the reactions of Christ in the adjacent scenes on the south wall of the Presentation of the Infant Christ into the Temple and the Betrayal of Christ directly below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Similarly, again on the South Wall, compare the stacked images of the Sacrifice of the Innocents to the Mocking of Christ:

|

|

|

|

Comparably on the North Wall note the juxtaposition of the stacked images of the Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple and the Descent of the Holy Spirit:

|

|

|

|

On the Chancel Arch, the Pact of Judas is juxtaposed to the Visitation:

|

|

|

Note how Giotto develops particular themes in the cycle. The theme of expulsion and acceptance is interwoven throughout the cycle. For example, the Story of Joachim and Anna is bracketed on the South Wall with the Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple and the poignant image of Joachim and Anna meeting at the Golden Gate:

|

|

|

This theme of Expulsion and Acceptance takes on further significance when it is remembered that one of the harshest forms of punishment in fourteenth-century Italy was to banish someone from their town. One's identity was tied up in one's membership in a particular community. To be banished, therefore, had the significance of losing one's identity. Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet (Act III, scene 3) illustrates this when he has Romeo say upon hearing of his banishment from Verona:

"Ha, banishment? Be merciful, say 'death'; For exile hath more terror in his look, Much more than death. Do not say 'banishment?'"

Giotto's power as a storyteller can be seen in the juxtaposition of particular details. Most especially, compare Giotto's representations of kisses. Contrast for example, the kiss of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate to that of Judas and Christ in the Betrayal:

|

|

|

South Wall

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

East Wall

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

West Wall:

|

|

North Wall:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Select Sources:

Basile, Giuseppe. Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, London, 1993.

Cole, Bruce, Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, New York, 1993.

Stubblebine, James (ed.), Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, New York, 1969.