|

p. 83: Oil paintings often depict things. Things which in reality are buyable. To have a thing painted and put on canvas is not unlike buying it and putting it in your house. If you buy a painting you buy also the look of the thing it represents.

The analogy between possessing and the way of seeing which incorporated in oil painting, is a factor usually ignored by art experts and historians. Significantly enough it is an anthropologist who has come closest to recognizing it. /p. 84

Lévi-Strauss writes:

| It is this avid and ambitious desire to take possession of the object for the benefit of the owner or even of the spectator which seems to me to constitute one of the outstandingly original features of the art of Western civilization. |

If this is true--though the historical spac of Lévi-Strauss's generalization may be too large-- the tendency reached its peak during the period of the traditional oil painting.

The term oil painting refers to more than technique. It defines an art form. The technique of mixing pigment with oil has existed since the ancient world. But the oil painting as an art form was not born until there was a need to develop and perfect this technique (which soon involved using canvas instead of wooden panels) in order to express a particular view of life for which the techniques of tempera or fresco were inadequate. When oil painting was first used --at the beginning of the fifteenth century in Northern Europe -- for painting pictures of a new character, this character was somewhat inhibited by the survival of various medieval artistic conventions. The oil painting did not fully establish its own norms, its own way of seeing until the sixteenth century.

Nor can the end of the period of the oil painting be dated exactly. Oil paintings are still being painted today. Yet the basis of its traditional way of seeing was undermined by Impressionism and overthrown by Cubism. At about the same time the photograph took the place of the oil painting as the principal source of visual imagery. For these reasons the period of the traditional oil painting may be roughly set as between 1500 and 1900.

The tradition, however, still forms many of our cultural assumptions. It defines what we mean by pictorial likeness. Its norms still affect the way we see such subjects as landscape, women, food, dignitaries, mythology. It supplies us with our archetypes of 'artistic genius'. And the history of the tradition, as it is usually taught, teaches us that art prospers if enough individuals in society have a love of art.

What is love of art? /p. 85

Let us consider a painting which belongs to the tradition whose subject is an art lover.

|

What does it show?

The sort of man in the seventeenth century for whom painters painted their paintings.

What are these paintings?

Before they are anything else, they are themselves objects which can be bought and owned. Unique objects. A patron cannot be surrounded by music or poems in the same way as he is surrounded by his pictures.

It is as though the collector lives in a house built of paintings. What is their advantage over walls of stone or wood?

They show him sights: sights of what he may possess. /p. 86

Again, Lévi-Strauss comments on how a collection of paintings can confirm the pride and amour-propre of the collector.

| For Renaissance artists, painting was perhaps an instrument of knowledge but it was also an instrument of possession, and we must not forget, when we are dealing with Renaissance painting, that it was only possible because of the immense fortunes which were being amassed in Florence and elsewhere, and that rich Italian merchants looked upon painters as agents, who allowed them to confirm their possession of all that was beautiful and desirable in the world. The pictures in a Florentine palace represented a kind of microcosm in which the proprietor, thanks to his artists, had recreated within easy reach and in as real a form as possible, all those features of the world to which he was attached. |

The art of any period tends to serve the ideological interests of the ruling class. If we were simply saying that European art between 1500 and 1900 seerved the interests of successive ruling classes, all of whom depended in different ways on the new power of capital, we should not be saying anything very new. What is being /p. 87 proposed is a little more precise; that a way of seeing the world, which was ultimately determined by new attitudes to property and exchange, found its visual expression in the oil painting, and could not have found it in any other visual art form.

Oil painting did to appearances what capital did to social relations. It reduced everything to the equality of objects. Everything became exchangeable because everything became a comodity. All reality was mechanically measured by its materiality. The soul, thanks to the Cartesian system, was saved in a category apart. A painting could speak to the soul --by way of what it referred to, but never by the way it envisaged. Oil painting conveyed a vision of total exteriority.

Pictures immediately spring to mind to contradict this assertion. Works by Rembrandt, El Greco, Giorgione, Vermeer, Turner, etc. Yet if one studies these works in relation to the tradition as a whole, one discovers that they were exceptions of a very special kind.

The tradition consisted of many hundreds of thousands of canvases and easel pictures distributed throughout Europe. A great number have not survived. Of those which have survived only a small fraction are seriously /p. 88 as works of fine art, and of this fraction another small fraction comprises the actual pictures repeatedly reproduced and presented as the works of 'the masters'.

Visitors to art museums are often overwhelmed by the number of works on display, and by what they take to be their own culpable inability to concentrate on more than a few of these works. In fact such a reaction is altogether reasonable. Art history has totally failed to come to terms with the problem of the relationship between the outstanding work and the average work of the European tradition. The notion of Genius is not in itself an adequate answer. Consequently the confusion remains on the wall of the galleries. Third-rate works surround an outstanding work without recognition --let alone explanation-- of what fundamentally differentiates them.

The art of any culture will show a wide differential of talent. But in no other culture is the difference between 'masterpiece' and average work so large as in the tradition of the oil painting. In this tradition the difference is not just a question of skill or imagination, but also of morale. The average work --an increasingly after the seventeenth century-- was a work produced more or less cynically: that is to say the values it was nominally expressing were less meaningful to the painter than the finishing of the commission or the selling of his product. Hack work is not the result of either clumsiness or provincialism; it is the result of the market making more insistent demands than the art. The period of the oil painting corresponds with the rise of the open art market. And it is in this contradiction between art and market that the explanations must be sought for what amounts to the contrast, the antagonism existing between the exceptional work and the average.

Whilst acknowledging the existence of the exceptional works, to which we shall return later, let us first look broadly at the tradition.

What distinguishes oil painting from any other form of painting is its special ability to render the tangibility, the texture, the lustre, the solidity of what it depicts. It defines the real as that which you can put your hands on./ p. 89 Although its painted images are two-dimensional, its potential of illusionism is far greater than that of sculpture, for it can suggest objects possessing colour, texture, and temperature, filling a space and, by implication, filling the entire world.

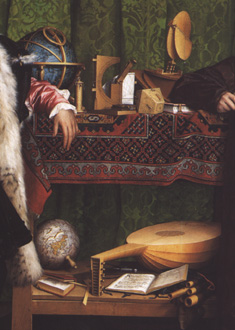

Holbein's painting of The Ambassadors (1533) stands at the beginning of the tradition and, as often happens with a work at the opening of a new period, its character is undisguised. The way it is painted shows what it is about. How is it painted?

It is painted with great skill to create the illusion in the spectator that he is looking at real objects and materials. We pointed out in the first essay that the sense of touch was like a restricted, static sense of sight. Every square inch of the surface of this painting, whilts remaining purely visual, appeals to, importunes, the sense of touch. The eye moves from fur to silk to metal to wood to velvet to marble to paper to felt, and each time what the eye perceives is already translated, within the painting itself, into the language of tactile sensation. The two men have a certain presence and ther are many objects which symbolize ideas, but it is the materials, the stuff, by which the men are surrounded and clothed which dominate the painting.

Except for the faces and hands, there is not surface in this picture which does not make one aware of how it has been elaborately worked over --by weavers, embroiderers, carpet-makers, goldsmiths, leather workers, mosaic-makers, furriers, tailors, jewellers-- and of how this working-over and the resulting richness of each surface has been finally worked-over and reproduced by Holbein the painter.

This emphasis and the skill that lay behind it was to remain a constant of the tradition of oil painting.

Works of art in earlier traditions celebrated wealth. But wealth was then a symbol of a fixed social or divine order. Oil painting celebrated a new kind of wealth -- which was dynamic and which found its only sanction in the supreme buying power of money. Thus painting itself had to be able to demonstrate the desirability of what money could buy. And the visual desirability of what can be bought lies in its tangibility, in how it will reward the touch, the hand, of the owner.

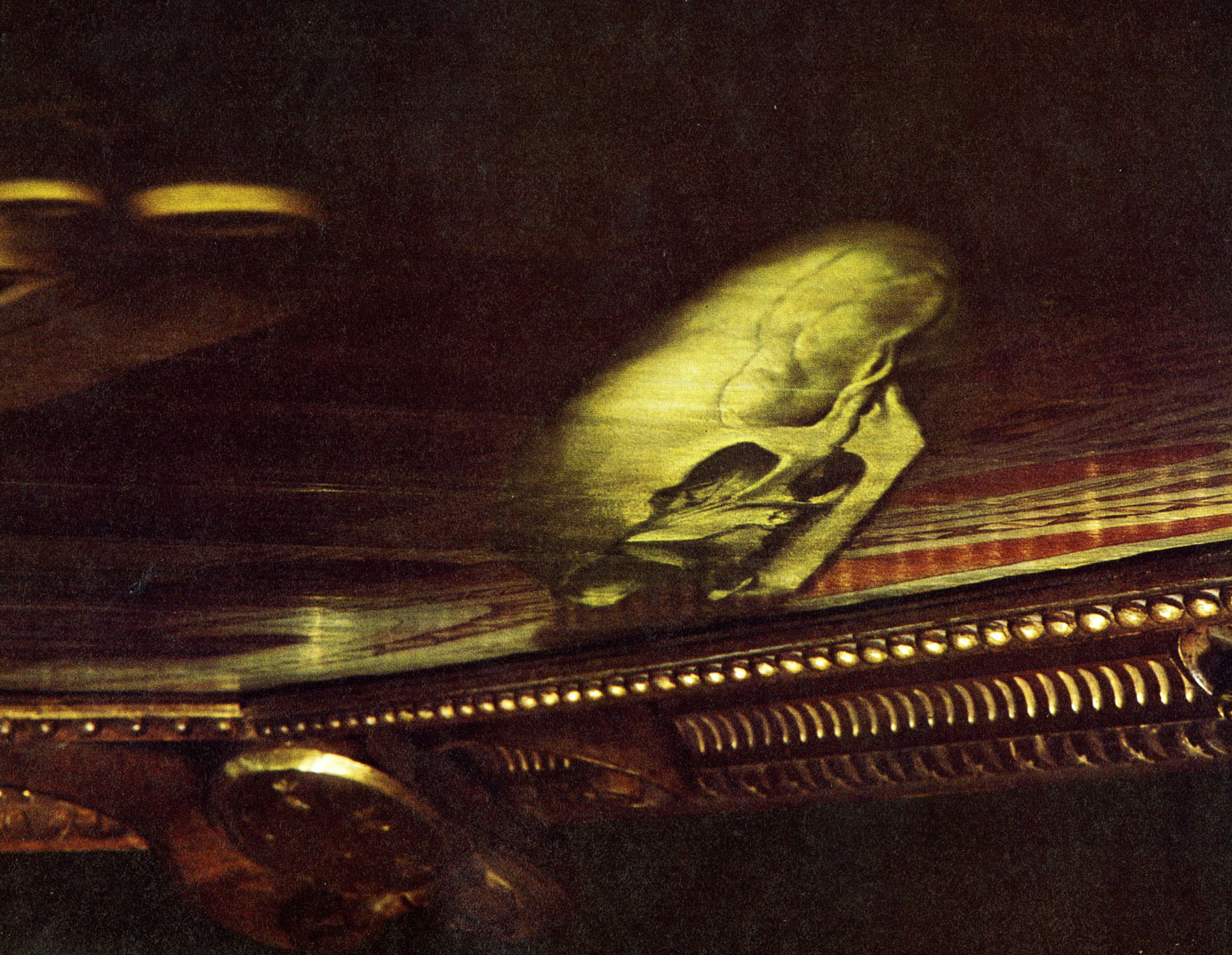

In the foreground of Holbein's Ambassadors there is a mysterious, slanting, oval form. This represents a highly distorted skull...

There are several theories about how it was painted and why the ambassadors wanted it put there. But all agree that it was a kind of momento mori: a play on the medieval idea of using the skull as a continual reminder of the presence of death. What is significant for our argument is that the skull is painted in a (literally) quite different optic from everything else in the picture. If the skull had been painted like the rest, the metaphysical implication would have disappeared; it would have become an object like everything else, a mere part of a mere skeleton of a man who happened to be dead....

/p. 94: Let us now return to the two ambassadors, to their presence as men. This will mean reading the painting differently: not at the level of what it shows within its frame, but at the level of what it refers outside it.

The two men are confident and formal; as between each other they are relaxed. But how do they look at the painter --or at us? There is their gaze and their stance a curious lack of expectation of any recognition. It is as though in principle their worth cannot be recognized by others. They look as though they are looking at something of which they are not part. At something which surrounds them but from which they wish to exclude themselves. At the best it may be a crowd honouring them; at the worst, intruders.

What were the relations of such men with the rest of the world?

The painted objects on the shelves between them were intended to supply --to the few who could read the allusions-- a certain amount of information about their position in the world. For centuries later we can interpret this information according to our own perspective.

The scientific instruments on the top shelf were for navigation. This was the time when the ocean trade routes were being opened up for the slave trade and for the traffic which was to siphon the riches from other continents into Europe, and later supply the capital for the take-off of the Industrial Revolution.

In 1519 Magellan had set out, with the backing of Charles V, to sail round the world. He and an astronomer friend, with whom he planned the voyage, arranged with the Spanish court that they personally were to keep twenty per cent of the profits made, and the right to run the government of any land they conquered.

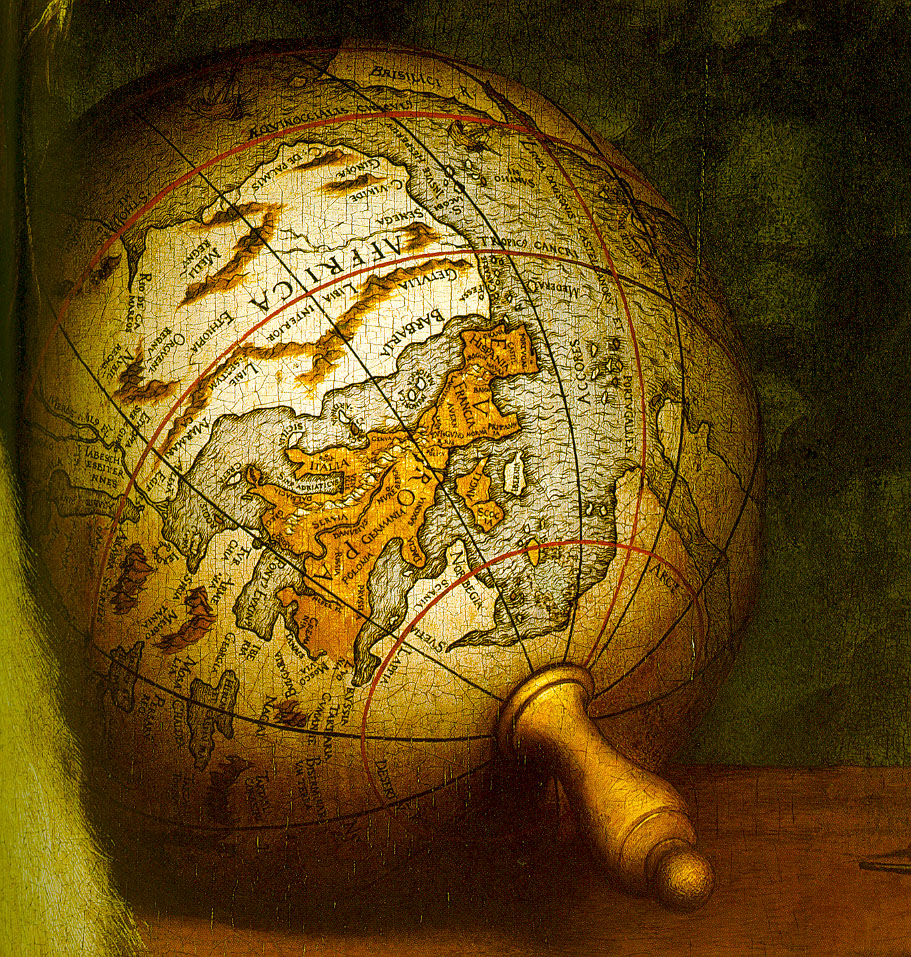

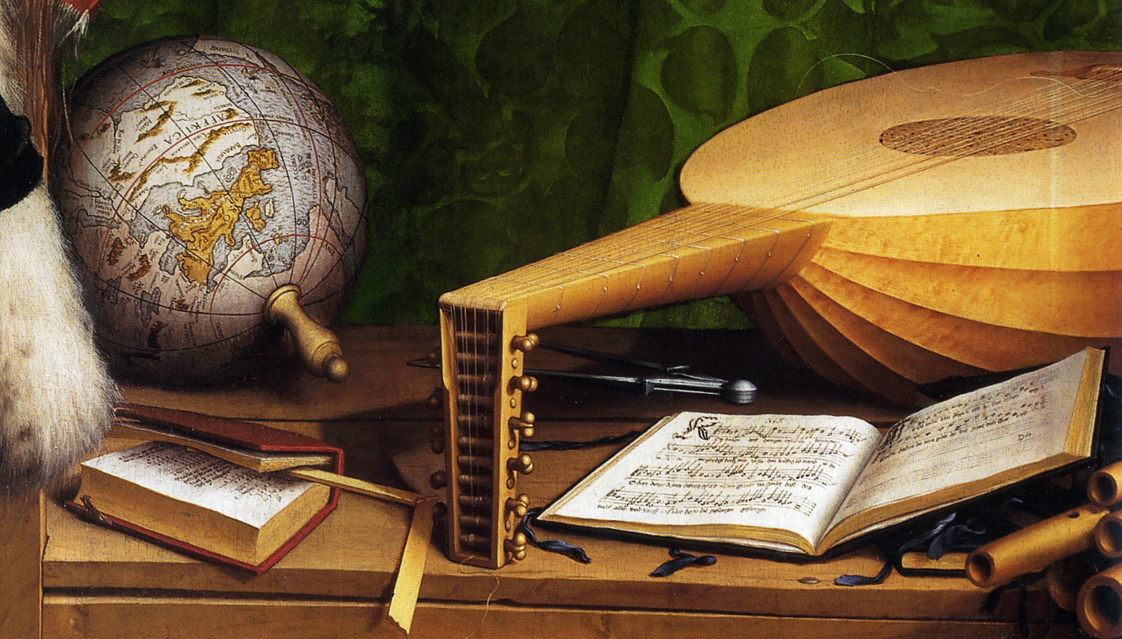

The globe on the bottom shelf is a new one which charts this recent voyage of Magellan's. Holbein has added to the globe the name of the estate in France which belonged to the ambassador on the left.

[On the lower shelf] beside the globe are a book of arithmetic, a hymn book, and a lute. To colonize a land it was necessary to convert its people to Christianity and accounting, and thus to prove to them that European civilization was the most advanced in the world. Its art included....

/p. 96: How directly or not the two ambassadors were involved in the first colonizing ventures is not particularly important, for what we are concerned with here is a stance towards the world; and this was general to a whole class. The two ambassadors belonged to a class who were convinced that the world was there to furnish their residence in it. In its extreme form this conviction was confirmed by the relations being set up between colonial conqueror and the colonized.

These relations between conqueror and colonized tended to be self-perpetuating. The sight of the other confirmed each in his inhuman estimate of himself. ...The way in which each sees the other confirms his own view of himself.

/p. 97: The gaze of the ambassadors is both aloof and wary. They expect no reciprocity. They wish the image of their presence to impress others with their vigilance and their distance. The presence of kings and emperors had once impressed in a similar way, but their images had been comparatively impersonal. What is new and disconcerting here is the individualized presence which needs to suggest distance. Individualism finally posits equality. Yet equality must be made inconceivable.