Art

web | ARTH Home | ARTH

Courses | ARTH 109 | ARTH 109 Assignments | Forward | Back

| Contact

Arth 109

Early Classical Sculpture

Slide List 8

|

|

| Metropolitan Kouros, Early Archaic, c.

615-590 B.C. |

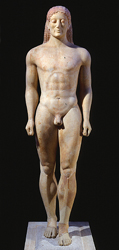

Kroisos (Kouros from Anavysos), c. 540-515

B.C. |

|

|

|

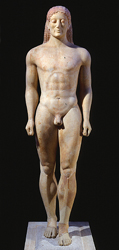

| Kritios Boy, from the Acropolis of Athens,

c. 480 B.C. 360 degree view of the Kritios Boy. |

|

Reconstruction of tbe Temple of Aphaia at Aegina.

|

Reconstruction of the pediment of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina.

|

|

|

|

| Archer from the East Pediment of the Temple

of Aphaia at Aegina, c. 490-480 B.C. |

Archer from the west pediment of the Temple

of Aphaia at Aegina, c. 510 B.C. |

|

|

| Fallen Warrior from the East Pediment of

the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, c. 490-480 B.C. |

Fallen Warrior from the West Pediment of

the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, c. 510 B.C. |

|

|

| Polykleitos, Doryphoros, original c. 450-440

B.C., Roman copy. 360 degree view of the Doryphoros. |

|

| |

|

| |

Warrior from Riace, bronze, third quarter

of the 5th c. B.C. |

Term

Contrapposto- placed opposite. The disposition of the parts

of the body so that they turn along oblique axes around a central

vertical axis. The figure is "counterpoised" so that

the weight-bearing leg, or engaged leg, is distinguished from

the raised, or free leg, the resulting shift in the axes of hips

and shoulders is observed. Above all, the stiff frontality and

parallel alignments which are characteristic of Egyptian and Archaic

Greek sculpture are avoided, and the body is conceived of as an

organic mechanism composed of interdependent parts. Note

how in a work like the Kritios Boy the artist goes beyond the

observation of the shifting axes in the body to record the distinction

between tensed and relaxed muscles.

Question for Review

|

|

| Anavysos Kouros, c. 540-515 B.C. |

Kritios Boy, c. 480 B.C. |

Define the transformations that have taken place between the

sculpture of the late archaic period and that of the early Classical

period. Note how these imply a change in relationship of the viewer

to the work of art.

Quotation

In commenting upon the opinion of the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus

that health in the body is the result of the harmony of all its

constituent elements, the physician Galen (second century A.D.)

adds:

"Beauty resides not in the commensurability, but in the

commensurability of the parts, such as finger to finger, and of

all the fingers to the metacarpus and the wrist, and of these

to the forearm, and of the forearm to the arm, in fact of everything

to everything, as it is written in the Canon of Polykleitos.

For having taught us in that treatise all the symmetriae of the

body, Polykleitos supported this treatise with a work, having

made a statue of a man according to the tenets of his treatise,

and having called the statue itself, like the treatise, the Canon.

Art

web | ARTH

Home | ARTH Courses | ARTH 109 | ARTH

109 Assignments | Forward | Back | Contact